04 Jul In the Studio: Paint and Pu’ha

For Comanche artist Nocona Burgess, the studio is not only a creative workspace but also a container of memory, identity, tradition, and community. “It’s full of stuff,” Burgess says. “Just kind of off-the-wall stuff that I’ve collected. It’s art and objects from friends and former students. Some of my son’s stuff, my grandfather’s art, my dad’s paintings. And lots of books, because I’m always reading and researching historical imagery. They create a context for me. An immersion. And that’s what everything’s kind of built for in the studio. In Comanche, we say Nanisuwukaitu — sort of, ‘the spirit of the place.’ And here, its purpose is to send pu’ha, which is power or medicine, to that easel and that canvas. So, all this stuff, the books, the computer, the copier, the tools, the materials, are directly for that end result.”

Burgess stands at his easel, applying detail to a portrait in progress.

Burgess’ studio is in his family’s home in Santa Fe. “When we built this bigger house, it seemed kind of pointless to have a separate studio,” he explains. “I have artist friends who say there’s no way they could work at home. They’d just be watching TV and eating snacks all day. But I love working at home.”

The artist says he has plenty of workspace for creating his portraits of Native American people, often based on historical photographs, in his signature style full of color and emotional resonance. “I’m painting big 84-by-72-inch pieces in here, and there’s plenty of room,” Burgess says. “If I do need a bigger space, I just move into the garage. If I’m doing stuff like gesso or varnish, I can back the cars out, put down a drop cloth, and do all the messy stuff out there. If I need to use tools or build canvases, I can go in there and do it. And if it stinks from varnish or whatever, I can just close this door and let it dry while I continue to work.”

Located in Santa Fe, the studio is orderly and a place of purpose. “I need that, because I can’t focus if it gets too cluttered,” Burgess says.

Burgess’ studio is both a creative space and an office. “My sculptor friend Kevin Box says, ‘For every creative action, there’s an equal and opposite administrative reaction.’ And that’s true. This morning, I got up at about 6:15 and came out to the studio; I’m answering emails, and filling out information, and dealing with requests from museums for permission to use my pieces, and getting a show ready. It’s all that stuff that you just have to do.”

The artist chooses to work while surrounded by art and artifacts that hold importance for him. “They create a context for me,” he says. “An immersion.”

The name Nocona roughly translates as “one who goes out and returns,” and that’s appropriate for his art business. Through the end of the year, his schedule includes shows at the Santa Fe Indian Market, August 16 and 17; Reno Tahoe International Art Show in Reno, Nevada, September 11 through 14; Visions of the West, September 26 through October 11, and Art Untamed: A Night of Contemporary Artists, October 18, at The Bryan Museum in Galveston, Texas; a meet and greet at The Marshall Gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona, November 13; and back to Santa Fe for the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts Winter Indian Market, November 29 and 30. Somehow, he’ll also fit in visits to the Mesa Collection galleries in Tokyo and Kobe, Japan; the Rainmaker Gallery in Bristol, England; and Four Winds Gallery in Sydney, Australia.

Burgess lines up a stencil he created.

That kind of peripatetic lifestyle was typical for his ancestors, who roamed the Comancheria, and Burgess was steeped in that tradition from an early age. “My parents were pretty young when they had me,” he says. “My dad was 18, my mom was 19. Just teenagers. They were both working, and my dad was going to school. So, they would bundle me onto my dad’s Honda motorcycle and drop me off at my mom’s parents.”

The artist continually expands his techniques. Lately, he has been creating these stencils, adding details by hand later.

Those visits with his grandfather were formative, and the artist recalls his grandfather speaking Comanche and his grandmother speaking Kiowa while they watched “Bonanza” and “Gunsmoke.” “He’s singing songs, and I’m learning how to dance. Just hanging out with them and hearing stories.” The artist recalls reading the Time-Life Books series called The Old West with his grandfather, reading stories about the great chiefs, the warriors, the gunfighters, the generals, and also Famous Artists Annual, a series of books showcasing contemporary art. “I’m seeing Jasper Johns, Josef Albers, Jackson Pollock in this world of flat-style Indian art in Oklahoma, and then I’m looking at this. And you’re never going to see this stuff in Oklahoma. Not as an Indian kid.

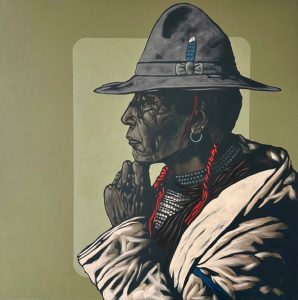

Burgess uses his architectural background to add visual depth to his canvases through horizon lines and color blocks. Many of his portraits are based on historical photos.

“So, that’s what got me into [art]: My grandfather, Simmons Parker, was a Code Talker in the D-Day Invasion of Normandy, and he was the grandson of [the Comanche Chief] Quanah Parker. My father, Dr. Ron Burgess, is the descendant of Chief Ten Bears. So those were my relatives and ancestors. That’s why this imagery is important to me. It’s not just in a history book. It’s in me. And in a way, all my subjects are Nu Numu Haa’Kana — my people.”

While art has always been a part of Burgess’ life, it took him a while to make it a career. He sold out his first show at age 5 as part of his father’s graduation show, but he turned to architecture in high school. He was at the University of Oklahoma on an architecture fellowship when he wondered, “What can I do to make a living and still create?”

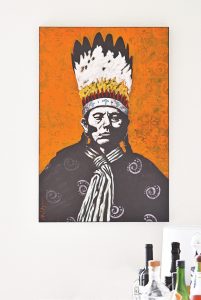

Hanging in Burgess’ studio, this portrait depicts the artist’s great-great-grandfather, Comanche Chief Quanah Parker.

“Art had always been kind of on the outskirts,” he says. “I knew of Native artists like Doc Tate Nevaquaya and Rance Hood and T.C. Cannon. And I emulated some of their work growing up. But it was never in my brain that art was something I was going to do. Then, when I came out to Santa Fe, it was like, wow! I saw guys like Tony Abeyta and Darren Vigil Gray who were just a shade older than me, and they’re doing it.”

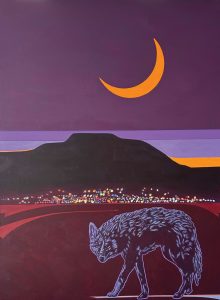

Nocona Burgess’ award-winning artwork honors Native American people for their struggle to sustain their traditions and identities.

Burgess also earned a Master’s in Art Education from the University of New Mexico, where he was fortunate to study painting with Nick Abdalla. “Nick was really impactful with me,” Burgess says. “He said, ‘You could do something with it, so I’m going to push you.’ And he did.”

After college, Burgess spent a year and a half in his studio just experimenting, learning his craft. Then, he did an entirely new series of paintings. “Suddenly,” he says, “the light came on. Somehow, it went from my brain to the canvas, and it became my style.”

Chief Peepechis/Cree | Acrylic on Canvas | 48 x 48 inches | Courtesy of The Marshall Gallery

“Then a buddy said, ‘Hey, man, I’m in this gallery off Canyon Road, and they’re looking for some painters.’ So, I took all the new paintings I had, like 10 of them. And they said, ‘Hey, we really like these.’ And then, all of a sudden, you’re selling one or two a month, and then they’re like, ‘Hey, we need more paintings.’ And it just went from there.”

Route 66 Coyote (Tucumcari) | Acrylic on Canvas | 48 x 36 inches | Courtesy of The Marshall Gallery

Today, Burgess’ work can also be found in the permanent collections of the Smithsonian Institute’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture in Santa Fe, and many others. His work is represented by Manitou Galleries in Santa Fe, New Mexico; The Marshall Gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona; Adobe Western Gallery in Fort Worth, Texas; Rainmaker Gallery in Bristol, England; Four Winds Gallery in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Sydney, Australia; and Mesa Collection Galleries in Tokyo and Kobe, Japan.

John Goekler is the author of Opening the Heart: The Life and Art of Gib Singleton and Moving Paint: The Life and Art of Earl Biss, as well as several award-winning texts and curriculum guides on global issues and sustainability. He lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

No Comments