19 Jan A Closer Look: Contemporary Still Life Painting

MONKEYS, MATCHES, AND MOCCASINS; books, bowls and bones; spurs, sharks and warriors. Glimmers of bright fall color on glassware, a feather’s delicate texture, the worn glow on a well-ridden saddle or a celebrity’s iconic guitar. These things and more are portrayed in contemporary still life paintings as artists find resonant beauty among limitless choices.

The still life tradition, a realistic painting or drawing of a posed scene of inanimate subject matter, came into being in the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly in the Netherlands. Dutch and Flemish masters often included arranged displays of shells, books, skulls, flowers, insects and at times even dead animals such as game birds. Displays of food were common and richly portrayed by artists such as Pieter Claesz [1596/97–1660], one of the most famous Dutch still life painters of the era. His Still Life with a Fish (1647) reveals his mastery and is at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. So-called “vanitas” still lifes were also popular at the time and contained references to the transience of life and the material world, as in Adriaen van Utrecht’s Vanitas Still-Life with a Bouquet and a Skull (1642), which is rife with symbolism, while other popular interpretations contained didactic, moralistic elements.

Today, still life artists roam far afield from long-ago traditions and bring fresh ideas, humor and creative storytelling to the genre. One thing remains characteristic: Each painting strives for realistic, keenly observed portrayals of its subject matter and each gives the art lover a great deal to think about and discover over time.

Still life paintings invite us to step closer, to see as the artist does — the tiniest reflection, the minute gradations in color as light upon an object changes to shadow or is affected by adjacent hues, the barely visible alterations in the rim of a hand-thrown pot. There is much more to these paintings than one immediate blast of boldness or impression of subject matter. They require quiet contemplation — there’s a story here, a mystery or an insight awaiting discovery, and it reshapes itself according to the viewer.

Five award-winning artists, whose shows often sell out, feel enlivened by the challenges of painting still lifes, with impressive results. William Acheff, Jenness Cortez, Scott Fraser, Kyle Polzin and Daniel Sprick shared recent works and discuss what motivates them.

William Acheff, “Tres Macetas” | Oil on Canvas (Linen) | 26 x 60 inches | 2016

William Acheff, “Tres Macetas” | Oil on Canvas (Linen) | 26 x 60 inches | 2016

William Acheff

For nearly five decades, William Acheff has been honing his ability to produce eloquent still life paintings that articulate Western themes. When asked what continues to draw him to the genre, he says, laughing, “The models don’t have to take a break!” On a more serious note, he explains, “I continue to be fascinated by the challenges still lifes present to achieve balance, perspective and credible themes.”

Acheff enjoys painting older, worn and used objects for their obvious character and unique markings. He feels a special affinity for Native American historical and cultural artifacts and is renowned for his depictions of them: “I sense a common human element,” he says, “that most people can relate to from their own personal experiences. I paint from life so there is much more information available in seeing and perceiving not only the objects but the space around them.”

While he doesn’t create preliminary sketches of an entire composition, if there is a specific, unique artifact in it — such as a revolver — he works up a meticulous drawing according to the scale of the other objects before incorporating it on the canvas. He invariably sits 6 to 7 feet away from the setup in the early stages, but, as the painting progresses, moves continually closer to absorb every minute detail.

We’ve all had the experience of taking for granted objects that surround us routinely — then one day we see them as though for the first time. Recently, Acheff had been considering selling his extensive pot collection and photographed them with descriptions and values. Then, at the last minute, he decided not to sell. But re-examining them sparked an idea and weeks later he painted three of the bigger pots on a large canvas. Tres Macetas is the distinctive result. “The simplicity of three large, plain pots with a red blanket was, for me, stunning. If I had sold the collection, I would never have created that painting!”

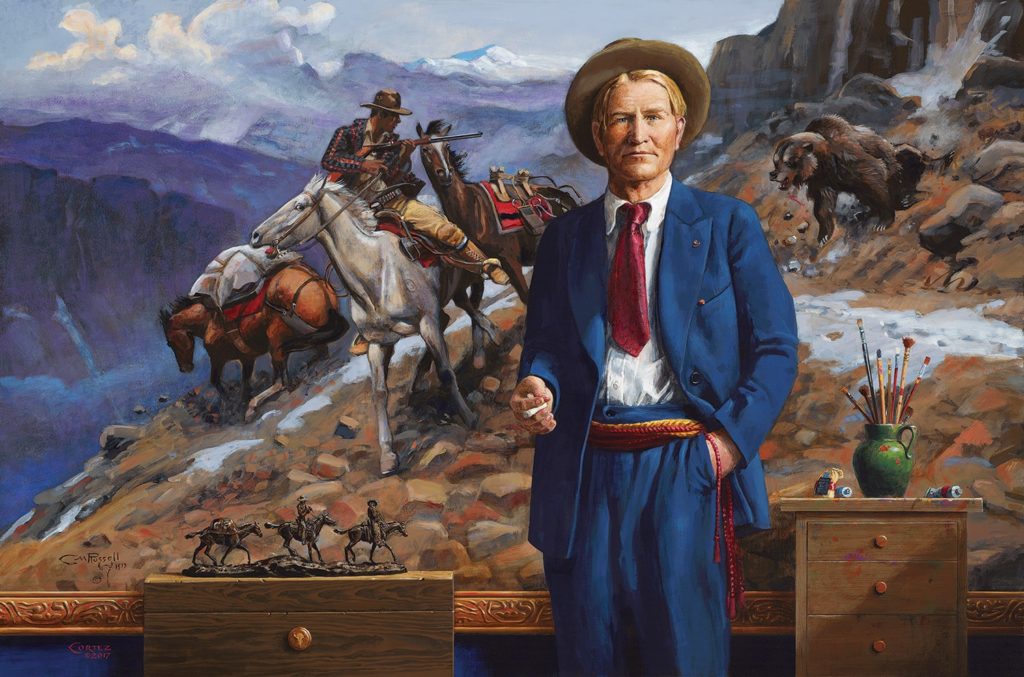

Jenness Cortez, “The Storyteller” | Acrylic on Mahogany Panel | 24 x 36 inches | 2017

Jenness Cortez, “The Storyteller” | Acrylic on Mahogany Panel | 24 x 36 inches | 2017

Jenness Cortez

Growing up in Southern Indiana, Jenness Cortez loved the paintings of C.M. Russell. In her recent painting, The Storyteller, she pays homage to the famous Western master — an approach she often takes. Portraits tend to focus solely on a central figure’s physicality, but Cortez includes still life elements here that reveal far more about Russell. It’s a fine example of “showing” rather than “telling.” Posed in front of one of his well-known paintings — Crippled but Still Coming — Russell is dressed in his own unique style, with brushes, paint tubes, a bronze sculpture and the Bull Durham tobacco pouch that was always within arm’s reach; each element is emblematic of the whole person, the story behind the man.

Although still lifes are not Cortez’s exclusive focus, they are an important part of what she is known for. She believes they must incorporate two essential components: they must attract, hold and please the eye, and they must tell a story or deliver a meaningful idea or surprise. Achieving these goals is not always easy.

“The ability to really see is a hard-won skill,” she states, “just as important as the skill of the hand. For most of us, it’s the product of long practice, will and patience. In my case, I also credit the power of daily meditation. … When I made a serious commitment to it years ago, the immediate effects were improved focus, precision and stamina — benefits that have continued to grow.”

When a story concept strikes, Cortez searches for the perfect group of elements to illuminate it and lend strength to the final composition. A favorite object is the clock. “Clocks arrest the eye and mind because time is such an important filter in our lives,” Cortez says. “Our thoughts tend to dwell in the past or future, but ‘stopping the clock’ is central to the task of every visual artist, and I like to enlist its literal inclusion to help me accomplish that.”

Scott Fraser

Thirty years ago, a young Scott Fraser returned from a year in Europe with his mind filled with work by Old Masters and contemporary artists he’d viewed while there. He set his sights on becoming equally skilled. Today he is highly regarded across the nation for his intensely realistic and imaginative still life paintings.

Scott Fraser, “Monkey Inferno IV” | Oil on Board | 43 x 24.75 inches | 2017

Scott Fraser, “Monkey Inferno IV” | Oil on Board | 43 x 24.75 inches | 2017

“For me,” says Fraser, when asked what comprises a successful still life, “it could be its narrative quality, the handling of the paint or use of color, or the artist’s powerful composition.” In his own work, he strives for strong relationships between objects and theme, drawing on humor, color, nuance, art history and family references.

Monkey Inferno IV exemplifies how Fraser combines personal and intellectual processes in the development of a painting. When his children were young, he built a tramway out of clotheslines and pulleys and made a little gondola out of string and a sardine can for them to transport small toys (and sometimes the pet mouse) back and forth. A little raft from those times, like the one depicted in this painting, still hangs from a plant in his studio. Fraser decided to incorporate them into his Monkey Inferno series.

The artist explains: “It’s true I am channeling some old Warner Brothers cartoons, but there is also a historic reference. Seventeenth-century Spanish realist Juan Sánchez Cotán created still lifes in framed dark niches, which were my inspiration for the shadow box here. The curve achieved by the piled up matches is reminiscent of a catenary arch such as Cotán might have painted. There is a strong visual tension between the jumble of match sticks, the surprised duck and the wayward monkeys with their elaborate rigging — the lit match is crucial both to the narrative and the composition.”

This piece contains more than 1,000 individually painted matches — no small challenge for Fraser, who works always from life. For extremely detailed passages, he uses a magnifying glass on both the object and his painting. As he tells it, “Things like bugs on crackers are a killer!”

Kyle Polzin

Growing up in South Texas helped shape the man and the artist Kyle Polzin would become. His appreciation of the beauty and heritage of his part of the West deepened, and for the last 10 years the majority of his paintings have been still life scenes richly rendered with classic grace.

Kyle Polzin, “Trigger” | Oil on Canvas | 24 x 45 inches | 2013

Kyle Polzin, “Trigger” | Oil on Canvas | 24 x 45 inches | 2013

“I love vintage objects with lots of wear and tear and the patina of time on them. I’m also curious about their histories or about the people who once owned them. In my paintings I try to bring out these characteristics and through my composition let them tell their story. I think composition is the most essential element of a good still life; lighting is a close second.”

In each painting, Polzin zeroes in on a few key elements that tell an interesting story. History is always an important influence and he enjoys learning about each of his subjects to make them as accurate as possible. “Finding new compositions is always challenging,” he says. “Especially when painting saddles!”

Trigger was a special pleasure to create. Always a Willie Nelson fan, Polzin wanted to paint Nelson’s Martin N-20 nylon-string classical acoustic guitar, which the star had dubbed “Trigger.” Back in the day, when asked why he’d named his guitar that, Nelson is said to have quipped, “Roy Rogers had a horse named Trigger. I figured this is my horse!” With Nelson’s consent, Polzin applied his considerable talent to reproducing the legendary instrument in all its historic perfection. It has all the qualities Polzin looks for in an ideal subject — worn to a glow after four decades and more than 10,000 shows, covered with dozens of autographs from such greats as Leon Russell, Gene Autry, Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings and others. As a finished painting, it symbolizes a segment of Western culture that is as American as horses, cattle and ranch life.

Daniel Sprick, “Still Life with Chocolates & Orange” | Oil on Board | 24 x 30 inches | 2017

Daniel Sprick, “Still Life with Chocolates & Orange” | Oil on Board | 24 x 30 inches | 2017

Daniel Sprick

For more than 40 years, still life paintings have been a significant component of Daniel Sprick’s subject matter, although he is equally well known for his evocative figurative works. An admirer of such masters as 17th-century Dutch Baroque painter Johannes Vermeer, whose treatment and use of light in his domestic interior scenes of ordinary life have influenced many, Sprick believes in the pursuit of genuine often-understated beauty. With each painting, he investigates the form, light and shadow of his posed objects and strives to reveal — through color, harmony, values and placement — their indescribable emotional qualities.

The compulsion to paint a specific scene can come at any time. Whatever its source, it is what the artist makes of it with his personal skill and intuition that shapes the result. “I work from direct observation of a setup I’ve carefully considered,” says Sprick, “or I may walk into my kitchen and see a perfect mess I’d like to paint.”

As the artwork progresses, Sprick makes thousands of decisions, often unconsciously. The result is a unique signature style. Sprick prefers to choose fewer objects rather than more, moving them around physically to discover when their visual properties click into alliance with each other. How this happens can be seemingly random, but the results are anything but chaotic.

For Still Life with Chocolates & Orange, it all began because the artist had some squares of chocolate lying around and began experimenting with groupings of ceramic, glass and pewter serving pieces to see what developed. He sought ways to add variety with color and texture, harmony through vertical and horizontal variations and a sense of gestural space, and he chose a cool north light from a nearby window. The emotional tone of this painting is sublime — a subtle, quiet meditation on ordinary objects. In a remarkable way, although the objects are still, they seem posed on the verge of action.

No Comments