04 Jul REVIVING WILL JAMES’ SPIRIT

What is the true West, and why does our search for an answer matter today?

Will James straddled a fine line between real and imaginary, fact and fiction, the mythological and genuine article. He traversed, as an artistic underdog, the boundary between invention and reinvention, often being on the move to stay ahead of the past.

A Nevada Cowboy article covers the life and lore of famed cowboy illustrator and author Will James

According to Bill Rey, owner and partner of Claggett/Rey Gallery in Edwards, Colorado, James represented a version of the American West that millions still want to believe in. Earlier generations escaped into James’ world on every page he ever wrote, on matinee screens where his storylines represented an escape, and in every nuanced outline of a horse that inhabited his memory — gestural forms he mastered as well as anyone else, including better-known giants of Western art — because he drew from the heart.

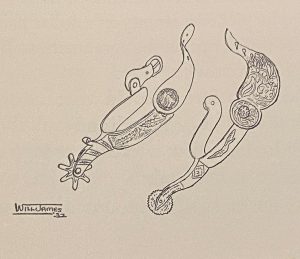

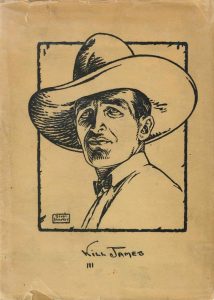

This illustration, titled Spurs, is one of as

many as 1,500 drawings James created during his career.

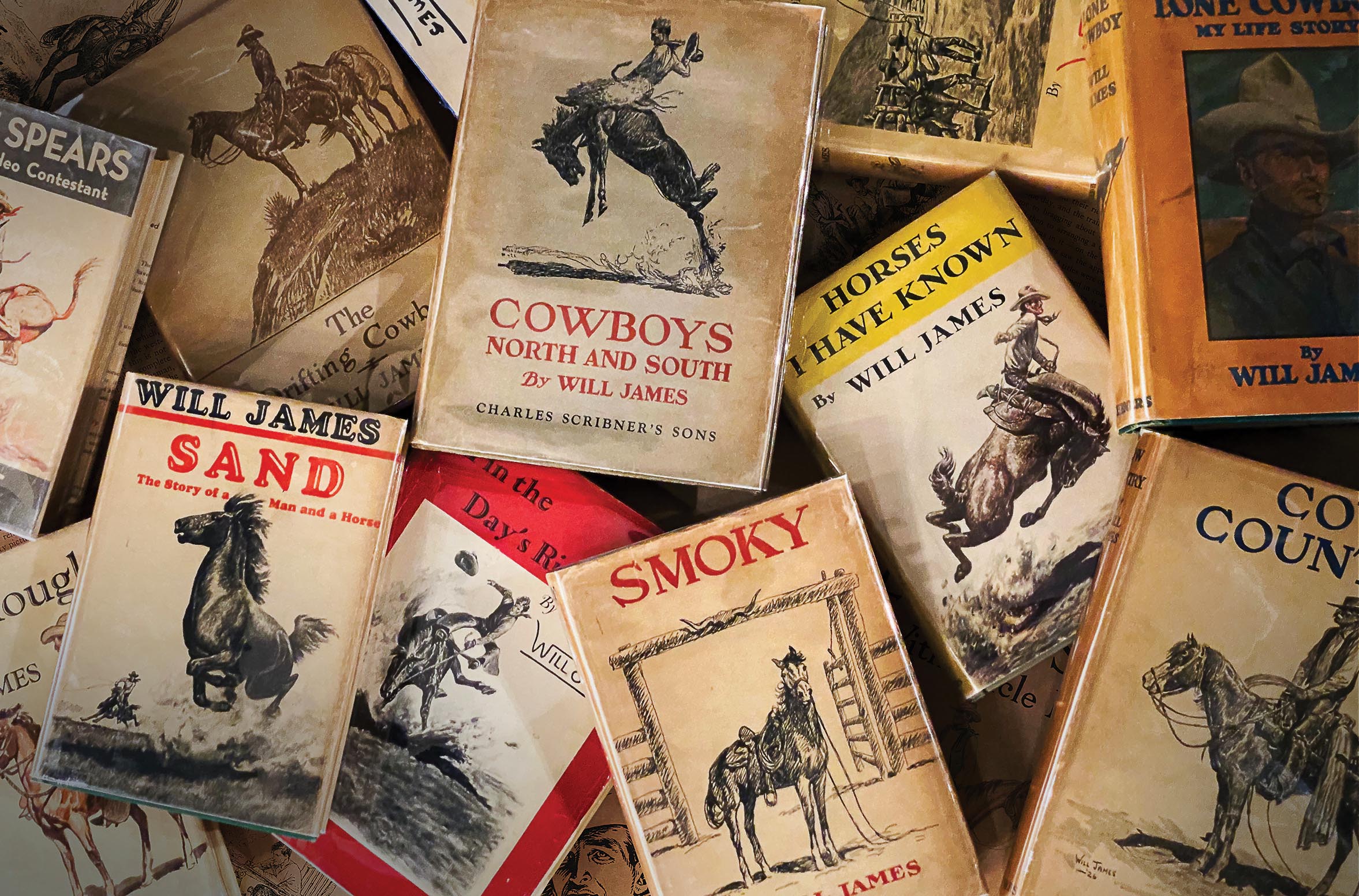

In August at Claggett/Rey Gallery, something of a Will James revival is being staged. Entitled Cowboys North and South, the show — which will be up the entire month — commemorates the 100th anniversary publishing of a James’ book by the same name. Pure and mischievous in its intent, the happening brings together an enigmatic assemblage of fine art created not only by James [1892–1942] but inspired by him. Painters and sculptors past and present, photographers, poets, makers of fine Western jewelry and textiles will all have works represented. At least 100 objects will be in the show. It is Rey’s way of paying homage to what he calls “the unifying presence James had at a crucial time in our country’s history.” That’s not dissimilar, he says, to where we find ourselves now. “I believe art that reminds us of where we’ve been can serve as a compass for reaching the better place we’re heading.”

It’s a strange thing, perhaps, to ponder how legendary, though imperfect, figures from our past sometimes have to go away for a while or even be forgotten before their talents can be appreciated again. Rey is firmly convinced that the real backstory of James, cast into fresh light, is so much richer than the fictional persona he invented.

Whatever the appropriate antonym describing what “a Will James retrospective” might be, the idea came to Rey a few years ago when he was enlisted as a special guest curator for an exhibition at the Calgary Stampede. He poured over a lot of historic and contemporary works to fill that acclaimed event, and he discovered that so many Western artists made references to James, particularly his reputation for communicating the spirit of horses.

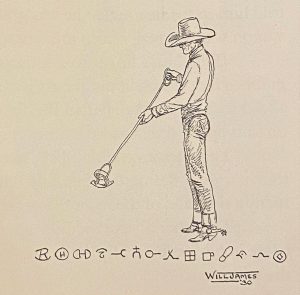

Cattle Brands, an illustration by James, shows the artist’s fine linework

Although James as a “cowboy artist” carried forward a banner that had belonged to Charles M. Russell, he inhabited a different niche in the decades between the end of the First World War and start of the Second. “His contemporaries were artists like Ed Borein and Joe de Yong,” Rey says. “They kind of form a critical conduit in the history of art in the West, between the romantic painters of old and the more recent artists we venerate today. Their work didn’t appeal to the high-brow collectors who lived in penthouses in Manhattan, unless, of course, they spent summers at dude ranches in the West. The work of James and others spoke to common folk, especially young people coming of age.”

The Great Depression knocked America to its knees and James rose as a kind of icon ready-made for the working class. His mystique was not minted by pedigree.

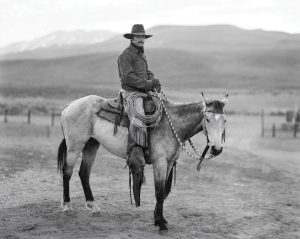

Will James and his wife, Alice, in the Washoe Valley, ca. 1923. Mountain West Digital Library, Digital Public Library of America. University of Nevada, Reno Libraries Digital Collections. UNRS-P2270-20

For Rey, James, as a character in his own right, evokes many allusions. He was like Iowan Marion Morrison undergoing a transformation of persona to become John Wayne. His journey can also be seen as a personification of Horace Greeley’s apocryphal commandment to go West and grow up with a country. Viewed in hindsight, he also became the inspiration for Ian Tyson’s famous crooning of James that “his heroes were his horses, and he drew them clear and true. On every page they’d come and jump straight out at you.”

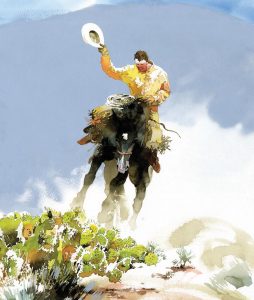

Bucking Horse 1 depicts the artist’s favorite subject: the cowboy way

of life. | The front and back cover of James’ book, Smoky

Contrary to the origin story James crafted in his best-selling 1930 autobiography, The Lone Cowboy: My Life Story, he, like Tyson, was a Canadian. Rather than being the son of a mother who died when he was an infant in Texas and then landing in Montana where he was raised by a trapper, James was born Joseph Ernest Nephtali Dufault in Saint-Nazaire-d’Acton, Quebec, Canada.

Believing he might have killed a man in an argument — he didn’t — James fled westward to the prairie, taking odd jobs and ranch work in Saskatchewan. He was a natural in the company of horses and in doodling to pass the time. Crossing the border into Montana, he took on a new name — William Roderick James — and a new destiny. The state left a deep impression. He set out for Nevada in 1914, where, not long after, he was convicted of cattle rustling and sentenced to prison.

Don Weller, Careful!

Watercolor | 18 x 15 inches

Behind bars, he made figure drawings using his photographic memory. In the years afterward, he served in the Army for a year at the end of World War I and got into the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco, falling under the tutelage of two part-time professors, Maynard Dixon and Harold von Schmidt. At every turn, James found people who liked him and opened doors.

Dixon told James to drop out of art school because he believed it would destroy the innate instincts that made him genuine. Von Schmidt encouraged him to submit an illustrated story to Sunset magazine. Soon, James was off again, now married, and the couple landed in Santa Fe. Working on a dude ranch outside of town, he was introduced to a well-connected guest from the East, who arranged for him to have a full-ride scholarship to Yale. Stir crazy, he struggled in the confines of academia and quit after a year.

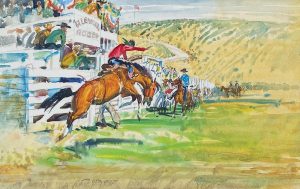

Robert Lougheed, Casey Tibbs

Watercolor | 8 x 13 inches

Through another fortuitous series of events, after his stories of cowboy life were published at Scribner’s magazine, his biggest break came when he was connected with Max Perkins, the famous literary editor in New York City who worked with F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Thomas Wolfe, and others. Perkins saw something raw and endearing in James. In 18 years, 24 of his books were published and 1,200 drawings. Five Hollywood films were inspired by his work. The book that made James famous was Smoky the Cowhorse, which won a Newbery Medal in 1927. It was reprinted at least 10 times and translated into a dozen different languages.

Decades ago, Rey began collecting James’ drawings and picked up a few paintings. He knew his father, Jim Rey, was familiar with him, but he was astounded and surprised to learn exactly how much. The elder Rey, born three years before James died, had grown up reading his Western books, and he admired his drawings. In many ways, Jim’s life paralleled that of James. He, too, spent his impressionable years on horses cowboying at ranches. He would go on to become a widely-regarded illustrator in San Francisco before pursuing Western art full time as a painter.

James Reynolds, New Kid

Oil | 18 x 24 inches

Jim, whose work is in his son’s show Cowboys North and South, told me that once, when he was a boy and tending to a sick horse whose treatment called for having it stand in the middle of a cool stream, he held a copy of one of James’ books and read it aloud. The horse seemed to like it. James had a knack for transporting readers. “To my dad and others, he was kind of like J.K. Rowling, but instead of transporting them into a fantasy world of witches at Hogwarts, he took them to a land where horses were their most trusted friends.”

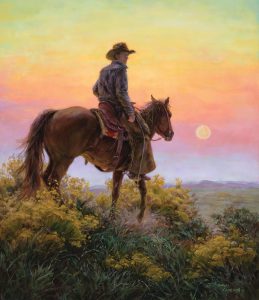

Shawn Cameron is among the featured artists during Cowboys North and South at Claggett/Rey. As if lifted from a Will James book, she writes this of the story behind one of her paintings that will appear in the show: “On Arizona’s northern plateau, our ranch mornings usually begin before sunrise. The western sky is often viewed as brilliant colors layered just above the horizon. I’ve often watched cowboys in the fall, garbed in worn leather chaps, riding through blooming chamisa oblivious to the predawn sky’s display of light and color. They are intent and purposeful, oblivious to the magic displayed. The show is brief for once the sun rises the multiple hues melt into a dusty blue/green that dominates the day.”

Jay Dusard, Martin Black

Archival Pigment Print | 38 x 48 inches

She says that the cowboy in her piece is her son, Brooks, who is focused on gathering and moving his cattle toward the corrals, as have three generations on this ranch before him. Poignantly, Cameron notes: “Will James was in our home growing up. He and I traveled many trails together after we became acquainted while reading Smoky the Cowhorse as a young child. I owned a small mustang horse of my own then named Coco, and instantly fell deeply in love with Smoky. In my mind, I knew and understood him well. Will was my companion on many days, and the pages of his books were usually open. He made the viewer feel they were part of the West and fully present in any scene he described or story he told.”

Shawn Cameron, Chamisa Moon

Oil | 20 x24 inches

As Cameron grew and matured into a professional artist, that became her goal as a painter — “to allow the viewer to relive the scenes I’d experienced, just as Will James did. I want those looking at my art to know what it’s like on horseback as the sun prepares to rise … searching the landscape for cattle and cowboys. Will James’ skill at bringing the reader into the story was a major motivation to me as a painter … and the reason I remain loyal to portraying the subject matter my family has lived for generations. I paint with much gratitude and respect to the man who revered that life as much as I do.”

Sculptor T.D. Kelsey, who is also in Cowboys North and South, still exudes a kindred fondness for James. “Of course, growing up in Montana, I was a big fan. He could draw a horse like no other person. He wasn’t the best painter, but he found a niche.” Kelsey wanted to emulate James’ characters. His mother, at one point, protested. “She said, ‘Will you please quit walking around like that bow-legged cowboy you’re reading about!’ He was one of my heroes, along with Charlie Russell. He was more approachable in my imagination because he was more of what I was. He rode horses and broncs and lived in Montana just like me. I could relate to him. Charlie Russell, on the other hand, may have been from Great Falls but he seemed unapproachable because he was so great and famous. I was scared to even think about him.”

T.D. Kelsey, No Place to Part Company

Bronze | 12 x 18 x 21.5 inches

Of any sculptor making loose representations of horses and cowboys, Kelsey is able to translate the same kind of electric energy in bronze that James conveyed in some of his drawings. There’s not only a feel for the form but empathy and compassion. In the Claggett/Rey show, Kelsey has submitted a piece titled No Place to Part Company, and it portrays a cowboy being whipsawed on the back of a rank horse. “The guy’s not bucked off yet, but he’s damned close to,” Kelsey says.

Jim Rey sees James as kind of a tragic character, “You know a special gift when you see it. The ability to communicate gesture is everything. Will James was able to achieve that. You saw it in his pencil drawings and then pen and ink and monochrome paintings and charcoal. You can see the progression. Unfortunately, he didn’t live long enough and wasn’t sober enough to really expand the talent he had.”

Will James, Bucking Horse 2

James was only 50 years old when he died of alcoholism in Hollywood, California, only months after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and brought America into World War II. It is known that many soldiers carried copies of James’ books with them to the battlefront, reminding them of what they considered home ground. In his latter years, James owned a ranch along Pryor Creek in the Pryor Mountains south of Billings and a home in Magic City. The largest collection of his work is at the Yellowstone Art Museum, and there’s a middle school named after him.

James remains a larger-than-life figure, and the Canadians, as Ian Tyson’s ballad demonstrates, proudly claim him as a native son. James is a figure who would otherwise qualify for the aphorism that sometimes colorful truth is better than fiction — or perhaps, it was the other way around all along. “Even though he flamed out, his was a life that mattered,” Bill Rey says.

Without pretension, James spoke to everyday real people. He knew his potential and his limitations. He wasn’t a pretender seeking praise from poseurs he didn’t respect. It’s not difficult to wonder, Rey suggests, if James, like a lot of people cast into the limelight, didn’t struggle with imposter syndrome. “I don’t think it’s a stretch to think that he, in some ways, wasn’t constantly looking over his shoulder worried that somehow the details of his past would catch up with him. It’s not hard to imagine that stress, which accompanied him being famous and yet needing to lie low, contributed to his heavy drinking,” Rey says.

If things didn’t happen exactly the way James wrote them down in his autobiography, it doesn’t matter, Rey says, “because the imagery he created was the way people wanted them to be.” The longing for an alternative, the metaphor of a cowboy or cowgirl riding the open range on the back of a trusty horse, is perhaps the strongest enduring archetype this country has.

“America needed Will James a century ago, and I like to think we need him now, someone to make us forget our differences and pull us into a common, shared adventure of escape, to be a distraction from all the bitterness floating around out there now,” Rey says. “There was a time when James’ novels and drawings spoke to us, no matter who we were. Today, they invite us to experience the kind of stories of the West our ancestors knew. There’s truth that can be found in the journey of seeking.”

Comprised of the visions of great sculptors, painters, and other creative people, the art appearing in his memory at the Claggett/Rey show may not be a precise composite of Will James, but it adds up to something greater. “Art transports us,” Rey says. “At the very least, conjuring up Will James’ spirit will be a lot of damned fun.”

No Comments