17 May Painting the Parks

Art is the child of Nature.

— Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

THE ARTS AND OUR NATIONAL PARKS have always mixed beautifully in our civil heritage. Well before conservationist Stephen T. Mather, the founder and first director of the National Park Service (NPS), was appointed in 1917, others were crying out for the wilderness. At the easel, the escritoire and behind early cameras, 19th-century artists sought and saw the splendor of wild places. They brought America’s wilderness into the public view and helped establish conservation as a national value.

The concept of a national park system is generally attributed to George Catlin [1796–1872], the Pennsylvania-born artist regarded for his paintings of Native Americans, according to the NPS. Catlin was traveling in the Dakota Territory in 1832 and lamented that the country’s westward expansion was having a dramatic impact on the people and the land. He envisioned “some great protecting policy of government … in a magnificent park … a nation’s park, containing man and beast, in all the wild[ness] and freshness of their nature’s beauty!”

Catlin’s vision was partly realized more than 30 years later with the Yosemite Grant Act, signed by President Abraham Lincoln in 1864. It established the “cleft” in the granite peak of the Sierra Nevada Mountains for public use, “inalienable for all time.”

By the late 1860s, a small band of early environmentalists founded the Free Niagara movement, which held that the natural beauty of the land surrounding the falls should be protected from commercial interests and exploitation and remain free to the public. The leader of the movement was America’s first landscape architect, Frederick Law Olmsted, perhaps best known for designing New York City’s Central Park. His leadership helped establish Niagara Falls as a state park in 1885.

Preserved in a Painterly Light

The romantic portrayals of nature by writers, including James Fenimore Cooper [1789–1851] and Henry David Thoreau [1817–1862], and painters, including Thomas Cole [1801 –1848] and Frederic Edwin Church [1826–1900], began to compete with the prevailing notion that wilderness was something to tame, according to The National Park Service: A Brief History, written by Barry Mackintosh. Serious consideration for the preservation of such places gained traction.

Integral in generating publicity for open spaces was the Hudson River School, an influential group of artists on the East Coast formed under the influence of Cole during the mid-19th century. The movement painted the landscape in a romantic light, depicting a reverence for nature’s beauty. Later generations of painters carried the style to the Rocky Mountains. Among them were Albert Bierstadt [1830–1902] and Thomas Moran [1837–1926], who joined government expeditions to explore and document territory that would otherwise be inaccessible.

In 1871, Moran explored the area that would become the nation’s first national park the following year. He spent 40 days in the region, documenting more than 30 sites with the Hayden Geological Survey. Moran’s sketches — along with photographs by William Henry Jackson [1843–1942] — inspired Congress to establish Yellowstone National Park in 1872. The relationships also benefited the artist, whose first large financial success resulted from this connection. He began signing his paintings with “T-Y-M,” for Thomas “Yellowstone” Moran.

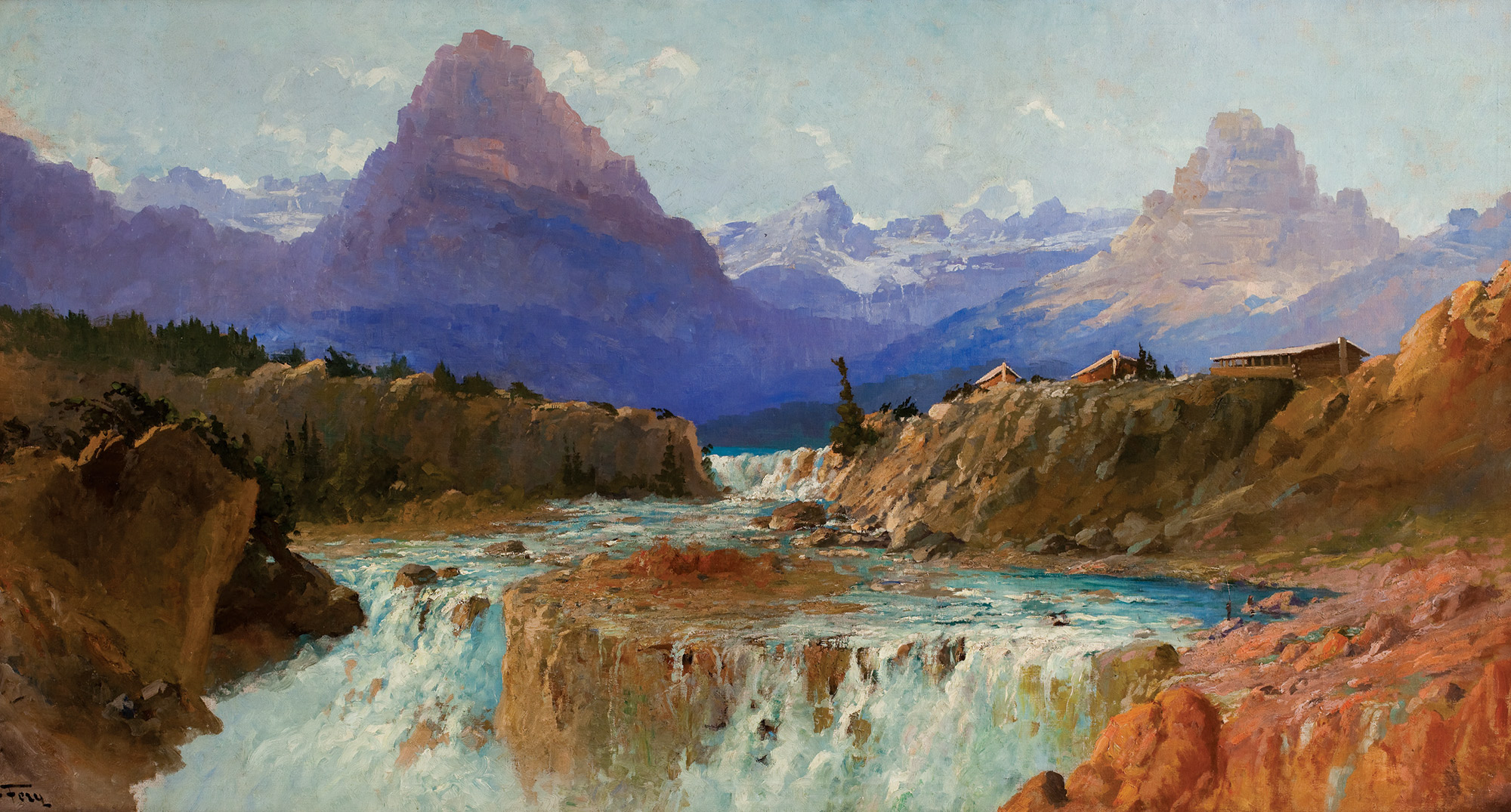

The parks were also visible on a commercial scale. In 1911, the Great Northern Railroad commissioned artist John Fery [1859–1934] to paint Glacier National Park in Montana. His paintings served as travel advertisements throughout the North, found on the walls of train depots, hotels, ships, travel agencies, colleges and other institutions.

“The train stations were the airports of their time, and artists such as Fery were cheerleaders of the parks to travelers who hoped to see them or were on their way already to experience them,” says Larry Len Peterson, author of John Fery: Artist of Glacier National Park & The American West. “There were few Americans who, in their lifetime, did not see his work in person. It was unavoidable and irresistible.”

Artist in Residence: Picturing the Parks for Future Generations

More than a century ago, artists put in motion a legacy of conservation and creativity. Today, contemporary artists continue this tradition, contributing to the vitality of one of the country’s most valuable assets with the help of Artist in Residence programs. Whether staying in a remote cabin in Alaska’s Denali National Park or contemplating early Southwest history at Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado, these programs provide artists of all mediums with the opportunity to create in varied natural and cultural settings.

“Artists helped make the parks possible a generation before the NPS was established — 100 years ago this August,” Jonathan B. Jarvis, director of the NPS, says. “Our hope is to continue to inspire a new generation of artists in various media to explore the meaning and majesty of the national parks during this centennial year and extending into the next hundred years.”

The National Parks Arts Foundation oversees the programs that differ in each park, but usually run from one to three months and offer lodging. “I’ve always felt that art shouldn’t be stuck in museums and galleries, behind some velvet rope. It needs to be everywhere. And it can be,” says Tanya Ortega, founder and president of the foundation. “We’ve set up these residencies in these specific parks because we believe that this will draw the highest level of artist, regardless of the market, both known and unknown.”

K. Gretchen Greene, a Boston-area sculptor, participated in Glacier National Park’s 2015 residence program. “My work, while mostly abstract, is inspired by moments in nature, usually near water,” Greene says. “I was interested in spending a block of time in a beautiful natural setting deliberately collecting memories to incorporate into my work.”

While in Glacier, Greene kayaked Lake McDonald and slept on its shores. Despite the calm of the lake, she found that it was the waterfalls and river rapids, with their swirling, roiling energy, that drew her in. She says she wanted to create sculptures that imparted the experience of the park for viewers far away.

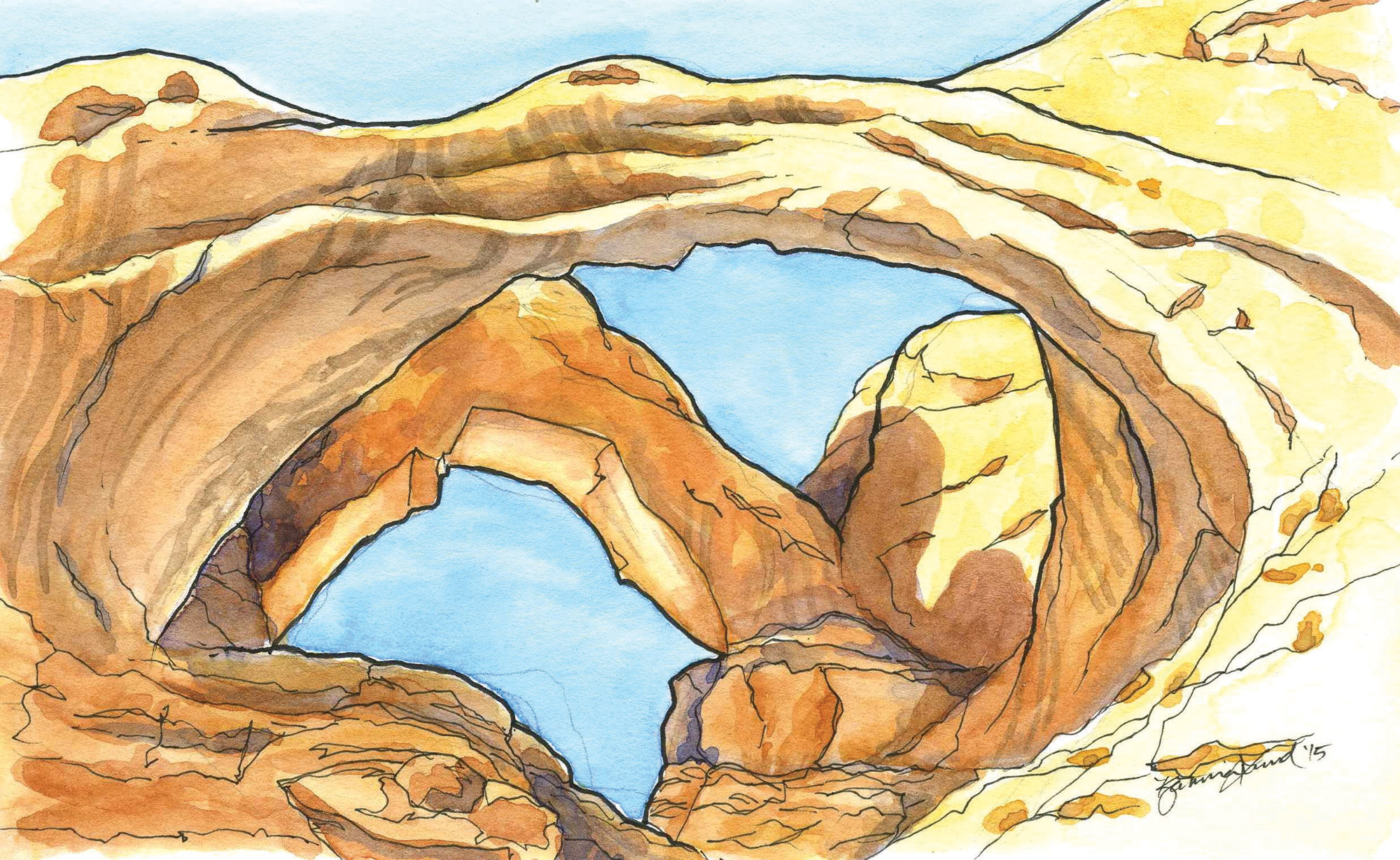

A related program in Southeast Utah, the Community Artist in the Parks, provides a similar experience without the residency requirement. Last year, painter Katrina Lund participated in the program for seven months, logging more than 400 hours in the landscape. She focused on plein air sketching and hosted monthly “sketch crawls” with the public in three or four locations daily.

“I loved meeting people who would tell me they weren’t artists, that they weren’t any good at art or don’t have a creative bone in their body, yet they would sit down and sketch and realize they could connect in a completely different way,” Lund says.

Giving Back in Plein Air

Artists hold regular exhibitions and paint-outs at national parks and state monuments throughout the country. The sales from many of these events support art programs in the nation’s parks.

This July, Grand Teton National Park will host more than 40 artists in the park and in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. “Because the artists have 10 days to paint, they really get a chance to explore the entirety of the park and Jackson Hole, and this results in a lot of paintings that move beyond the well-known landmarks,” says Stephen C. Datz, president of Rocky Mountain Plein Air Painters.

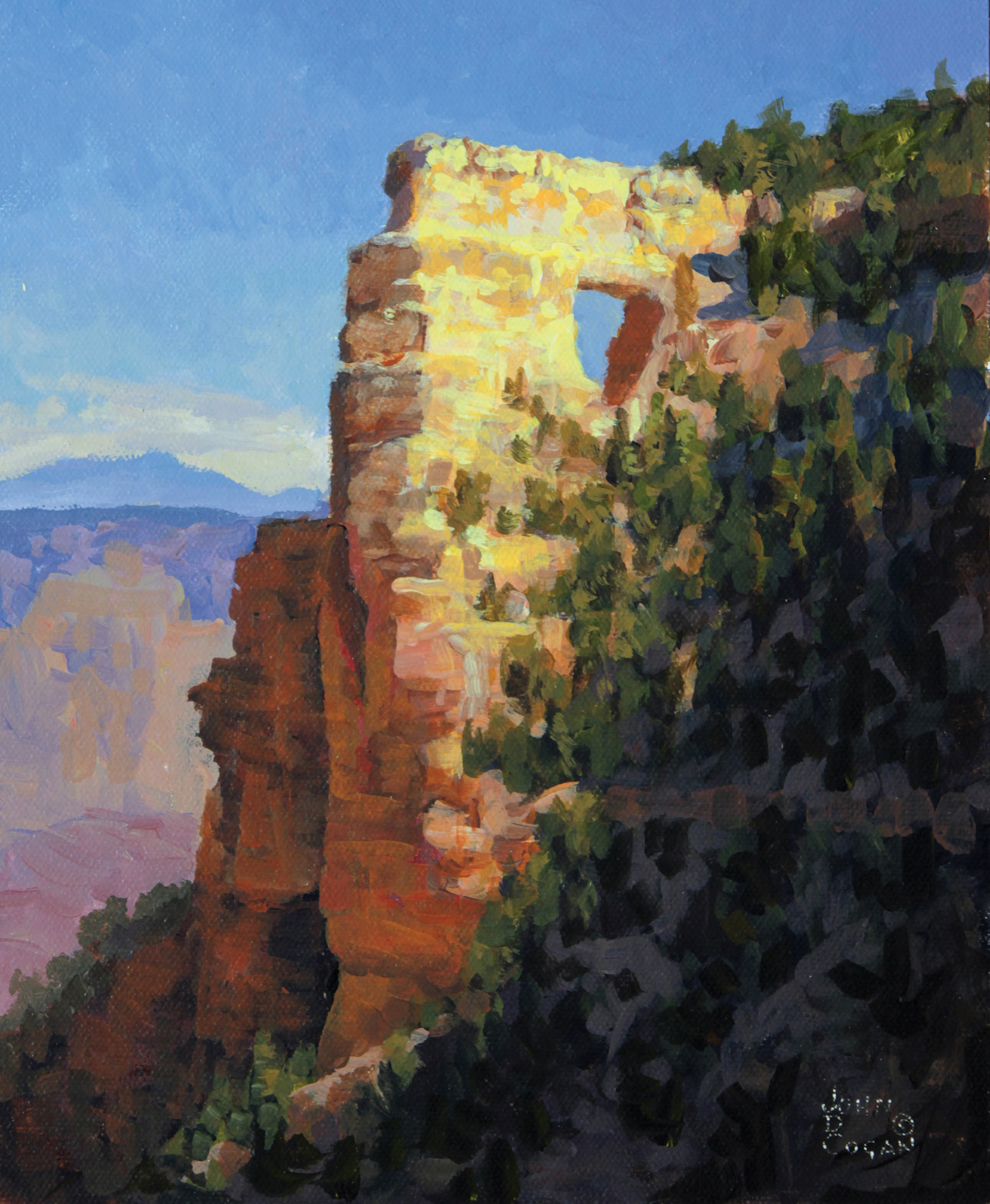

Soon after, the Grand Canyon Celebration of Art will take place in the fall in Arizona. In honor of the NPS centennial, artists can submit work from any national park to be sold in addition to a plein air piece they create in the Grand Canyon. Work will be displayed at the historic Kolb Studio located at the South Rim, the historic photography studio operated by brothers Emery and Ellsworth Kolb for 75 years. Proceeds from the event will help fund a permanent art venue there.

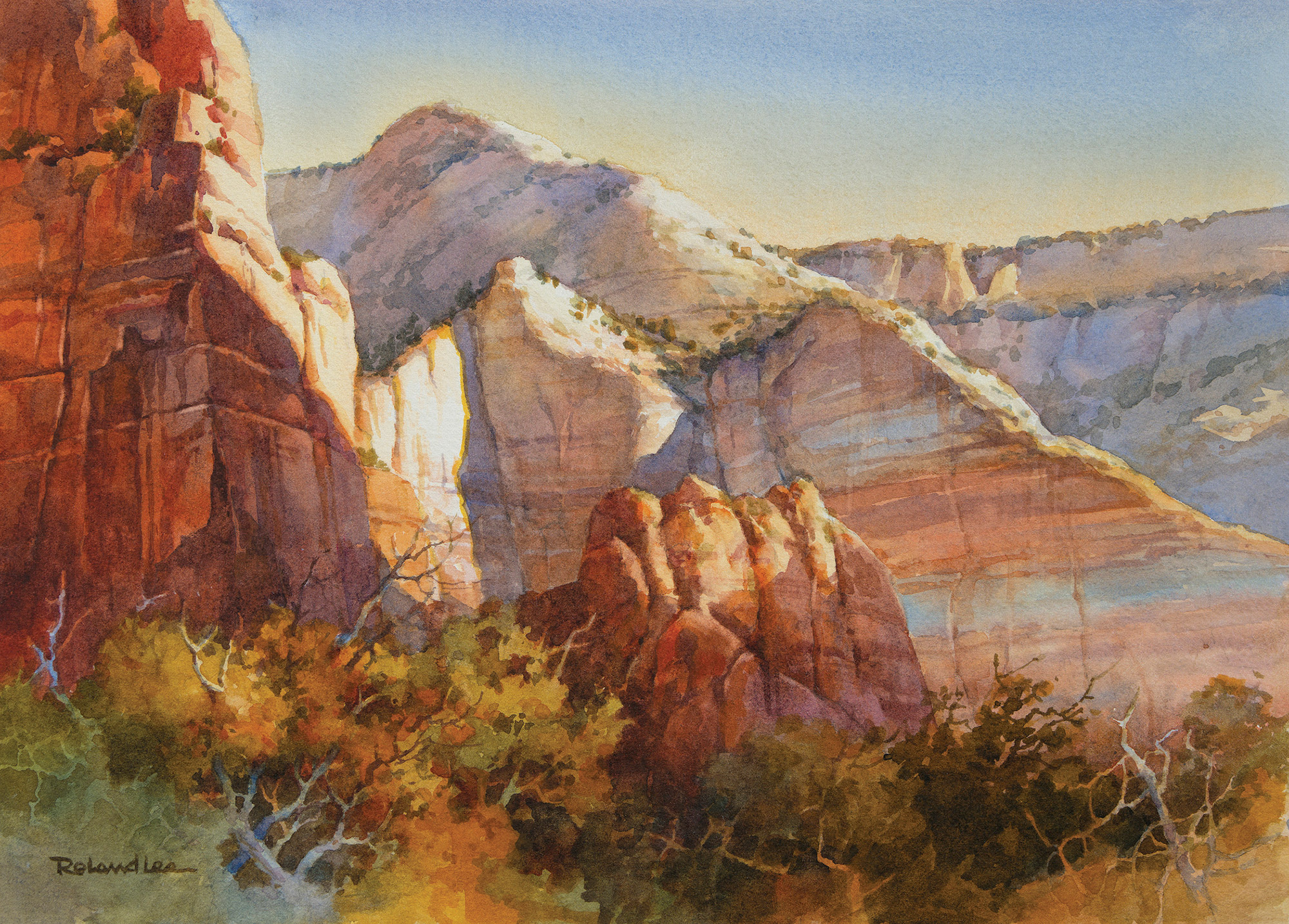

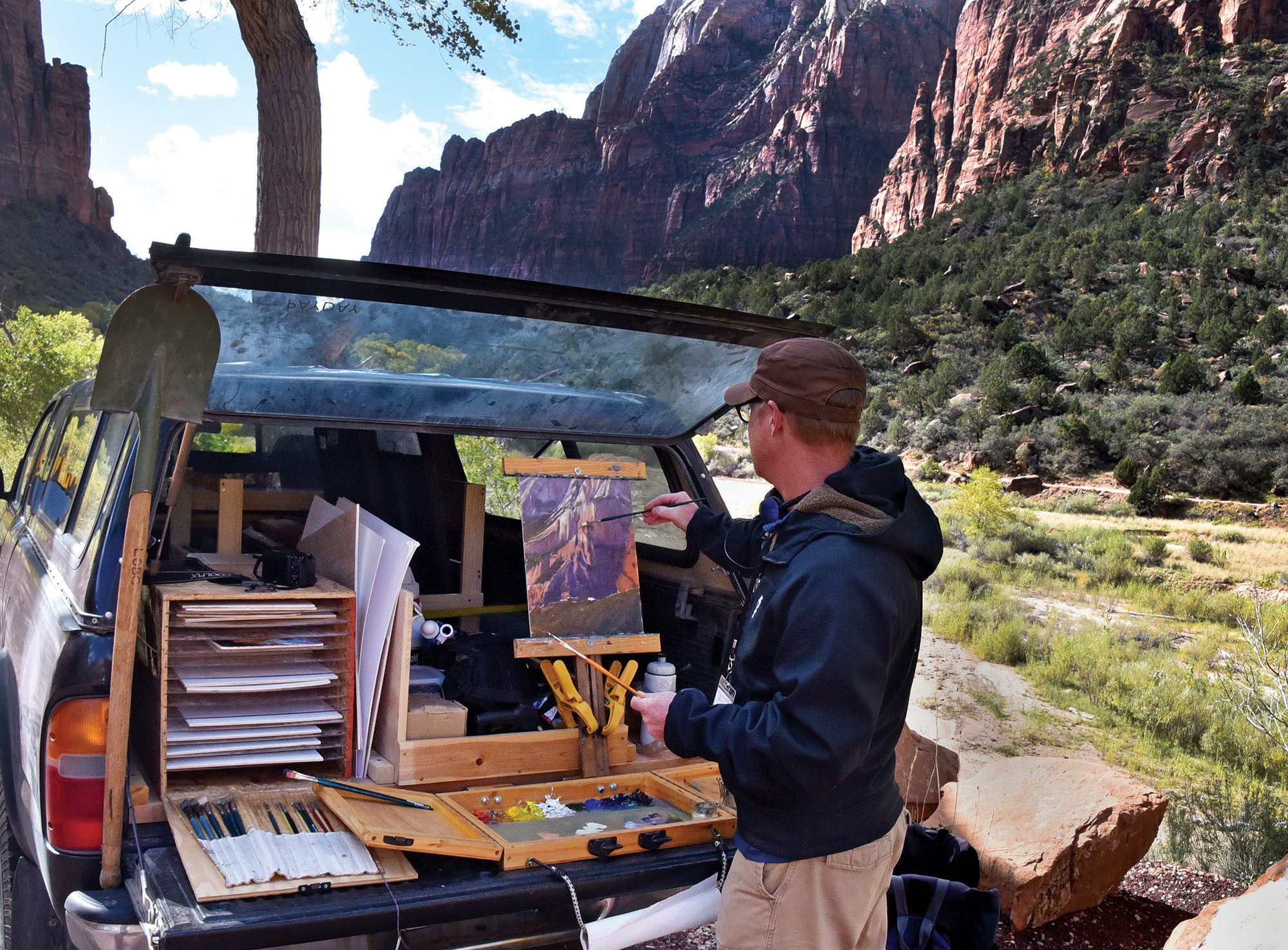

Also taking place this fall is Zion’s Plein Air Invitational. During the weeklong event, 24 artists paint throughout the park. Visitors can observe and chat with the artists, attend one-hour painting demonstrations during the week, listen to lectures at Zion Lodge, and purchase works at the concluding auction and art sale. Proceeds support educational programs in Zion.

Artist Roland Lee has visited Zion since he was a teenager. “As an artist, it has been not only my playground but also my art studio for over 40 years. The soaring peaks and the winding canyons captivate my spirit and continue to be a source of inspiration for my paintings today,” he says. “As I reflect on the current celebration of 100 years of our national parks, I am grateful for the early artists who helped make our nation aware of the need to protect certain special places. Through their insight, and the efforts of many since, these lands will continue to bless future generations.”

- Thomas Moran [1837–1926], “Golden Gate” | Courtesy: NPS, Yellowstone National Park

- John Fery [1859–1934], “Zion National Park” | Oil on Board | Collection of Mike & Lisa Overby

- Roland Lee, “Joy in the Morning” | Transparent Watercolor | Lee will participate in Zion’s plein air event November 7 through 12.

- Carol Swinney, “Cathedral Symphony” | Oil | Photo: Jack Kulawik Photographer | Swinney is a member of the Rocky Mountain Plein Air Painters who will host a fine art show for Grand Teton National Park July 13 to 17.

- Katrina Lund, “Double Arch” | Participant in Utah’s Community Artist in the Parks

- Zion National Park plein air painter Hadley Rampton. Photos: Daren Reehl

- Zion National Park plein air painter Richard Lindenberg. Photos: Daren Reehl

- Julia Seelos also painting in Zion. Photos: Daren Reehl

- John D. Cogan, “Summer Afternoon Angels” | Acrylic | Cogan has participated in the Grand Canyon’s plein air event for eight years and Zion’s for seven.

- Zion National Park plein air painter John Lintott. Photos: Daren Reehl

No Comments