07 Nov Reclaiming Tradition

There was a moment this past August at the 101st annual Santa Fe Indian Market when textile artist Melissa Cody, who served as the textile classification manager for the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts, paused and thought about her career’s influence on other Diné (Navajo) weavers.

“When I started entering these art shows and museum shows, all the other weavings were done in a traditional way,” says Cody. “But this year, as I looked around, everything was contemporary, pushing the boundaries. Even in the ones done in a traditional style, there was a little twist.”

One only has to see the arc of Cody’s weaving career — and what is happening right now — to understand why she has influenced the nearly 200-year tradition and how her impact is being recognized and celebrated.

Ongoing through January 15, 2024, Cody’s work is included in The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art by Native Americans at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., curated by another groundbreaking Indigenous artist, Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith (Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation). In late September, Cody was one of 39 artists in Made in L.A. 2023: Acts of Living at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. And, in October, her first international solo exhibition, Melissa Cody: Webbed Skies, opened at the São Paulo Museum of Art in Brazil. After its South American run, the exhibition will open at MoMA PS1 in New York City in spring 2024.

The history of Diné weaving is a long and complicated narrative, sad yet beautiful, full of struggle and endurance. Early weavers were typically subjected to the whims of white trading post operators who kept the artists in the shadows, dictating designs and styles for them to weave based on Eastern trends and tourist wishes, and only paying them a small fraction of the actual selling price. For an incredibly creative and time-consuming art form, creativity was not encouraged. Weavers were forced to follow the designs of whatever trading post was geographically close to where they happened to live; Two Gray Hills, Red Mesa, Ganado, Chinle, Burnt Water, and Wide Ruins became the accepted names of these styles based on their locations in New Mexico and Arizona. The weavings — beautiful, elegant, and intricately designed — are a testament to the skill and craftsmanship of these early artists, despite the fact that self-expression was rarely encouraged.

I am Navajo Barbie | Wool Warp, Weft, Selvedge Cords, and Aniline Dyes | 19 x 17 inches | Courtesy of the Artist and Garth Greenan Gallery

Cody was born into this tradition when she entered the world in No Water Mesa, Arizona, on the Navajo Nation. She is a fourth-generation weaver. Her grandmother Martha Gorman Schultz, her mother Lola Cody, and her aunts Lena Williams and Marilou Schultz taught her to weave beginning at the age of 5. But early in her career, Cody knew she wanted to change tradition and bring back power to weavers, to the women she watched pulling and dyeing the wool, rolling it against their thighs, creating wefts and warps, fringed, twined, and hemmed.

“I was never a newcomer trying to change the game; I was born into that tradition, and other weavers saw me build my career from a child to adulthood and that afforded me the wiggle room to explore and expand on the foundation I built throughout my career,” Cody says. “I wove out of necessity, and all along, I wanted us weavers to reclaim the market and the designs, reclaim how we projected ourselves, reclaim the way we approach the art market, reclaim the way we sell pieces and show at museums. I wanted the weavers to reclaim all of that.”

Cody sees this early history with the trading posts, the tourist trade, and the expansion of the railroads as dominating the stories of those early weavers. “For such a long time, weavers were afraid to do anything outside the box,” Cody says. “It became stagnant. The middle man wouldn’t buy anything that would stray from textbook and classic designs. So I wanted to make weaving appealing to the upcoming generation, for it to not just be seen as old people’s work anymore.”

She didn’t just work outside the box. She broke it wide open for generations of textile artists who understood contemporary art and wanted to express themselves differently. Today, a whole new generation of weavers is working and inspired by what Cody has accomplished.

One of Cody’s early series from around 2011 was based on her father’s struggles with Parkinson’s disease. A piece from that series presently resides in the Minneapolis Institute of Art’s collection, titled Deep Brain Stimulation. In this weaving, Cody created the illusion of three dimensions within a two-dimensional textile. Her designs were inspired by the radiation treatments meant to help her father develop new neural pathways to manage the disease.

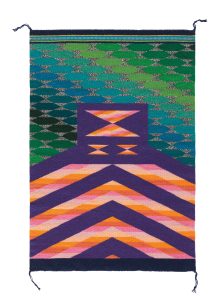

Under Cover of Webbed Skies | Wool Warp, Weft, Selvedge Cords, and Aniline Dyes | 36.75 x 25.25 inches | 2021 | Courtesy of the Artist and Garth Greenan Gallery

“I wanted them to be more subject-based, less about aesthetic iterations and more about personal testament,” says Cody. “I wanted to talk about those issues and be more theme-focused. Before, Navajo weaving was design-based, mapping out geometric patterning, but now I’m thinking what the overall piece would be about, then mapping out the logistics.”

Another early piece, Weaver’s Union 408, incorporated found objects, including caution tape. The weaving is again an homage to her father Alfred, and Cody found the materials she used in the equipment and toolboxes he worked with in construction. Alfred built her looms throughout Cody’s career, and for this piece, he built a shadow box to frame the textile. Weaver’s Union 408 now resides in the permanent collection of the Hilton Santa Fe Buffalo Thunder resort.

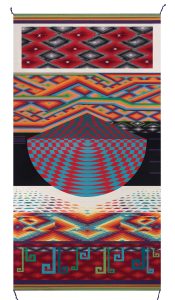

World Traveler | Wool Warp, Weft, Selvedge Cords, and Aniline Dyes | 90 x 48.875 inches | 2014 | Courtesy of the Artist and Garth Greenan Gallery

“I want people to understand that we, as Indian people, are not stagnant,” says Cody. “There can be traditions made by the current generation as well, and Native artists should be able to tell our own stories through our own artwork. For me, I had the foundation; it was put in place by my mom and grandmothers, and through conversations with my elders, I was able to expand upon these weavings. They all signed off on my ideas; they gave me their blessings to move forward with my projects, go off into left field, and just push what can be made on the loom.”

In a full-circle moment, Cody’s work has started to influence those who originally taught her. Her mother has won many awards throughout her career with her Burnt Water, Two Gray Hills, and Wide Ruins designs. But now, she’s created weavings with abstracted landscapes and breaking lines of symmetry. She, too, has become more fluid in her work.

And, just recently, Cody received a textile in the mail from her 90-year-old grandmother. “I sent her home with new materials, and she made a brand new piece with 20 colors of Germantown yarn,” Cody says. “She’s creating new Germantown textiles and said she feels like a new breath of life has come into her work.”

For Cody, it’s not just succeeding but helping others do so as well. “I want to get to the next level. I want my career to be exciting, and it’s more exciting when others come along for the ride. And now I have kids, and I wonder what their future will be and whether it will include textiles. I want to open that door for them as well; I want them to explore that part of their creative selves. And I want to show them that creativity can give you a fruitful life in this current place in time, living right here where we do.”

No Comments