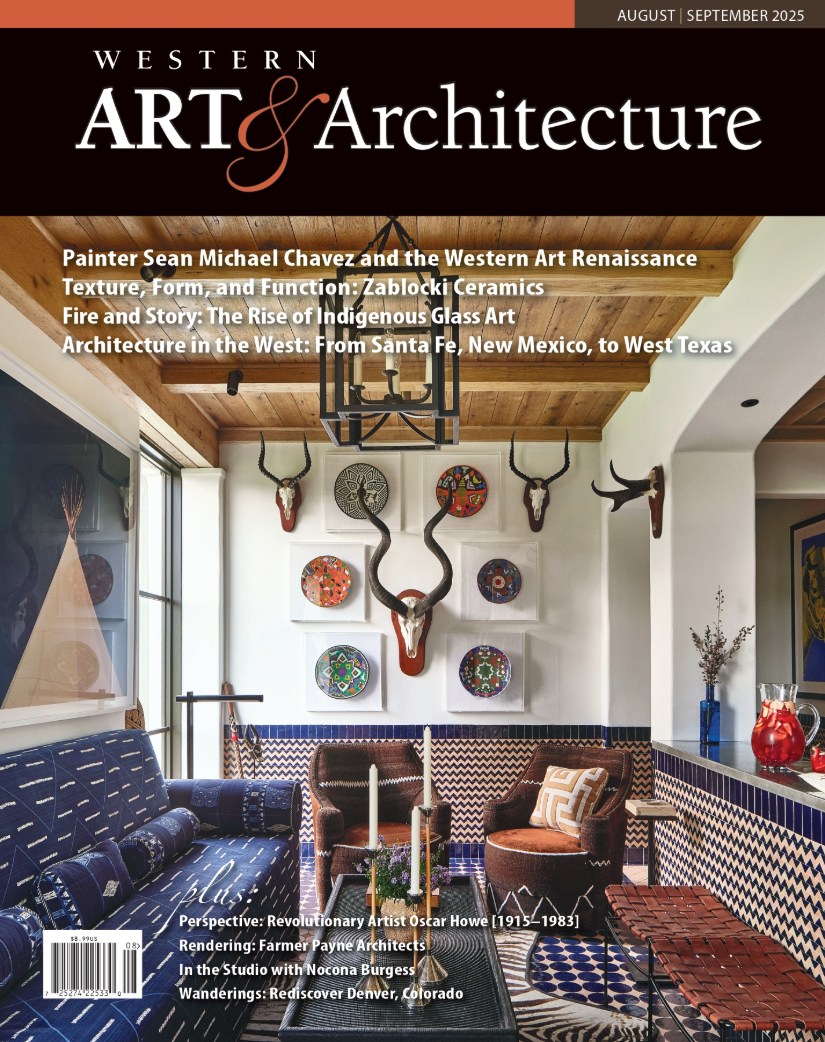

04 Jul Perspective: The Legacy of Revolutionary Artist Oscar Howe [1915–1983]

On the surface, Oscar Howe [1915–1983] was a thoughtful, quiet, patient man, dedicated to his work as an artist and teacher and to his people, the Yanktonai band of the Dakota tribe in South Dakota, where he grew up and spent most of his adult life. But beneath his gentle manner bubbled a powerful sense of indignation and anger at the patronizing attitude towards and unjust treatment of Native people by European Americans that he had witnessed all his life. When his outrage rose to the surface in 1958, it heralded a sea-change that has rippled in positive ways through generations of Native artists, as well as the broader art world.

Oscar Howe in his Studio at the W. H. Over | Museum | Photograph | ca. 1968 | 2319.1, Oscar Howe Papers, Archives and Special Collections, University Libraries, University of South Dakota

The tipping point came in the form of a rejection letter from the jurors in that year’s Indian Annual competition and exhibition at the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Howe had been juried into the show many times before and had previously been awarded best in show; he had also served as a judge in the compention, an honor that came with earning the top award. The artist was steeped in Dakota culture, having absorbed stories and knowledge from his grandmother, and he considered his creations to be true visual expressions of his people’s culture and artistic roots.

So, when the 1958 Indian Annual judges rejected the painting he entered because it was “not in the traditional Indian style,” Howe reached the end of his patience. He wrote a letter to the Philbrook, eloquently yet bluntly expressing the frustration he and many other Native artists of the time were feeling. It read, in part: “There is much more to Indian Art, than pretty, stylized pictures. There was also power and strength and individualism (emotional and intellectual insight) in the old Indian paintings. Every bit in my paintings is a true studied fact of Indian paintings. Are we to be held back forever with one phase of Indian painting…? We are to be herded like a bunch of sheep, with no right for individualism, dictated as the Indian has always been, put on reservations and treated like a child…. Well, I am not going to stand for it. Indian Art can compete with any Art in the world, but not as a suppressed Art….”

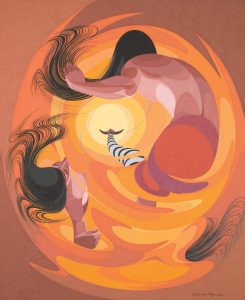

Sacro-Wi-Dance (Sun Dance) | Casein on Paper | 26 x 21 inches | 1967 | Courtesy of the Oscar Howe LLC

Howe’s mention of “pretty, stylized pictures” referred to a style that had been taught to Native artists, including himself, at New Mexico’s Santa Fe Indian School by non-Native art instructor Dorothy Dunn through The Studio School, an art program she founded and oversaw until 1937. Based on Pueblo pottery, Dunn taught a flat, two-dimensional style in watercolor, which she encouraged her students to employ when portraying ceremonies, dances, and other aspects of Native life. She and other proponents considered it to be a true “Indian style,” recognizable as such and thus marketable to tourists.

Howe’s letter upended that conception. Christina Burke, an independent curatorial consultant and formerly curator of Native American Art at the Philbrook, points out that Howe was accepted into and even juried into later Indian Annual shows, with no hard feelings on either side. However, the discussions that followed his letter led to significant changes in the exhibition’s rules and helped pave the way, well beyond the Philbrook, for countless other Native artists to explore their own distinctive forms of creative expression.

Origin of the Sioux | Casein on Paper | 28 x 19 inches | 1960 | Courtesy of the Oscar Howe LLC

Growing up on the Crow Creek Sioux Reservation in South Dakota, Howe was part of a Dakota-speaking world just a couple of generations removed from pre-reservation life, when many were struggling to get by. His family discouraged his inherent interest in art, hoping to direct him toward an easier life. Yet, even without access to paper or pencils, the young boy found ways to draw. “He would say [in recorded interviews] that he always liked the sensation of drawing, of mark-making, in dirt or ashes,” says Amy Fill, director of the University Art Galleries at the University of South Dakota (USD). Along with Burke and USD professor emeritus Carol Geu, Fill is part of a team compiling a catalogue raisonné of Howe’s lifetime body of work, projected to be published in late 2026.

Skin Painter | Casein on Paper | 15 x 22 inches | 1968 | Courtesy of the Oscar Howe LLC

At age 7, Howe was sent to Pierre Indian School, a boarding school in South Dakota. There, he eventually found encouragement for his interest in drawing after a rough start that included health problems and physical and psychological abuse. Sent home to recover, he spent two years with his maternal grandmother, Shell Face, who nursed him back to health and told him stories of their people and traditions. Her words helped reinforce the deep connection with his culture that would fuel his art.

Wood Gatherer | Casein on Paper | 23 x 17 inches | 1972 | Courtesy of the Oscar Howe LLC

After returning to Pierre and finishing high school, Howe worked for a time before enrolling in Dunn’s art program at the Santa Fe Indian School. There, his talent became clear, and he learned quickly — one of his traditional Dakota names was Ksapa, meaning “the intelligent one.” Although his painting at the time aligned with what Dunn taught, Burke points out that Howe’s early style also echoes historical Plains paintings on hide, cloth, and paper, which he saw as the true roots of his art.

An intensely creative artist, he soon began challenging himself to express Dakota stories and culture in an ever-evolving style, likely bored with Dunn’s formulaic direction, says Kathleen Ash-Milby (Navajo), curator of Native American Art at the Portland Art Museum in Oregon. Ash-Milby, formerly with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in New York City, served as the lead curator for that institution’s 2022 exhibition Dakota Modern: The Art of Oscar Howe, the artist’s first major retrospective in 40 years.

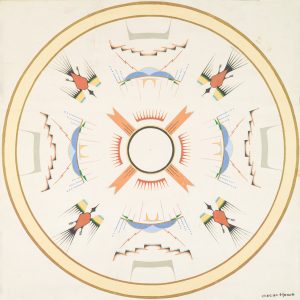

Sun and Rain Clouds Over Hills in the Dome of the Carnegie Library building in Mitchell | Drawing for Mural, Tempera on Watercolor Paper | 21 x 22 inches | 1940 | Courtesy of the Oscar Howe LLC

Between Santa Fe and the start of his 26-year teaching career at USD in 1957, Howe trained in mural painting with the Swedish artist Olle Nordmark in Oklahoma, painted murals in South Dakota, and, during World War II, spent three years in the Army in Europe, where he met his wife, Heidi. He earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts from Dakota Wesleyan and later a Master of Fine Arts from the University of Oklahoma. His paintings shifted from finely rendered pictorial imagery into greater abstraction while continuing to focus on Dakota subject matter.

Most critics assumed Howe’s later style was derivative of European Modernism, and Cubism in particular. However, Howe, who was well-educated in art history, repeatedly rejected that claim, explaining that his method drew on his ancestors’ use of color, line, and abstraction, as seen on such objects as the parfleche and in quillwork and beadwork on clothing and moccasins. He spoke of this as the traditional Tohokmu (spider web in Dakota), or “point-and-line,” by which he located points on the paper and connected them through intuition, reflection, and contemplation. Joseph Williams, a Wahpéthunwan Dakota artist and USD graduate — who, as a teen in the 1990s, participated in the Oscar Howe Summer Art Institute, which Howe established for young Native artists — recalls hearing that Howe “would often let his canvas sit for days as he searched for an image to emerge.”

Pipe Ceremony (Accanupapi) | Casein on Paper | 17 x 27 inches | 1972 | Courtesy of the Oscar Howe LLC

The artist began his career in watercolor and continued painting in water-based mediums, primarily gouache, tempera, and watercolor with a casein binding, all of which produce rich, more opaque colors. The Fabriano Italian watercolor paper he used suggested the feel and texture of rawhide, says Fill, who, with guest curator Delphine Red Shirt, developed The Oral History of Shell Face; Oral Traditions in the Work of Oscar Howe, on veiw on USD’s campus through June 30, 2026.“His use of color and shading is unmatched,” she says, adding that every time she views Howe’s work, she sees something more. “The first impression is the beautiful, bold abstract forms; then you’re seeing the figures emerge and the way he can contort the figures; and then all the incredible detail.”

During his lifetime, Howe was a hometown hero, popular in South Dakota and appearing frequently on local PBS programs. In 2022, the Smithsonian’s Dakota Modern retrospective was significant in bringing awareness of his work to the larger art world and recognizing his place in that world, Ash-Milby says. Fill elaborates on the merging of Modernism and tradition in his art: “His paintings are documents of culture, like a portal into his life and knowledge. But being in a non-contextualized, generally empty space allows them to feel in-the-moment and always seem fresh in the present and alive,” she says. “He’s saying, ‘It’s a living culture, not stuck in the past.’”

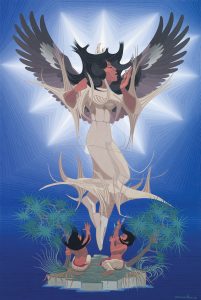

Eagle Dance | Casein on Paper | 26 x 19 inches | 1960 | Courtesy of the Oscar Howe LLC

Danyelle Means, executive director of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, is Yanktonai Dakota on her grandmother’s side and Oglala on her grandfather’s. Growing up in South Dakota, she remembers seeing Howe on television — a child’s measure of success — and feeling enormously inspired to believe she could also be successful. It was a time when her uncle, the prominent Oglala Lakota activist Russell Means, was among those passionately speaking up for Native rights, and Danyelle realized Howe’s was another important voice.

Health issues compelled the artist to pull back from painting when he was still relatively young, which meant the peak of his artistic career in the 1960s coincided with a period of creative momentum that included the founding of the highly influential Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. “People in the early 1960s were breaking free from constraints, and I think he was the catalyst for many of these changes,” Ash-Milby says. “He pulled the plug, and it all came flowing out.”

Gussie Fauntleroy has written for national and regional magazines, newspapers, museums, and galleries, has served as a book and magazine editor, and is the author of four books on visual artists; gussiefauntleroy.com.

No Comments