05 Mar PERSPECTIVE: BREAKING THE MOLD

Among the vast collection of artwork and personal papers that artist Eugenie Frederica Shonnard bequeathed to the Museum of New Mexico system following her death in 1978 is a pair of ceramic candlesticks she created in the form of little squirrels. In old photographs, the candlesticks sit on the artist’s coffee table. During her lifetime, Shonnard was internationally acclaimed as a sculptor, best known for her busts of Pueblo people and for working in a range of materials. But the squirrels tell another important part of her story.

Untitled (Three Birds) | Keenstone | 15.125 x 7.375 x 4.875 inches | Mid-20th Century | Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. | Gift of Eugenie F. Shonnard Estate, 1978 (2008.1.158). ©Museum of New Mexico Foundation. Photo by Brad Trone

Shonnard approached every creative act, from candlesticks to fine art sculpture, with the same level of commitment and a desire to honor human dignity and the beauty of the natural world. “She had a very democratic approach to art. She thought that what art needs to do is be part of everyday life,” says Christian Waguespack, Head of Curatorial Affairs and Curator of 20th Century Art for the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe. “For Shonnard, the design on a pillow can have just as much of an impact on a person’s life as a painting. That sets her apart.”

It was one of many things that set her apart. As an early 20th-century artist with an adventurous, determined spirit, Shonnard walked confidently through doors of opportunity that serendipity and her talent opened for her. Over and over throughout her long life, she succeeded at doing what many, including her family, thought she shouldn’t even try — and not only because she was a woman. She also dealt with and overcame serious health challenges that, for some, would have sidelined an artistic career before it began.

Laura Gilpin, [Eugenie Shonnard] | Gelatin Silver Print | 9.25 x 5.625 inches | 1940 | Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, Bequest of the Artist, P1979.130.1216, © 1979 Amon Carter Museum of American Art

An exhibition featuring the breadth and depth of Shonnard’s artistic output opened in March 2025 at the New Mexico Museum of Art. On exhibit through August 24, Eugenie Shonnard: Breaking the Mold represents the first major retrospective of her work since the mid-1950s. The exhibition and accompanying catalogue are aimed at returning attention to an artist of remarkable talent whose name faded in public memory after her death, largely because, Waguespack believes, she never took on students and had no descendants to promote continued awareness of her art.

Untitled (Squirrel Candleholders) | Glazed Ceramic | 8.875 x 3.25 x 2.75 inches | Date Unknown | Collection of the New Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art, Gift of Eugenie F. Shonnard Estate, 1978 (2008.1.81ab). ©Museum of New Mexico Foundation. Photo by Brad Trone

With no heirs, Shonnard donated her entire estate to the Museum of New Mexico, which oversees a collection of museums, historic sites, and archaeological services governed by the state. The New Mexico History Museum received all her papers, including letters, diaries, scrapbooks, family histories, and photographs. The New Mexico Museum of Art was the beneficiary of all her drawings, paintings, sculptures, tools, and personal art collection. And the historic Santa Fe home where Shonnard spent the last 50-plus years of her life became the offices of the Museum of New Mexico Foundation. Having so much of an artist’s experience represented in one place has allowed for in-depth scholarship and the creation of an exhibition that reflects her full and exceptional life and career.

Born in 1886 in Yonkers, New York, Shonnard was sickly as a child and often bedridden, suffering from an illness that doctors were unable to diagnose. Her family followed a Christian sect influenced by Emanuel Swedenborg [1688–1772], who saw God as infinitely loving and nature as central to life. From her earliest years, Eugenie was drawn to animals and the natural world. She later described her harmonious relationship with nature as fundamental to both her healing and art.

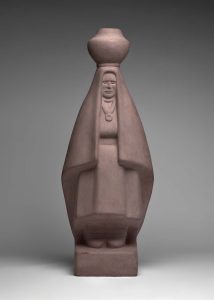

Untitled (Native American Woman) | Molded Plaster with Slip | 47.5 x 18.5 x 12 inches | 1954 | Collection of the New Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Gift of Eugenie F. Shonnard Estate, 1978 (2008.1.119). ©Museum of New Mexico Foundation. Photo by Brad Trone

A story she sometimes told was that, at one point, her parents believed their young daughter would not live long. A wise doctor suggested they remove all medications and bring some ducklings into her room, which gave her the spark to live. In other tellings, it was simply being in the garden with sweet little animals that helped her heal. Animals became a focus of her sculptural art — not all animals, but gentle, peaceful creatures — with the exception of one gorilla, which we’ll get to later.

In the early 1900s, there were few opportunities for women to study fine art. In part, this reflected the male opinion that it was inappropriate for women to see nude models used for sketching or sculpting the human figure. Instead, women were channeled into decorative design at places like the New York School of Applied Design for Women, which Shonnard attended from 1905 to 1907. Although the curriculum was limited, she “took it and ran with it,” Waguespack says.

Untitled (Duck Vase) | Ceramic | 5.875 x 3 x 7.5 inches | Date Unknown | Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Gift of Eugenie F. Shonnard Estate, 1978 (2008.1.83). ©Museum of New Mexico Foundation. Photo by Blair Clark

Fortuitously, the Czech artist and illustrator Alphonse Mucha was an instructor at the school then. Calling Shonnard “his best student ever,” Mucha became her lifelong friend. Later, he hired Shonnard as an assistant in his Prague studio, where she painted background figures in The Slav Epic, Mucha’s masterpiece depicting the history of Slavic people. Yet, Waguespack notes that even with background figures, “Each one she painted has a presence and personality, and shows that the history is built on everyday Slavic people, not just heroic figures. It informed the way she saw and who she wanted to glorify in her work.”

Likewise, Shonnard absorbed Mucha’s deep belief that the lines between design and fine art could and should be blurred. Mucha was best-known as a leader in the Art Nouveau movement, particularly for his stylized theatrical posters of the Parisian actress Sarah Bernhardt, which incorporated elaborate decorative elements drawn from nature. He passed on to his young student a passion for producing art to be enjoyed by all economic classes.

Mucha was also extremely influential in Shonnard’s life by encouraging her to travel to Europe and by sending his friend Auguste Rodin, the world-renowned French sculptor, a letter of introduction. Shonnard and her mother sailed to Paris for the first time in 1911. Rodin declined to accept her as a student before meeting her, but after seeing a bust she sculpted, he began offering critiques of her work and became a valuable mentor. From the French artist as well, Shonnard picked up the idea that even architecture can be fine art.

When the First World War broke out in 1914, Shonnard and her mother returned to New York, where she studied under sculptor James Earle Fraser at the Art Students League. A photograph from the time depicts a mixed-gender class, reflecting Fraser’s openness to teaching women fine art. While in the city, several important galleries and museums invited Shonnard to take part in exhibitions.

Chief Ohiyesa Communing with the Great Spirit | Mahogany | 37.5 x 16.375 x 25.375 inches | Circa 1920 | Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Gift of Eugenie F. Shonnard Estate, 1978 (2008.1.213). ©Museum of New Mexico Foundation. Photo by Brad Trone

Also in New York, she met the director of the Bronx Zoo, who commissioned her to sculpt a bust of Dinah, famous as the only gorilla in captivity at the time. Shonnard found herself alone in a room with Dinah, whom she hadn’t met before. Despite her fear, she was determined to produce an excellent likeness of the uncooperative ape. She soon discovered that as long as she was singing or humming, Dinah seemed calm and comfortable, so as the sculptor worked, she spent the entire time humming or singing. The bust is still at the Bronx Zoo. “It’s another great testament to what a powerful woman she was,” Waguespack says.

Following the war, Shonnard and her mother returned to Paris, where the artist exhibited her work in salons and received a major solo show at Galerie Allard. The pair traveled throughout Europe and spent summers in Brittany, where Shonnard carved busts of simple, everyday people from black marble. In 1927, archaeologist and anthropologist Edgar Lee Hewett invited her to move to Santa Fe. Hewett, the Museum of New Mexico’s first director, was aware of Shonnard’s exceptional renderings of Native Americans, a subject that had interested her since childhood. As he did with other prominent artists of the day, he offered her studio space at the museum and exhibited her work documenting Pueblo and other Indigenous cultures.

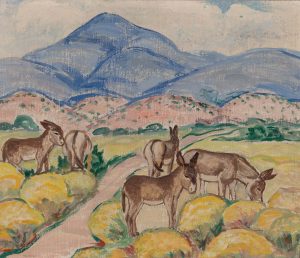

Unlike most early 20th-century artists, Shonnard’s sculptures of Native Americans were never generalized figures intended as stand-ins for all Indigenous people. “They had names. She depicted them as proud individuals,” Waguespack points out. Over the years, she spent considerable time at New Mexico’s pueblos, becoming close to the famed San Ildefonso Pueblo potter Maria Martinez, who taught her to make pottery. It was one of many mediums in which Shonnard worked. She painted in watercolor and oils, wove textiles, designed and carved furniture, and created bas-relief architectural elements. Among the latter were commissions for chapels, including one designed by the acclaimed New Mexico architect John Gaw Meem.

Outside of Santa Fe off the Taos Highway | Oil on Canvas | 14.25 x 17.25 inches | Mid-20th Century | Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Gift of Eugenie F. Shonnard Estate, 1978 (2008.1.29). ©Museum of New Mexico Foundation. Photo by Brad Trone

Shonnard was equally versatile with sculpture, working in clay, terracotta, sandstone, hardwoods, bronze, plaster, and selecting materials to match the feeling of specific pieces. She relished experimenting and invented her own carving medium, Keenstone, a cement-like compound she used to create both sculpture and architectural details. The lightweight material allowed her to continue working alone even into old age.

Shonnard was married from 1933 until her husband Edward Gordon Ludlam’s death in 1955. Yet while Ludlam was supportive of her career, converting an old barn on their property into a studio and serving as a shop hand for her woodworking, he remained in the background of her public life. Waguespack notes that, unlike many women artists of her day, she was never known as “the wife of…” This spirit of independence, combined with a “very strong interest in peace and harmony,” stands out alongside Shonnard’s artistic talent, he says. In fact, Waguespack adds, her motto seemed to be: “You say no, but I’m going to do it anyway.”

Gussie Fauntleroy has written for national and regional magazines, newspapers, museums, and galleries, has served as a book and magazine editor, and is the author of four books on visual artists; gussiefauntleroy.com.

No Comments