05 May Portraying the Private Lives of Animals

When Laney paints wildlife, she studies her subject’s habitat, environment, weather conditions, and behavior. In other words, it’s not just a pretty picture. Her work entails hours of observation, detailed examination, and research into the species and landscapes she captures.

Lord and Master | Oil | 24 x 15 inches | 2019

“I’m really lucky that I live on the Wind River Indian Reservation, and my closest neighbor is a mile away,” says Laney. “It’s an advantage because the wildlife knows that.” She only needs to walk out her door to notice the moose clustering for safety, cottontails using a haystack for shelter, and chukars huddling under the sagebrush.

All of the artist’s ideas directly come from observing nature. “In the wildlife field, there are two kinds of artists: The first is where the ideas come from within, and those pieces come from a personal internal aesthetic; the second is where my artwork comes from — I look outside myself to get my ideas,” she explains.

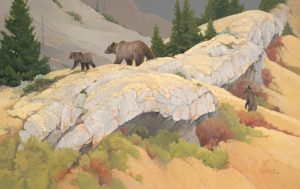

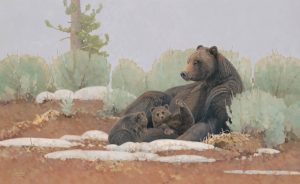

In her work, the habitat is just as significant as the animals. Although the main focus seems to be the wildlife, their environment comes through in more than a supporting role. Her observations of lichen and moss on wind-sharpened rocks, a snow-drifted outcropping, or the autumn-gilded aspens towering above high grasses all deepen our understanding of the portrait.

“I have my own style, an internal aesthetic imposed on top of what I see outdoors,” she says. “I have access to wildlife 24/7, and I tend to paint what I’m familiar with and keep to the Northern Rockies.” But she likes to keep her artist’s eye challenged. “If I paint a cottontail, I want to look for another species next time.”

Rabbitbrush | Oil | 13 x 16 inches | 2021

Laney, who prefers to be called by only her first name, moved to Wyoming from Denver while working with the Sierra Club as the Northern Plains representative. “It was a full-time job, and I didn’t do any artwork,” she says. Eventually, she burned out and went back to painting. “But I use my art as environmental education to wake people up to what nature is and what’s at stake; what people need to see and appreciate. Put your cell phone down and look with your eyes!”

This passion for nature drives her art. She hopes to stimulate viewers and inspire them to go outside, look a bit closer, and appreciate the wildlife and landscape that surrounds everyone. This is one of the reasons she was invited to participate in the National Museum of Wildlife Art’s exhibit Bonheur and Beyond, which runs through August 16 in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, and celebrates women in wildlife art, according to Tammi Hanawalt, an associate curator at the museum.

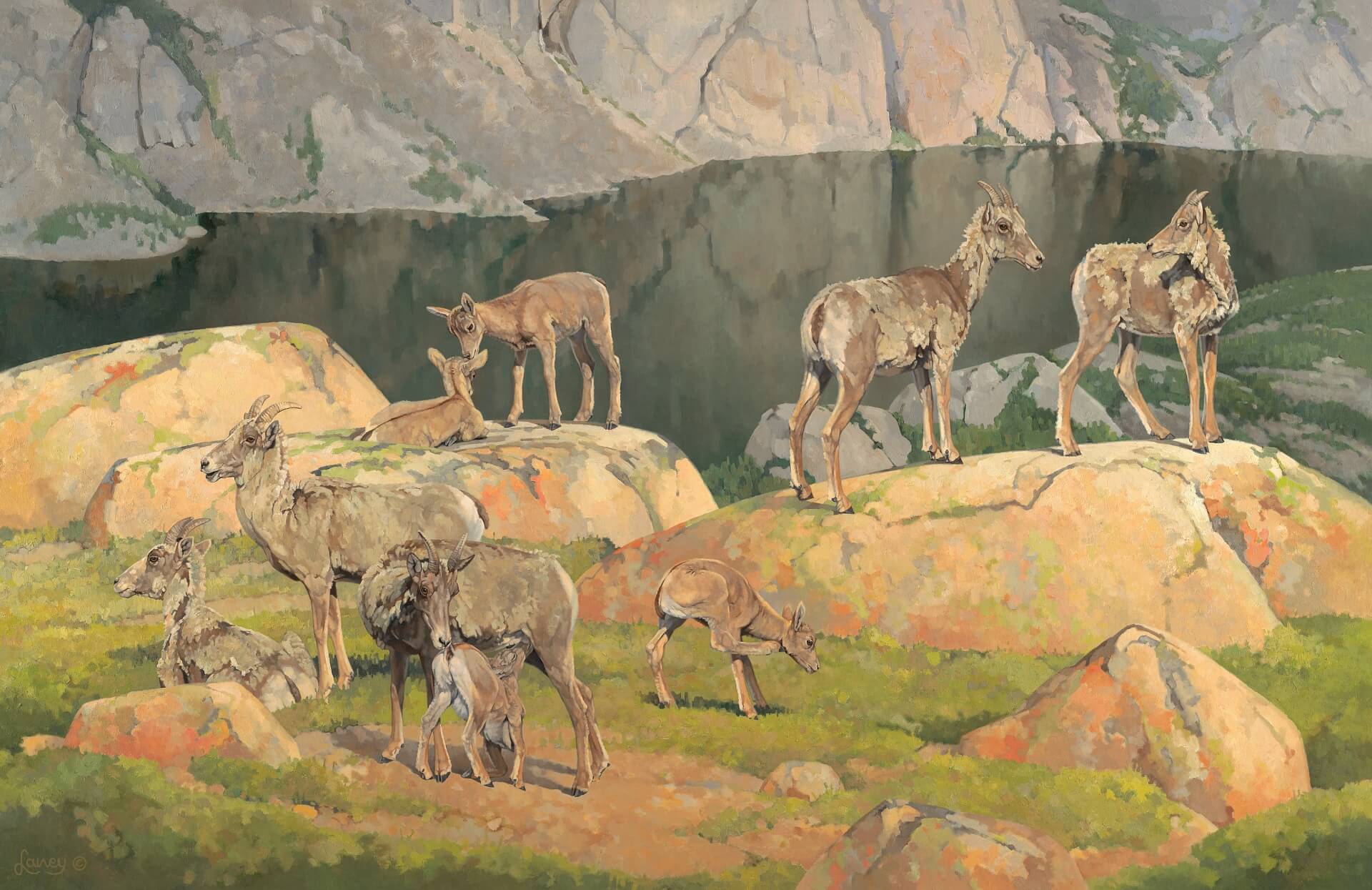

The Land Is My Land | Oil | 20 x 32 inches | 2020

“Laney’s art reflects where she lives, the animals and the habitats she sees daily,” Hanawalt says. “[She] gives her subject matter personality — and I look for that — because she knows her subject matter so well. She lives in the middle of a piece of wilderness. Right outside Dubois, you can see those mountain sheep and their young that she captures so well.”

The piece that will be featured in the show, Above Ross Lake, depicts bighorn sheep, specifically a ewe and her lambs. “Mother and [young] is a big theme for women artists. In this exhibit, we have 51 pieces, and none show violence,” Hanawalt says, adding that the importance of female influence in the animal kingdom is a common theme in the exhibit. “It’s the females that lead the migration, handling the regeneration of everything, and this is a perfect way to highlight that as well. Women have been overlooked in art, so it’s really wonderful to highlight them. Traditionally, in wildlife art, the theme is hunting with a masculine take, but there are plenty of women doing wildlife art.”

The National Museum of Wildlife Art opened 35 years ago with Bill and Joffa Kerr’s collection and included Laney’s artworks. “Bill and Joffa saw Laney’s work and recognized a very good artist. Aside from that, Laney has been a good friend to the museum,” Hanawalt says.

Morning Shadows | Oil | 12 x 20 inches | 2018

Currently, Laney has a painting of three bighorn ewes with two lambs on her easel. The first thing she did was search through her own photographs for reference material. “I make a rough sketch of each of the ewes and put them on separate pieces of paper so I can move them around in a small miniature layout,” she explains. “Then I decide on my habitat.”

The background she is working on is a luscious juniper tree in Torrey Creek, Wyoming. After she decides where to place the sheep in her composition, she’ll create a value sketch with marker pens. Then, she enlarges the sketch and transfers it to her gesso board.

Mountain Blue | Oil | 17 x 28 inches | 2021

“I first go over the piece with a wash with turpentine and paint,” she says. “I then look at the sky, rocks, sheep in front, and then the foreground. I can get carried away with negative space, punching a hole in a tree so the sky shows through. Then the painting evolves as it progresses. The juniper tree will be the main dark shape, and everything radiates out from that.”

Barbara Love and Steve Cutcliffe don’t formally consider themselves “art collectors,” but they do collect Laney’s work. In the last several years alone, they’ve bought four of her paintings. “Steve and I have always been fans of 19th-century landscape painting, and the wildlife painting of hers parallels that interest,” Love says. “She is an excellent painter of wildlife, but the settings are, to me, equally interesting and appealing. I grew up in Wyoming, and one of our paintings looks through aspen trees and captures the magic of the place. Her depiction of the landscape reminds me of home, even though we’re living in Pennsylvania.”

River Rocks | Oil | 14 x 24 inches | 2019

Cutcliffe is attracted to Laney’s work because he’s drawn to her large animals. “I tend to be a big animal person, especially her paintings of sheep, moose, and bobcats,” he says. “As an undergraduate in Maine, our mascot was a bobcat. One of our paintings shows a bobcat coming out from the forest onto a field of snow. It really appealed to me.”

They have a cabin outside Dubois, Wyoming, and visit with Laney every summer to see what she is working on. “She’s always got something interesting on the easel,” Love says.

Laney calls herself a naturalist artist rather than a wildlife artist because it’s not always the animals that drive her work. Depending on what moves her, she may concentrate on the land, the habitat, or the environment, although animals and settings alike usually make an appearance.

Wilderness Mom | Oil | 15 x 24 inches | 2021

“There are a great number of wildlife artists that don’t focus on habitat,” Laney says. “The reason I do this is that I’m highly influenced by Japanese and Chinese scroll art, and they never paint just the animal. There’s always a scene that goes with it. It’s a better idea of the real world.” She pauses and adds, “Man is little, and nature is big.”

No Comments