11 Jan Collector’s Notebook: The Fine Art of Framing

A waggish art dealer once remarked, “A good painting needs a good frame, but a bad painting really needs a good frame.” Serious art collectors and critics agree that worthy artworks deserve worthy frames. It’s a simple but fundamental truth that a frame can make or break how the piece hangs on the wall.

Chris Kirkegaard, a respected and sought-after frame maker, describes the relationship between a painting and its frame in reverential terms: “A frame is a kind of interface between the artwork and the setting that surrounds it,” he says, adding that the frame has to resonate with the painting and should engage the viewer, without being a distraction.”

Nevertheless, Kirkegaard is quick to acknowledge that not every painting requires a frame. “A canvas with tremendous detail right out to the edges might hang best without a frame at all,” he says.

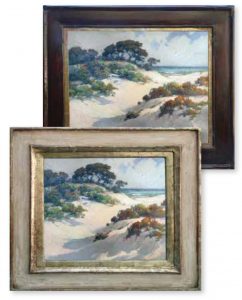

Jennifer Moses, Moonrise Santa Rosa Island | From top: Hand Carved and Water Gilt Frame, “Pie-Crust” Style | Hand Carved and Water Gilt Frame, 22k Moon Gold | Frames by Chris Kirkegaard

Complementing the painting isn’t the only thing one must think of, but also what the frame itself might contribute to the room where it will hang. For example, a frame chosen by the artist or gallerist might not fit in the collector’s home. One that brilliantly sets off a painting hanging among a sea of other images might not work as well in its new setting. Or perhaps the frame is a bit too loud to meld with the collector’s other works.

To reduce all the things a conscientious collector might consider down to a simple formula is impossible, but a good rule of thumb is that the architecture of the frame should enhance rather than detract from the composition of the painting. According to Kirkegaard, a “good frame design starts with considering the painting itself.” The frame, he says, “should echo the gestures within the painting.”

Martha Johnson, a framer at Queen City Framing in Helena, Montana, agrees. She explains that a Baroque frame would not be the best complement to a 20th-century Modernist work, for example.

A good frame has to correspond to the style and period of the artwork, and it should also blend in with the rest of the room where it will hang. That’s why, Kirkegaard points out, even if a collector consults a professional framer, “It’s important for the collector to take some authorship in choosing the frame.”

Percy Gray, Carmel Sand Dunes | From top: Hand Carved and Water Gilt Frame, Mahogany with 18k Gold Hand Carved and Water Gilt Frame, Antique Gesso Panel Frames by Chris Kirkegaard

A good frame should also include proper preservation. This often means choosing the right sort of glazing, or protective glass or acrylic, for high-end artworks like prints or photographs. Most collectors do not protect framed paintings behind glazing, Johnson says, but she notes that they see it “more and more, as clients nowadays are more aware of the damage that can occur without proper conservation.” It’s a practice generally relegated for especially old paintings.

From a preservation perspective, best practices include choosing framing and mounting materials that will not harm the artwork over time. “That means a good cotton base on the back of any paper, and using materials that will not bleed acid into the artwork, either from the wood in the frame or other materials,” Johnson explains. For prints, it’s important to avoid adhesives in the mounting process, although some special methylcellulose adhesives are acceptable for archival purposes when necessary.

The aesthetic principles that guide collectors in choosing artwork also work well for determining the frame. Let an eye for compositional balance and a judicious sense of color be your guide, and take time to ensure that the materials will allow the artwork to be appreciated by future generations.

An Eye for Fine Art Frames

Consider these words of wisdom when framing your next favorite..

As a general rule, the frame and artwork should match in style and era. An old masterwork or a historical painting is better suited to an ornate, hand-carved, or water-gilded frame than a Modernist work may be. If you want to go the distance, work with a skilled framer who can replicate period-appropriate frames.

Not all paintings or prints require a frame. A print might look best clipped behind archival glazing (glass or acrylic), depending on the background. And many modern paintings are not meant to be framed.

A badly-framed quality artwork is only marginally better than a mediocre artwork displayed in an expensive frame. Let the principles of aesthetics guide you: integration of form and function, balance, and what feels most visually pleasing.

Mounting prints should never involve adhesives unless they are archival-quality. Avoid dry-mounting an original print or photograph. This can decrease the artwork’s value.

For works on paper or photographs, never allow the glass to touch your artwork. Use spacers or a mat, which protect the work from condensation that can cause discoloration, mildew, and buckling.

A rule of thumb for choosing a mat: never use one that’s lighter, brighter, or darker than the lightest, brightest, or darkest portion of your artwork. And avoid using a color that doesn’t appear in the artwork, even if it matches the drapes.

Use UV-protection glass, which includes a special coating and blocks about 97 percent of UV rays. Avoid hanging artwork in direct sunlight, by a heat source, or near an area of high humidity. Museum glass blocks UV rays and also includes an anti-reflective coating to view artwork clearly.

No Comments