06 Jul The Storyteller

A young cowboy stands on the brink of a beautiful but desolate landscape. His garb seems too large for his lanky frame, underscoring his youthful insecurity even as he appears to gain strength by draping an arm around his horse’s neck. Inky blue shadows and a lone tree accentuate his solitude as he sets out on his journey.

Anyone with an ounce of empathy and imagination will likely find themselves drawn irresistibly into Young But Not Afraid, one of four paintings Eric Bowman created for his 2019 debut in Masters of the American West at Los Angeles’ Autry Museum. “That was my first, quote ‘Western’ museum show, and a very important one,” he says of the milestone, which placed Bowman amidst the company of such well-respected names as George Carlson, Bill Anton, Howard Post, Tim Solliday, Dean Mitchell, and Logan Maxwell Hagege. And it all took place at an institution where the permanent collection includes works by Maynard Dixon and Frank Tenney Johnson, two Western giants of the last century whom he reveres.

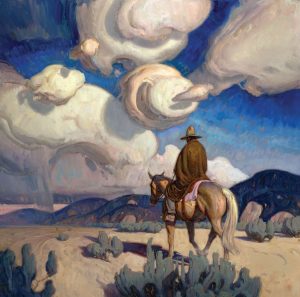

Into the Mystic | Oil on Canvas | 40 x 40 inches | 2020

Bowman has been in the event every year since, consistently selling all his paintings. Such an achievement — together with repeated participation in other top shows, including Prix de West at Oklahoma City’s National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, Night of Artists at San Antonio’s Briscoe, and the Coors Western Art Exhibition in Denver — surely mark Bowman’s arrival as a first-rank artist.

Yet, it’s essential to note that the painter, now in his early 60s, had already forged a formidable career as an advertising illustrator with clients including Land Rover, AT&T, and Time magazine. Such sterling credentials belie an even more important fact. “I never went to art school,” Bowman says. “I basically taught myself.”

Autumn Tapestry | Oil on Canvas | 36 x 46 inches | 2023

His self-driven education was nonetheless thorough. Growing up in the Southern California town of Covina, he always loved making art and watching classic Western TV shows and movies. “My friends and I played a lot of cowboys and Indians to entertain ourselves,” he says. Bowman’s innate drawing skills earned him a reputation as the class artist. He dreamt of attending the respected ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena. But, after being told he’d first have to complete a two-year general-education degree, he instead plunged headlong into earning a living with his talents.

Bowman learned layout, design, and paste-up in the art department of a company owned by a friend’s father. He then worked as a freelance graphic artist designing logos and t-shirts, drawing editorial cartoons, and airbrushing custom surfboard art. Eventually, he moved to Portland, Oregon, where he’d finished high school following his parents’ divorce. For a few years, he was a freelance graphic artist with a workspace in shared commercial art studios. “I learned a lot just watching other artists and asking questions,” says Bowman. He visited galleries and museums regularly and built and read an extensive collection of art books. “And then there were just years of trial and error,” he says. “I’ve met a number of artists who went to prestigious art schools and didn’t learn some of the things I did through the school of hard knocks.” Eventually, after marrying his wife Debbie in 1992, Bowman moved his studio into the first home they bought. His career continued to flourish.

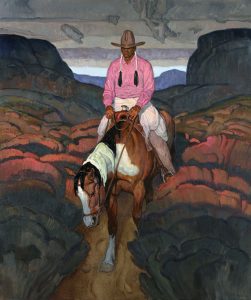

New Mexican | Oil on Canvas | 50 x 42 inches | 2023

Through his dedicated self-education, Bowman developed a rich appreciation for artists of the past, a deep knowledge that would ultimately come to express itself through his paintings. In his daily work, Bowman strived to emulate stars of the so-called Golden Age of Illustration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including Dean Cornwell, Harvey Dunn, Harold von Schmidt, and N.C. Wyeth, “all of whom did a ton of Western-flavored material,” he says.

He also gained inspiration from great early 20th-century American painters, including the Tonalist Western landscapes of Maynard Dixon and the faithful, romantic way the Taos Society of Artists captured the light and landforms of Northern New Mexico. Then there were the “famous fine artists outside the Western genre,” including English painter Frank Brangwyn, Czech Art Nouveau painter Alphonse Mucha, “and a whole bunch of Russian guys whose names I can’t even pronounce let alone remember. I go through these periods of infatuation and then get over it and move on to the next dead guy that I discover.”

Four Seasons | Oil on Gesso Panels, 36 x 20 inches each | Mounted in Quarter-Sawn Oak Screen, 69 x 97 inches | 2023

Bowman reflects for a moment. “I believe thoroughly that fine art peaked 100 to 150 years ago. It demanded a higher standard back then.” He hesitates to blame modern mass media, “though it certainly watered things down. Before it, artists and illustrators were like rock stars. Middle- and lower-income families hung their mass-produced imagery on the walls of their homes.”

A major career turning point came in 1998 when, during a visit to an old friend in Pasadena, Bowman was introduced to the respected local artist Tim Solliday. The two men bonded, and when Bowman expressed his interest in pursuing fine art, Solliday advised him to begin plein air painting — adding that, if he applied himself, it would take about five years to make the transition. While still earning a living as an illustrator, Bowman began diligently painting outdoors, and in 2005, he started winning awards in plein-air shows. Eight years later, he became a full-time fine artist.

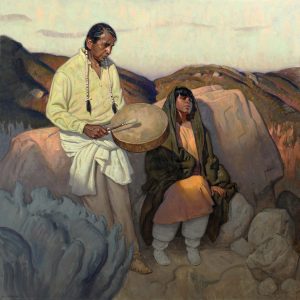

Lamentation | Oil on Canvas | 48 x 48 inches | 2023

Bowman now works in a 2,150-square-foot Quonset hut-style studio behind the home he, Debbie, and their daughter Lily, now 17, moved to in 2002 in the Portland suburb of Tigard. The structure provides ample space to work on multiple canvases at once and store his art supplies and books.

He continues to forge ever deeper connections with viewers. Take, for example, his recent Lamentation, depicting a Pueblo father solemnly beating a drum for his grieving daughter. “He’s there, solid as the rock she is sitting on, as he chants a prayer,” says the artist. Every element of the composition and its execution — from the way shadows partially enshroud the young woman while sunlight illuminates her father, to the sense of anticipation built by the drumstick about to strike the drum — epitomizes the artist’s power.

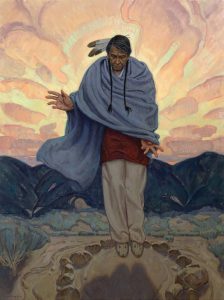

Transcendence | Oil on Canvas | 48 x 36 inches | 2023

Bowman is also tackling even more ambitious projects, like the recent Four Seasons, a quartet of paintings, each 36 by 20 inches, that fit into a custom-built, classic Craftsman-style folding screen. Exhibited and sold in this year’s Prix de West, it captures autumn, winter, spring, and summer through portrayals of Native American figures in iconic Western landscapes. “I’ve never done anything like this before,” he says of the undertaking, which, in its Arts-and-Crafts aesthetic, harks back to an era when, Bowman believes, fine art was at its peak.

Such an ever-creative spirit continues to drive the artist. “As far as ideas go,” Bowman says, “I don’t get too anxious worrying about what’s next. I just let things happen organically. While I’m working on one painting, the next idea is already formulating in my mind.”

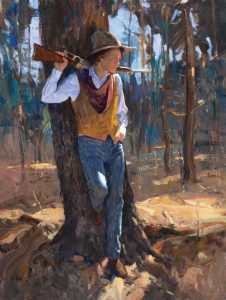

Waiting for the Drivers | Oil on Gesso Panel | 16 x 12 inches | 2019

Bowman is represented by Astoria Fine Art in Jackson Hole, Wyoming; Mark Sublette Medicine Man Gallery in Tucson, Arizona; and Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Los Angeles, California, where his large solo show of 15 paintings opens on September 9. His work is also on view at the 51st annual Prix de West Invitational Art Exhibition & Sale at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum through August 6.

No Comments