08 Jul Rendering: Reading The Landscape

Discovering landscape architecture at Texas A&M University was hardly David Hocker’s aha moment. For a kid who loved the outdoors, made pocket money doing yard work, and had some great art teachers in high school, it simply seemed logical.

“It was kind of a gut feeling that this would be of interest to me,” he says. “Just going into architecture didn’t interest me. I wasn’t into confined spaces. To me, it’s a bigger idea of dealing with natural systems and the spaces between, and the peeling back of sites through design.”

The Lexington entry pond is also lined in tiles by Cerámica Suro. The natural textures of lily pads, trees, and rocks contrast with the elegant steel doors and glass.

That aha moment came later, during the fourth year of his five-year education. Texas A&M offers a study abroad program housed in a 500-year-old convent in Castiglion Fiorentino in Tuscany. It was here that the founder of Hocker Design Group had his eyes peeled open by the patterns of the landscape: the olive groves, the rolling hills and agricultural overlay, the Italian gardens and historic urban design.

“It changed my outlook on life, my design sensibilities, and my love for the profession, for all things design and construction related,” he explains. Hocker also met his wife, Gisela, there, and they return to the region two or three times a year. “That’s my recharge,” he adds.

- Agave and yucca soften the orthogonal lines on a second-floor terrace.

- Abstract, linear, grassy terraces frame a house designed by Alterstudio of Austin, Texas.

- Hocker Design Group creates outdoor spaces that focus on texture and scale.

The Italian influence is not immediately discernible in the firm’s modern and arrestingly original projects. Their elegant minimalism seems far removed from the Tuscan countryside and traditional Italian gardens. But look closer, and you start to see the way Hocker has absorbed those vistas and outdoor spaces, re-envisioning them through an energetic, contemporary eye, and producing designs with a bold signature that includes clean, orthogonal lines softened by plantings and grasses.

A steel fence separates the soft zoysia lawn from a plot of hardy Texas wildflowers.

“I can’t speak for the whole profession,” he says, “but I do view landscape architecture as a historic tradition, turning design, sculpture, and art into a technical profession that has both an artistic, creative, right-side-of-the-brain component, but also has to be exacting and technically competent to manifest these ideas into something that can be used and enjoyed; something that will continue to develop.”

After graduating, Hocker spent a few years at a Dallas firm before, at 28, a friend, who had already opened his own architecture firm, encouraged him to set up shop at a desk there with him. Between the projects Hocker brought along and collaborations with his architect friend, he quickly built a portfolio, and the company grew from a staff of one to 10.

- Cedar Creek’s five acres are shaded by elm, oak, and pine trees that soften the modern lines of the lakeside house by Wernerfield Architecture Design.

- A wall of Oklahoma silvermist boulders provides continuity in the landscape design.

- A sunken seating area and fire pit draw attention from the lake to the property, where grassy steel-lined steps descend to a permeable gravel floor that’s guarded from the elements by a wall of Oklahoma silvermist boulders. The teak chairs are by David Sutherland.

Something Hocker is adamant about is joining a project from day one — or even before. He regards the architect, the engineers, the construction companies, and his firm as one team aiming at the highest level of design.

“We’re good collaborators,” he says. “We still get solicitations like, ‘Oh we’re at this stage of design, and we’d like to bring you on.’ But in reality, what are we going to offer at that point? We bring a lot of value to the conceptual part of the project, especially when we’re dealing with sensitive sites.”

A screen lined with evergreen wisteria blocks off the tennis court.

When he joins the process early on, he adds, “it’s these charettes or voluble discussions that help influence where the house sits on the site, and what sensitivities on the site to avoid — how do we work around this existing tree? Then you get to the level of transitions: what happens on the thresholds, where the houses’ focal points are. When a team is very collaborative on a project, those are the best projects, because you can’t tell where one profession begins or ends.”

For Hocker, color takes a back seat to texture and scale. He prefers a more muted palette, and for flowers, he leans toward native plants that provide seasonal pops of color but with generally more subtle, smaller blooms. Tropical floral displays are not for him.

Sonoma is a prefabricated house designed by Alchemy Architects of Saint Paul, Minnesota, for architect B.J. Siegel, who wanted minimum interference on the site. Hocker replanted the hillside with native grasses.

“That seems to me to hurt the eye. It’s garish and out of place, especially in Texas, where, as the summer wears on, the lighting gets even harsher,” he says, adding “I build textures into the materials as well. When you look at a lot of our work, it’s very honest; it’s usually a lot of crushed aggregate, concrete, stone, wood — honest, traditional materials.”

He’s drawn to other traditional elements as well, like cobblestone, but reinterprets them in a clean, more angular, and modern aesthetic, softened by plantings.

Rather than interrupt the house’s sweeping view over the Matanzas Creek Valley, Hocker placed the entry court, pool, and outdoor living room at the rear.

When a site is challenging, with existing trees or what Hocker calls tabula rasa — a flat, treeless site with little interest — the viewer’s perception is key. In a project called Lexington, a flat site was sculpted with angular, concrete-edged terraces of native grasses that descend into a dark, blue-tiled pool with a cobblestone lounging area. The front entrance is characterized by hillocks of rocks and boulders rising from the cobblestones, all softened by native plants. The perception of the landscape changes radically, and no one would guess that the multi-leveled, sculpted garden was once a charmless suburban lot. “That was one where every decision was a collaborative effort,” he says.

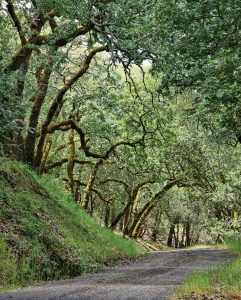

The winding gravel road leading up to Sonoma is lined with oaks and opens up to meadows and ferns.

When it comes to pools, Hocker prefers that they blend in. If he could always have his way, they’d have no wide surrounds and would all have darker finishes. “They’re more about being water features than a typical swimming pool,” he explains. “Having a darker finish allows them to become something that’s animated by the sky or the lighting at night, by the moonlight and stars.”

When possible, the pools and water features he designs are biologically filtered. “They have fish and plant material, and they’re allowed to create an algae buildup on their surfaces but have crystal-clear water,” he says. “Again, it’s part of the axial of formal design, but then allowing nature to erode away the harder lines.”

Though the primary trees around the Sonoma home are coast live oaks, fruit and olive trees were added, along with dwarf fescue, rosemary, and agave. The pool, outdoor grill, and patio area connect the main house to the compact guest house.

At the award-winning home Cedar Creek, Hocker’s design touched nearly every part of the seven-acre lakeside family compound. The site had a lot of pine trees, but little else of interest. Since all the views naturally turned toward the lake, he challenged the quotidian by creating destination areas all across the property, from a sunken fire pit to a bocce ball court. The water features are fed by condensation from the air conditioning as well as rainwater, and an allée of pine trees was planted with secondary trees that will take over when the older trees die.

“We try to expose people to more drought-tolerant species, as well as things people generally think of getting rid of, like prickly pear or mesquite trees,” he says. “Everybody likes a wildflower meadow for that two weeks out of a year, but then they call and want to know, ‘Why does this look dead?’”

Dramatic steel stairs provide views in a transitional area.

At a home called Sonoma, on a hilltop in California wine country, native grasses sweep up against the stunning views across the valley. Rather than siting the pool between the house and the view, he placed the motor court and outdoor features to the rear. Here, one end of the dark-lined pool blends into the vegetation, while the other end connects with a tree-shaded lounge area.

This year, Hocker Design Group is celebrating its 15th anniversary with the September release of a monogram from Monacelli Press, Hocker: 2005–2020 Landscapes. Hocker already works in California, Oklahoma, and Texas, but he sees the firm expanding into different areas in the future. One thing he doesn’t want is an unwieldy, impersonally large firm. As it is, the staff at Hocker Design Group all have the satisfaction of seeing the projects they’re working on from conception to finish.

| The native grasses, which flow right up to the primary residence and guest house, are trimmed during the fire season.

“It doesn’t interest me to be just feeding the machine and cranking out work in volume,” Hocker says. And this also translates into the passion that’s evident in every finished project.

No Comments