09 May No Doors, Jivan Lee

ONE EVENING LAST WINTER, Jivan Lee set up his easel outside his house near Taos, New Mexico, intending to paint the long field in front of him, patches of winter trees and layers of mountains beyond. As he stood there taking in the sunset glow, he happened to look to his right. There was an old fence, tall dry grasses and another fence a little farther away. It wasn’t a conventional, eye-catching scene like the one straight ahead. Still, on impulse he gave his easel a quarter-turn, pointing it toward the fence.

“Fences #2 – Glowing Light” | Oil on Canvas | 48 x 30 inches | 2018

“I thought, ‘Oh man, that’s an uncomfortable subject, but I really like it,’” he remembers. Uncomfortable because it wasn’t the traditionally beautiful scene he expected to paint. Yet in that moment, the view that became Fences #2 – Glowing Light was completely compelling. “What got me was the explosion of luminosity in the grasses in the foreground and the fences and rhythms and horizontal lines,” he says. “It’s not a gentle painting, which was unexpected because I was actually feeling gentle that day. But you need to be willing to turn 180 degrees, literally and otherwise. You need to do your best to not have a preconceived notion, or at least if you do, to hold it loosely.”

That’s how the 33-year-old painter approaches artistic decisions, but it’s also how he relates to life. He’ll steer his paint-and-canvas-loaded Toyota truck in a chosen direction but keep his peripheral vision wide, ready to turn the wheel if an inner prompting gives him the nudge. In life, he goes straight for a goal when he knows what he wants. But he’s also willing to listen to intuition’s quiet voice and take what others might consider a risky leap.

Denver-based art historian Stephanie Grilli, who got to know Lee a few years ago while co-curating a show he was in at the Metropolitan State University of Denver’s Center for Visual Art, perceives not only Lee’s environmental passion but also a subtle sense of spirituality in his work. “You can clearly see in his paintings that the visual is a pathway to something else,” she says. “That intensely physical aspect of his work is taking you into that which is ineffable and cannot be explained.”

It seems appropriate, then, that Lee’s father, a contracting company owner and “Renaissance man on the side,” as Lee puts it, gave his son a first name that in Sanskrit means life, or breath. With fine red hair tied back when he works, the artist moves quickly, focuses intensely and engages people easily with his warmth and thoughtfulness. But also, like breathing, he’s aware of the need for coming in and going out, balancing family — his wife, Clara, and their one-year-old daughter — and his art.

“The View from Blueberry Hill” | Diptych, Oil on Panel | 36 x 78 inches | 2017

“The View from Blueberry Hill” | Diptych, Oil on Panel | 36 x 78 inches | 2017

Fatherhood has kept the circumference of Lee’s painting excursions to within a half-hour of Taos since his daughter’s birth. As a result, the solo show that opens June 29 at LewAllen Galleries in Santa Fe reflects his explorations on other levels. Among these are multiple-panel pieces that for Lee suggest distinct moments of attention, like stills from a film, the eye drawn to sections of a landscape rather than taking it all in at once.

Featuring more than 25 new works, Leave it at the Door runs through July 29, with an artist’s reception on opening night, June 29. Lee sees the show’s title as an invitation for viewers to shed preconceptions and distractions when they enter the gallery doors. Just as importantly, he believes, painting on location means leaving everything else inside when he steps out the door. “This is about the outdoors,” he says. “It’s about leaving all doors behind and just being present with a tactile, visual experience.”

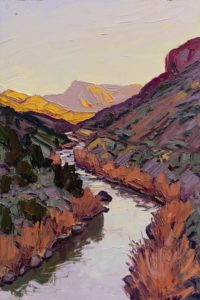

“River Bends – Early Light” | Oil on Panel | 36 x 24 inches | 2018

Growing up in the Catskill Mountains near Woodstock, New York, Lee was a big fan of leaving doors behind, spending as much time as possible outside. Drawing wasn’t an obvious passion at the time, although he enjoyed it. More importantly, his mother, a talented realist painter, created “a spirit and atmosphere in the house that was very open to artistic expression,” he says. Still, he found himself leaning toward science, called to learn about the earth and its care. At 17, he received a full-tuition science scholarship to Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.

Skipping his high school senior year, in 2007 Lee earned both a general bachelor’s of arts degree (with a focus on biology) and a master’s of science degree in environmental policy from Bard. He also studied drawing and painting, just for himself. Following graduation, he painted in New York for a few months — at the time his work was primarily figurative — and then headed west to visit a friend in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Waylaid for a year in Albuquerque with the debilitating effects of Lyme disease, he eventually began working as a consultant with non-profits in the environmental field.

At one point a suggestion came to Lee, as many of his life and career-shifting ideas have, in a dream. The dream recommended he check out University of New Mexico at Taos for a possible job. In the serendipitous manner in which much of his life seems to unfold, he drove into Taos for the first time and decided to pull off in a parking lot to get his bearings. He looked up and saw he was parked directly in front of the dean of instructions’ office. The dean pointed him to Taos Pueblo’s Red Willow Center. There, among other initiatives, Lee taught courses and founded the Project for Art and the Environment, using the creative process to help students deepen their ability to understand and work with complexity in environmental issues.

In 2010, a series of dreams suggested that Lee could make a living with art, and he followed their advice. As his paintings found their way to viewers and collectors, gradually at first and then more broadly, he experienced an important insight about how humans alter their perspectives and actions. He saw first-hand how his expression of the landscape moved people, sometimes to tears, and allowed them to see the land in a new way. “When I was doing environmental work it wasn’t landing as deeply as necessary to see change happen, and I realized people need to care enough to make choices,” he reflects. “We’re not logical choice makers, we’re emotional choice makers.”

“Taos #4 – Towards Sunset” | Oil on Linen | 40 x 60 inches | 2018

“Taos #4 – Towards Sunset” | Oil on Linen | 40 x 60 inches | 2018

In another significant dream, after he’d begun painting on location, Lee was instructed to check out the art of New Mexico painter Louisa McElwain. He’d met McElwain some months earlier when she was selling farm implements at her house, but he’d almost forgotten her name and was only vaguely aware that she was a painter. When he saw her work he saw his own artistic possibilities blown wide open. “I thought, ‘You’re kidding me! I can paint that big on location?’” Known for completing enormous paintings on location, McElwain expressed excitement about the younger artist’s direction and generously offered him practical tips, including the use of flat-edged painting implements. She favored palette knives and trowels, while Lee employs long-handled silicone spatulas to quickly apply luxuriously thick, almost sculptural amounts of paint, producing rhythm and pattern through the strokes themselves and adding another dimension to an image. Conversations with acclaimed Taos painter Walt Gonske also revved up Lee’s energy and commitment to observing and painting from life.

At an overlook above Taos Gorge, Lee turns off his truck as the sun is dipping down. He pulls on layers of warm clothes against the sharp wind and secures a large aluminum easel to the back of the truck, weighing it down with a sack of rocks. He picks out a 40-by-60-inch canvas, squirts prodigious amounts of non-toxic, walnut-oil-based paint into the Tupperware tub that serves as his (resealable) palette, and rapidly sketches a few loose forms, just enough to indicate a basic composition.

“Taos #3 – Settling into Night” | Oil on Panel | 36 x 30 inches | 2018

“Taos #3 – Settling into Night” | Oil on Panel | 36 x 30 inches | 2018

As shadows lengthen, Lee paints energetically with various-sized spatulas, regularly sprinting away to observe his work from a distance and running back to add more paint. He grins and bounces with excitement and nervousness as the sun sinks lower. “I hope this is my standard freak-out during a perfectly fine painting, but I don’t know,” he says. And later: “The middle note in the harmony of the shadows was missing — I just got it!” And then, noticing roughly cloud-shaped areas of bare canvas: “Oh no, the clouds! I totally forgot!” By the time the truck is almost in darkness, Lee has added clouds and other touches and packed it all up, including the spectacular Taos #4 – Towards Sunset, the fruit of a chilly but gloriously exhilarating two hours on site. It will receive a couple of hours of finishing touches in the studio.

Ken Marvel, co-owner of LewAllen Galleries, believes Lee’s visceral connection with the land is a large part of the artist’s appeal. “His work resonates the deep feeling he has for the earth, the water, the sky. People really appreciate the fact that he puts so much into his paintings. They’re accessible but sophisticated,” Marvel says.

For Lee, the power of art is still something of a delightful mystery. “It’s color on a surface, and yet it does something,” he muses, referring to his own experience as well as that of the viewer. “Honestly, for me, there’s something here that’s alive, that has a reality I didn’t know was possible, and I’m going to see where it goes.”

No Comments