09 Jan Orderly and Untamed

Tom Uttech was alone one evening on a lakeshore in Quetico Provincial Park in Ontario, Canada, doing what he says he does best these days: sitting still and looking for a long time. The brilliant sunset glow magnified the shapes of fallen pines along the shore, and on one of those logs, he noticed movement. It was a lynx. As Uttech watched, the graceful creature walked along the log, never seeing the man who did not stir. When the lynx reached the end, it jumped off and disappeared into a thick stand of young trees. “I knew if I moved, he’d be gone,” Uttech says. “The entire setting and the lynx — it was utterly, absurdly magical.”

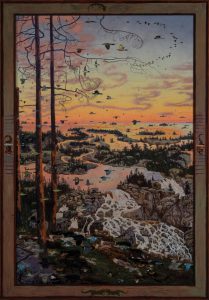

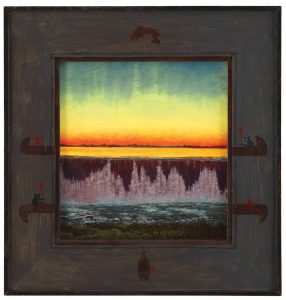

Totoganowan | Oil on Linen | 73 x 51 inches, with Hand-painted Frame | 2022 | Courtesy of the Artist and Alexandre Gallery, New York

This experience is what Uttech thinks of as becoming invisible in a wild place. It involves such obvious aspects as not wearing bright clothing or camping in a neon-colored tent. But more importantly, it’s the practiced ability to remain quiet and motionless, all senses engaged and receptive, not caught in distractions but extending complete awareness outside of oneself. “You enter a flow state where ‘you’ are not present,” he says. “That reveals things and permits experiences like this to happen.”

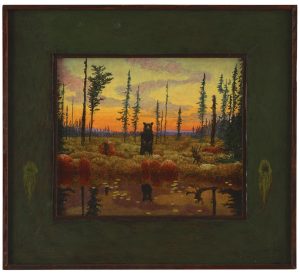

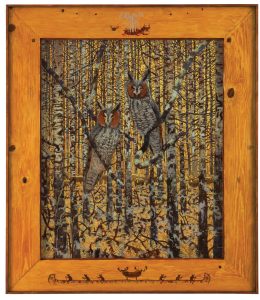

What is revealed may look something like Uttech’s paintings, where animals, birds, and even fish that tend to withhold themselves from human view are visible — sometimes in multitudes moving across the canvas, sometimes as a single creature staring at the viewer. Often, as in life, the longer one looks, the more one sees. Animals gradually become distinguished from rocks or tangles of downed trees. It’s almost always a crepuscular moment: not yet daylight or night, those in-between times when mystery is most alive.

Nin-Babishagi | Oil on Linen | 91 x 103 inches, with Hand-painted Frame | 2022 | Courtesy of the Artist and Alexandre Gallery, New York

Uttech has long been known for paintings that beautifully embody the haunting feeling of these moments. His inspiration is the wild Northwoods, which includes northern Wisconsin and Quetico Provincial Park, where he has spent countless days and nights, often alone. His paintings are not based on drawings or oil sketches created on site. Rather, they emerge from the part of himself that identifies with the essence of these places and sees them as metaphors for life. They can be familiar and comforting places, yet also unsettling and ultimately unknowable — which is what he loves about them.

Born in 1942, Uttech grew up in rural Wisconsin at a time when “country was pure country.” Sections of thick woods separated small farms, and wolves still lived in that part of North America. “We children were warned not to go into the woods. We might get lost and not come out,” he says. But the forest imprinted itself on his soul, as did one especially memorable experience as a young boy. Standing outside, Uttech watched a red-winged blackbird fly above a green hayfield. The combination of intense colors and the bird’s movement set in place “an absolute devotion to beautiful things and to nature and birds,” he says. He became a lifelong birdwatcher — part of how he learned to become invisible — and gained a passion for both the natural world and art. He does not remember a time when he wasn’t drawing. “Apparently, it took hold of me at a very early age and was the only thing that gave me comfort. If I was uneasy in my highchair, they’d give me paper and crayons, and I’d be happy,” he says.

Nin Sagisinotagon | Oil on Luan Plywood | 12.75 x 14.25 inches, with Hand-painted Frame | 2022 | Courtesy of the Artist and Alexandre Gallery, New York

During high school, Uttech filled his notebooks with drawings of activities that interested him — runners doing hurdles because he was in track or pictures of ducks because he enjoyed duck hunting. Although he had no exposure to original art, his obsession with drawing took him to the Layton School of Art in Milwaukee and later to the University of Cincinnati, where he earned a Master of Fine Arts.

When he entered art school, Uttech’s drawings were often landscapes produced from observation-based memory. Then, as an impressionable young painter, he found himself in the “urban, closed-loop art world,” attempting to fit into prevailing artistic modes. “As I tried to conform to what was expected, I felt more and more alienated from what I was doing, like someone else was doing it,” he says. “So, I gave up the idea of being an artist.”

Uttech was in his late 20s. Relieved of the self-imposed pressure of being a professional artist, he relaxed into life for a few years, spending time with his young daughter and taking camping trips to Quetico Provincial Park. But Uttech didn’t stop drawing or painting. Instead, the pop culture elements that had entered his work were replaced by forested landscapes containing mythical creatures, part human and part animal. He established a reputation with this imagery, which was out of step with much of the established art world but touched his own and others’ fascination with the mysteries of transformation.

Gradually, Uttech’s work evolved. The human figure disappeared. (Although his wife tells him that the nude woman with antlers still appears in his paintings, “but she’s hiding behind a rock.”) Early on, only one or two animals appeared on the canvas, staring at the viewer. Others were hiding or partially obscured. Soon he began adding more. And then many more: bird-filled skies and wolves, bears, and other furred animals, often in motion. Amidst trees and undergrowth and the frequent presence of water, they convey a sense of the richness of life in wild places. As Tory Folliard, owner of Tory Folliard Gallery in Milwaukee, puts it, “Tom’s paintings transport the viewer to the Northwoods, a place he dearly loves and one he portrays with magic and mystery.”

Minwabaminagwad | Oil on Linen | 31 x 27 inches, with Hand-painted Frame | 2022 | Courtesy of the Artist and Alexandre Gallery, New York

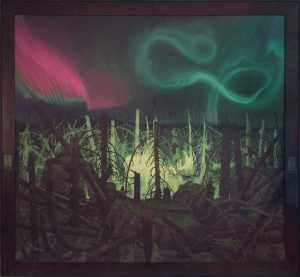

Having spent many nights in these places, Uttech understands the feeling behind early Indigenous peoples’ practice of entering their dwellings at dusk. “All the weird mysteries occur at dusk,” he says. “You have to be confident enough with the coming darkness to accept the mystery of transition. I like to paint that time. It contains so much inherent expressive possibility.”

For Uttech, imbuing imagery with an evocative mood and subtle connotations involves skillfully employing composition. He learned this at art school, particularly from studying the works of such masters as Da Vinci and Vermeer. He discovered how lines, arcs, and rhythms across the surface and the relationship between positive and negative spaces all combine to carry the weight of expression. And increasingly, Uttech says, his compositions are meant to suggest both physical places and the unity of life that he believes to be the deeper, unseen fabric of reality.

One way he visually communicates this concept is through recurring patterns and shapes. For example, in the night image Ganawaabandiwag, vertical trees are echoed in waterfalls and the flaring aurora borealis, while the swirl of other northern lights resembles the flowing shapes of water beneath the falls. “This is utterly true and happens,” he says. “It’s a metaphor for the unifying similarity of everything to everything.”

Phil Alexandre, the owner of Alexandre Gallery in New York City, says that Uttech’s work, “based on a most intimate and personal life-long understanding of the unspoiled natural world of his Northwoods, is as deep and spiritually powerful as Thoreau’s of New England.

Ganawaabandiwag (Northern Lights) | Oil on Linen | 73 x 79 inches, with Hand-painted Frame | 2003 / 2017 | Courtesy of the Artist and Alexandre Gallery, New York

All of Uttech’s paintings’ titles are derived from the Ojibwe language and loosely reflect the work’s meaning for the artist, who many years ago was gifted an Ojibwe lexicon created by a priest in the 1600s. And many years ago, Uttech began enhancing his paintings with handmade frames containing carved, burned, or painted images of plants, animals, insects, and birds. What surrounds the painting tells a separate but somehow related story, he says. “They might augment, complement, or complete each other. It makes room for imaginative images that would be inappropriate on the painting.” The painting is framed before the piece is finished, and Uttech works on both simultaneously. “Every time, it’s a struggle because the painting and frame contradict each other. But it often works. It’s part of everything being opposites at the same time,” he says.

Since the inclusion of Uttech’s paintings in the 1975 Whitney Biennial at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City, his work has been the subject of more than 40 one-person exhibitions and his paintings reside in the collections of the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas; the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.; and the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming, among many others.

Another aspect of Uttech’s world is the prairie restoration work that he’s done for more than 30 years. Leaving Milwaukee in 1987, he and his wife moved to an old, uncultivated farm in the country, where they have lived ever since. He began restoring the fields to their natural habitat, bringing back the extraordinary diversity of native grasses, wildflowers, insects, and small animals that thrive in and sustain such an ecosystem. He sees it as a relatively small but meaningful way of contributing to the earth he cares so much about.

Nin Mawiigon | Oil on Luan Plywood | 13.5 x 13 inches, with Hand-painted Frame | 2022 | Courtesy of the Artist and Alexandre Gallery, New York

Uttech’s hope is to have a positive, if incremental, impact on the environment by creating paintings that are visually interesting and emotionally engaging. If viewers spend time with them, recalling places they have been or that spark their imagination, perhaps they will be motivated to learn and care more about the natural world, he says. This could lead to lifestyle changes or other actions aimed at protecting the wild places they love.

For Uttech, that profound caring, and the inspiration for his art, is rooted in the experience of being so acutely alive and aware in a landscape that all distinction between himself and the place disappears. As he puts it, “I want my paintings to be about the feeling and experience at the moment of perception when every sense is open and magnificent beauty overwhelms.”

No Comments