11 Sep Perspective: Pop Goes the West

An Andy Warhol image of Elvis Presley, like the artist’s paintings of Marilyn Monroe, is pure Americana, a mirror reflecting early 1960s culture and its fascination with celebrity. Elvis as a singing teen heartthrob, a beach-scene matinee idol, is double Americana. But Warhol added another layer to the mix. In 1963, he gave us Elvis the gunslinger, based on a publicity still from the film “Flaming Star.” In true Warhol style, the artist tapped into another powerful part of the public psyche — the pervasive pull of the mythological American West. “It was triple Americana,” says Seth Hopkins, executive director of the Booth Western Art Museum in Cartersville, Georgia.

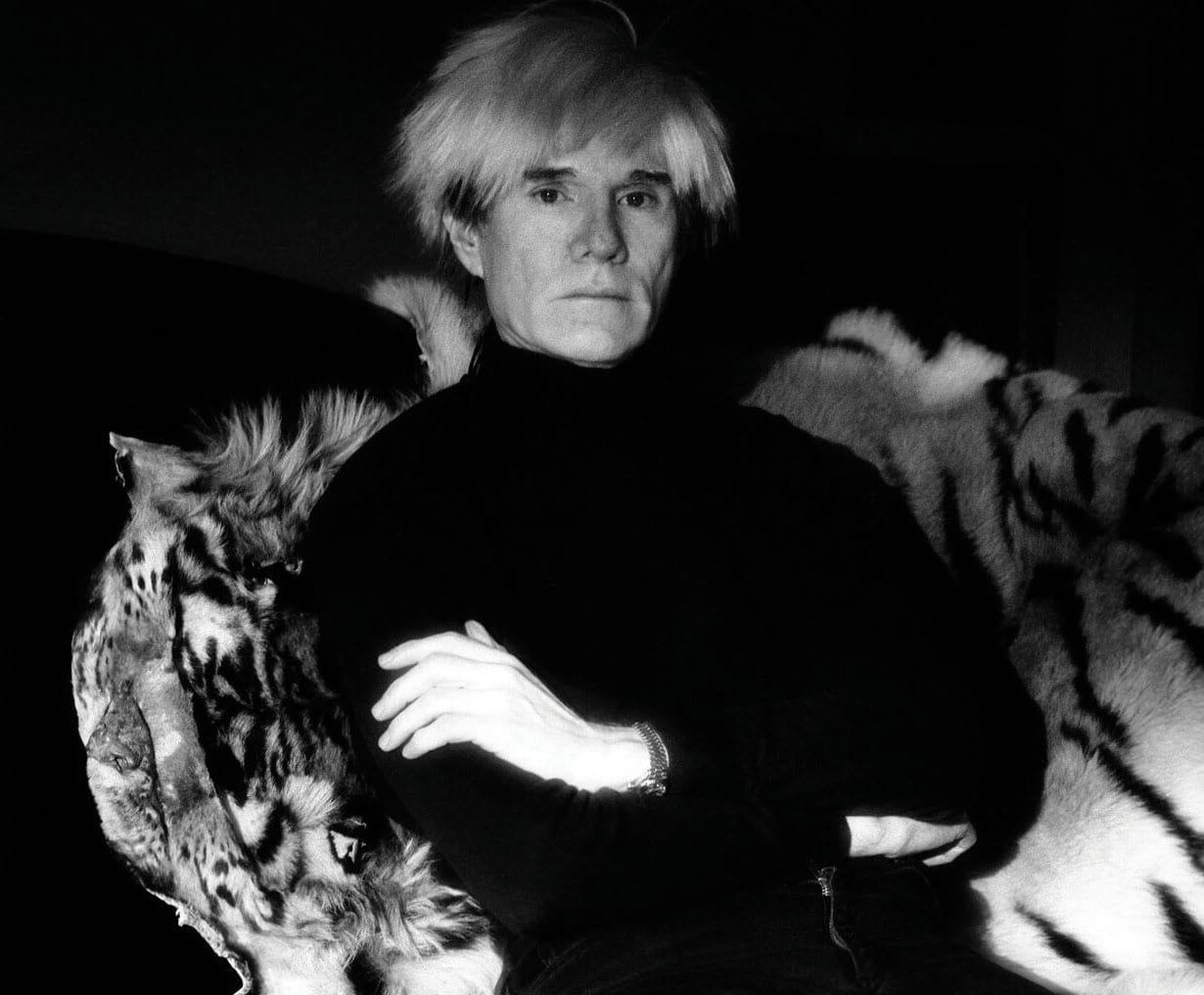

Andy Warhol | Jeannette Montgomery Barron | 1985 | Pigment Print | Courtesy of Jackson Fine Art

Warhol’s interest in the West and the region’s influence on his life and art are among the least-known aspects of an artist who masterfully generated buzz, while also presenting himself as a mystery, a myth of his own making. Warhol and the West, a traveling exhibition running through December 31 at the Booth, brings together artworks and objects supported by new scholarship that examines this relationship.

The exhibition was co-curated by Hopkins along with Faith Brower, Haub Curator of Western American Art at the Tacoma Art Museum in Washington, and Michael R. Grauer, McCasland Chair of Cowboy Culture and Curator of Cowboy Collections and Western Art at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. Developed by the three museums, Warhol and the West travels to Oklahoma City, January 31 to May 10, 2020, and opens July 1, 2020, in Tacoma. Among the show’s more than 100 items are 20-plus significant artworks and dozens of objects, including photographs, manuscripts, clips of films by Warhol, his cowboy boots, and source materials related to his art.

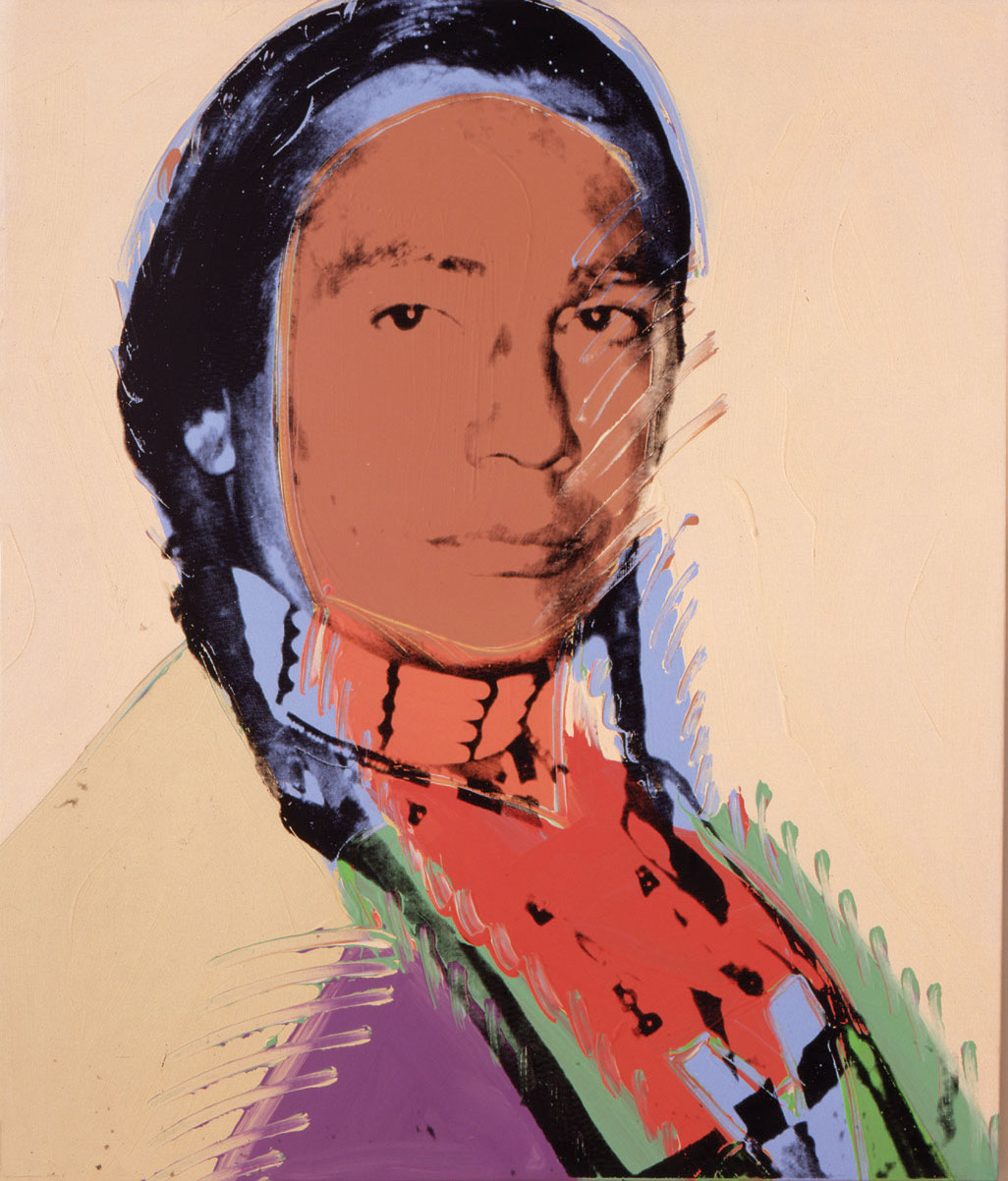

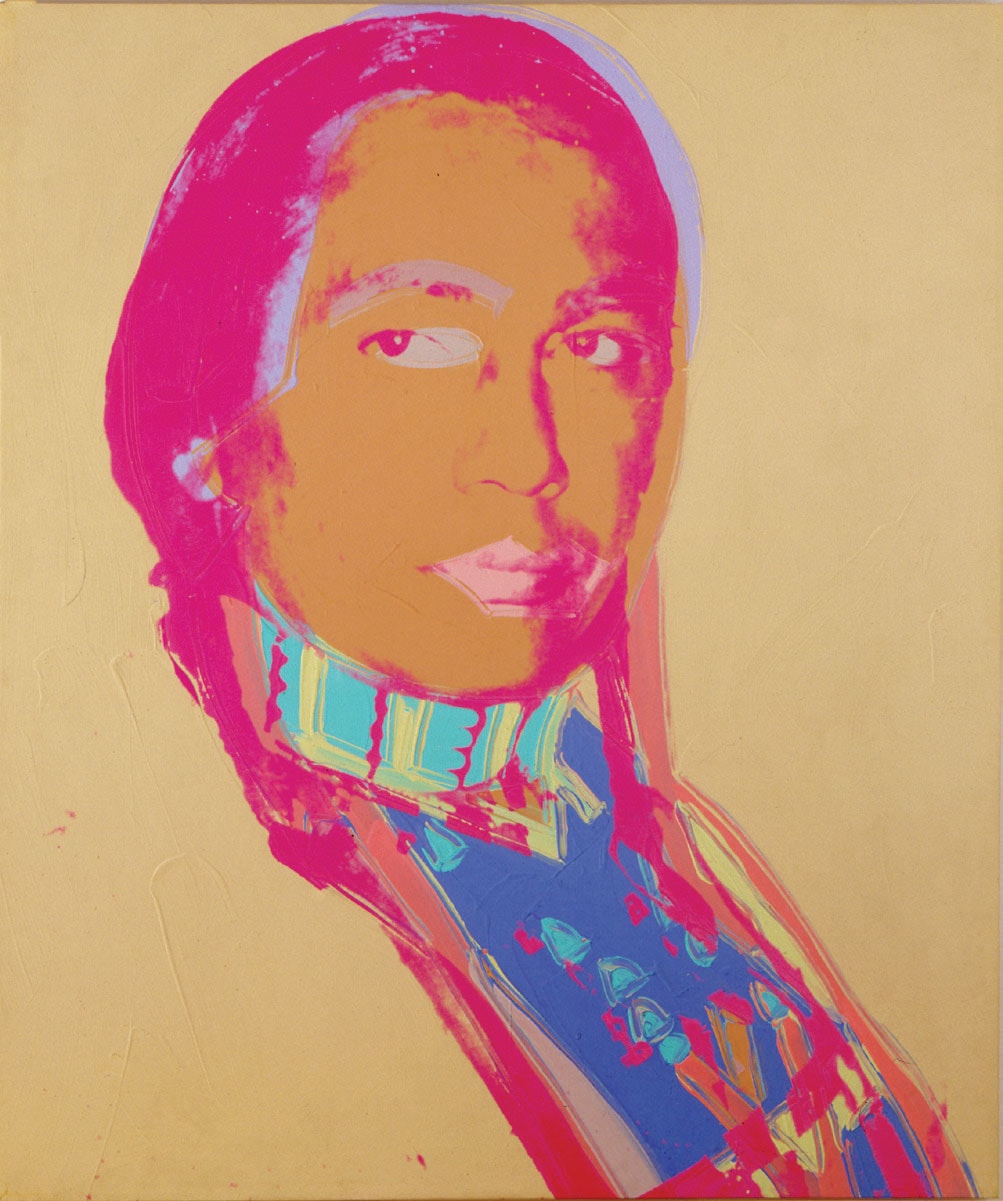

The American Indian (Russell Means) | 1976 | Acrylic and Silkscreen Ink on Linen | 50 x 42 inches | The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding collection, contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., 1998.1.211 (left) and 1998.1.212 (right), ©2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

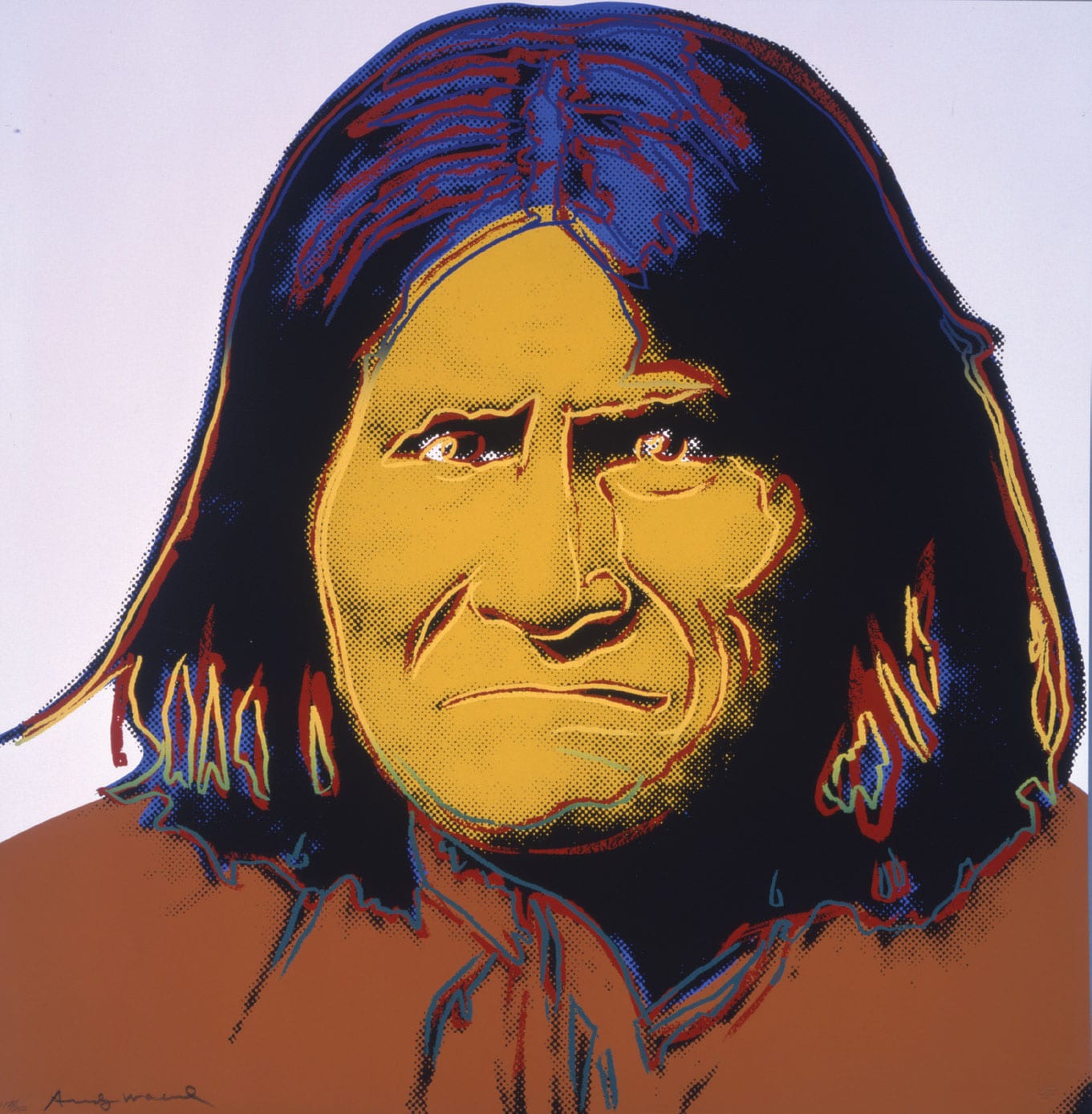

The capstone of the exhibit is Cowboys and Indians, a 10-print suite of 36-by-36-inch screenprints featuring iconic Western figures and Native American subjects and artifacts. Completed in 1986, it was Warhol’s last major project before his death, from cardiac arrhythmia following gallbladder surgery, at age 58. It was this portfolio, and its seemingly anomalous place in the Booth collection, that set Hopkins on the scholarly trail of Warhol’s connection with the West, ultimately leading to this show.

When Hopkins joined the Booth as the director in 2000, he was pondering research options related to an art history and museum studies master’s degree at the University of Oklahoma. Surveying the museum’s collection — mostly representational painting and sculpture of Western subjects, primarily by living artists — he came across a set of Warhol’s Cowboys and Indians serigraphs. Both the artist and the prints themselves, in their jangly pop colors and characteristic Warhol style, seemed out of place. “I needed to know: Did this come out of nowhere for Andy, or had he been interested in the West all along?” Hopkins says.

Cowboys and Indians: Annie Oakley | 1986 | Screenprint on Lenox Museum Board | Edition 55/250 | 36 x 36 inches | Collection of the Booth Western Art Museum ©2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

He spent the next nearly 15 years (and counting) ferreting out answers to this question, which became his 2005 master’s thesis and a personal and professional quest. A few years ago, he began developing the exhibit, although his research continues. During a Booth-related excursion in New Mexico early this summer, Hopkins spent time in Taos hoping to corroborate accounts of Warhol’s activities there. As with much of the lore, some stories are too slippery to pin down, he says. Other aspects of Warhol’s life are known, however, and when pieced together they reveal what Hopkins and his colleagues see as the artist’s lifelong Western-facing gaze.

Warhol was born in 1928 and raised in Pittsburgh by working-class immigrant parents from Austria-Hungary. As a boy, like so many of his era, he loved Saturday morning Westerns at the movies. He kept a scrapbook of celebrity-related promotional mini-posters “that he probably begged from the theater owners,” Hopkins says. Among his favorite Western stars were Roy Rogers and Gene Autry. (His Roy Rogers alarm clock is among the objects in Warhol and the West.)

Endangered Species: Bighorn Ram | 1983 | Screenprint on Lenox Museum Board | 38 x 38 inches | Artist’s Proof 21/30 | The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding collection, contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., 998.1.2466.10, ©2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

When Andy was in third grade he contracted Sydenham’s chorea, also called Saint Vitus’s Dance, which contributed to his albino-ish look as an adult. Confined to bed for stretches at a time, he drew. He hung movie star pictures on his bedroom walls and likely played cowboys and Indians with a toy cap gun given to him by his doctor.

Following his 1949 graduation with a BFA in pictorial design from Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) in Pittsburgh, Warhol moved to New York City. He started his career in advertising art and by the mid-1950s was shifting into his signature pop style, leading to quintessential images of Brillo boxes and Campbell’s soup cans. Although he based his career in New York, since boyhood he dreamed about places he’d never been. In his diaries and later his book, America, he specifically mentioned Texas, professing his admiration for Texans because when they had money, they “just went out and did what they’d always wanted to do with it.” When asked where an Andy Warhol museum should be located, if there were one, the artist’s response was Houston, and that it should look like a Neiman Marcus store.

Cowboys and Indians: Geronimo | 1986 | Screenprint on Lenox, Museum Board | Edition 94/250 | 36 x 36 inches | Collection of the Booth Western Art Museum, ©2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Cowboys and Indians: Geronimo | 1986 | Screenprint on Lenox, Museum Board | Edition 94/250 | 36 x 36 inches | Collection of the Booth Western Art Museum, ©2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Along with Texas, where he often traveled in connection with commissioned portraits and gallery shows of his work, much of Warhol’s time in the West was spent in Los Angeles, soaking up and reflecting Hollywood’s glitz. He also owned property near Aspen, Colorado, and filmed “Lonesome Cowboys” in Arizona, partly at the Western movie set Old Tucson. Hopkins has uncovered accounts of Warhol drinking with actor Dennis Hopper and the artist R.C. Gorman in Taos, and an uncorroborated report that Warhol and Hopper owned an American Indian art store together in Taos.

Hopper is among numerous Western-connected figures who served as subjects for Warhol portraits. Others included Gorman, American Indian artist Fritz Scholder, activist Russell Means, and Georgia O’Keeffe, whom he visited in New Mexico when she was 92. Hopkins describes Warhol’s O’Keeffe portrait — a silkscreen finished in diamond dust with some prints incorporating gold pigment — as “one of his most haunting and stunning images, almost as if she’s staring through you.”

Cowboys and Indians: Kachina Dolls | 1986 | Screenprint on Lenox Museum Board | Edition 55/250 | 36 x 36 inches Collection of the Booth Western Art Museum, ©2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NewYork

Although it is unclear whether Warhol purchased art in Taos, he was known to be an obsessive shopper, amassing an enormous collection of Western and Native American art and artifacts over the years. Some were by renowned artists, including Western-themed paintings by Albert Bierstadt, Maxfield Parrish, and 300 Edward S. Curtis photographs. Other pieces were apparently inexpensive, many purchased at a store that sold American Indian artifacts just around the corner from his New York City home. After his death, a Sotheby’s liquidation auction of his collections devoted almost a full day to his more than 650 pieces of American Indian art. Warhol also left 27 pairs of cowboy boots, about half of which were paint-splattered, indicating he wore them in the studio.

Aside from his indelible influence on American art in general, Warhol left his mark on many contemporary Western and Native American painters. He “opened a door that made it relevant for art to engage with popular culture in new ways,” notes Brower in an essay in the exhibition catalogue. “Inside this door, we find Western and Native artists creating spaces in which to reflect on, interpret, and even challenge contemporary experiences and values.” The most obvious of these artists is Billy Schenck, who in the mid-1960s and early ’70s spent time in Warhol’s circle in New York City. Among other Western painters impacted by his approach are Duke Beardsley, Maura Allen, and Tom Gilleon; Native American artists responding to Warhol’s legacy include David Bradley, Stanley Natchez, and Frank Buffalo Hyde.

Howdy Doody | 1980 | Polaroid Polacolor 2 | 4.25 x 33.375 inches | The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., 2001.2.1525, ©2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“Pop art was hailed during its heyday as purely American — notwithstanding that the term and the movement originated in England,” Hopkins writes. “Warhol regularly told interviewers that he was as American as they come, and few things are more uniquely American than the West. … His work is a surface, as he suggests: a self-reflecting mirror that looks wryly at American culture — the good, the bad, and the ugly. But despite Warhol’s statement, his art goes deeper; it is nuanced and layered in complexities.” An example of this is Warhol’s series of portraits of Russell Means — who was prominent in protests and occupations against the U.S. government on behalf of American Indians — produced in 1976 during the country’s bicentennial year. The artist’s decision to paint Means came after he asked a Los Angeles gallerist for the name of the most representative figure in the American Indian sovereignty movement, Hopkins says.

In addition, the Cowboys and Indians suite contains an image of the Buffalo nickel in which the American Indian pictured stares at the word liberty. “It’s ironic, and Warhol brings it up a notch by making the word more prominent in the print. Coincidence? I think not,” Hopkins says.

Endangered Species: Bald Eagle | 1983 | Screenprint on Lenox Museum Board | 38 x 38 inches | Artist’s Proof 21/30 | The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding collection, contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., 1998.1.2466.4, ©2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Questions of Native American identity and place in American culture remain today, as do the complexities of myth and reality in the West, and society’s fixation on celebrity. Just as an enigmatic artist once showed America’s surface qualities to itself, historical distance and new scholarship now turn the mirror back on the artist and the West. A generation after Warhol, Hopkins says, “It’s time to take a fresh look.”

No Comments