30 Apr PERSPECTIVE: ALLAN HOUSER [1914–1994]: A LEGACY OF INDEPENDENCE AND INNOVATION

At 20 years old, Allan Houser, who had grown up on his parents’ farm near Apache, Oklahoma, noticed a poster at the Indian Affairs Office in nearby Anadarko. It invited artwork submissions to recruit students into a new art program at the Santa Fe Indian School in New Mexico. The year was 1934, and the young man from the Warm Springs band of Chiricahua Apache had sketched on school paper throughout his boyhood and carved small bison from his mother’s soap bars. Without telling anyone, he sent some sketches to the address on the poster. A few weeks later, he learned he was accepted.

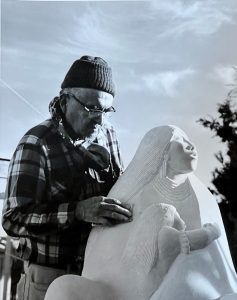

Allan Houser at work on Earth Mother in his Santa Fe studio in 1981. The figure was carved from Indiana limestone, and the artist often revisited the theme of mother and child in his work. Houser earned a National Medal of the Arts in 1992. Photo ©Glenn Green Galleries

Although his parents had hoped their son would take over the farm, Houser traveled to Santa Fe and entered the program known as The Art Studio. He gained drawing and painting skills there, revealing and honing his inherent talent. Just as significantly, however, he found himself rebelling against the strictly proscribed painting style imposed by the program’s founder and teacher, a non-Native artist named Dorothy Dunn. With students of various tribes, Dunn wanted every painting to adhere to a flat, two-dimensional style reminiscent of late 19th-century Plains ledger art. She believed this look would present as “Indian” when selling paintings to white tourists.

“She wanted a style that was marketable, but Allan didn’t want his creative output to be controlled,” says Houser’s son Bob Haozous, a contemporary artist and president of Allan Houser Inc. in Santa Fe. (Allan changed his name from Haozous to Houser as a young man, following the example of his brother, who believed they should be contemporary Americans. Two of Allan’s sons, Bob and Philip, returned to the original family name.)

Migration | Bronze | 63 x 37 x 32 inches | Edition of 10 | Courtesy of Allan Houser Gallery

Tony Chavarria, curator of ethnology at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe and a member of Santa Clara Pueblo, points out that even Houser’s early paintings produced in Dunn’s classes had a sculptural feel. “He could do the flattened perspective, but you can see he was very adept at understanding form, and how he would later translate that into three dimensions,” Chavarria says.

By rejecting Dunn’s idea of how his art should look, Houser opened the door to a lifetime of drawing, painting, and sculpture that honored the Chiricahua Apache and other tribes, as well as the human values of all people. At the time of his death in 1994 at age 80, he had become one of the most well-known and beloved Native American artists of the 20th century, with work in the permanent collections of the National Museum of the American Indian in New York City and Washington, D.C., the Smithsonian Museum of American Art in Washington, D.C., and the Oklahoma State Capitol Building in Oklahoma City, among other institutions and museums across the country and around the world.

The themes that run through Houser’s art emerged primarily from stories his father told of the hardships the family and tribe had suffered, and also their enduring strength and dignity.

The oldest son of Sam and Blossom Haozous, Allan — born in 1914 — was the first Chiricahua Apache born into freedom since colonialism had come to North America and altered their way of life forever; his parents and other tribal members had been held as prisoners of war for 27 years by the United States Army. His father, Sam, was a teenager when he was taken prisoner while traveling with Apache warriors, supplying ammunition and serving as a translator for the Bedonkohe Apache medicine man and warrior Geronimo, of whom he was a descendant.

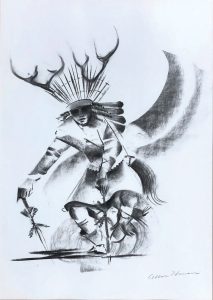

Pueblo Deer Dancer | Charcoal on Paper | 30 x 20 inches | c. 1984 | Photo ©Glenn Green Galleries

The U.S. government took the prisoners to army forts in Florida and then Alabama, where many died of illnesses born of the unfamiliar climate. The survivors were eventually transported to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. At their release, some settled in New Mexico, and others remained in Oklahoma, where they were allotted land for farming.

Sam and his family farmed but also held onto their tribe’s traditional songs and dances. Houser grew up absorbing these, along with his father’s memories.

“This was not a romantic vision of the past; it was living memory,” Haozous says. “Allan was portraying what his father had seen. He lived it through his father’s eyes.”

This included the difficult times, as portrayed in a painting titled Ill-fated War Party’s Return of an Apache war party returning to camp carrying the body of a fellow warrior across a saddle. In the 2008 film “Unconquered: Allan Houser and the Legacy of One Apache Family,” by the Oklahoma History Center, the artist says, “I could never turn away from my history. The strength that I have is my pride in who I am.”

Water Carrier | Bronze | 89 x 32 x 14 inches | Edition Unknown | 1986 | Courtesy of Allan Houser Gallery

In 1939, Houser married Anna Marie Gallegos in Santa Fe, and during World War II, he took his family to Los Angeles to work in the shipyards. Houser painted and sculpted at night and, through friends at the ArtCenter College of Design in Los Angeles, was exposed to Modernist sculpture by such artists as Henry Moore, Auguste Rodin, and Constantin Brâncuși. Later, he was also inspired by the work of British sculptor Barbara Hepworth and American artist Isamu Noguchi, particularly in how they incorporated negative space in a sculpture’s mass.

Following the war, Houser sent sketches to a competition to create a memorial honoring fallen Indigenous soldiers, which would be installed in Lawrence, Kansas, at the Haskell Institute boarding school, now Haskell Indian Nations University. His design won the commission. He had previously carved in wood, yet with no formal training in stone, he sculpted the striking, 8-foot-tall Carrara marble Comrade in Mourning, which continues to stand at the school.

Over the years, Houser became known as a skilled and inspiring teacher, beginning in 1950 at the newly opened Intermountain Indian School, a boarding school primarily for Navajo students in Brigham City, Utah. Twelve years later, when the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) was established in Santa Fe, he was asked to lead the sculpture department and taught there until 1975. The experience allowed Houser not only to meet students from around North America and learn about their tribal cultures but also to explore a range of mediums and sculptural methods, including cast bronze and fabricated sheet bronze and steel. Likewise, he encouraged his students to experiment and develop their own distinctive styles.

My Children | Bronze | 30 x 32 x 30 inches | Edition of 8 | 1982 | Photo ©Glenn Green Galleries

Just as importantly, Haozous points out that in an era when market influences were increasingly defining Native people and their art from the outside, and thus impacting their self-perception, Houser “wanted to give people a sense of self, so they could be better humans.” Among his many students and apprentices who later became well-known sculptors are Craig Dan Goseyun (Apache), Estella Loretto (Jemez Pueblo), and Cliff Fragua (Jemez Pueblo), whose statue of Po’pay, the leader of the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, was commissioned for the National Statuary Hall in Washington, D.C.

While Houser created his own art all along, his most prolific period began after he retired from teaching. “He was able to focus on what he wanted to do. It’s inspiring to know your best can come later in life, with that depth of experience and ideas that have been percolating for decades,” Chavarria says.

In the late 1970s, the artist’s son Philip purchased property south of Santa Fe, where Houser’s home, drawing/painting and sculpture studios, and the Allan Houser Sculpture Gardens and Gallery were built. Allan Houser Inc. was established in 1982 to preserve his legacy. The Sculpture Gardens and Gallery, open by appointment, features about 70 large-scale works in stone, bronze, and steel, as well as smaller sculptures, paintings, and drawings in the gallery.

Memories Live On | Bronze | 20 x 21 x 2 inches | Courtesy of Blue Rain Gallery

Houser’s later years were spent constantly sketching, painting, and sculpting, exhibiting widely, and earning numerous awards and honors, including becoming the first Native American artist to receive the National Medal of Arts.

In all his work, drawing was central. “Unconquered” quotes him explaining that all his sculpture began “through sketching, before working up my ideas in clay, wax, or plaster. … What makes art exciting, I believe, is the ability to experiment.” Among the imagery recurring throughout his career are Apache dancers, warriors, families, and figures offering prayer or a peace pipe. He also returned to the universal theme of mother and child many times.

Pueblo War Dance | Bronze, Lifetime Casting | 13.5 x 6.75 x 7.25 inches | Courtesy of Blue Rain Gallery

For Haozous, his father’s artistic output was born from a place that was neither the Western concept of fine art nor was it “traditional.” Instead, he sees it as reflecting Native people’s inherent creative adeptness with their hands and eyes, incorporating beauty and spiritual meaning into virtually everything. “We just go in the studio and ask ourselves who we are,” he says, recalling that his father always wanted to be in the studio right up until the final two weeks of his life. Yet, as serious as Houser was about art, he balanced hard work with humor — his son remembers him always joking and laughing — and with humility. “He told his sons: You’re as good as anybody in the world, but you’re not better,” Haozous says. “He loved all people, especially Native people. He had friends of all races.”

Chavarria adds that “From a Native perspective, it’s less about Allan’s renown, but what people remember is his spirit, and they remember it with fondness.”

Quoted in the film, Houser expressed his fundamental intention this way: “Human dignity is very important to me. I feel that way toward all people, not just Indians. In my work, this is what I strive for: this dignity, this goodness that is in man. I hope I am getting it across. If I am, then I am doing what I have always wanted.”

Gussie Fauntleroy has written for national and regional magazines, newspapers, museums, and galleries, has served as a book and magazine editor, and is the author of four books on visual artists; gussiefauntleroy.com.

No Comments