07 Nov Perspective: Pictorial Pride

Last summer, turn-of-the-20th-century photographer Royal W. (Roland) Reed Jr. finally received recognition for his imagery of Indigenous Americans at a permanent exhibit in Steamboat Springs, Colorado. The Roland Reed Gallery has been a long time coming and honors an artist whose untimely death in 1934 left him near penniless, buried in an unmarked grave in Colorado.

Reed, an unsung contemporary of Edward S. Curtis, was a self-funded, self-directed photographer and fastidious artist who devoted years to photographing traditions and customs of Native American tribes, including the Anishinaabe (Chippewa/Ojibwe) in Minnesota; the Pikuni Blackfeet (Piegan), Northern Tsitsistas/Suhtai (Cheyenne), and Kainai Blackfoot (Kainah/Blood) in northern Montana and southern Canada; and the Diné (Navajo) and Hopi in the U.S. Southwest.

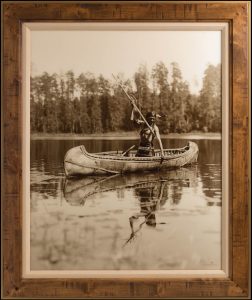

The Fisherman Ojibwe | Limited Edition Photograph, Metallic Print with Acrylic Laminate | 41 x 47 inches framed | c. 1908

Unlike Curtis, who captured more than 40,000 images, Reed’s collection was limited to several hundred glass plate negatives for two main reasons: the cost and time it took to gain the trust of his subjects to stage and capture their most authentic selves. Reed shunned commercial gain from his work, turning down large dollar amounts for fear of exploiting the people he held in high regard.

Born in 1864 in the Fox River Valley of Wisconsin, Reed was raised in a log cabin close to a trail linking Lake Poygan to Fond du Lac. The trail was often used by members of the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin, whom Reed immediately admired. He wrote in his journal, “I never forgot those tall, slim boys with their bow and arrows. As I watched them file along the forest trail, I long[ed] to join them, and as I grew into manhood and left my native state, the call of those old friends of the forest and lakes never left me. I could ask for no greater honor at this late date than to meet and shake the hands of those fine Indian boys who passed my forest home so many years ago.”

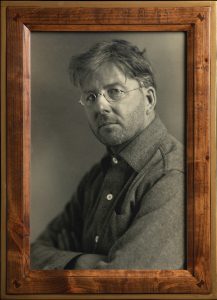

A self-portait of Roland R. Reed [1864 – 1934]

But drawing proved laborious, and Reed became enamored with the idea of photography. A fortuitous meeting in 1893 with Daniel Dutro, a portrait photographer in Havre, Montana, would change the course of Reed’s life and result in an apprenticeship and his career as a portrait photographer with several studios.

In 1907, he embarked on what became his life’s work. “I locked up my studio, ordered plenty of photographic material and other supplies, and started on my long-deferred campaign in portraying the North American Indian,” Reed wrote in the early 1930s.

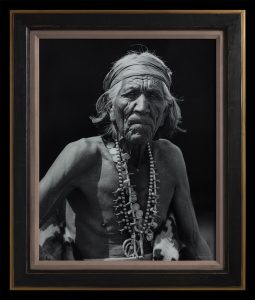

The Eagle | Limited Edition Photograph, Metallic Print with Acrylic Laminate | 48.5 x 58 inches framed | c. 1912

Reed was devoted to Pictorialism, a term derived from an artistic movement introduced in the 1860s in Europe. It inspired self-expression in imagery through tonality and composition rather than the traditional scientific approach to photography of the era.

“Did he use artistic license?” asks Brian Lebel, an antique appraiser and founder of Old West Events, a bi-annual art auction and show held every January in Mesa, Arizona, and every June in Santa Fe, New Mexico. “Absolutely. He wanted to make people look good by reimagining situations using authentic artifacts from the various tribes to create emotive imagery. We need to remember he was an artist and not a historian.”

Curtis, Reed, and their Pictorialist contemporaries were later criticized for misrepresenting Indigenous people and fostering stereotypes. Among those to question their work is the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum, which held an exhibit in 2019 titled (Mis)Representation. “When contemporary viewers are not challenged in the inherent romanticism of these images, damaging stereotypes persist,” says Leah Davis-Witherow, curator of history at the museum. “Reed captured various tribes as they were in the past — not as he found them in the present.”

Proud Heritage | Limited Edition Photograph, Silver Gelatin Print with Acrylic | 42 x 28 inches framed | c. 1911

In 2012, the book Alone with the Past by Ernest R. Lawrence was published and declared a catalogue raisonné for Reed by Sandra Starr, who at the time of publication was a senior researcher for the Department of History and Culture at the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian. In the foreword, Joe D. Horse Capture, currently serving as Vice President of Native Collections and the Ahmanson Curator of Native American History and Culture for the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles, wrote, “Although there has been much criticism of the staging of Native subjects, I find their argument irrelevant. Instead, I view the photographs as a rare opportunity for Native people to see a part of their culture that has passed away.”

Reed only printed a limited number of images and sold a handful of photographic rights to National Geographic. He was working on a book and lantern series with his cousin Roy Williams when he died suddenly in 1934. Williams went on to give more than 2,500 lectures in the Midwest before his own death, when the collection fell to his heirs and went into storage.

Reed’s glass plates and personal artifacts remained locked up for decades until the Kramer Gallery in Minneapolis purchased the collection from the Williams family. They represented Reed’s work until retiring in 2010.

Shepherd of the Hills | Limited Edition Photograph, Metallic Print with Acrylic Laminate | 31.5 x 37.5 inches framed | c. 1913

In spring 2021, the collection saw daylight again when Jace Romick, a photographer and gallery owner from Colorado, purchased it. Romick was familiar with some of Reed’s work and had read Lawrence’s book. He still recalls seeing one of Reed’s most iconic photos, The Eagle, for the first time. “There was a raw beauty to it that completely struck me, looking at these men who seemed as much part of the landscape as the land itself,” Romick says.

“As a photographer, we hope our images will evoke emotions within those viewing them,” he says. “I believe that was Reed’s intent, and as someone who values our lands and our people as I understand Reed did, I want to honor that legacy with integrity.”

Romick’s prints of Reed’s work taken from his glass negatives hang in custom handmade frames alongside the apple-box size replica camera, journals, letters, and one of the only watercolors to survive Reed’s collection of artifacts.

Chief in Full Headdress | Limited Edition Photograph, Silver Gelatin Print with Acrylic | 38 x 46 inches framed | c. 1912

“This field of work is so dominated by Curtis, so to have another body of work from the same timeframe by another photographer is significant,” says Seth Hopkins, Executive Director of the Booth Western Art Museum in Cartersville, Georgia. “These are important images being shown at the gallery and offered to collectors of Western art.”

Romick feels an eerie sense of responsibility when he touches the glass plates he knows have survived arduous journeys on horseback more than a century ago. “I have a responsibility to honor Reed’s legacy and preserve his work for generations to come,” he says. “I hope those who see the genuine imagery in person see the pride in his subjects and sense the story he wanted to portray.”

Suzi Mitchell is a Scottish freelance writer who lives in Colorado with her three children, a spoiled dog, and a nonchalant cat. When not writing about artisans and architecture for publications on both sides of the Atlantic, she paints.

No Comments