15 Mar Unearthing

When Wendy Red Star talks about her work, she describes the way things click. Sometimes when she’s driving. Almost always when she’s home. For Red Star, the art is a result of the process: the right medium arises from the concept, which emerges after she surrounds herself with — and is most often overwhelmed by — objects, questions, and connections to her own family and the Apsáalooke tribe to which she belongs. She stays open, she says. She absorbs as much as she can. She turns it all around and around in her mind. And then it clicks.

“Sometimes it’s right there,” she says. “And sometimes it takes years for things to come together.”

Red Star’s newest exhibition — a three-dimensional photographic installation inspired by the 1898 Indian Congress in Omaha, Nebraska — opened in the Joslyn Art Museum’s Riley CAP Gallery in January and is on display through April 25. The installation has been in the works for more than four years, since her 2016 residency at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, also in Omaha.

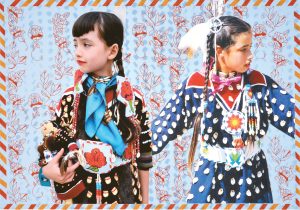

Apsáalooke Roses, Four-Color Lithograph with Archival Ink-Jet Pigment Print Chine-Colle, 18 x 26 inches, 2015, Edition of 12, Collaborative Master Printer, Frank Janzen TMP, Photo Courtesy of Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts

Red Star pursued ideas in her usual way: by looking for Crow (Apsáalooke) objects in the museum’s Native American art collection to see if there was a personal connection for her, something she describes as “biological.” What she discovered is that a Crow delegation attended the 1898 Indian Congress in Omaha, and were among the 500 Native Americans from dozens of tribal nations. She kept digging — studying the photographic portraits of the delegations taken by white photographer Frank Rinehart, looking for more connections.

She found them.

Catalogue Number 1950.76, Pigment Print on Archival Paper, 2019, Edition 1 of 10 plus 2 Artist’s Proofs

Following the Indian Congress — which Red Star explains was really a marketing ploy for the Trans-Mississippi Exposition, a way to capitalize on the fascination with Native people to draw more visitors — Rinehart traveled west to the Crow Reservation in Montana. There, he photographed tribal members near Pryor Gap, the place where Red Star grew up and where her father still lives. While she appreciated the beauty of Rinehart’s Indian Congress portraits — and the fact that he wrote down the sitters’ names and identified the communities where they were from, something Red Star describes as very progressive for the times — she was fascinated to see how different the images were when her people were on their home ground. She wanted to include images from both places in her installation.

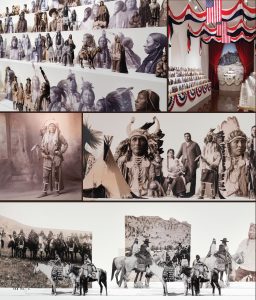

Catalogue Number 1935.33.a,b, Pigment Print on Archival Paper, 2019, Edition 1 of 10 plus 2 Artist’s Proofs, Images Courtesy of the Artist and Sargent’s Daughters

Her meticulous excavation also revealed a connection to Alexander Upshaw, who was among the first Crow children to be sent to the Carlisle Indian School — which operated under the motto, “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.” After working as an interpreter for the Crow Delegation in Nebraska, where he had been hired as a teacher at the Genoa Indian School, Upshaw went on to interpret for and collaborate with famed photographer Edward Curtis while he took photos on the Crow Reservation in the early 1900s. “All of the work I do connects because they are various pieces of the historical timeline I am unearthing,” Red Star says.

When visitors enter the long, narrow Riley CAP Gallery, the room will be set up with a sculptural arrangement of tables and shelves, reflective of the booths at the Exposition that Joslyn curator Annika Johnson describes as “almost humorous in their triumphant display of American consumerism … They’re quaint and also horrifying, if you know what was happening to Native people and the unbelievable damage that western agricultural practices have caused to the environment.” On her re-created display booths, Red Star will arrange more than 500 cut-outs of every portrait Rinehart took at the Congress, each with the subject’s name included.

The Indian Congress | Mixed Media Installation at the Joslyn Art Museum 2021 | Photos: Colin Conces

“Wendy’s installation honors the sitters,” Johnson says, “and conceptually reunites the Congress, which was one of the largest intertribal gatherings until water protectors gathered at Standing Rock in 2016. It brings up the complexities of their personal experiences through a dramatic immersive environment.” On display as well will be the images Rinehart took on the Crow Reservation the same year, and Red Star’s own photographic mural of modern-day Pryor Gap.

What Red Star wants is for viewers to experience the feeling of being amongst the Natives who attended the 1898 Indian Congress. “I want them to know it was this great event,” she says, describing the “overwhelming sense of the Indigenous” amongst the roughly 50 tribes in attendance. “And just to be in their presence,” she says.

Alaxchiiaahush/Many War Achievements/Plenty Coups 1880 Crow Peace Delegation Series | Pigment Print on Archival Photo | 24 x 16.45 | 2014 Courtesy of the Artist and Sargent’s Daughters

Johnson and Red Star agree that the Exposition and Indian Congress are not well-known events, even among Omaha residents. But they matter. And that’s how Red Star’s work clicks for viewers.

“Wendy restores personhood to the Indigenous sitters that white men photographed,” Johnson says. “Without Wendy’s intervention, I think the portraits would seem remote to today’s viewership, especially non-Native viewers. Her work is addressed to Indigenous and non-Indigenous viewers alike. Her work as a feminist is to intervene in these histories, and to conduct meaningful empathic research that rejects the hierarchy of so-called scholarly expertise that is inherently patriarchal.”

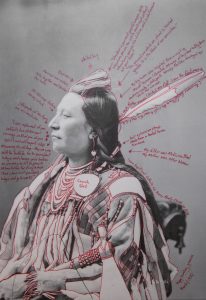

Peelatchiwaaxpáash/Medicine Crow (Raven) 1880 Crow Peace Delegation Series | Pigment Print on Archival Photo | 24 x 16.45 | 2014 Courtesy of the Artist and Sargent’s Daughters

Her exhibition at the Joslyn isn’t the first time Red Star has used meaningful and empathic research to delve into Crow delegations and her own personal and biological links to the past. In 2014, her series of annotated photographs of the 1880 Crow Peace Delegation were exhibited and purchased by Oregon’s Portland Art Museum, the city where Red Star currently lives with her teenage daughter, who is a frequent collaborator. Over the portraits of five Crow chiefs, including Medicine Crow — taken by white photographer Charles Milton Bell on behalf of the U.S. government — Red Star used a red marker to give viewers wonderful and arcane details about the clothing they wore, what individual pieces and elements represented; important historical facts; and even sly commentary and stories about each sitter. “I wanted to show the viewer that these are real people. These aren’t just a symbol of the Native spirit … I wanted to show that this is much more complicated than this aesthetically pleasing image,” she said at the time.

Dust | Lithograph (Color Trial Proof) | 2020 | Courtesy of the Artist

At the Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts on the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation in Oregon, where Red Star has been the artist in residence three times in just 10 years, her work gets even more personal. During her October 2020 residency, Red Star created three dynamic lithographic prints that incorporate images of her family, including her great-great-grandmother, Julia Bad Boy; her grandmother, Amy Bright Wings Red Star; her father, Wallace Red Star Jr.; herself; and her daughter, Beatrice Red Star Fletcher. Red Star cut out the images, as she did for her Joslyn exhibition, then set them against the vibrant backdrop of star quilt patterns.

Karl Davis, executive director of the Crow’s Shadow Institute, believes her work resonates so broadly with viewers because of both the ideas and the aesthetic in her images. “By incorporating her family, her ancestors, and the history of the Crow People, Wendy creates ‘real’ images that draw people in,” he says.

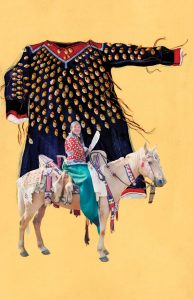

Four Generations: Iikua Biluxbakush “Self Reliant,” Báakoosh Kawiiléete “Kind To Everybody,” Baahinnaachísh “One Who Is Talented,” Apitebía “Sandhill Crane Woman” | Lithograph (Color Trial Proof) | 2020 | Courtesy of the Artist

Over the course of her third two-week residency, Red Star worked with master printer Judith Baumann and apprentice Maggie Middleton on the colorful prints that will be released by the institute sometime in the spring of 2021. Red Star’s work has sold out after each residency, and Davis doesn’t expect this year to be any different.

For Red Star, every project provides an extraordinary opportunity to learn. In addition to her large-scale museum exhibitions, Red Star has worked in a variety of media, including sculpture, video, fiber arts, photography, and performance. She’s also taken on roles as curator, editor, and adjunct professor, something that she says puts her in a position to support other artists. “Wendy is a very prominent voice in curating and scholarship, as well as her own art,” Davis says.

“I just like to be pushed out of my comfort zone,” says Red Star. “I love learning. I love asking questions. I’ll try anything once.”

When she talks about the role of art in her life, and particularly as a child growing up on the Crow Reservation, Red Star’s cadence slows a little. She was dyslexic, she says, and held back a grade in elementary school. “I never thought I was good at anything,” she says. But one great teacher changed everything by seeing and believing in her art. “Art has been a way for me to speak the loudest and the most confidently,” she says. And in this time in history, there are voices, long silenced, that need to be heard. “At the heart of it,” says Red Star, “art is a way of communicating.”

No Comments