06 Sep Perspective: THE 100-YEAR-OLD RADICAL

Rudolph Schindler’s house in West Hollywood doesn’t appear on any of the Hollywood star maps, yet it’s among the most important and revolutionary residences in America. While the likes of Lucille Ball or Liz Taylor never lived in the home, the stars of design and the intellectual world of the 1920s and 30s visited — from Frank Lloyd Wright and Richard Neutra, to Igor Stravinsky and John Cage.

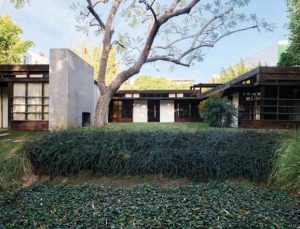

Upon arriving at the dwelling that the architect and his wife Pauline built in 1922 on Kings Road, visitors discover the house concealed by towering hedges; and only upon coursing the 200-foot driveway does the low-slung Japanese-esque residence reveal itself, modestly. While it may not have the immediate star-quality resonance of other iconic American houses — Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House, or Philip Johnson’s Glass House — a visit to the Schindler House tells a distinctive, enduring story about American residential life, as well as a poignant one about the couple who built it.

Architect Rudolph Schindler [1887–1953] designed a revolutionary house in West Hollywood in 1922. Photo courtesy of the R. M. Schindler papers, Architecture & Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara

“Every time you slide open a glass door and walk outside to your yard in Los Angeles, that very act owes a small debt to the Schindler House,” says Oliver Furth, a noted Los Angeles interior decorator and cofounder with his partner Sean Yashar of Furth Yashar & ______ (sic), a self-described “roving gallery” that “showcases artists and designers who create works that elude categorization,” the blank space in their name indicating an “openness to ideas,” Furth explains.

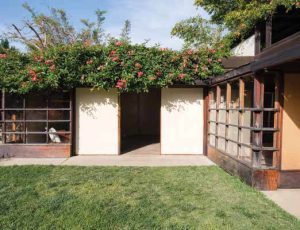

A defining feature of the house Schindler designed for himself and his wife Pauline is the way the interiors meld seamlessly with exterior garden areas that function as rooms in themselves.

As a native Angelino, Furth grew up just blocks from the Schindler residence, recognizing even as a boy that its aesthetics reflected radical social and architectural conventions, concepts that would influence his future work as a designer. Some of those ideas are articulated in Furth’s forthcoming book, OP! Optimistic Interiors (Rizzoli).

The house was conceived by the Austrian-born Rudolph Michael Schindler [1887-1953], along with Pauline (who received little official recognition for her crucial role in its design), and also by Clyde Chance, a building contractor employed by Schindler, who moved into the house with his wife and child. Demarcated living areas, shaped as loose Ls, insured privacy for the two families. Now more than a century old, the residence embodies still-cutting-edge radical design.

Schindler even designed outdoor “sleeping baskets,” as he called them, on the roof (visible in the photo directly above), to foster the interplay between living inside and sleeping outside.

Adhering to Schindler’s expressed desire to create a structure whose “shape of the inner room defines the exterior of the building,” the house is, perhaps, the precursor of the California ranch house — a one-story, open-plan dwelling, with ready access to patios and gardens that function as outdoor rooms. It also predated the Case Study Houses, a building program instituted after World War II in Los Angeles to provide affordable, easy-to-construct houses for the middle class.

Pauline, a social activist who had spent time as a social worker at Chicago’s progressive Hull House, envisioned a residence for herself and Rudolph that would dismiss class distinctions in its sheer unpretentiousness, while functioning as a meeting place where friends could come and go freely.

Horizontal bands of windows, demarcated by redwood frames, capture the property’s views. Photos courtesy of the MAK Center for Art and Architecture

The house is maintained as a by-appointment-only museum by the MAK Center for Art and Architecture, L.A., a nonprofit that oversees structures by the many Austrian architects who practiced in Los Angeles in the 1920s and 30s. MAK references their parent institution: the MAK — Museum of Applied Arts (Museum für angewandte Kunst) in Vienna.

Visitors to the Kings Road House enter through the kitchen door; its diminutive width and height are of a medieval scale. The experience involves going from bright Southern California sun to rooms that are dim, still, and humid, even with their Shoji-like canvas panels open wide to patios and gardens. Blocks of sunlight stencil across concrete floors. Door jambs and ceilings are low, fostering both an intimacy and, to some, claustrophobia. The house’s concrete walls — 4-by-8-foot sections that had been cast in-situ — remain unadorned. Each 3-inch gap between the sections (the interstices) is filled with a fixed pane of plexiglass (originally glass) that teases in light and frames views.

This detail of the Kings Road house shows a redwood element that acts as a sun-shading device.

Schindler left his native Vienna in 1914, just as the fin-de-siècle era of the city was diminishing at the outbreak of World War I. At age 26, he moved to New York, drawn there by the “fascination with the raw power of American cities,” as James Steele writes in his monograph on the architect, R.M. Schindler: An Exploration of Space (Taschen), that details 31 houses and apartment buildings he designed in and around Los Angeles.

After studying under Frank Lloyd Wright in Chicago, Schindler and Pauline were lured to California in 1920 when the young architect was enlisted by his then employer/mentor to oversee the construction of oil heiress, arts patron, and feminist Aline Barnsdall’s Hollyhock House, one of Wright’s masterpieces. Like so many creative people of the era in all disciplines – from architecture to classical music to literature and painting – who found themselves in Southern California, Schindler never left Los Angeles to live elsewhere, calling it, according to Steele, “an earthly paradise.”

Furth, who had mounted an exhibition in 2018 at the Kings Road House highlighting four contemporary makers of art in various media, chose the residence for the show because it represented the very ethos that has long defined his city. “It’s the million-dollar question to which there is no definitive answer,” says Furth about why Los Angeles developed into what many consider America’s most creative city. “The most exciting architecture has, and still does, come out of California. There is something magical about sunlight, the air, that encourages creative, free-thinking people like Schindler and his wife Pauline.”

Although outdoor fireplaces and fire pits are now common features of homes in Los Angeles, Schindler was among the first architects to incorporate them as details. Most of the large concrete walls were cast in place. Photos courtesy of the MAK Center for Art and Architecture

Although the Schindlers built the house as a couple, they separated in 1927, later living together there as a divorced couple, an arrangement facilitated by a dividing wall along the central patio. Perhaps to taunt her minimalist-obsessed, palette-limited ex-husband, Pauline had painted the interior walls on her side a bright pink, much to the annoyance of Rudolph. Steele quotes a letter Schindler sent to his estranged wife, upon learning of the hue on the other side of the wall. Referring to her as “Madam,” Schindler wrote: “Kings Road was built as a protest against the American habit of covering their life and their buildings with coats of finish material to fool the onlooker about their common base.” For the many years they lived under the same roof, until Rudolph’s death in 1953, they corresponded solely by (mailed) letter.

Of the more than 30 houses and small-scale apartment buildings Schindler designed in and around Los Angeles, the Fitzpatrick House (completed 1936) remains among the freshest and most timeless.

Fireplace flues are articulated by copper sheets, folded against the walls with neat creases, their shine and hammered textures decorative details. The scorched and blackened concrete floor beneath the hearthless fireplace evokes a prehistoric cave dwelling where one wouldn’t be surprised to find a charred mammoth’s bone. Schindler wrote in a letter to his in-laws, shortly after a holiday in Yosemite, of his desire to create “a social ‘campfire’ affair” in the house, whereby cooking could be done tableside, akin to a “camper’s shelter.”

Intersecting planes, expanses of mullionless windows, and dramatic overhangs imbue the house with a contemporary identity.

For those who might still feel challenged by the austerity of the house, its real form and beauty lie beyond the concrete walls. In keeping with the house’s relationship to the outdoors, two minimally articulated structures on the roof were designed by Schindler as “outdoor sleeping baskets” — at a time when it was still possible to see stars (the ones in the sky, not on the screen) in central Los Angeles. The alfresco rooms seduce visitors, melding with multi-level terraces and precisely demarcated sunken gardens. It is from these outdoor vantage points that the house thrills — with its long-reaching intersecting planes, redwood roof beams meshing with bold, vertical chimneys, and an uncompromising austerity.

The house takes special advantage of its precarious position atop a slope of Laurel Canyon. Photos courtesy of the MAK Center for Art and Architecture

Architectural pilgrims regularly seek out Schindler’s many other residences in the city, though his own on Kings Road is the only one open to the public. The 1925 cube-like How House in Silver Lake is noted for its Wrightian planes and windows. The 1926 Lovell Beach House in Newport Beach is one of the earliest examples of beachfront homes raised on stilts, a “typology,” as Steele writes, that is now “commonly accepted in Los Angeles.” Furth lives near the 1936 Fitzpatrick House in Laurel Canyon, which he cites for its “beautiful sculptural quality. I see people walking by it, driving by it, often mistaking it for a classic 1960s, Mid-century Modern masterpiece, but it predates that era by decades. Schindler was so ahead of his time.”

Rudolph Schindler’s houses endure, readily adapting to families who live in them today. A visit to his Kings Road House is a central stop along the timeline of modern residential architecture, for it is a home lived in and designed by a Hollywood star.

David Masello writes about art and culture. He is currently executive editor of Milieu, a national print magazine about interior design and architecture, and is the author of three books about art and architecture.

No Comments