13 Mar The Eames Legacy

IF YOU’VE EVER SAT IN A CLASSROOM, waited in an airline terminal, or worked in a cubicle, chances are the chairs and tables were designed by Charles and Ray Eames, regarded as one of the most influential design teams of the 20th century. Starting in the 1940s and operating for 45 years, their brick-and-mortar firm, Eames Office, in Venice, California, wowed America with a simple, yet elegant midcentury modern aesthetic. Enter mesh wire chairs; a fiberglass chair resembling a Pringles potato chip; the iconic molded plywood chair, bent and shaped for comfort — yep, that was them.

One of the many games designed by the Eames, House of Cards, 1952, ©2019 Eames Office, LLC (eamesoffice.com)

Visitors to the Denver Art Museum (DAM) will see many iconic Eames products (furniture, movies, textiles, toys, ceramics, photography, and more) during the May 5 through August 25, 2019, exhibit Serious Play: Design in Midcentury America. The theme emphasizes playfulness and its influence on postwar America, when the country suddenly became more affluent and open to new ideas. Jointly produced by the Milwaukee Art Museum and DAM, the exhibition features more than 200 works by renowned and lesser-known designers.

Eames molded ply- wood chair, DCM, 1946

Serious Play encourages museum-goers to experience how design impacts and connects to daily life. “We hope the public comes away with the larger idea about how America embraces playfulness and whimsy after the trauma of World War II,” says DAM Curator Darrin Alfred.

Among the many quips for which Charles Eames was known, one of his most popular taglines was: “Take your pleasure seriously.” For the Southern California couple, work was fun; and that revelry resulted in a plethora of diverse projects. They filmed clowns for the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, and developed blueprints for a national aquarium for the U.S. Department of the Interior. In 1956, on the NBC show “Home,” an Eames chair and ottoman debuted. It had — as the charismatic Charles described — the look of a “well-used, first-baseman’s mitt.” The lounge chair of leather and rosewood became an overnight status symbol, and remains one of the most popular high-end chairs today.

Charles and Ray Eames photograph an early model of the exhibition Mathematica: A World of Numbers …And Beyond, 1960.

The Renaissance couple shared complementary skill sets. He was an architect. She was a schooled painter with an exceptional eye for placement and color. They met at Michigan’s Cranbrook Academy of Art, and, as the story goes, instantly fell in love. They married in 1941 and moved to Los Angeles, California.

Eames plastic armchairs on various bases, 1950

Outgoing and engaging, Charles considered Ray his equal, often saying, “Anything I can do, she can do better.” Both possessed a zeal for life and an insatiable curiosity to learn about everything around them.

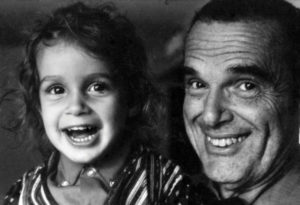

Eames Demetrios, their grandson and the director of Eames Office, recalls that during visits to his grandparents’ home as a child, they were eager to hear about his world, rather than talk about their own. “They were very present with us,” he says. “They would ask what movies and plays we had seen. They wanted to know about us. They played with us, but also played with us intellectually.”

Eames multi-screen projection “Think” at the IBM Pavilion, New York World’s Fair, 1964

Charles and Ray would prepare the house for their grandchildren in a way that would maximize joy and creativity. “They cleared out their studio and made it a mecca for us kids,” says the eldest granddaughter, Carla Atwood. “There were bunk beds, long tables for us to draw [on], and Tinker Toys to play with.” They even hung a long rope inside the house so that the children could swing on it and topple stacks of little paper boxes, she recalls. “They would think about what we would need as children and how to make it a special time for us.”

Ray Eames with Polaroid SX-70, in Charles’ office, 1973

Few American designers possess such staying power and fame. A litany of books have been written about the power couple and TV shows, such as “Frasier” and “Gossip Girl,” have featured Eames furnishings in the sets. There’s a typeface font named after them, by House Industries, called the Eames Century Modern typeface. And in recognition of their vast contribution to American culture, the U.S. Post Office issued a set of 16 stamps in 2008, each one representing a medium in their portfolio.

Today, Eames furniture and home accessories are ubiquitous, appearing in travelling exhibitions, more than 40 museums worldwide, private homes, corporate offices, universities, and elsewhere. Fans can purchase Eames goods from retail stores, such as Design Within Reach, and online hubs, namely eBay and Amazon.

Curator for the Oakland Museum of California, Carin Adams presented an exhibition of nearly 400 Eames artifacts in October 2018. Her assessment of their oeuvre? “The work of the Eames was not just about products. It was the ideals and methodology; and the way they collaborated and iterated, and continued to think about design as problem solving.”

Eames Lounge Chair and Ottoman, 1956

Unlike their peers who primarily sketched ideas, they always sketched and built their own prototypes to understand how a manufacturer could make their toys or furnishings en masse. When something did not work, they remained undaunted. Each mistake was an opportunity to experiment with another method or material. The principle of “learn by doing” led them like a guiding light throughout their career.

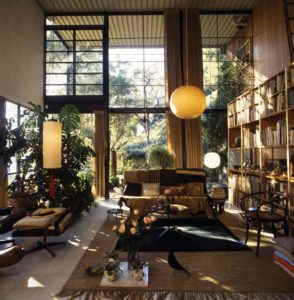

The Eames House living room, photographed by Antonia Mulas

For example, it took several years before they were satisfied with their first molded plywood chair. They had assembled a machine they called the Kazam!, an apparatus made of scrap wood and a bicycle pump to mold plywood into chairs. Invented in their apartment in Los Angeles in the early 1940s, the Kazam! was instead used to make a prototype leg splint to show to the U.S. Navy, according to Demetrios. It all started when a friend, who was also a doctor, mentioned that the stiff, metal splints were causing further harm to injured servicemen. Once the Navy saw the Eames’ lightweight plywood design, they asked for some modifications in the prototype and requested 5,000 splints. After that, the Navy placed an order for 150,000 more.

“There is also a document where Charles makes a list of items for the mass production of splints where he indicates the need for ‘6 Kazam!s,’” says Demetrios. “This indicates that in 1943, Kazam! was still the favored term for the improvements they made.”

It was also through the Kazam! that the couple made the first successful molding of plywood into compound curves. Their technology was later applied toward everyday furniture.

Charles and Ray Eames outside their home in the Pacific Palisades neighbor- hood of Los Angeles, California, 1977

The Eameses patented the technology on their own, and as Demetrios stresses, “the military was absorbing the existing Eames knowledge into the war effort, not tasking them with inventing something.” The couple also created designs for better stretchers, pilot seats, and airplane parts.

The residence was redesigned by Charles and Ray Eames from the original 1945 plans, in 1948. Photographer Antonia Mulas

Following their work for the Navy came a succession of commercial contracts, but the most significant one arrived when the Herman Miller furniture company sought them out in 1946. It’s a relationship that remains today: Herman Miller, alongside Swiss company Vitra, would later own the exclusive manufacturing rights.

In addition to making movies and furniture, the busy couple also looked for solutions to meet the demands of the postwar housing shortage, a problem that predated the Great Depression but became a crisis with the return of massive numbers of World War II veterans and shortages of construction materials. A project sponsored by Arts and Architecture magazine sought designers to create prototypes as potential solutions. As part of the project, Charles co-designed Case Study House No. 8. Built as the Eames’ personal home in 1949 in the middle of an olive and eucalyptus meadow in Southern California’s Pacific Palisades, the home featured two rectangular boxes, each 17 feet high, one for a dwelling, the other for an office studio.

Eames Molded Plywood Splints

“The Eames House” was made of readily available industrial materials: pre-fab steel windows, factory-standard glass, and even parts from a marine catalog for the stairway. Perched on a bluff, the house granted views of the Pacific Ocean, and the Eames lived there for the rest of their lives. Aspects of the home’s design became hallmarks of postwar modern architecture, and today, the Eames Foundation gives tours of the home.

Lucia Eames with her children, Byron, Llisa, Eames, Carla, and Lucia, in the Eames House stu- dio, celebrating the creation of the Eames Foundation to preserve the home (2004). Photographed by Ron Chernus

Charles Eames with his granddaughter, Llisa Demetrios

The Eameses reigned as the disruptors of their time. They never thought that making mass-market furniture, accessories, or toys would diminish their status or influence. Their mantra: “We wanted to make the best, for the most, for the least.”

By the 1950s, they’d nabbed the attention of corporate America. The Eames developed films and exhibitions to demystify computers for IBM. They also created the promotional films for Polaroid. Demetrios remembers seeing a prototype of the camera when he and his siblings skipped school one day to visit his grandparents in San Francisco. He recalls Charles’ impish grin when he surprised them by unveiling the futuristic device, and Demetrios was amazed to see a snapshot of himself develop in his own hands. “I remember taking the picture to school, and no one would believe me until years later when the camera came on the market,” he says.

Eames Tandem Sling Seating, Dulles Airport in Washington, D.C., 1963

By 1973, the firm landed the commission for the exhibition The World of Franklin and Jefferson, which explored the connections between Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson and their impact on America’s independence. The massive traveling exhibit was praised overseas, but criticized at home for having too much information. Nonetheless, hundreds of thousands attended, and the couple gained even more notoriety. The project represented the Eameses final exhibition before Charles died suddenly on August 21, 1978, of a heart attack. Ray died exactly a decade later on the same day.

In its heyday, Eames Office was unlike any other space. The prolific three-ring circus of creation was filled with saltwater fish tanks, movie cameras, cases of sea shells and minerals, toy trains, and flood lights, to name a few. It was clear that Charles and Ray taught the staff to see the world differently.

“I will never forget seeing Charles take a photo of a small bouquet of flowers, and watching him bob up and down and moving all around. He easily shot an entire roll of film for that tiny bouquet,” says Carla, the Eames’ eldest grandchild. “It’s all about careful looking and considered thought.”

No Comments