08 Nov Lee Andre

IN 1999, LEE ANDRE TRAVELED TO KOREA, the country from which she’d been adopted at age 5 by a family from Minneapolis. She’d grown up as an American, discovered a proclivity for art at an early age, and went on to study fine art at the University of Washington. After college, Andre built a decorative painting business in Seattle and was making a living, but she wasn’t painting her vision. So, why not put her business on hold for a few weeks, hop on a plane, and see this place she was from but scarcely knew?

Plains Bison | Charcoal on Panel| 36 x 45 inches | 2019

As fate would have it, while there she met a dashing Brit, Brian Pearson-Fry, who was working in Seoul. A whirlwind romance ensued, and soon enough, they married. Andre sold her business, and for the next 15 years, the couple lived abroad in Abu Dhabi, Bangkok, Qatar, Oman, and other major cities.

The years slipped by; Andre’s life given over to her husband’s. Art, she decided, was too much of a commitment if done right, so she let that aspect of herself lay dormant. The plan had always been to start painting again when Brian retired. Life, however, took a very different turn when, in 2015, Brian was diagnosed with terminal cancer and died the following year.

Alone, Andre immersed herself in painting, allowing this singular focus to carry her along a river of emotion. “It’s gut-wrenching, the loss,” she says. “My whole identity was wrapped around my husband’s lifestyle. I looked at this pile of suitcases and realized I’d lost my life. I had to figure out my identity.”

And so, at age 49, Andre started over.

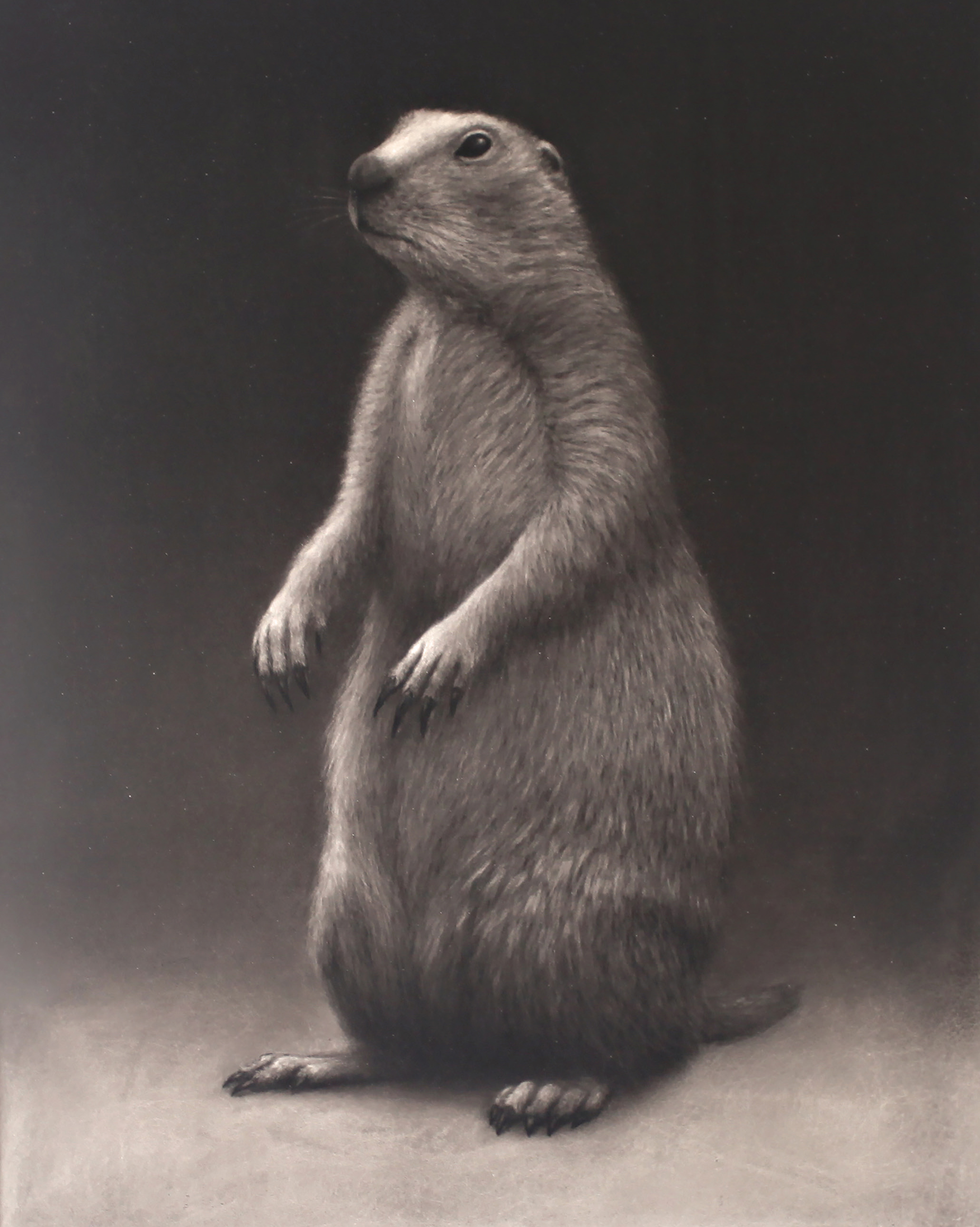

Prairie Dog | Charcoal on Panel| 11 x 14 inches | 2017

Drawing with charcoal was a journey back to the foundations she explored in college. But this time, she decided to experiment with an idea she’d thought up back then but hadn’t pursued: drawing with charcoal on a plaster-like surface. Her thinking was to see what happened when powdery charcoal blended with a soft, mutable substrate. It took considerable time and effort, but she finally concocted a custom surface that achieved her purpose. As for the subject matter, she’d studied abstraction in college, but now wildlife offered more intrigue for two reasons: it was an endless subject, and it holds opportunities for deep emotional connections.

Of the substrate she developed, the good news was that finished drawings could be sealed like paintings, and thus didn’t require glass covering. The downside: her custom-made surfaces required a week to create with no guarantees they would work. Her early attempts were, as she called it, fickle. “With charcoal, you’re in filth all day. Each stage requires a lot of patience because, if it doesn’t work, you have to throw it away.” Which is what happened when beads of sweat dropped onto a finished but unsealed drawing; nothing she tried would get it out, it was destroyed, a total loss.

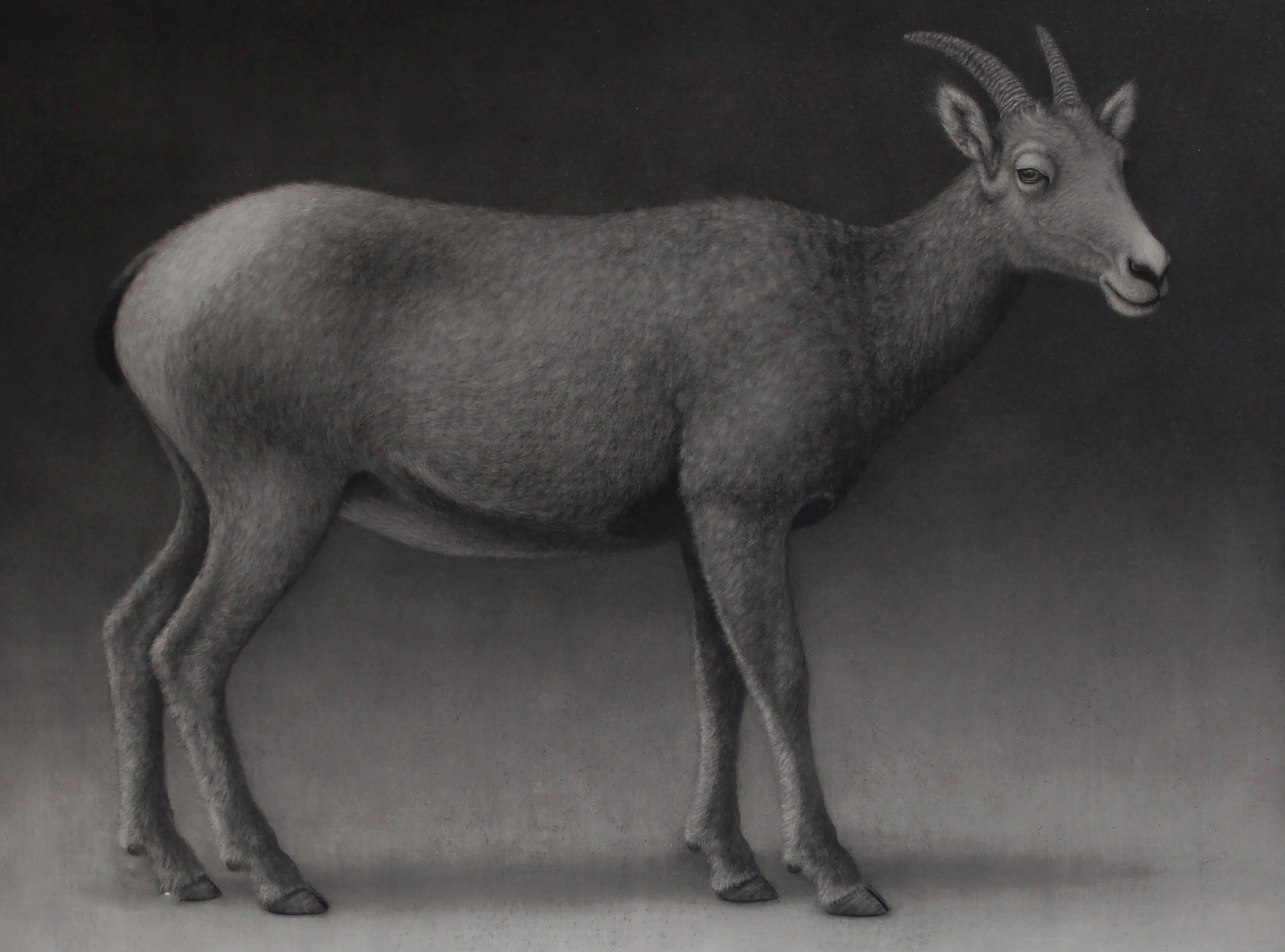

Bighorn Ewe | Charcoal on Panel | 36 x 45 inches | 2019

Ultimately, the tactile sensation of charcoal digging and blending into the plaster substrate has given her a way to echo the slightly surreal, haunting feeling of daguerreotypes. “I remember seeing old photos at thrift stores, anonymous photos that just wound up there. I think the connection I made had something to do with loss,” she says, explaining why she stays with black and white compositions,

eschewing color. “And they are calming. I think there’s a collective longing for stillness in our lives. I wanted to address that a little bit in what I do.”

Victoria Haven, an artist and long-time friend from college, noted Andre’s capacity to articulate emotional and psychological depth in her work using simple materials. “The visual rigor, evident in her earlier work, feels more finely tuned in her current drawings based on animals,” Haven says, adding that Andre’s “attention to detail and exquisite mark-making expands beyond the external work of forms and surfaces to encompass the complex interior life of her earthly subjects.”

For each work, Andre references upwards of 40 images to get a feel for the animal, but she never copies any particular image. “My process is that I use references to see how the animal functions and moves. Often, I have photos up, but it’s never just one or two, it’s many, many images.”

Karanina Madden-Krall, aviation art collections manager at the Albuquerque International Sunport, noted that Andre’s attention to detail is like that of a biologist, almost scientific. “But with a softness,” she adds. “Lee brings a real emotional aspect to these animals in a way that makes you appreciate this beautiful earth and all of its creatures.”

Opossum | Charcoal on Panel | 15 x 20 inches | 2019

Larger issues are always at play in Andre’s work. For example, the painting Plight of the Key Deer began as a study of an endangered species but morphed into something more. “When I put the crows into the composition,” she explains, “they were design elements, but they are also harbingers of death. It reminded me of all that I was going through with the loss of my husband. I started thinking of how innocent creatures are in the face of death. We can’t know what fate will bring us; we’re oblivious to the amount of time we have.”

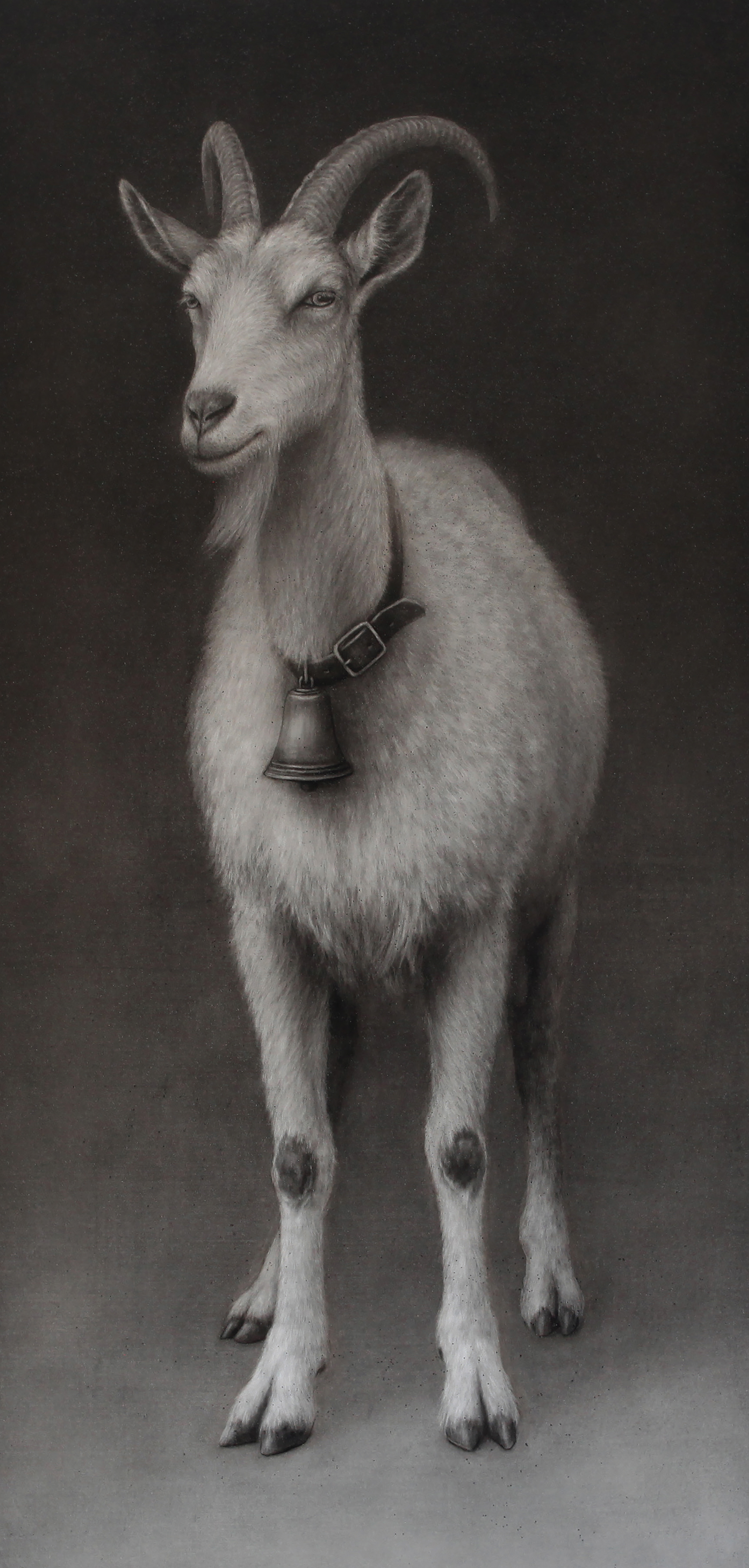

Nanny Goat | Charcoal on Panel| 21 x 41 inches | 2019

Fellow artist William Haskell first saw Andre’s work two years ago and was immediately drawn to her “soulful elegance.” As he explains it, “Her paintings are both captivating and understated, obviously a self-portrait of the artist. I think what you have seen so far is the tip of the iceberg.”

Andre’s days are solitary by choice, but lately she’s been thinking of moving to Santa Fe to be closer to her sister and the art community out West, which seems to offer a sense of renewal. Wherever she lands, her creations will always carry a tiny piece of her husband and their shared past: she seals each drawing with a red stamp, her name in Korean, and the first gift Brian gave her.

“When I talked about my work being about loss,” Andre says, “I suppose it’s really about love also. I don’t think loss happens unless there was love in the first place.”

No Comments