05 Nov The World Stage

When JoAnne Northrup, the curatorial director and curator of contemporary art for the Nevada Museum of Art, was inspired to put an exhibition together that would have popular appeal and the legs to draw a younger audience, she turned to renowned art collector and philanthropist Jordan Schnitzer. Like other curators from museums of all sizes around the country, she was familiar with his family foundation’s lending program, which was based on Schnitzer’s collection of nearly 19,000 pieces. With a focus on prints and multiples, it also includes paintings, sculptures, photography, and the works of a wide variety of celebrated post-World War II contemporary artists, such as Andy Warhol, Ellsworth Kelly, John Baldessari, Roy Lichtenstein, Frank Stella, Chuck Close, Robert Rauschenberg, Edward Ruscha, Jasper Johns, and countless others. And it incorporates works from some of the most important up-and-coming names in the art world.

Kehinde Wiley, Marechal Floriano Peixoto II, from The World Stage: Brazil Series | Oil on Canvas | 107 x 83 inches | 2009 Collection of the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation. ©Kehinde Wiley. Courtesy of Roberts Projects

The Nevada Museum of Art had borrowed prints from Schnitzer’s collection in the past, for a 2007 Andy Warhol exhibition that was one of the most successful in appealing to crowds of all ages, along with a 2018 show on Enrique Chagoya. “Jordan has been incredibly generous and a supporter of the arts and of championing lesser-known artists,” Northrup says. “He collects certain artists in incredible depth, into the hundreds … and he’s always collected works by diverse artists.”

Diversity was exactly what Northrup was aiming for in a new exhibition. She reached out to the foundation, traveled to their headquarters in Schnitzer’s hometown of Portland, Oregon, and pored over the more than 150 binders that track each piece. “This was an opportunity for me to play,” she says. “Jordan has this spectacular collection, and he allows me to have free reign to select anything I want. I was like a kid in a candy store.”

Andy Warhol, Reigning Queens: Queen Ntombi Twala of Swaziland | Unique Screenprint on Lenox Museum Board | 39.5 x 31.5 inches | 1985 Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer

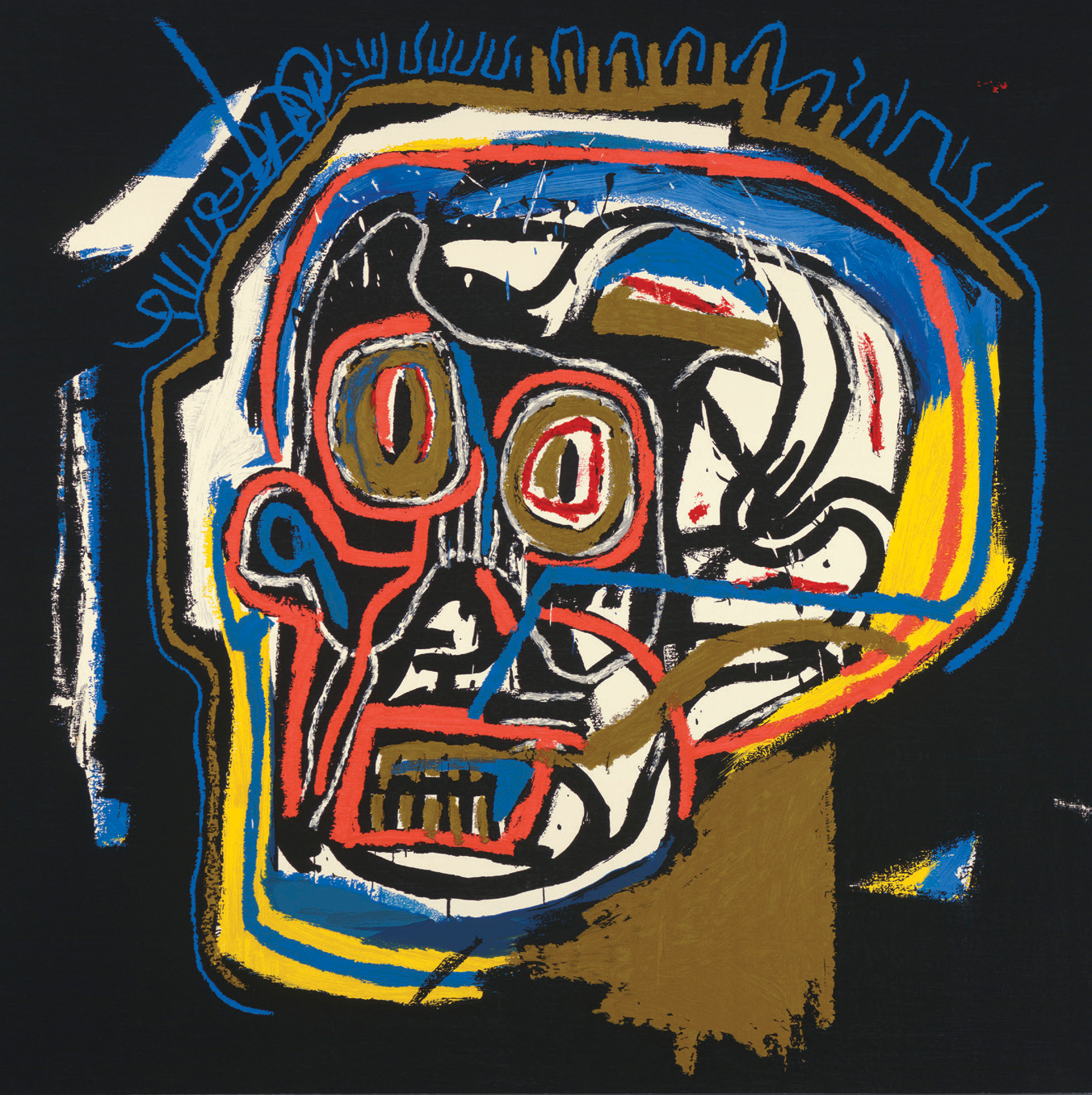

The end result is The World Stage, which features 90 contemporary artworks by 35 American artists — both well-known ones and up-and-coming global influencers — comprising a variety of media, from painting and installations to mixed media, with a special focus on prints, all of which were borrowed from the Schnitzer Collection. The exhibition runs at the Nevada Museum of Art through February 7, and then moves to the Boise Art Museum from March 6 through July 11, 2021. The title is borrowed from a series of paintings by Kehinde Wiley, an artist best known for his portrait of former President Barack Obama that hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C. To Northrup, this seemed like the perfect metaphor to represent the pool of works.

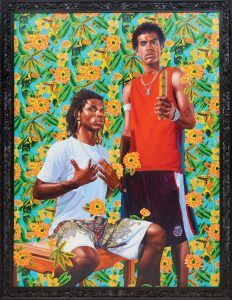

Mildred Howard,I’ve Been a Witness to this Game I Color Monoprint/Digital on Found Paper with Collage | 20.625 x 15.125 inches | 2016 Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer. ©Mildred Howard

“I was thinking about this 1951 Time magazine article called ‘The Irascibles,’” she says. “It focused on the best Modern painters in the nation under the age of 36, featuring [Jackson] Pollock, [Mark] Rothko, [Willem] de Kooning, and others. There’s an image of some posing together, and the thing that’s striking to me is that there was only one female artist in the group, Hedda Sterne. And in her oral history, she said she was made to feel that she didn’t belong there. I thought, ‘That’s OK because that was the world stage then, but the world stage has changed.’ Now the American artists on the world stage are not only white men, but also women and artists of color.”

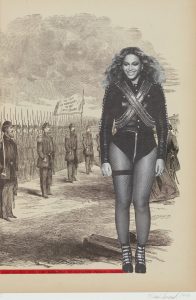

Andy Warhol, Reigning Queens (Royal Edition): Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom | Screenprint with Diamond Dust | 39.5 x 31.5 inches | 1985 Collection of the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation

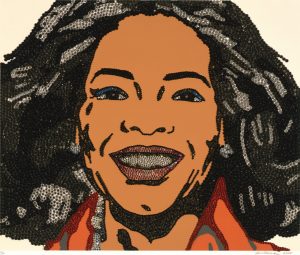

In a country that’s become divided by a number of pressing cultural issues, ranging from racism to equal pay for women, the timing couldn’t be better for an art exhibition that addresses these themes along with other social phenomena. For example, The Reigning Queens series combines a Warhol screenprint of Queen Elizabeth, a print of Beyoncé, who’s known as “Queen Bey,” by Mildred Howard, and the rhinestone-studded face of Oprah Winfrey, the queen of media, by Mickalene Thomas. “I was playing with definitions of what it means to be queen,” Northrup says. “Organizing an exhibition is like organizing a party; you want to mix it up, and that makes it the most fun. Some are valued superstars, and others are important artists but don’t yet have the reputation.”

Mickalene Thomas, When Ends Meet | Screenprint with Hand-Applied Rhinestones | 31.875 x 28 inches | 2007 Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer. ©2020 Mickalene Thomas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In that sense, this exhibition is very much a reflection of Schnitzer’s passion for championing new artists, honoring those that are household names, and including the works of diverse artists. “The art world is a strange place,” Northrup says. “It’s very challenging for women and artists of color to get in. If you show lesser-known and diverse artists alongside the cannon, it gives them more opportunity for visibility, and it expands peoples’ contemporary art vocabularies.” That, too, is exactly why Schnitzer decided to start a lending program in the first place.

Schnitzer’s passion for the arts was ignited as a child when his mother, Arlene Schnitzer, opened the Fountain Gallery in Portland, Oregon (now the Russo Lee Gallery). As the first contemporary art gallery in the city, its focus was on artists from the Pacific Northwest. And it’s where Schnitzer bought his first painting when he was 14, a small piece by Louis Bunce that he credits as the start of his infamous collection.

“My first love is the art of our region; I think we have some of the best artists anywhere,” he says. “I decided to continue buying art of our region, but thought it would be fun to buy prints and multiples. I’d always liked works on paper by major post-World War II contemporary artists, and I established one of the best collections [of prints], with works by Frank Stella, David Hockney, Jim Dine, Ellsworth Kelly, [Robert] Rauschenberg, and eventually hundreds of others.”

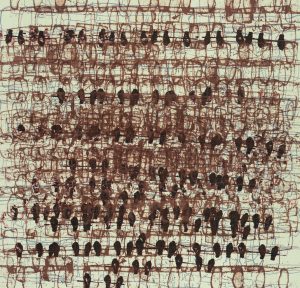

Mark Bradford, Untitled | Lithograph | 32.5 x 32.75 inches | 2003 Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer. ©Mark Bradford. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

In 1995, he lent some prints to the art museum at the University of Oregon, where he was on the board (now called the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art). He was immediately hooked. “Walking into that gallery with works from my collection was so very special,” he recalls. “I felt like I was walking into a room of friends, even though I didn’t know any of the artists personally at that time. I decided then to put some mission to my madness, and to develop an exhibition program to take these great artists’ work to people in various communities, including regional museums and less-served ones.” The program has since lent works to more than 140 exhibitions at 90 museums, averaging 15 to 20 per year. It has a staff of 9 people working full-time, and along with managing loans, they fund educational programs to coincide with exhibitions they’re involved in and have published 12 books.

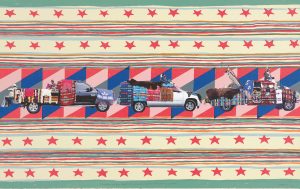

Wendy Red Star, iilaalée = car (goes by itself) + ii = by means of which + dáanniili = we parade | Lithograph with Archival Pigment Ink Photographs | 24 x 38 inches | 2016 Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer. ©Wendy Red Star

Schnitzer’s respect for the artists and artwork he collects runs deep, and it’s offered the busy real estate developer a valued place of respite. “Waking up without art around me would be like waking up without the sun — the art is that important to me,” Schnitzer says, explaining that it has the potential to deliver different messages to different people, whether it’s a quiet contemplation of beauty or work that makes one ponder the deeper meaning of life.

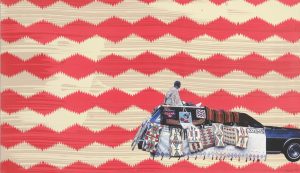

Wendy Red Star, Yakima or Yakama – Not For Me To Say | Lithograph with Archival Pigment Ink Photograph | 24 x 40 inches | 2015 Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer. ©Wendy Red Star

And Post-War contemporary artists especially appeal to Schnitzer. “Contemporary artists are always, in my opinion, chroniclers of our time,” he says. “They force us to deal with the issues in society. … And if they’re doing their job, they’re creating art that reflects these themes.”

Schnitzer believes that we are all artists in a way, but for it to be your life’s work, there’s a formula. “You need to, first, have a passion about something that you’re willing to make art about, and put your heart and soul out there where anyone can critique it. And, second, you’ve got to do it in a way that’s not been done before. I think some of the best artists of today are some of the diverse artists. Whether they’re Black, Native American, or Hispanic, when history looks back, they will see this as a time when these minority groups as artists came more into their own in all aspects of society.”

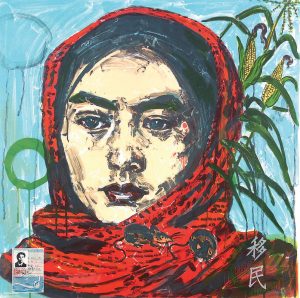

Hung Liu, Official Portraits: Immigrant | Lithograph with Collage | 30.25 x 30 inches Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer. ©Hung Lui. Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

This diversity is certainly represented through the works that Northrup pulled from Schnitzer’s collection to create The World Stage. And just like the first time he walked into a museum and saw his art on display, this show offers him the same sense of contentment. “I think it’s a brilliant exhibition,” he says. “As you move from wall to wall, room to room, you’re seeing some of the best and brightest of the artists today, showing us very different themes of society.”

For Northrup, the exhibition has been a way to stir up emotions in those of all ages, and to allow newer artists to shine. “I want viewers to leave with a sense of the incredible breadth of the art world right now. Artists can express whatever they want; there aren’t constraints. They have the latitude to express their own original points of view about gender, culture, the environment; it’s just really wide open. I also hope the public can learn about the amazing diversity of artists that are in Jordan’s collection.”

No Comments