04 Jul Collector’s Notebook: Art Market Insights

Prints hold an alluring appeal for seasoned and brand new collectors. For those just starting to dip a toe into the art market, prints are an easy way to buy works by substantial artists at prices that won’t stop your heart. In a similar manner but to a different degree, experienced collectors find prints a fabulous way to acquire works by deceased artists whose paintings sell at auction for staggering sums.

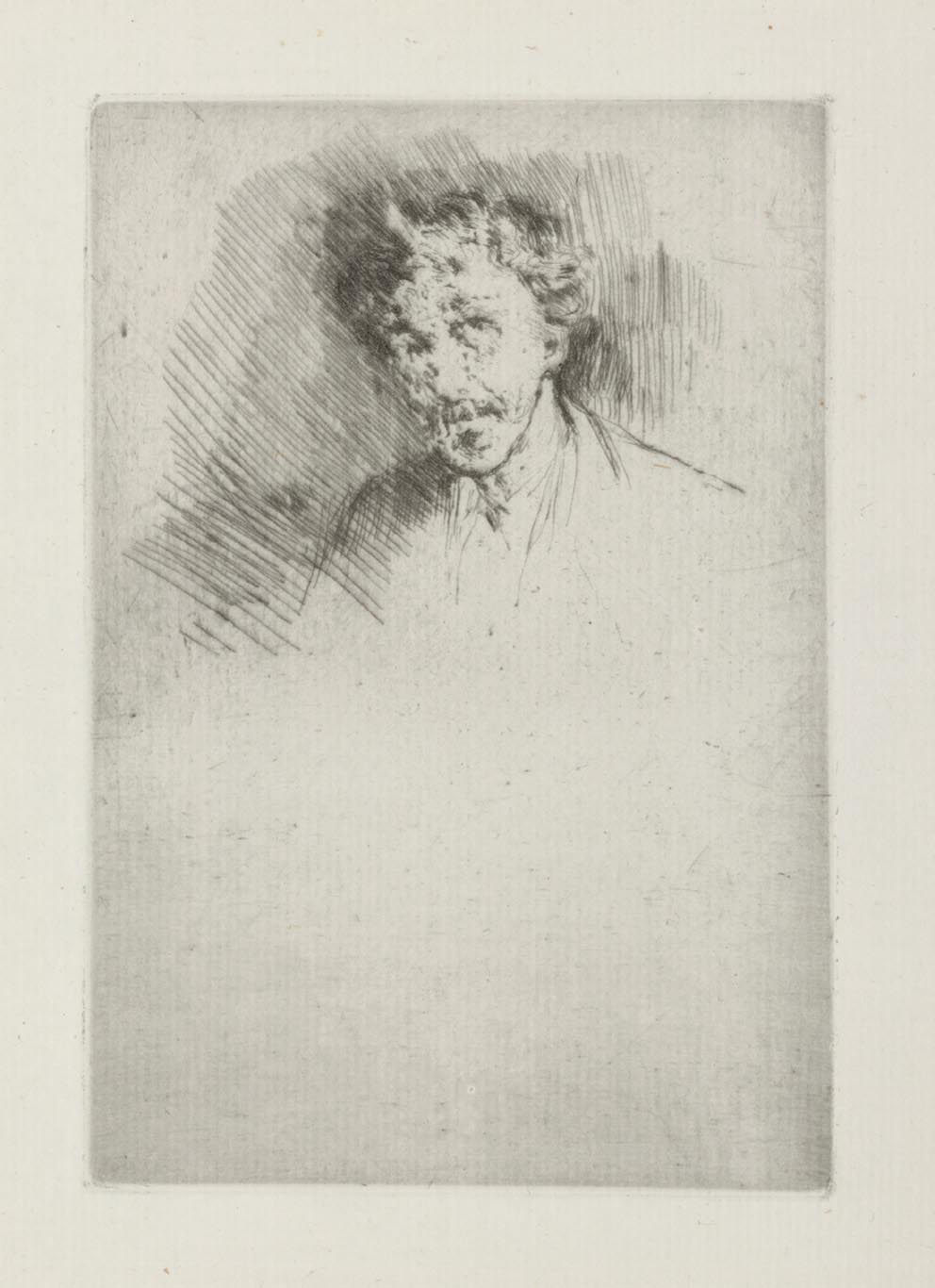

Consider, for example, the works of James Abbott McNeill Whistler [1834–1903]. Whistler’s paintings are rarely for sale, but his prints frequently appear on the secondary market. That’s because, during his lifetime, Whistler made more than 400 etching and drypoint plates and some 150 lithographs, which means there are multiples of those 550-plus images out there in the world, many selling for $1,500 to $28,000. Compare this to the sale of an oil painting by Whistler. In 2021, Christie’s sold a 9.5-by-6.63-inch work titled Whistler Smoking for $1.2 million. It comes down to the basic principle of supply and demand: Whistler’s paintings are scarce, but his prints are not.

Man vs. Machine

The technique of duplicating images dates to the Sumerians (c. 3000 BCE). They engraved designs and cuneiform inscriptions on cylinder seals (usually made of stone), which, when rolled over soft clay tablets, left relief impressions. It’s speculated that the Chinese produced a rubbing in the 2nd century CE, but the first authenticated woodblock prints were Buddhist charms printed in Japan and distributed between 764 and 770 CE.

Since then, many other printing processes have been added to the mix, opening up the art form of “original multiples” and making it affordable for both artists and collectors. When looking at prints, there is an important distinction: manual versus mechanical, human versus machine. It’s good to start with a little background to determine the difference.

Prints, in their various hand-pulled forms, are artworks in themselves and are created using different means. The oldest prints were reliefs, which involved carving a surface with raised designs, covering it with ink, and placing paper on top. Then, pressure was applied to transfer the ink onto the paper.

The second oldest form is intaglio, meaning “incising or engraving.” In this method, an image is etched into a plate, and ink is pushed into the engraved lines. The surface is then wiped clean, and paper is laid on top, followed by blankets. Then, the whole assemblage runs through a press with heavy pressure, causing the paper to absorb ink from the incised lines. This process leaves a plate mark when the paper dries.

The third process, which is more recent, is known as planographic or surface printing — lithography. This is done on a litho stone or flat metal surface. The idea here is that water and oil don’t mix. An image is created on a smooth surface using a greasy substance such as oil, fat, or wax, creating a water-repellent area. The surface is then treated with a solution of gum arabic and weak acid, which ensures that the background becomes water attracting. During the printing process, the surface is first moistened with water, and an oil-based ink is then rolled over the surface, adhering only to the greasy areas and being repelled by the wet. Next, paper is set on top, and the work is run through a press.

Screenprints and monotypes are the most recent printing processes. Screenprints are essentially made using silk screens on which the artwork’s image is masked off. Ink is pulled across the screen so that it falls through onto a sheet of paper below. Many layers of colored ink are used to create one image, and, as a result, you can usually see the ink laying on the surface more readily than in other printing processes. Monotypes are “mono” because there is only one work — technically. The artist does a painting on a flat surface, such as plexiglass or copper; then, damp paper is laid on top of the painting and the whole thing is run through the press. A mirror image is pulled, leaving a ghost image behind. The artist can go back over the ghost image and change it, reink it, and run another print, though it will be noticeably different, thus a new monotype. And, just to make this all a little more challenging, lots of these processes can be combined to make an image. All in all, printmaking is deceptively complicated and possibly one of the most underrated art forms.

The final category of prints are mechanical. Mechanical prints, such as giclees, are reproductions — facsimiles — of original works. Giclee is a French word meaning “to spray,” which refers to the inkjet process of spraying ink on paper to reproduce art. Machine-made off-set lithography, which is how this magazine you are reading was printed, and giclees are the most common, which brings us to the downside of printmaking for artists.

More Isn’t Always Better

Supply and demand play into pricing art.

Paintings are singular. Hand-pulled prints come in multiples (except monotypes) and tend to have lower print runs because the plate or silkscreen wears out. With woodcuts, the artist may have one or two plates for an image, but that plate is run through the press multiple times and for each new color, with some works having upwards of 20 color changes. During this process, the woodblock is further carved away so that, by the end of production, the plate is destroyed.

Machines that make prints, however, do not wear out. And beyond the photographer who took a high-resolution photo of the art and the press that oversees the printing, there isn’t any human contact.

Here’s why more isn’t better. An artist can flood the market with reproductions of individual paintings. For new artists scrambling to pay rent and buy groceries, the promise of making a hundred bucks off a giclee sounds like salvation. You can practically sell them off your website while you sleep! What could possibly go wrong?

While these prints are incredibly accurate reproductions of paintings, they create a troubling side effect: artists start to compete against themselves. In the art market, at a certain price range, many art buyers can’t tell the difference between an original and a giclee and think, “Why pay more when the print is so good?” Established collectors, however, know this is the equivalent of buying a Farrah Fawcett poster: Totally rad, dude, but not the real thing.

So, when it comes to prints, scarcity and the human touch create value. Mechanical prints are beautiful but won’t hold their value. The savvy print collector looks for works pulled by specific master printers at certain presses that coincide with the era of the artist. Craftsmanship counts: You want to see the hand that built it.

If you want to collect prints, we highly recommend learning more about the various processes. Bamber Gascoigne’s book How to Identify Prints: A Complete Guide to Manual and Mechanical Processes from Woodcut to Inkjet is invaluable. Visit some print fairs to see works up close and ask experts to explain what you’re looking at and the pricing. There are myriad issues to consider before buying prints, but it all starts with identification. Once you invest the time to learn about prints, you can find valuable pieces at estate sales, consignment shops, and antique stores.

A Diamond in the Rough

Telltale signs you’re looking at a print with value

Production: Rule out mechanical prints by looking for a dot matrix. You might need a magnifying glass (a loop with 4x magnification) to see the dotted pattern. It will look a lot like the Sunday comics in newspapers.

Plate Impression: You can easily see where an intaglio plate left an impression around the outside of the image. These images are almost always one color — black or sepia. If there is color, that may indicate that the artist painted on the print, making it a unique work of art.

Chroma: Color could indicate lithography, serigraphy, or mechanical printing. Sometimes, if you look from the side of a print, you can see a layer of ink floating on the surface. This would indicate a monotype, lithograph, or serigraph. Look for the dot pattern when in doubt.

Signature: If you see a print with two signatures, one within the painting and another on the white paper border, it’s most likely a high-resolution photo of a painting — signature and all — that was run on a mechanical press. The artist then signs and numbers these pieces of paper, indicating it’s a reproduction of the original. With hand-pulled prints, the artist’s signature will be written in pencil, usually along the bottom of the image. There will also be a title, often centered below the image, and edition number.

Edition: With hand-pulled prints, the first edition number is the identification of the piece, and the second number is the total number of prints available. Look for low numbers. If the number is above 100 — say, 1,200, for example — those are mechanical prints. No plates or screens can hold up to that amount of re-inking and press runs.

Notations: Look for prints with AP, PP, and HC. Each has a distinct meaning. “AP” stands for Artist’s Proof. These prints are reserved for the artist’s personal use and are often considered more valuable due to their rarity and direct connection to the artist. “PP” stands for Printer’s Proof. These proofs are given to the printer involved in the production process and are similar in status to artist’s proofs but are specifically intended for the printer’s use or collection. “HC” stands for Hors Commerce. This term translates to “out of trade.” They are not meant for commercial sale, and instead these prints are often used for promotional purposes or given as gifts.

Condition: When selecting prints, inspect them carefully. You don’t want to buy things with tears, creases, foxing, or discoloration. But some condition issues can be corrected, so it’s worth asking a conservator.

Curator and writer Rose Fredrick shares her extensive knowledge about the inner workings of the art market on her blog, The Incurable Optimist, at rosefredrick.com.

No Comments