08 Nov A Sense of Scale: Kate Starling

THERE’S THE POSTCARD VERSION of spectacular Western American landscapes, places such as national parks, for example, that shout out, “This is beauty!” And then there’s the more common and intimate magnificence that most people drive on past. This second kind of beauty is what artist Kate Starling is most often drawn to. It’s the landscape’s less public face that over the decades — as a teenage outdoor adventurer, geologist, National Park Service summer employee, and then painter — she has absorbed and come to know on familiar terms.

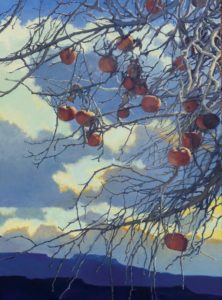

“Apple Tree” | Oil | 60 x 40 inches

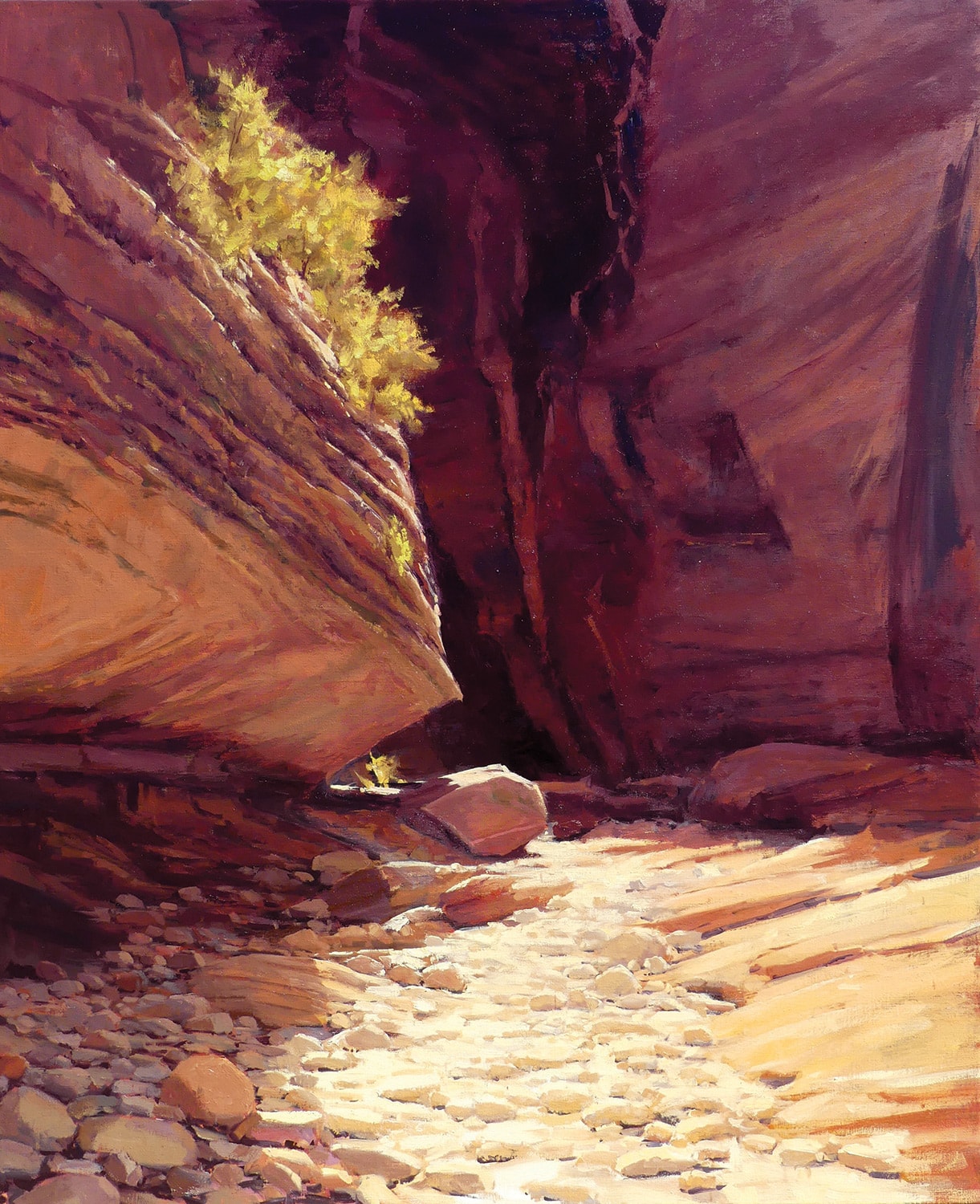

In her most recent works, which include large, closely cropped images of Southern Utah landforms, Starling invites viewers to step into the cool shadows of a slot canyon or to reach out and feel the hot, smooth surface of a red rock wall. In this way, the 62-year-old artist’s sensory experiences are almost a visceral element in what she paints: the scents of desert vegetation and earth, the constantly changing temperature in sun and shade, the sounds of birdsong and wind. Her largest paintings — up to 7 by 6 feet — are created in the studio at her Rockville, Utah, home. But what she expresses always starts with being on the land.

This January 12 through 27, Starling’s landscapes will be exhibited at the 2019 Coors Western Art Exhibit & Sale in Denver, Colorado. And her large-scale paintings are also among the works she’s producing for a summer show, May 11 to July 27, 2019, at the Southern Utah Museum of Art in Cedar City. “Kate is re-examining the landscape in a new way, taking the freedom to manipulate and experiment with the scale,” says Jessica Farling, the museum’s director and curator. “I’m thrilled to have the opportunity to showcase her work.”

Starling’s relationship with the Western landscape began on relatively mild terms, although the outdoors were always part of her world. She grew up in Phoenix, Arizona, at a time when the city was smaller and the surrounding desert was within easy reach. Her father worked in circulation for Arizona Highways magazine, so the visual beauty of her home state was always on the table, literally, and in her mind. As a child, Starling, her two siblings, and their parents enjoyed camping and fishing trips. “It was not super-adventurous, but it left an impression,” she says. Then, in her high-school junior year, her experience of the outdoors underwent a radical change — and so did she.

“Lee Valley” | Oil | 72 x 48 inches

“Lee Valley” | Oil | 72 x 48 inches

That year, two Eagle Scouts who’d experienced hard-core adventuring as teens, and continued into their 40s, were leading first ascents of mountain summits in Arizona and Mexico, among other extreme sports. The pair started a Challenge Club at Starling’s high school, taking kids on rock climbing, kayaking, and backpacking trips. For Starling, it was a new way of connecting with the land, one that became a way of life.

Art was always there as well, although a focus on oil painting, and landscape in particular, took longer to come to the fore. From a young age, Starling had a non-stop impulse to create, making things from whatever was on hand. She took art classes periodically, while earning a geology degree from Northern Arizona University and while working as a geotech for several years in California and Texas. In Utah, she finally connected with the artist who set her on her current path.

It was the mid-1980s, and Starling and her husband, Jim, who worked at Zion National Park, were living near the park’s entrance in the small town of Rockville. Starling decided to return to school to become certified as an earth sciences teacher. At Southern Utah University in nearby Cedar City, she was about to begin student teaching when she took a painting class from a young, Chinese-born painter named Yu Ji. At the time, much of college-level studio art was influenced by Abstract Expressionism. Many art professors eschewed formal instruction and encouraged students to “Just do your thing!”

“Gooseberry Cloud” | Oil | 50 x 60 inches

“Gooseberry Cloud” | Oil | 50 x 60 inches

Ji was an academically trained artist who “didn’t know he wasn’t supposed to teach realistic drawing and painting,” Starling says, smiling. As a student in her 30s, she was ready and open to learning as much as she could. A few years later, she took graduate courses in painting at the University of Oregon, but it was those two years under the mentorship of Ji that established her foundation for painting. While her instructor’s focus was on portraiture and the figure, Starling gradually worked out how to transfer the elements of composition, value, and application of paint to depictions of the natural world.

In the rural community of Rockville, where she and Jim have lived ever since, the artist’s garden produces much of what her family eats, and a newly planted vineyard promises future homemade wine. “It feels really good to stay connected with the earth, not just looking at the landscape,” she says. But of course looking at the landscape is also an essential part of what she does. And it was this Southern Utah terrain that first turned her artistic attention toward the land.

“Abandoned Highway” | Oil | 24 x 30 inches

Now as Starling drives or hikes not far from her home, the stark desert light and strong shadows on familiar landforms call her to stop, take photos, paint oil sketches, or make a note to return. “Being here becomes part of the process,” she says. She recalls her early years of adventuring, when she and her friends were impatient to keep moving. They would scurry to a summit, stay five minutes, have a snack, and descend. In those days, as well, she was often frustrated by the inadequacy of words to express the landscape’s power to move her. Becoming a painter not only forced her to slow down, stay in one place, and closely observe, but it also provided a visual vocabulary to share the pleasure and wonder she feels when she does.

“Moenkopi Frieze” | Oil | 50 x 48 inches

Sharing Ji’s belief in the value of working from life, Starling painted on location for many years. For reference and smaller paintings, she still does. A few years ago, however, an invitation to show in a spacious venue sparked a shift to work in a larger scale. After her first 6-by-6-foot painting, she was hooked. “It was so much fun, it made me realize how scale can really change perception. Not like trompe l’oeil, but it lets the viewer feel like you can walk right into it,” she says. Clear Creek, for example, is a 4-by-3.3-foot canvas in which the eye follows a sun-warmed creekbed past angled sandstone and backlit shrubs and into the shadowed depths of a narrow slit between rock walls. Likewise, with Moenkopi Frieze, Starling decided the image was worth producing big. She likes the idea that while viewing the painting, one feels like they’re actually standing in front of a smooth but creviced rock wall, sandwiched between layers of looser stone.

Whatever the scale, Starling likes to imagine her paintings having an impact on viewers, nudging some, perhaps, to a greater gratitude for the beauty and value of the land that Westerners call home. “As Americans, we’re proud of the landscape. We designate parks. But I want people to feel appreciation for places that are more mundane, not as spectacular — to feel a sense of seeing it more intimately and close up,” she says. “I would like people to take more care.”

Regardless of the viewer’s response, Starling finds herself continuously enriched simply through the process of painting. She remembers Ji asking his students as they stood at their easels, “What are you trying to say?” Her response, perhaps to herself at that time, was: “I’m just trying to paint this thing!” Decades later, while she is infinitely more skilled than she was starting out, the challenge of conveying the landscape’s immersive, multisensory presence through paint still keeps her inspired. “It’s all integrated,” she says of the experience. “There’s still just the joy of seeing what I can do.”

No Comments