.jpg)

19 Oct Perspective: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Other Women

In his 2009 best-selling novel, The Women, acclaimed writer T.C. Boyle wrote about Frank Lloyd Wright’s relationships with his three wives and his mistress, Mamah Cheney. Several biographies of Wright have also covered this topic. But very little has been written about the story of Wright’s working relationships with some of his strong-willed, independent-minded female clients on the West Coast. These “other women” in Wright’s life were able to get him to make significant changes in the designs for their homes, something Wright refused to do for most of his clients. Two of these women had especially interesting experiences in working with Mr. Wright.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s first independent female client on the West Coast was oil heiress Aline Barnsdall, who commissioned him to design a home and arts complex in 1917. Barnsdall was an unusual woman in several ways. She had inherited a large fortune from her father, yet she was an outspoken supporter of the Russian Revolution from its beginning. She also had a close friendship with the famous American anarchist Emma Goldman. Aline chose never to marry, but gave birth to a daughter by a lover.

After living in Europe during her teens, Barnsdall moved to Chicago before World War I, where she met Wright about 1915. She asked him to design a new facility for an avant-garde theater in Chicago. But Aline soon changed her mind and asked Wright to design her own theater in Los Angeles, which had a thriving theater scene by the 1910s.

This commission would evolve into a much more complex project: Aline’s dream eventually grew to developing a facility that would include a performing arts theater, a motion-picture theater, apartments for actors, commercial shops, artists’ studios and a house for herself and her daughter. She chose Wright for the project because of his reputation as a progressive designer, and for his love of the arts.

In the end, however, only four of the proposed structures were actually built. Three remain standing and are now part of Barnsdall Art Park, which is owned by the City of Los Angeles and open to the public as a museum.

Early in 1919, Barnsdall bought a 36-acre tract, known as Olive Hill, perched above Hollywood Boulevard just west of Vermont Avenue. (The village of Hollywood had been incorporated into Los Angles in 1910.) The lot Barnsdall purchased was a problematic site for such a grandiose project. The top of Olive Hill was barren and dusty, and the nearby Hollywood Hills were mostly open grassland at that time. The site did provide unimpeded views of downtown Los Angeles to the south, the San Gabriel Mountains to the north and the Pacific Ocean to the west. However, it was far from the commercial center of Los Angeles and isolated from the settled parts of Hollywood. The site had very little to offer any serious developer unless they had a unique vision and an unrelenting passion for seeing a dream realized, as Barnsdall did.

Aline decided she wanted Wright to design her home first and place it atop Olive Hill. But this required significant design changes from Wright, who had been working under the assumption that the theater would be placed on the crown of the hill. After reworking his preliminary plans, construction finally began on Hollyhock House in 1919. The home’s nickname was derived from the stylized hollyhock motifs Wright designed for the concrete finials along the exterior of the house; hollyhocks were Aline’s favorite flower, and they grew in abundance on Olive Hill.

In 1920, Barnsdall asked Wright to design two guest-houses on Olive Hill. These were called Residence A and B, and were completed in 1921, the same year as the main house. By this time, Wright still had not completed a final set of working drawings for the sited theater. Despite this disappointment, Aline asked Wright to design a private schoolhouse on the hill for her daughter and other children. But before the foundation of the schoolhouse was completed, the City of Los Angeles halted construction for alleged code violations. (Wright never did finish the building; it was completed by Austrian-born architect Rudolph Schindler.) While Wright was still working on the schoolhouse, he had Residence B remodeled as his studio and went over the $30,000 budget Aline had set for it, further aggravating tensions between them. Residence B was demolished in 1948, but Residence A still stands.

Hollyhock House is a two-story, 6,000-square-foot residence, with seven bedrooms, seven baths, a large living room, formal dining room, a music room, library, conservatory and an enclosed sun porch. The main rooms are grouped around a garden court and there is another walled patio off the south end. A primary source of tension between Barnsdall and Wright were the frequent design changes Aline requested of Wright during construction. For example, she asked for a reflecting pool in front of the south entrance, a children’s wading pool with terraced seating at the eastern end and a row of kennels running off the north-east corner. In the end, she got each these features, all of which survive today just as Wright designed them.

The various tensions between Wright and Barnsdall eventually caused a break in their working relationship. She fired him from the project temporarily in 1921, and then rehired him to design the schoolhouse. After work on that structure was halted, she fired him again, and he threatened to sue her for unpaid bills relating to the construction of her house. These issues were eventually settled out of court and a few years later they renewed their friendship.

None of the other structures Barnsdall envisioned for Olive Hill were ever built, yet she got Wright to design a remarkable home for her. Jeffrey Herr, curator of Hollyhock House, described its importance: “Its use of indoor-outdoor spaces marks it as a prototype of the modern ranch house.”

Although Aline Barnsdall may not have achieved her ultimate dream of a center for performing arts, her vision did lead to the creation of one of America’s most innovative and influential houses.

Della Brooks Walker was a widow living in Carmel,

California, in 1945, when she bought an acre lot on a prominent rocky outcropping on Carmel Bay. On June 13 she wrote a letter to Frank Lloyd Wright, describing her site and asking if he would design a beachfront house for her. She expressed her vision for her future home in poetic terms: “I am a woman living alone — I wish protection from the wind and privacy from the road, and a house as enduring as the rocks, but as transparent and charming as the waves and as delicate as the sea shore. You are the only man who can do this. Will you help me?”

Della Walker’s great-grandson, Chuck Henderson, says that before she wrote this letter she told her family that she chose Wright as her architect after seeing photos of Fallingwater. “If he could do that for a stream,” he quotes her as saying, “just imagine what he could do with an ocean.”

Obviously, Mrs. Walker was a woman who knew exactly what she wanted, and knew how to express herself clearly and eloquently to get it. When Wright received Della’s letter, he responded promptly, saying he’d be happy to design her house. But a number of testy exchanges between Wright and

Walker during construction show that the process of designing and building her home was anything but seamless.

The Walker House is a single-story, five-room residence, with three bedrooms, a combination living room and dining room, and 1,200 square feet of living space. The walls are made of local Carmel stone and the house appears to be an extension of the rock outcropping upon which it sits, making it a classic example of Wright’s organic design principles. For Walker, Wright created a perfect blending of sea, sky, sand and stone, using local materials in a magnificent natural setting. The home was among Wright’s favorite designs of all his West Coast residences, one he affectionately referred to as “The Cabin on the Rocks” in his correspondence with Mrs. Walker.

But those letters were not always friendly after Della began insisting on certain changes in Wright’s design. Two of those changes prompted particularly caustic responses from Wright.

When construction was well underway, Mrs. Walker requested a change in the kitchen that caused a battle royal between herself and Wright. She wanted a door put in the north wall of the kitchen so she could put the trash can outside easily. When he got her request, Wright responded indignantly in a letter dated February 27, 1951. “Again we are up in the air. Looks very much as though the Cabin on the Rocks was on the rocks in more than one sense. … I was happy to build it, as I put my best mind and heart into producing a little masterpiece appropriate to the unique site. An ordinary ‘door and window’ house on the site would look as foolish as a hen where you ought to see a seagull. I am unwilling to spoil my charming seabird and substitute a hen. You don’t need me for that. Anyone can do it.”

Wright and Walker arrived at a compromise and he agreed to sink the trash can into a hole bored into the concrete deck so it couldn’t be seen by passersby. The architect still opposed the addition of a door in the kitchen wall, but since she was paying the contractors, in the end Wright agreed and Della got her door.

When construction was nearly complete, another conflict occurred when Walker hired renowned landscape architect Thomas Church to design a landscape scheme for her house. When Wright was informed of this, he fired off an irate letter to her, dated March 21, 1952. “One of my former apprentices says to Aaron Green ‘Someone has ruined Mr. Wright’s house with landscaping.’ And Walter Olds, distressed, said ‘Mrs. Walker hired a professional landscaper to undo all Mr. Wright has done for her.’ If you did employ one, it is the first time it has happened to me in a long lifetime of building. The first destructive insult. I don’t believe it. Throughout the nation, these destructive vermin plant a skirt of shrubbery around a house and stick up a couple of trees at the entrance. ‘A William Worse than Wurster’ might be benefitted by this stock performance. Not so the Cabin on the Rocks. Is it all true? … I hope what I hear is not true and loves labor lost.”

But Della stuck to her guns and her wishes prevailed again over the heated objections of Mr. Wright. Thomas Church’s landscape design was carried out largely as he planned, while Wright’s crew cooperated during the final phase of construction. Della Walker remarried in 1959 and lived happily in her home for 26 years until her death in 1978. Her descendants still own the house, and maintain it with all of its original features, just as Mr. Wright — and Mrs. Walker — designed it.

- Aline Barnsdall gave birth to a daughter, Louise Aline Barnsdall, known as “sugartop,” in August 1917, in Seattle. Though the speculation was that Polish actor and director, Richard Ordynski, was the child’s father, Barsndall listed author Roy George on the birth certificate.

- Despite having few windows, Hollyhock House combined equal amounts of interior and exterior living space connected by glass doors, a porch, pergola or colonnade. rooftop terraces increased the outdoor living space. Barnsdall’s favorite flower, the Hollyhock, was incorporated into the decorative program of the house and can be seen on the roofline, the walls, columns, planters and even furnishings.

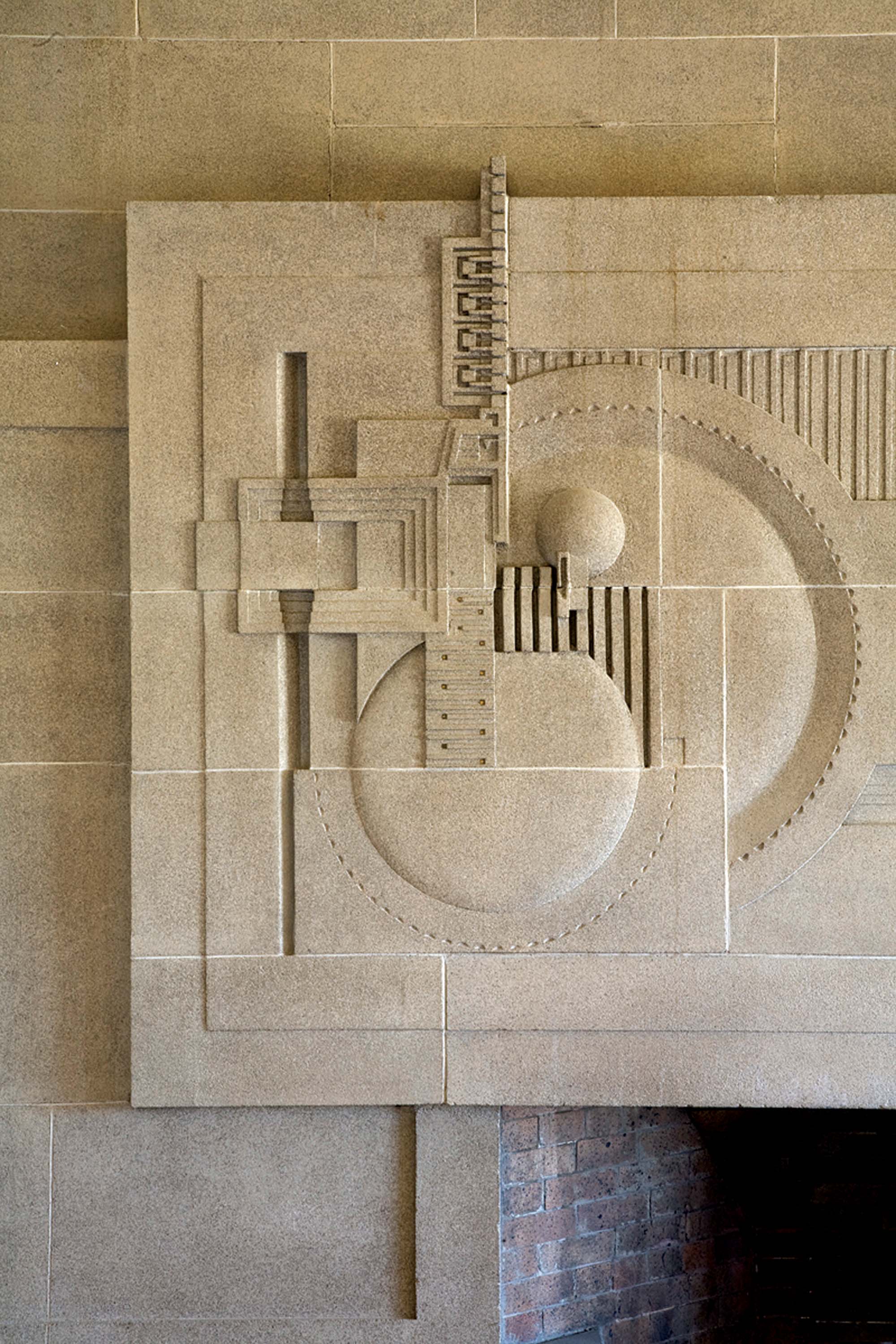

- Among the unique features of the home are leaded art glass, a grand fireplace with a large abstract bas-relief, seen here, and even a moat.

- Completed in 1952, the Cabin on the Rocks was built on Carmel Point in Carmel, California, with baked-enamel shingles of blue- green to blend with the sea and sky.

- Built on granite boulders with a triangular wedge foundation of Carmel stone, from a distance the home looks like a ship cutting through the waves of the Pacific.

- The largest room in the 1,200-square-foot home (including the car-port) is the hexagonal shaped living room with glass and built-in seating on three sides, and a floor-to ceiling fireplace on the fourth wall that is designed to burn logs leaning vertically against the wall.

- This image of Della Walker was taken in her Cabin on the rocks.

.jpg)

No Comments