06 Sep Men Of Distinction

When people talk about art meccas, New York City, Paris, and L.A. come to mind. Colorado Springs, however, not so much, if at all, which is unfortunate because, at the turn of the 20th century, thanks to philanthropic visionaries Julie and Spencer Penrose, the town drew influential painters, printmakers, sculptors, and photographers to the Broadmoor Art Academy (1919 – 1936).

By 1937, the academy had morphed into the Colorado Springs Fine Art Center, which continued to bring luminaries such as John F. Carlson, Birger Sandzen, and Robert Motherwell to the state.

Dean Mitchell, Preacher | Acrylic | 14 x 25 inches

As a nod to the academy’s illustrious past and the Penrose family, John Marzolf, owner of the Broadmoor Galleries, and his curatorial staff have developed a series of lectures, workshops, and exhibitions showcasing some of the best representational artists today. Their line-up for November includes three icons of Contemporary Realism: Dean Mitchell, Ezra Tucker, and Thomas Blackshear.

All three artists will come together to exhibit new work, with an opening on November 10. And Tucker and Blackshear will conduct a workshop with four-and-a-half-days of painting instruction. True to the original vision of bringing important artistic voices to Colorado, these men bring the history of the Black experience in art.

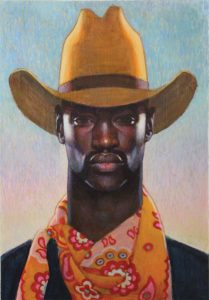

Thomas Blackshear, Neon Cowboy | Mixed Media | 9.5 x 6.5 inches

“I’m interested in having a deeper conversation about the West,” says Mitchell, who lives in Florida. “I don’t want my work to be this Black narrative thing. I want people to understand that this is a Black experience.”

Mitchell explains that during his first visit to a reservation, he felt a strong connection to his past and the extreme poverty and prejudice he faced growing up. “That experience of seeing the reservation crossed over from a Black experience into a human experience,” he says. “The Black experience can be felt on the reservation, and the Native American experience can be felt in the South.”

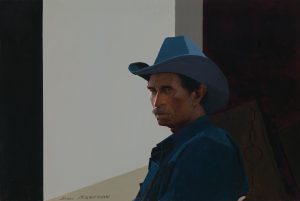

Dean Mitchell, One in Four | Acrylic | 20 x 30 inches

Tucker was born and raised in Memphis and Blackshear in Atlanta, but both have since made their homes in Colorado. The three artists first crossed paths nearly five decades ago, each man fresh out of art school, when they were hired as illustrators at Hallmark Cards in the late ’70s.

Tucker, who started at Hallmark a few years before Blackshear and Mitchell, recalls being told that he was hired because of Affirmative Action; he filled a quota. He realized from the start that he would have to work twice as hard — and he did — to prove himself repeatedly. He was never late, never missed a deadline, and turned in impeccable work only to be told to slow down, not work so fast; he was making the others look bad.

Blackshear, who was recruited to join Hallmark out of college, was selected to work with the company’s in-house illustration teacher, renowned illustrator Mark English, who gave the young artist the confidence to eventually forge his path in freelance illustration. He left Hallmark just before Mitchell came on, but Tucker introduced them to each other. “We were all single, in our early 20s, and new to the art world,” Tucker recalls. “We’d sit around and talk about what we wanted to do with our art. And we helped each other understand that we were not alone. We talked each other through that isolation we were feeling.”

Dean Mitchell, The Crosses We Bear | Acrylic | 22 x 30 inches

“The institutionalized racism you had to deal with was painful,” Tucker recalls. “I did make some advances, but every day there was another obstacle.”

Mitchell, who always knew he wanted to be a fine artist, not a commercial illustrator, was busy setting himself up to leave Hallmark early on by entering the fine art paintings he did after he got off work into national competitions. When he started winning tens of thousands in prize money, he drew the ire and jealousy of some of the older illustrators at Hallmark, who finally drove him out. Though Mitchell struggled and barely scraped by for years while trying to establish himself as a fine artist, leaving Hallmark was the best thing that could have happened to him, he says.

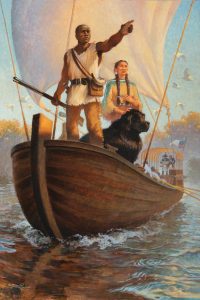

Ezra Tucker, The Devoted Servants | Acrylic | 30 x 20 inches

The support system these men formed proved invaluable as they navigated the corporate world and then left to follow their paths. They talked through ways around the racism that kept them from thriving. Blackshear and Tucker, for example, had illustration representatives who got them jobs, and Mitchell applied to shows but never sent in a photo of himself even when asked to do so, which kept race out of the equation.

It wasn’t always smooth sailing, but their friendship gave them encouragement. And while Tucker and Blackshear logged grueling hours creating illustrations under high pressure, Mitchell stayed the course, focusing on his fine art career, making works that were meaningful to him. Eventually, Tucker and Blackshear were able to cross over into fine art and, with guidance from Mitchell, learn the ropes of a new market, where they could create the work that they had dreamed of doing as young illustrators.

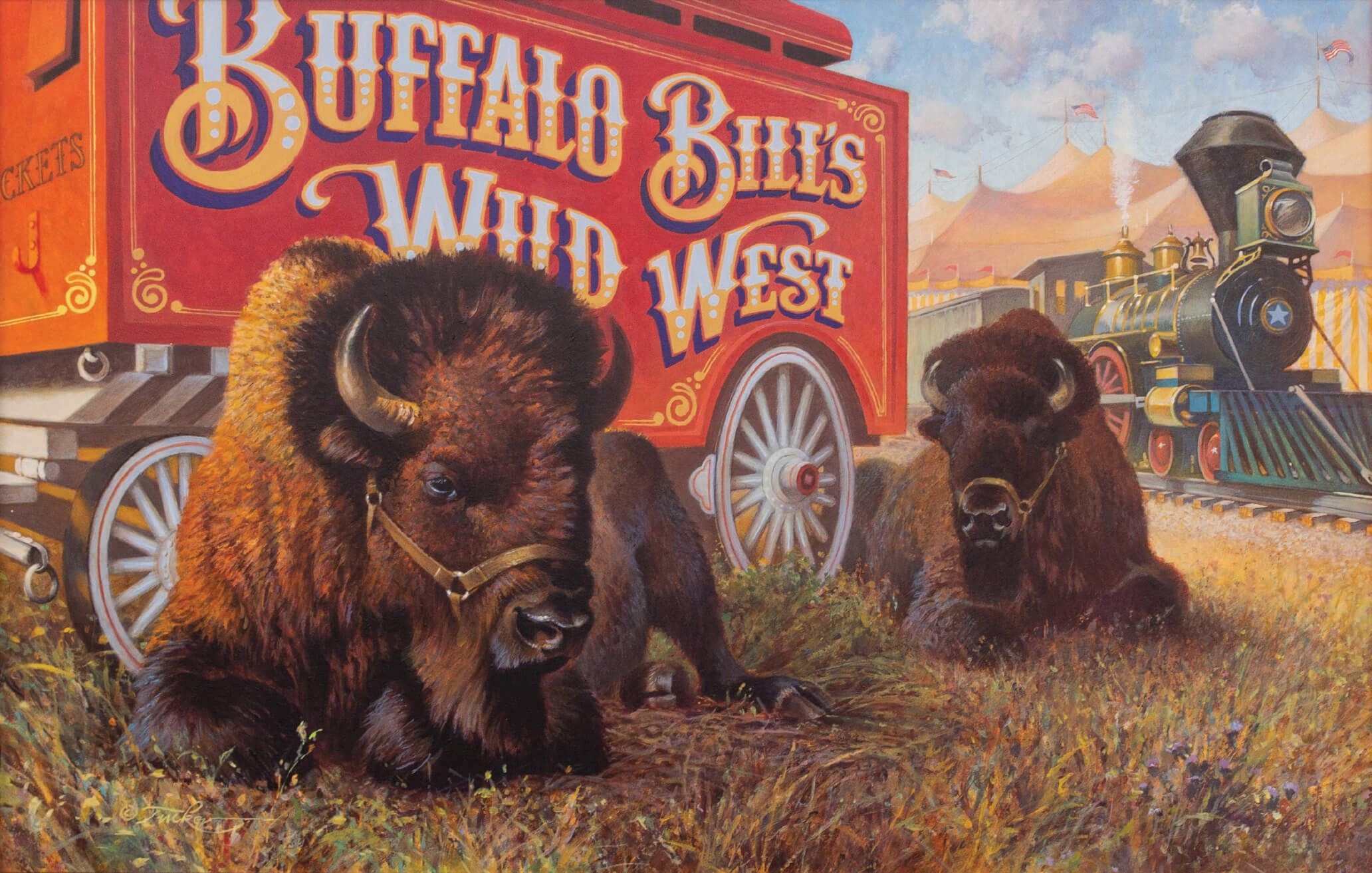

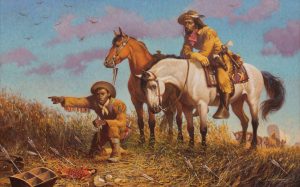

Ezra Tucker, They Went Yonder | Acrylic | 20 x 30 inches

When it comes to subject matter and how the Western U.S. plays a part, Mitchell has had more years honing his voice and sharpening his focus. He has also paved the way for other artists of color to join the conversation. These days, Mitchell recognizes that his audience is made up of younger collectors who are interested in modern visions of the West, not romanticism. This wasn’t the case when his work started appearing in major Western exhibitions, however. “I wanted to make money,” he says, “but being a part of Western shows has never been about money for me. I want to have a conversation about marginalized people. Collectors are not used to seeing Black people in art. But now there’s a movement in the world and an awareness — and record-breaking auction prices — for Black artists. Black celebrities have discretionary income, and they’re showing up at major art events. Bottom line: The world is changing and, I think, people see a market now.”

No Comments