10 Sep Captured Beauty

Human skulls are not new subject matter for Daniel Sprick’s paintings, but the cranium took on a more macabre significance during the coronavirus pandemic when the artist created a new series of ethereal interiors, titled Shelter-In-Place.

“‘Shelter-in-place’ was the term we were hearing toward the beginning, and then it was ‘quarantine,’” says the Denver, Colorado-based painter who is revered for his realistic portraits, surrealistic landscapes, and still life works.

“We got the order right around March 15, but I didn’t have to shelter-in-place because there was no prohibition about bicycling or driving cars, so I could get back and forth from the studio,” Sprick says, adding that prior to Colorado’s COVID-19 stay-at-home order, he had painted a few interiors of his high-rise apartment. At home, he had already set up easels and was equipped with brushes and paints, so he opted to hunker down along with most of the world.

Bicycle | Oil | 12 x 9 inches

“There was no reason why I couldn’t work at the studio. No reason at all. I own it alone and work alone and wouldn’t come into contact with anyone,” says Sprick. But the artist’s sense of social justice compounded his compassion and sent him into self-quarantine.

“I decided to stay at home, and I was trying to figure [it] out myself, asking, ‘Why are you staying home?’ On some level, I was doing it out of solidarity for everyone suddenly stuck at home — if lucky enough to have a home to be stuck in,” he says. “To get the order to shelter-in-place when you don’t have a place, my God!”

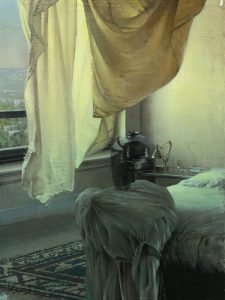

The period of self-quarantine inspired the series, which Sprick painted in his 16th-floor apartment near City Park in Denver. Shelter-In-Place includes 11 oil on plywood or Masonite works ranging in size from 9 by 12 to 16 by 20 inches. Sprick painted the series in an elegantly neutral palette of mostly umbers, siennas, and a wide range of whites. The paintings glow with natural light and radiant highlights in Sprick’s signature pale yellows — the ghastly near-white on the bleached skull, the soft sheen of off-white leather furniture, the pages of stacked books, or bed sheets line-drying like misplaced clipper ship sails.

Laundry | Oil | 16 x 12 inches

Sprick’s luminous new paintings present not only the artist’s technical brilliance with chiaroscuro, but they also testify to bright points during dark times. And for Sprick, the skull represents life as much as it does death.

“My father had that skull,” says Sprick. “It was one we had once in our house because my dad made false teeth and used that skull to study dental occlusion,” Sprick says. “I got so used to seeing it and didn’t think about death. I just saw it as natural. Beautiful.”

Sprick collected four additional skulls that he used as subject matter in the series. “Real human skulls,” the artist says. “Skulls, mortality; it’s a perennial subject of mine. The shape and color. And as a metaphor, the skull is interesting. I could substitute a squash or cabbage, and it might be the right size, but it’s not as interesting. For me, for composition, there’s not anything else as equally interesting.”

Sprick’s work has garnered significant interest from the Denver Art Museum (DAM), where the painter has had two solo shows and also a gallery installation devoted to his process that was exhibited in the Hamilton Building for 10 years. Timothy James Standring, the Gates Family Foundation curator of painting and sculpture at DAM, commented on Sprick’s new paintings: “His recent works record the quiet moments of his recent lockdown [and] appeal to us through his stunningly beautiful treatment of natural light that partially floods these interiors. [The paintings] conjure up memories of the mundane — door frames and door knobs, bicycle hardware, a fingernail clipper, and an electric toothbrush — as well as the worldly, such as a Ming vase

View with Bicycle | Oil | 10 x 20 inches

In these pandemic paintings, Sprick also included ancient Egyptian funerary figurines known as ushabtis. “I’ve collected them. They were entombed with the deceased around 2000 BCE and removed from those tombs by a British archaeologist in the 20th century,” says Sprick. “One is a ceramic piece but painted as a textile. There’s an inconspicuous death undercurrent, but most viewers won’t notice.”

Despite connotations of skulls and mummiforms, subject matter that might be construed as dark, the paintings bear witness to light. “These interiors are studies in light,” says Cynthia Madden Leitner, founder and CEO of Denver’s Museum of Outdoor Arts and the executive producer of “Daniel Sprick: Pursuit of Truth and Beauty,” a documentary film that was made for Rocky Mountain PBS.

Living Room | Oil | 16 x 20 inches

“Daniel has always seen the luminosity of the sublime,” says Leitner, an early champion and collector of Sprick’s paintings. “During the pandemic, he rose above the fray to see the beauty of how light falls upon objects or along the rim of a room. COVID-19 gave us all the opportunity to see captured beauty because we had to slow down, but Daniel always looks for the truth of beauty.”

Sprick found his inspired verisimilitude in domestic glimpses already randomly displayed in his apartment. “Every one of those was already set up, and I stumbled across them,” Sprick says of the paintings’ subject matter. “At one point, I was looking for a coat hanger and saw my bike there in the hallway and just thought, ‘Oh, my goodness, there’s a perfect composition.’ And five minutes later, I started to paint.”

For Sprick, the unexpected vision offers the most artistic gratification. “It makes it a joy. This series was full of surprises for me, and painting needs to have surprises,” he says. “I never really know how things are going to turn out, how they’re going to start or end. I had no idea what I was going to paint that day. I like that. That’s what I prefer, because that’s how it stays interesting and not dull.”

Compotes | Oil | 12 x 16 inches

As studies of light and shadow, portions of Sprick’s new paintings approach incandescence. Overall, the work, like lanterns, illuminate the dark times of disease and death, destruction and division so prominent during the pandemic.

“The goal is transcendence beyond using reality as a starting point,” Sprick says. “Temperature differences are tantalizing to me, so I have exaggerated them because any story worth telling is worth exaggerating — not to the extent that it looks unnatural or calls attention. Or I exaggerate in terms not of temperature, but of value. It’s very rarely transporting on its own. I modify practically everything, translating it into 2-D. I stay within the limits of Realism, though sometimes it steps out of that. I’m not confined by accuracy, but by plausibility and harmony.”

Whether considered as individual paintings or as a series, Sprick’s new works present a peek into the artist’s private life and offer visual succor in the form of domestic beauty.

Interior | Oil | 8 x 20 inches

“I would hope for a healing aspect. That’s not a conscious, forthright goal, but just what beauty is supposed to do — at least help us with some sense of well-being,” Sprick says.

“But those are thoughts when I’m not painting,” he adds. “When I am painting, I’m just trying to mix the right color and put it in the right place. I can’t do much other than that.”

That, as Sprick’s exquisite new series demonstrates, is plenty.

No Comments