10 Sep Perspective: Abstract In Nature

The last time Mara Williams, Chief Curator of the Brattleboro Museum & Art Center, saw Emily Mason, it was about a week before the artist’s death in December 2019. At the time, Mason was in rural Vermont where, for more than 50 years, she spent summers with her husband, painter Wolf Kahn. Normally they returned to their New York City apartment and studios in the fall. But that year, the couple decided to stay at their hilltop home near Brattleboro after Mason declined further treatment for the cancer she’d been diagnosed with a few months earlier.

At 87, the petite, willowy artist was perched bird-like on the edge of a living room chair, legs crossed gracefully at the ankles. “She had that luminous look, her eyes sparkling beautifully,” Williams recalls. Someone asked Mason what it was like for her to be in Vermont that time of year. “Oh, the fall’s been glorious, the colors, the changing leaves,” she responded in her characteristically soft-spoken, delighted manner. Then she added: “My goodness, the landscape looks exactly like a Wolf Kahn painting!”

Artists Wolf Kahn and Emily Mason. Photo: Jeff Burkett

Mason and Kahn were both exceptionally gifted with color, yet expressed very different visions. They were enthusiastic champions of each other’s work for the 62 years of their married life. After an early period of painting with their backs to each other in a shared New York studio, they kept separate studios in Vermont and New York City, each artist working virtually every day until less than a week before their deaths. Kahn outlived his wife by four months, dying on March 15, 2020 at age 92.

Both painters were drawn to abstraction and inspired by the natural world. Kahn produced abstracted landscapes in oil and pastel, while Mason used color and intuition to create vibrant, lyrical works of pure abstraction. Williams remembers Kahn commenting with admiration — and perhaps a touch of awe — on his wife’s approach. “I hover on the edge of abstraction,” he said, “but I don’t have the courage to be a purely abstract artist.”

Over the decades, Kahn and Mason each gained critical acclaim and appreciative collectors, with representation in New York City and Santa Fe. Galleries in both cities, as well as the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, Connecticut, plan to honor the artists with memorial exhibitions in the coming months.

Emily Mason, Cold Spell | Oil on Canvas | 26 x 22 inches | 2016 | ©2020 Emily Mason Studio/ Estate of Emily Mason / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy LewAllen Galleries, NM and Miles McEnery Gallery, NY

Born in New York City in 1932, Mason grew up steeped in the art world, coming of age in the midst of Mid-century Modernism. Her mother, Alice Trumbull Mason — a descendant of John Trumbull, an American painter of the early independence period — is considered among the first American female abstract painters. A founding member of American Abstract Artists, she was a “den mother,” as Williams puts it, for a generation of abstract painters. She took her young daughter along to museum exhibitions, gallery shows, and visits to artists’ studios, including that of Robert Motherwell. “Emily talked about how profoundly she admired her mother, and how the life of an artist and a commitment to art-making was just so much a part of her own DNA,” Williams says.

After graduating from the High School of Music and Art in Manhattan, Mason studied at Bennington College in Vermont and, in 1955, earned a fine art degree from The Cooper Union in New York. At the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in Maine in the summer of 1952, a lecture by renowned textile artist Jack Lenor Larsen opened her eyes to the vast possibilities of color. In 1956, Mason traveled to Italy on a two-year Fulbright Scholarship to study at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Venice. There, in 1957, she married Kahn, whom she had met previously in New York. They returned to the city, and Mason began her painting career, enjoying her first solo show in 1960 at the Area Gallery in Manhattan.

Emily Mason, Wet Paint Spring | Oil on Canvas | 50 x 40 inches | 1963 | ©2020 Emily Mason Studio/ Estate of Emily Mason / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy LewAllen Galleries, NM and Miles McEnery Gallery, NY

Kahn arrived in New York City in 1940 as a boy of 13, sent from Germany to escape the Nazis. His parents and three siblings immigrated to America some years earlier, while at age 3, Kahn was taken in by his grandmother in Frankfurt. He began drawing as a very young child, and later took private art lessons. As World War II heated up, he was placed on a Kindertransport train organized to take Jewish children to safety. He was sent to England and then reunited with his family in New York, where he attended the High School of Music and Art in Manhattan and graduated in 1945.

After a stint in the Navy, Kahn’s focus returned to art. Under the GI Bill, he became a student of Abstract Expressionist painter Hans Hofmann, for whom he later served as a studio assistant. In 1950, Kahn entered the University of Chicago, earning a Bachelor of Arts in one year before returning to New York and making a full-time commitment to art. He explored pure abstraction while studying with Hofmann, then turned briefly in the 1950s to figurative work along with a group of other Mid-century Modernist painters who had re-embraced that genre.

Soon he developed what became his distinctive style: abstract landscapes depicted in layers of luminous color. “For Wolf, it was always a balancing act between some level of realism and conscious abstraction — that dangerous act was so exciting to him,” remarks Louis Newman, director of Modernism at LewAllen Galleries in Santa Fe. Newman brought Kahn on board at LewAllen a few years ago when the gallerist moved to Santa Fe. Prior to that, he represented Mason for some 20 years as a gallery director in New York City.

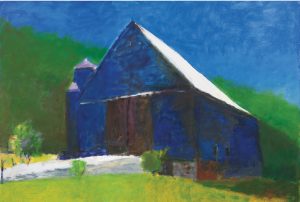

Wolf Kahn, Roston Barn | Oil on Canvas | 36 x 52 inches | 2004 | ©2020 Wolf Kahn / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

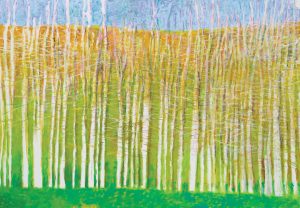

Williams also points to Kahn’s finely tuned sense of balance. The curator notes how his winter paintings in particular emphasize a strong verticality against the contours of the Vermont hills. This was part of what Mason was responding to when she likened the state’s fall and winter landscape to his work, Williams believes. “If you’re in Vermont all year, you can clearly see where his inspiration came from,” she says. “He was a magnificent colorist with a lot of daring, pushing it almost to the point where it will fall apart, but it doesn’t. The structural underpinning allows him to do that.”

While Mason’s paintings are entirely abstract, nature also held an important place in her life. She and her husband were passionate gardeners at their Vermont home, and Mason’s New York studio was filled with plants. Inspired by the poetry of her namesake Emily Dickinson, as well as by New England Transcendentalist writers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, she created delicately nuanced works that Newman describes as spiritual landscapes. “You can see forces of nature in her paintings: eddies or air currents. Or it’s as if you’re peering into the works from a distant vantage point,” he says.

Wolf Kahn, Large Tree Parade | Oil on Canvas | 64 x 90 inches | 2013 | ©2020 Wolf Kahn / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Mason produced such effects through a process that took place entirely in paint, without preconceived ideas or preliminary drawings. Beginning with the canvas on a flat surface, she poured layers of paint and tilted the canvas or moved the color around with rags and brushes. It was an improvisational call-and-response dance that combined years of experience with the conscious intention of keeping her mind out of the way. And it was a joyous activity, reflecting an open, curious spirit and an extraordinary level of visual and aesthetic awareness, Williams says. “She approached everything with an exploration of creativity. She delighted and reveled in it.”

Part of Mason’s legacy lies in what she gave to hundreds of painting students during her more than 30 years of teaching at Hunter College in New York City. Above all, she showed them how to pay attention to their own perceptions and unlock authentic creativity, rather than imitate her work, Williams says. Kahn will also be remembered as an effective and engaging teacher, leading dozens of workshops over the decades.

With a shock of white hair in his later years and cornflower blue eyes, Kahn was a larger-than-life character and a captivating raconteur. “He was generous, kind, funny, and loved reciting poems and telling stories,” says Miles McEnery, owner of Miles McEnery Gallery in New York City, which represented the painter for more than 20 years. As an art couple, McEnery says, Kahn and Mason “complemented each other beautifully. They pushed and pulled each other along.”

Emily Mason, March is Heard | Oil on Canvas | 60 x 54 inches | 1998 | ©2020 Emily Mason Studio/ Estate of Emily Mason / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy LewAllen Galleries, NM and Miles McEnery Gallery, NY

In recent years, Kahn experienced progressively limited peripheral vision as a result of macular degeneration. Yet he not only continued to paint but discovered ways of compensating for his changing eyesight. Whereas most of his career saw him applying oils in scruffy marks with cheap, stiff-bristled brushes, he was able to reproduce his signature works in layers of oil pastel. “He found a way to continue to make paintings that are really satisfying and complete works right up to the end,” Williams says. She adds that he could “coax the subtlest whisper or the most bombastic oratory out of his chromatic combinations.” Meanwhile, Mason’s artistic expression became ever more sensitively distilled. “Her relationship to the world of vision and sensation was almost as delicate as the finest barometer in the world,” Williams says.

Over their careers, the work of both artists enjoyed a place in the permanent collections of major museums. For Kahn, these include The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Mason’s art is in the National Academy Museum & School in New York City and the Cleveland Museum of Art, among others, and both are represented at the Brattleboro Museum & Art Center.

Williams believes that during their lifetimes the two were somewhat overlooked as serious contemporary American artists, perhaps in part because of the pure aesthetic beauty of their art. But as art historians and critics delve more deeply into their legacies and bodies of work, she sees that changing. “When the big sweep and nuanced picture is written, I think they will figure fairly prominently in it,” she says.

Editor’s Note: Upcoming exhibitions featuring works by Mason and Kahn include Emily Mason: Memorial Exhibition at LewAllen Galleries in Santa Fe, September 4 – October 17; She Sweeps with Many-Colored Brooms: Paintings and Prints by Emily Mason at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, Connecticut, September 26 – January 3, 2021; Emily Mason Memorial Exhibition (21st Street location) and Wolf Kahn Memorial Exhibition (22nd Street location) at Miles McEnery Gallery, New York City, concurrent shows January 7 – February 12, 2021.

No Comments