04 Jul Fire and Story: The Rise of Indigenous Glass Art

A growing number of Indigenous artists are creating artworks in glass, sharing their cultural identities through a medium that was historically associated with European art. These works challenge outdated, narrow perceptions of Indigenous artwork while also adding essential perspectives to the contemporary art world.

Ira Lujan, Quail Grouping, Blown and Sand Carved Glass, Large Quail (Lime/Yellow), 6 x 3 x 4 inches, Large Quail (Lime/Aqua), 5.5 x 3 x 4 inches, Large Quail (Yellow/Purple), 5.75 x 3.5 x 4.25 inches | Image courtesy of Blue Rain Gallery

“Glass has a very unique property, which is that glow — that reflective quality — which allows for shadows and all the varieties of colors which can symbolize different things,” says Tlingit artist Preston Singletary. “It’s a technology that I’m excited to see Native cultures adopting, because it’s an evolution of sorts; it’s not superior to the traditional materials, but it is something that is sort of a counterpoint, and people tend to be pretty excited to see Native designs in glass.”

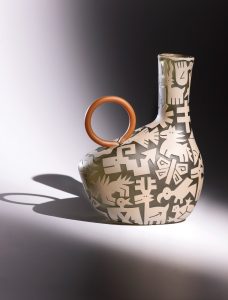

Jody Naranjo and Preston Singletary, Sky Pueblo, Blown and Sand Carved Glass, 15 x 8.25 inches | Image courtesy of Blue Rain Gallery

The groundbreaking exhibition Clearly Indigenous: Native Visions Reimagined in Glass brings national attention to this emerging and evolving movement. Featuring approximately 120 glass works by Native artists across North America and the Pacific Rim, the show reveals how artists have reshaped glass into vessels for Indigenous voices. Co-curated by Dr. Letitia Chambers and Cathy Short (Citizen Potawatomi Nation), the exhibition debuted in 2022 at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The traveling version of Clearly Indigenous was curated by Chambers and is currently on view at the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia, through September 14, before traveling to the National Museum of the American Indian in New York City from October 10 through May 29, 2026, and then on to other venues through 2029.

Dan Friday, Sage Lightning Bear, Furnace Sculpted Glass, 8 x 12.5 x 2.5 inches | Image courtesy of Blue Rain Gallery

“For too long, Native artists’ work was only shown in anthropological museums or museums dedicated to Native art and not in fine art museums,” explains Chambers. “So it’s really important for [their artwork] to be seen in the mainstream.”

Harlan Reano and Preston Singletary, Sun Flower Jar, Blown and Sand Carved Glass, 11.5 x 13 x 8 inches | Image courtesy of Blue Rain Gallery

Clearly Indigenous highlights the glassworks of 29 Native American artists from 26 tribal nations along with four artists from New Zealand and Australia, including Larry “Ulaaq” Ahvakana, Tony Jojola, Preston Singletary, Tammy Garcia, Daniel Joseph Friday, Robert “Spooner” Marcus, Raven Skyriver, Angela Babby, Ira Lujan, Ramson Lomatewama, Susan Point, Lillian Pitt, Virgil Ortiz, Harlan Reano, Jody Naranjo, and many others.

Raven Skyriver and Preston Singletary, Huntress, Blown and Sand Carved Glass, 12.5 x 14 x 31 inches | Image courtesy of Blue Rain Gallery

The exhibition also includes glassworks by non-Native artist Dale Chihuly, who established influential teaching programs that expanded access to the medium for Native American artists in the Southwest and Pacific Northwest.

Chambers traces the origin of the Indigenous glass art movement to the convergence of two significant developments in the 1960s: the contemporary Native American art movement, led by Cherokee fashion designer, artist, and educator Lloyd Kiva New at Santa Fe’s Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA), and the Studio Glass movement, which was pioneered by American artists and brought glassmaking out of industrial settings and into independent studios.

Jody Naranjo and Preston Singletary, Clay Collage, Blown and Sand Carved Glass, 14 x 10 x 5 inches | Image courtesy of Blue Rain Gallery

New [1916–2002] co-founded the IAIA in 1972 and played a pivotal role in shaping 20th-century Indigenous arts education at the school by encouraging self-expression and innovation beyond the confines of market expectations. “For a long time, there was pressure on Native artists basically not to be artists, but for them simply to copy the past [… and] the art that was known at the time of first colonization or of European contact,” says Chambers, who served on the IAIA’s board of directors for a decade in the ’90s and early 2000s. “And it was really Lloyd Kiva New who was the primary mover to break that and to encourage young artists to be artists and certainly to take their art wherever it led them.”

Raven Skyriver, Thresher, Free Hand Sculpted Glass, 17 x 15 x 38 inches | Image courtesy of Blue Rain Gallery

In 1974, New invited Chihuly to IAIA to establish a glass studio. Chihuly installed a hot shop on the school’s original campus at the Santa Fe Indian School and taught there for several years.

The IAIA program, along with others Chihuly co-founded, including the Pilchuck Glass School in Stanwood, Washington (1971), and the Taos Glass Workshop in New Mexico (1999), were instrumental in expanding glass art education to Indigenous youth. Isleta Pueblo artist Tony Jojola [1958–2022] co-founded the Taos Glass Workshop with financial support from Chihuly. The workshop taught glassblowing to Indigenous middle and high school students, with an emphasis on supporting at-risk youth — though over time, it expanded to include all community members. Jojola played a pivotal role in teaching and administering the program for more than a decade, mentoring emerging artists and fostering a new generation of Native glassmakers.

Harlan Reano and Preston Singletary, Spring Flower, Blown and Sand Carved Glass, 10.5 x 12 x 9 inches | Image courtesy of Blue Rain Gallery

“Glass was bound to take off,” Jojola says in a 2021 article in New Mexico Magazine. “Even Lloyd Kiva New knew that. He explained to us that jewelry wasn’t Native, but when silver was presented to us in the way that it was, the Natives took off and ran with it. That’s exactly what happened with glass.”

While Pueblo cultures have a long history in pottery, Jojola is widely recognized as the first Pueblo artist to work in glass using hot-blown techniques. In 1975, he enrolled at IAIA, intending to study ceramics and follow in the footsteps of his grandmother, a skilled ceramicist who specialized in traditional hand-coiled pottery. However, when he discovered glass, he said it was like another form of clay — one he could not touch.

Preston Singletary, Killer Whale Totem | Cast Lead Crystal, 36 x 11 x 8 inches, Image courtesy of Preston Singletary Studio, Seattle, WA

In 1978, Jojola attended the Pilchuck Glass School. He apprenticed under Chihuly and became a member of his team. His works often reimagined Pueblo pottery in glass and can now be found in major museum collections, including the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., and the Denver Art Museum.

At Pilchuck in 1984, Jojola met Tlingit artist Preston Singletary, just two years after he started blowing glass, and this encounter impacted the direction of Singletary’s career. “It just so happened that it was Tony, me, and Larry Ahvakana,” Singletary says in an article for the Pilchuck School. “We were three Native people on the campus learning about working with glass. It was this that planted the seed for me to reflect on my cultural background with my work in glass, the same way that they were.”

Tony Jojola, Blown Glass Vessel and Bears | Blown Glass, Size Unknown, Photo: Additon Doty

Today, Singletary is a leading figure in contemporary glass art, and his work has transformed how people view traditional Tlingit art. His solo exhibition, Preston Singletary: Raven and the Box of Daylight, tells the Tlingit origin story of how Raven brought light to the world. Featuring more than 60 works, the show has been touring nationally since 2018 and is currently on view at the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture in Spokane, Washington, through January 4, 2026.

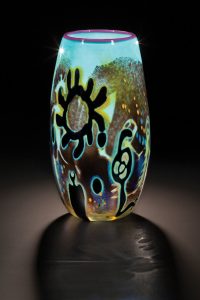

Tammy Garcia, Element 3 | Cast Lead Crystal, 16 x 14.5 x 3 inches, Image courtesy Museum of Indian Arts and Culture

For the last 25 years, Blue Rain Gallery in Santa Fe has represented Singletary’s work. Leroy Garcia, the gallery’s founder, estimates that back in 2000 there were maybe three Native glass artists — Tony Jojola, Marvin Oliver, and Singletary — presenting work at Santa Fe Indian Market, the largest showcase of Indigenous artwork in the U.S. “Now there are probably 50 to 60 Native glass artists that are coming down to the Southwest market or just getting involved in glass,” Garcia says.

Tammy Garcia and Preston Singletary, Untitled | Blown and Sand Carved Glass, 20 x 16 inches, Image courtesy Museum of Indian Arts and Culture

In celebration of this year’s Santa Fe Indian Market, Blue Rain Gallery will host glassblowing demonstrations by Singletary, Dan Friday, Raven Skyriver, Spooner Marcus, and Ira Lujan on August 15 and 16 from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. Additionally, the show Preston Singletary: Banana Republic of Raven opens August 15 with an artist reception and will be on view through August 30; this is a new narrative for Raven, who observes the absurdity and brokenness of the world but believes it’s still worth saving. Singletary explains: “What if Raven was around us today? And where did he go? He’s the central figure in our story, in our mythologies. And at some point, he just stopped doing things, so those stories aren’t coming out any longer. It made me wonder when the next batch of Raven stories — any character, Eagle, Raven, Killer Whale, whatever — are going to be allowed in. So, I’m currently trying to work on new interpretations of mythologies to reflect the current world that we live in. Raven, in my mind, is battling climate change, or he comes back after this long period of time, and he’s sort of looking at the world and wondering what’s going on, and he realizes that there are problems.”

Robert “Spooner” Marcus, Red Gold Seed Jar | Blown Glass, 8.25 x 9 inches, Image courtesy of Blue Rain Gallery

Garcia says that educating collectors about the technical aspects of the glassmaking process was an important part of bringing them into the medium. “We started renting out hot shops so Preston could do public demonstrations at our gallery [and in other cities during art shows, like Chicago and Palm Springs]. We really worked hard at educating people over that 25-year period and invested lots of money into that. And to see it blossom the way it has, it’s so great.”

Another aspect of the contemporary Indigenous glass movement, explains Chambers, is that it includes collaboration between artists of different tribal affiliations. For example, Jojola formed an important artistic relationship with ceramic and public art artist Rosemary “Apple Blossom” Lonewolf (Santa Clara Pueblo), and together, they developed a series of blown glass and clay pieces, which was installed in 2005 at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona. As another example, Singletary has collaborated with Tammy Garcia (Santa Clara), Jody Naranjo (Santa Clara), Harlan Reano (Kewa Pueblo), and others. Additionally, in Clearly Indigenous, artists from the Pacific Rim collaborated with glass artists from the Northwest to make pieces that reflect their culture.

Lillian Pitt and Dan Friday, Spirit Voices – Sally Bag #10 | Blown and Fused Glass, 7.5 x 16.75 x 7.5 inches, Photo: Russell Johnson, image courtesy Lillian Pitt

“When I interviewed the late Tony Jojola,” says Chambers, “he said he felt that Native artists working together is similar to their background communities, where there’s a great deal of collaboration in everyday life.”

The movement, developed by visionaries like Tony Jojola and Preston Singletary, supported by institutions like the IAIA, Pilchuck School, and Blue Rain Gallery, now spans generations and continents. It challenges the idea that Indigenous art must remain tethered to the past. Instead, these glassworks ensure that Indigenous cultures are represented within the contemporary fine art world. Guided by tradition, empowered by innovation, and connected through mentorship, their work is a testament to sovereignty and imagination.

No Comments