06 Sep A New Mexico Modernist

Occasionally, the phone rings, and it’s a call you’ll never forget. For artist Kim Douglas Wiggins, that call came one day in 1998. On the other end of the line was John Geraghty, a trustee of the Autry National Center for the American West, who had helped establish the organization’s Masters of the American West art exhibition and sale earlier that year.

Adormidera — California Before | Oil | 40 x 30 inches | 1998

“He said, ‘Doug, I wanted to do something new here with Masters of the American West,’” Wiggins recalls. Geraghty explained his desire to showcase artwork outside of Western Realism, a style canonized by the genre’s greats, from Russell and Remington to Catlin, Moran, and Couse. “‘I don’t know if it’s going to work,’” the artist recalls Geraghty saying, “‘but I’d like you and Kevin Red Star to come out next year, and let’s see what happens and what kind of results we get.’”

So, Wiggins set to work in his studio, creating a painting for the exhibition in the unmistakable style he had thoughtfully developed during his career: Modernist in inspiration, with exaggerated forms, dramatic light, symbolism, and high-key, vibrant colors that seemed to radiate from the canvas and illuminate the room. The resulting painting, Adormidera — California Before, depicts through symbolism the Hispanic influence on early California.

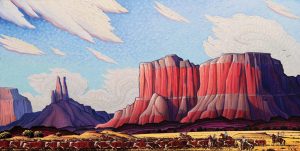

End of the Day | Oil | 24 x 48 inches | 2024

On opening night, Wiggins and Red Star walked through the museum’s gallery, looking for their work. “Finally, we see it,” Wiggins says. “And it’s all the way back, at the very back, by the back door, under the exit sign. So Kevin and I are standing there, and he looks over at me, points up at the exit sign, and says, ‘Do you think this means anything?’ And I said, ‘Lord, I sure hope not!’”

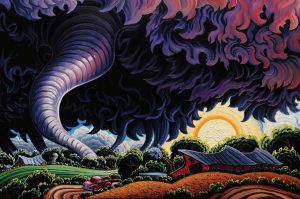

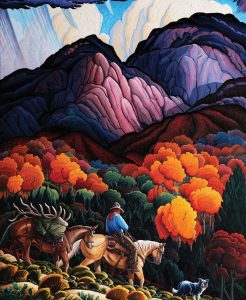

Along Tornado Alley | Oil | 24 x 36 inches | 2024

Wiggins had nothing to worry about. That evening, Adormidera — California Before was purchased by businessman Philip Anschutz, and today, it resides in the Crypto.com Arena (originally called the Staples Center) in Los Angeles, appearing behind such celebrities as Lady Gaga, Madonna, and Beyoncé during interviews for the Grammys.

The story demonstrates that being innovative takes courage, and any such initial growing pains that Wiggins and Red Star experienced early on helped open doors for a wide variety of representations to exist within Western art. “It’s been a climb, and it’s just normal and commonplace now,” says Wiggins. “But it’s not always been.”

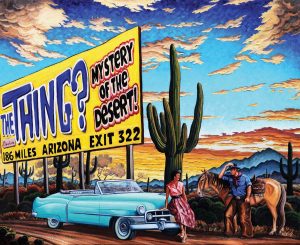

The Thing | Oil | 24 x 30 inches | 2024

Wiggins stands among the pioneering artists in the “Modern West” or “New Western Art” movement, alongside other greats including Red Star, T.C. Cannon, Earl Biss, Ed Mell, Howard Post, Donna Howell-Sickles, and Billy Schenck. The movement, which celebrates innovative artistic styles that explore traditional Western subjects, traces its beginnings back to the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in the 1960s. “It’s a reinterpretation that resonates with today’s audiences and reflects the complexities of modern life while paying homage to the region’s historical roots,” says Cyndi Hall, the general manager of Legacy Gallery and Manitou Galleries in Scottsdale, Arizona, and Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Manitou Galleries has represented Wiggins since the mid-1980s, and over those years, they’ve observed a growing appreciation and enthusiasm for his work. “Initially, some traditionalists were hesitant to embrace the bold and unconventional style of the New West. But over time, Wiggins’ ability to capture the spirit and vitality of the West in a contemporary manner has won over a diverse audience,” Hall says. “As ‘New Western Art’ has gained broader acceptance, the response to his work has evolved from curiosity and intrigue to admiration and acclaim. Collectors and art enthusiasts now eagerly anticipate his exhibitions, recognizing the depth and innovation in his pieces.”

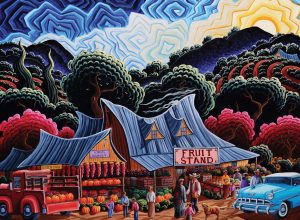

Fall in Rio Arriba | Oil | 36 x 48 inches | 2024

Staying true to his point of view despite any challenges was important to Wiggins because he believes that Western art represents the American identity in a way few other artistic genres can.

“The identifying factor of America is going to be the West,” he says. “And if you look at any ancient society in the world, whether it’s Greek or Egyptian or Chinese or Roman, you recognize the society through their artwork. … And I believe America, one day down the road, will be identified by the West. So it’s not that I just paint the West — the West is the identifying factor of American art.

“I’m trying to pull in elements into my work that portray the West through new words,” Wiggins continues. “I don’t believe we’re going to reach the next generation saying the same thing, the same way that we’ve always said it. And so, I tend to focus on Modernism. There are other artists who focus on Western Realism. They reach one section of people; I reach another section of people. Neither way is better than the other. It’s just important that we reach out and try to expand those horizons.”

Land of Buck Dunton | Oil | 60 x 48 inches | 2023

Given Wiggins’ recognizable style, some collectors might be surprised to discover that he began his painting career as an Impressionist. In 1983, at age 24, he was admitted as the youngest member of the Society of American Impressionists. But during his first show with the organization in St. Louis, when his work appeared alongside 30 preeminent artists including George Carlson, Sandy Scott, and Everett Raymond Kinstler, he mistook another artist’s painting of New Mexico’s Hondo Valley for his own. “It totally devastated me,” Wiggins says. “I had people who loved what I was doing as an Impressionist, but I left the show knowing that I had no real identity of my own. My work looked just like everyone else. And so that’s what changed my life right there.”

After that show, Wiggins began experimenting to develop a style that was distinctly his own, one that would be recognizable across any room. He explored Expressionism, Magical Realism, and symbolism, incorporating themes from each. He pulled ideas from things that had touched his life, including Native American design and Hispanic folk art. He studied the artwork of great painters. He was encouraged by his mentors, Henriette Wyeth and Alexandre Hogue. And the New Mexico landscape, a place with deep meaning for the artist, always provided generous inspiration.

The Spiritualist | Oil | 40 x 38 inches | 2024

During this time, Wiggins also joined an etching group led by Eli Levin. While working in the medium, he recognized that he could translate its cross-hatching and sweeping lines into his brushwork when painting. “I fell in love with etching,” says Wiggins. “This very stylized work that you see today really was developed through the etching process with lines that sort of parallel each other and the beautiful design work that really focuses on the composition.”

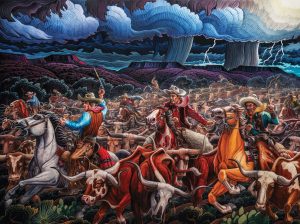

Artist Kim Douglas Wiggins works on The Chisolm Trail in his Rosewell, New Mexico, studio, which will appear in his November 2024 solo exhibition at Legacy Gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona.

This November, Wiggins will reveal new work during a solo exhibition, The Unexpected West, at Legacy Gallery in Scottsdale, including one of his largest paintings in 12 years, The Chisholm Trail, measuring 72 by 96 inches. The show takes place November 9 through 17, and artwork will be for sale by auction and draw.

“The exhibition showcases a variety of artistic expressions that Wiggins has experimented with throughout his career, from Impressionism to Modernism,” says Hall. “Attendees will be transported through different phases of his artistic journey, witnessing firsthand the evolution of his unique style.”

The Chisolm Trail | Oil | 72 x 96 inches | 2023

In a world that tends to lean on tradition, Wiggins stands out for his commitment to innovation. As a result, he has not only redefined how we see the West but also how we experience it, bringing a sense of wonder and beauty to those who encounter his work.

“I’m a storyteller, and I’m telling a story of the West, and I’m telling a story with new words, and with new life, and with new passion,” says Wiggins. “And hopefully, it has that same passion and free spirit and determination that the West is known for.”

No Comments