14 Jan Backstage with Aaron Morgan Brown

TO UNDERSTAND AARON MORGAN BROWN’S PAINTINGS, it helps to know that he spent many summers hanging out in the Creede Repertory Theatre, located in a tiny mountain town in Colorado, where his father worked in the late 1970s. In those days, the company staged plays out of the old movie house, where the actors also made costumes, designed sets, and built props. And though the performances exposed Brown to a comprehensive list of plays and productions, it was life behind the scenes that truly captured his imagination.

“My dad was the company’s photographer but also an abstract landscape painter. Both of those things found their way into my work — the idea of documentation and seeing the world through photographic imagery,” he says, adding that even more specifically, it was being backstage, watching the actors come and go and the nuts-and-bolts of a production that inspired him. “You know those old depictions of the moon hanging in the sky, and the moon is made out of wood — that weird surreal illusion? I found that to be the most interesting part of the theatrical experience.”

Annunciation | Oil on Panel | 30 x 60 inches | 2015

Reminiscent of post-Renaissance painter Caravaggio, often considered the art world’s first “film maker” for the theatrical quality of his art, Brown, too, prefers to create artworks with multiple layers of drama and meaning, works that contain entire scenes and stories. He calls his work “pictorial orchestrations,” a style he developed over time by honing his personal visual philosophy. Not only linked to the external, his work is very much tied to his inner self. “I’ve always seen the external world as this place that’s rational and chaotic, fraught with duality. For me, painting is a philosophical search but also a technical one where I’m searching for meaning on a 2D surface.”

Like Minds | Oil on Canvas | 60 x 44 inches | 2018

Growing up in the theater, Brown was always drawing and has come to believe that he intrinsically expresses himself through art. “The lack of [language] is important,” he says. “It’s about how much can I express in purely visual terms by the way I arrange things. It’s how I see painting: silent theater.”

Incorporating text in his paintings would certainly make the job easier, however, Brown avoids it in favor of letting the scene carry the story. Take the painting Embargo for example, an oil on panel that — like much of his art — works as an allegory; in this case, for the twilight of the Industrial Age. The painting, rife with dilapidated objects in a state of atrophy, projects a sense of history and nostalgia, but — in the midst of it all — is a small child on a playground seahorse spring-rider. “That’s the thing about my work,” says Brown, “there’s this tension that things might actually be happening.”

In his latest series, Spirit of the West, there is a mythological dimension as well. “The iconic cowboy,” he says, “could be seen as a spiritual seeker, and the horse could be the spirit of the land itself. It is an elemental force, rolling like a wave over the Western topography and up into the heavens above, charging everything with a dynamic-creative force.” But he warns that the semi-transparency of the composition is a sign that the imagery is not meant to be taken literally: It’s symbolic, operatic, a metaphysical Western. “In my view, the horse-spirit is not vanishing; it is becoming part of the earth and sky, and our collective memory, and thus, it will live always.”

Absolution Du Jour | Oil on Canvas | 45 x 54 inches | 2016

While much of his work veers into the realm of magical realism, the objects come from everyday things he’s encountered. He also often includes children as subjects. Brown explains: “In terms of art, I see children as earthly avatars, these little, vibrant beings who are in a state of becoming. They represent aspects of the human spirit that we hope never to lose. They make good protagonists, because they carry whatever we might want to project onto them. With a kid, there’s a sense of helplessness but also the potential to grow and make sense of the world.”

For the most part, Brown doesn’t start with a concept, but instead plays with images, like painting with a tinker toy set. Generally, he imagines an environment — the gas station in the case of Embargo — then introduces objects to the scene to see how they play off each other. Eventually, a theme presents itself. “Usually, painting is a form of improvisation — it’s intuitive,” he says. “When something starts to form, I’ll throw in other objects that support the theme.”

Borderland Revisited 2 | Oil on Panel | 50 x 30 inches | 2016

As for the objects that make their way into his paintings, he says they carry associative luggage. “Images have a certain cultural cache that comes from their use and abuse. It gives them power but also weighs them down, like luggage,” he says. And so, the images he uses almost always have layered meanings and can evoke memories for viewers that alter perceptions.

These days, Brown is living a bit of a nomadic life, accepting artist residencies and trying out different places to live. The painting, Borderland Revisited 2, delves into his feelings of being uprooted. “The experience of being an outsider is something that resonates with me internally,” he says. “It’s probably a common experience with people who have been chased out of their own country, or have lost their job, or marriage, or their house to a natural disaster.”

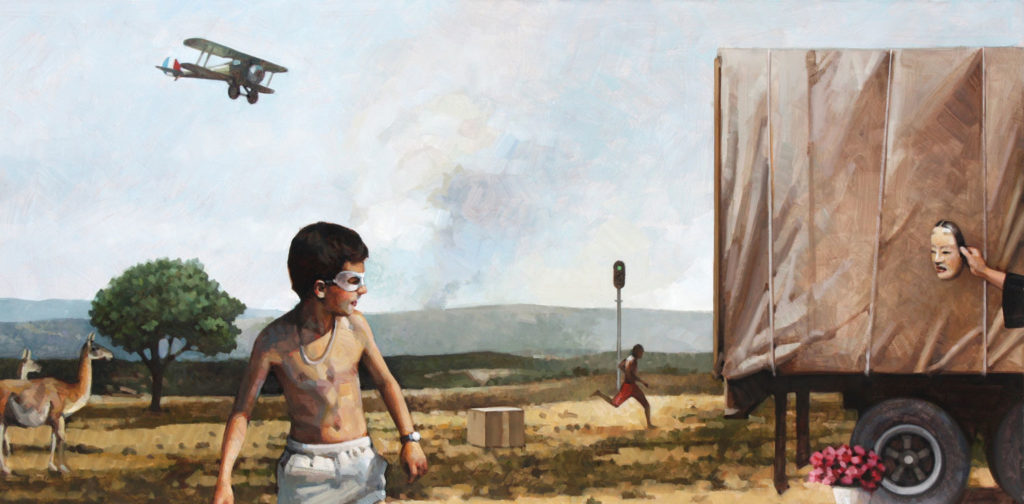

“Free Range” | Oil on Panel | 23 x 40 inches | 2017

Unlike the innocent child in Embargo, this child shows up wearing a mask, hiding his features, trying to blend in. The boy directly reflects Brown’s sense of finding a place where he belongs, a theme that works as both a personal and political allegory.

“You have to look at all my work as if in a dream,” he says. “It has this ‘unreality’ quality. Memories intrude when just walking down the street — something may appear, but it comes out of yourself. It may take the form of an animal or object, but it’s all related to memories and experiences. The way it’s expressed is in terms of dream language.”

Spirit of the West 1 | Oil on Canvas | 72 x 48 inches | 2017

Beyond narrative, there’s also a sense of blurred lines and time moving at uneven pacing through his paintings. In Like Minds, buffalo roam urban streets as if the sidewalks are the truly odd thing here. “It’s about boundaries,” he says, “boundaries of the West itself. Where does one stop and the other begin? I think there is something wild in all of us, which is why we cling to the romance of the West, even though we are compelled to tame it.”

Upon first glance, The Battle of New Lexington, (Prelude) appears to be a historic work, but then the scene shifts from the past into the present in a manner that makes one believe that time travel was possible. “I’m interested in the passage of time as an idea, a phenomenon, and as a perception of reality,” Brown says. “That painting came out of going to Civil War reenactments. It struck me as fascinating, kind of like being backstage at the theater. But something was also relieved in the artificiality of it, about the passage of time and our perception of the past. It’s a strange juxtaposition to see both those things happening at once, so I tied a balloon to the shovel in the center to join the past and the present. Our current culture seems superficial compared to what was such a bitter struggle; the stakes were so high; the sense of importance was so great compared to today’s pop culture,” he says, adding, “There’s irony attached to that shovel.”

Brown’s work will be featured at the Birger Sandzén Memorial Gallery in Lindsborg, Kansas, in June 2019. He is represented by the Gerald Peters Gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico; Walker Fine Art in Denver, Colorado; and Weinberger Fine Art in Kansas City, Missouri.

No Comments