11 Jan Finding A Niche

One day a few years ago, Thomas Blackshear II got an email out of the blue from a friend — painter Morgan Weistling — whom he hadn’t seen for quite a while. Weistling didn’t know it at the time, but Blackshear was going through a difficult transitional period following a divorce and changes in his longtime career as an award-winning illustrator and the creator of a popular line of African American collectible figurines. He was ready for something new.

Weistling, for his part, wanted to see Blackshear’s considerable talent turned toward fine art and was offering to open doors for him. He told the illustrator that things were changing in the Western art market, and he believed his friend could find a niche there.

“What do you want me to do?” Blackshear asked, when the two spoke by phone.

Taking Flight | Oil | 63 x 29 inches

“Paint,” Weistling replied, “I’ll keep in touch.” He added that he would like Blackshear to be his guest at the Autry Museum’s Masters of the American West show the following year in Los Angeles.

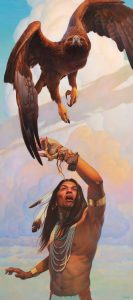

Back in his studio, Blackshear began exploring Western imagery in a style that brought together artistic influences that he had loved for years, in particular the graceful lines, stylized elements, and nature-inspired symbolism of Art Deco and Art Nouveau. What he developed was a distinctive contemporary approach he calls “Western Nouveau.”

He took along a portfolio of his new work when he accompanied Weistling to the Autry show. Among those he showed it to was Maryvonne Leshe, managing partner of Trailside Galleries in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, and Scottsdale, Arizona. “Why have I not heard of you before?” she asked, inviting him to join the gallery. Of Blackshear’s art today, Leshe says, “After more than 40 years in the business, it’s the most exciting work I’ve seen in a while. It’s unique, creative, and well-composed — he’s a terrific artist.”

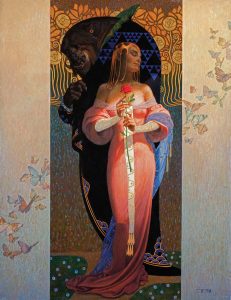

Within this contemporary-leaning framework, Blackshear matches his subject with one of three modes of expression: representational, a more stylized approach, and what he calls decorative, which incorporates dramatic patterning and often gold leaf. He also returns at times to creative ideas that have been incubating for years. Like Airman’s Inspiration.

Beauty and the Beast | Oil on Board with Gold Leaf | 34.5 x 26 inches

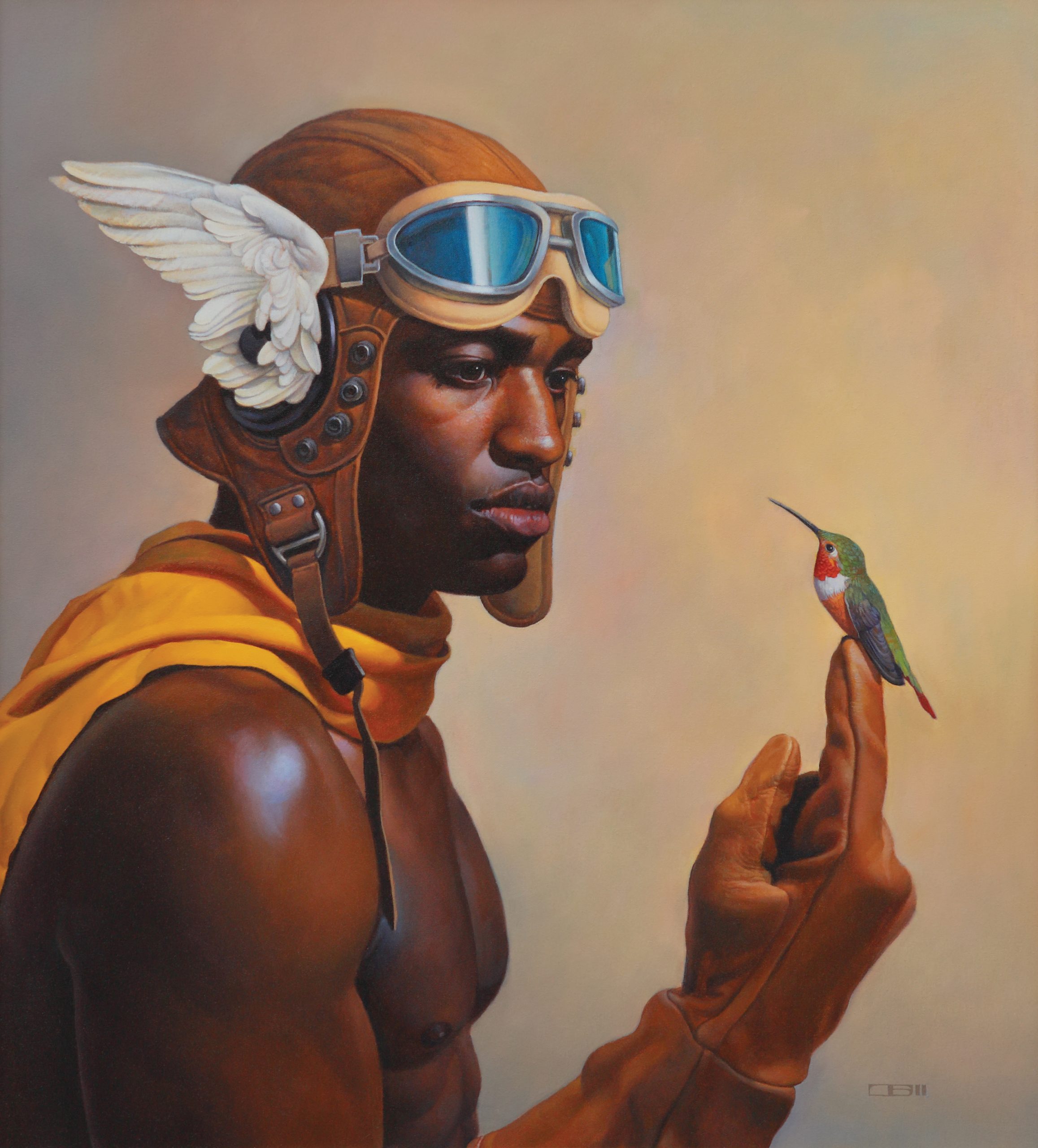

“Twelve or 15 years ago, I drew the idea of a pilot, a Black guy in a pilot’s cap with wings on it, like the god Mercury, and a hummingbird on the tip of his finger,” the artist says, speaking from his home in Colorado Springs, Colorado. The image was inspired by the history of the Tuskegee Airmen, the first African American military aviators in the U.S. Army Air Corps, who flew more than 15,000 sorties in Europe and North Africa during World War II. Because the unit’s fighter plane tails were painted red, the hummingbird in the painting has a red tail.Another image Blackshear had in the back of his mind emerged recently as Dragonfly, which portrays a woman in a museum standing in front of a mosaic of iridescent dragonfly wings. She holds a sword with a handle shaped like a dragonfly’s head. The blade stands in for the insect’s slim body. Inspired by the dragonfly and women as frequent subjects in Art Nouveau, Blackshear long imagined combining the two but didn’t want the woman to actually be the dragonfly. The piece is a tribute to the artists who have deeply inspired him throughout his career, including Gustav Klimt and Alphonse Mucha, known as the father of Art Nouveau.

For his part, Blackshear was honored last year with the highest tribute possible within the field of illustration. In October 2020, he was welcomed into the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame, joining the ranks of such esteemed artists as Norman Rockwell, N.C. Wyeth, Maxfield Parrish, and Winslow Homer. A couple of weeks after the ceremony — held virtually from New York City because of coronavirus restrictions — he remained deeply moved by the magnitude of the honor. “I’m still trying to figure out: Am I dreaming?” he says, smiling.

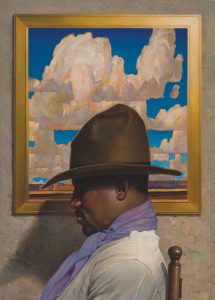

Dixon Dream | Oil | 30 x 22 inches

This year, Blackshear’s paintings will be part of the Autry Museum’s 2021 Masters Art Exhibition and Sale, opening February 27 in Los Angeles. He will also be a guest artist at the Prix de West Invitational Art Exhibition and Sale at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, June 25 and 26.

As an artistic child growing up in Atlanta, Georgia, Blackshear could not have imagined where his dreams would take him, but he had a strong intuitive sense that it would be someplace good. His parents knew early on that he had a gift: at 4 years old, he drew a cow that actually looked like a cow. When other kids were busy playing sports, he spent much of his time alone doing what he most enjoyed: drawing, especially fantasy and Disney characters. While his friends were assembling plastic monsters from model kits, young Blackshear was using Play-Doh to design and sculpt his own. Later a high school art teacher encouraged his creative exploration of ceramics while the other students made simple pots.

On a scholarship, Blackshear attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago for a year but found himself frustrated with the lack of foundational art instruction that was offered. He transferred to a university just down the street, the American Academy of Art College, from which he graduated with an illustration degree in 1977. Although he loved fine art, he “wanted to be an artist that wasn’t starving,” he says.

Recruited by Hallmark along with one other graduate, he moved to Kansas City — where his real-life art education began under the mentorship and as an apprentice to the great American illustrator and painter Mark English [1933–2019], who served as Hallmark’s in-house illustration teacher.

Blackshear remembers the day he showed English his first painting for the class, an assignment he completed well before the deadline. English studied the painting, looked at his student, looked at the painting again, and turned back to Blackshear. “Very nice. Very nice,” he said admiringly. He passed the painting around the class and then asked to see it once more as if to confirm the level of accomplishment. Two weeks later, he asked Blackshear to be his apprentice, assisting him with commercial illustration jobs. “Working with him catapulted me to a whole new level of understanding — about design, about business, and how to have confidence in myself as an artist,” Blackshear says.

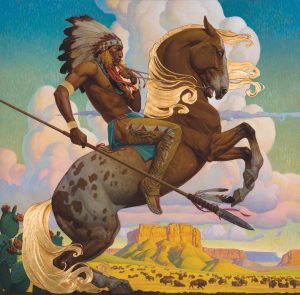

Buffalo Hunt | Oil on Board with Gold Leaf | 48 x 48 inches

A few years later, Blackshear was living in Los Angeles, hoping to break into special effects in the movie industry, when he received a call from English asking for assistance on a major job. He returned to Kansas City and lived with English and his family for three months while completing the project. Then, he accepted a job that led to a position as head illustrator for a prominent Kansas City design studio.

In 1982, Blackshear shifted to freelance work and moved to the San Francisco Bay area, where he established a presence in illustration for the film industry. He also found a niche designing collectibles, including George Lucas film plates and U.S. postage stamps. Over the years, he produced paintings for numerous stamps, including four in the Black Heritage series, which was part of a touring exhibition that opened at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History.

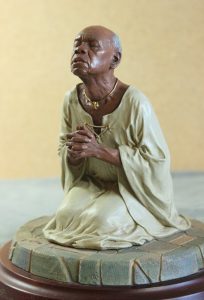

Reaching back to his early interest in ceramics and sculpting, Blackshear created Ebony Visions in 1995, which soon became the country’s top-selling line of collectible porcelain-resin black figurines. He calls the style Afro-Nouveau and describes the figurines as “Black people in loving and relational situations” — for example, a young father tenderly holding his infant son. The series became so popular that he enlisted one of his former art students to sculpt, while Blackshear designed new pieces. He was also creating Christian art, celebrating his faith with work that took him to the Vatican as part of a 2006 exhibition where he unveiled his painting of Pope John Paul II.

The Prayer, Ebony Visions Series | Porcelain Resin | 6 x 4.5 inches Designed by Thomas Blackshear II, Sculpted by Thomas Blackshear II and Mark Newman

While illustration work and royalties from collectibles eventually allowed Blackshear to turn his attention to painting for himself, he wasn’t known in the fine art world. Having settled in Colorado Springs, he was looking around at Western art and how it could fit with his talent and interests when Weistling contacted him.

Krista Steed-Reyes, director of Broadmoor Galleries in Colorado Springs, is another gallerist who quickly recognized and appreciated the artist’s approach to Western imagery and other subjects. “Thomas is creating work and bringing to life ideas that no one else is doing right now, and it’s refreshing to see something unique,” she says. “His use of color and texture captures people’s attention and keeps drawing them in. I like that he doesn’t only paint one thing. It’s exciting to think, ‘what’s next?’”

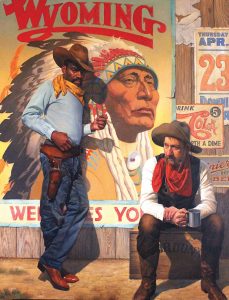

In fact, Blackshear intentionally maintains a broad scope of subjects and styles. He creates pensive portraits of Native figures, and both African American and white cowboys in timeless settings or juxtaposed with elements borrowed from Art Nouveau. Other paintings reflect his continued interest in fantasy, symbolic imagery, and Christian themes. Unwilling to be pigeonholed as a Black artist who paints Black cowboys, he says, “I’m an artist who happens to be Black.” He’s also an artist who credits his faith and perseverance — along with talent — in propelling his career.

Cowboys and Indian | Oil | 50 x 39 inches

But there’s one other factor, Blackshear says, and it’s an important lifelong lesson he learned as a teen. In high school, there was a fellow student who was better at art than anyone he had met before — or since. Meeting this boy “did a number on me,” he remembers, “because I had always been the best. I realized I will never be the best, but I can be the best that I can be. It was such a blessing to see that the only one I have to compete with is myself. I learned there’s no need to compare. Just keep finding the love for what you do, and just keep doing it.”

No Comments