09 Jun Perspective: Bill Owen [1942-2013]

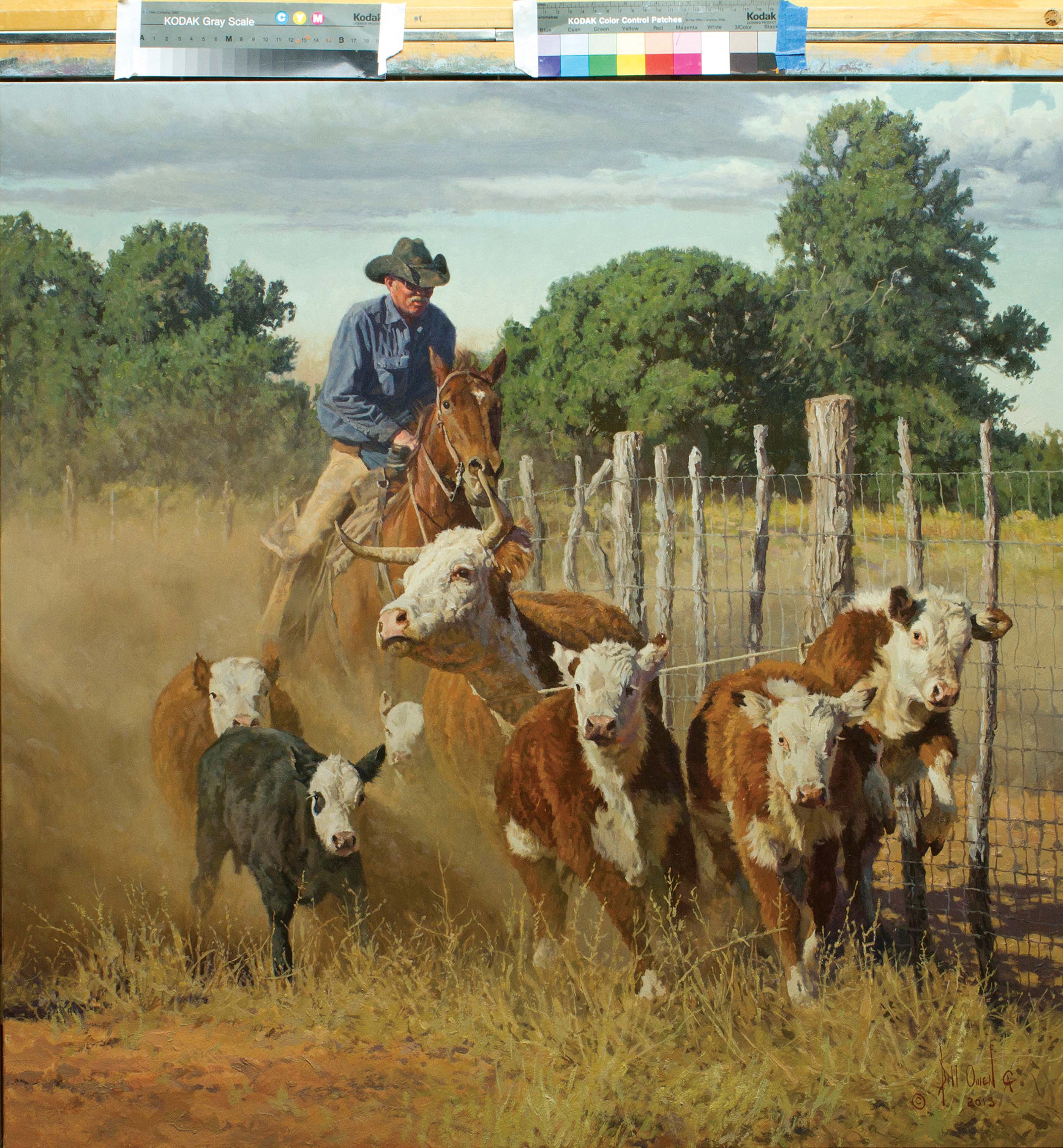

As dust flies, a weathered-looking cowboy leans in with concentration as he rides up behind a group of calves running alongside a fence. He has just roped a calf but now a cow has run into the taut rope, pulling the calf off its feet and threatening a pile-up. Chuck Schroeder, former director of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, chuckles as he thinks about the scene. “It’s the kind of mess that those of us who’ve cowboy’d — we’ve all been there and done that,” he says. “We know ‘Dadgummit!’ was coming out of that cowboy’s mouth.”

Caught a Little Deep was Bill Owen’s final painting before the artist’s sudden passing on June 15, 2013. The setting is the historic Babbitt Ranches in Arizona, one of a number of ranches where over his long career Owen spent time working cows, taking photographs and gathering material for his art.

The painting reflects the qualities that compel Owen’s peers in both the cowboy and art worlds to describe him as a “quintessential cowboy artist.” Or as Schroeder puts it, “It’s not too strong a statement to say that Bill Owen will go down as certainly one of, if not the, greatest cowboy artists in the American West. He simply had the capacity to tell the story of the American cowboy as he lived it and saw it, with honesty and with deep feeling for the land, livestock and people.”

Owen was not simply an artist who painted cowboys, nor was he a cowboy who knew how to paint. “He was a great artist who also happened to be a very competent cowboy,” Schroeder says. The two lifelong passions merged in works whose meticulous planning and execution infused every detail with accuracy — because, like Schroeder, Owen had “been there and done that.” At the same time his paintings communicate a deep understanding of color, composition, narrative action and light, developed over decades by a primarily self-taught artist who continuously pushed himself to improve. Caught a Little Deep also alludes to a characteristic Bill Owen personality trait: his sense of humor and inclination to look at life — both the challenging and lighter times — with clowning jokes and an infectious, ready smile.

Owen was a member of the Cowboy Artists of America (CA) for almost 40 years, serving three times as the organization’s president and on many committees and boards. Ironically, as a man who leaned on old-fashioned cowboy values, he was instrumental in the initial development of the organization’s website, relates acclaimed artist and current CA President Martin Grelle. “He saw where the future was going, probably before most of us did.”

Over the decades Owen earned more than 30 medals and awards at the Cowboy Artists of America Annual Sale & Exhibition, including the equivalent of Best of Show three times and the coveted CA Award five times. The latter was especially meaningful because it is conferred through a vote by active CA members for the best body of work, based on at least five pieces. Owen’s widely collected paintings have been exhibited in such institutions as the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and the Whitney Western Art Museum in Cody, Wyoming, as well as the Grand Palais in Paris, France, and in Beijing, China. During what would have been his 40th Cowboy Artists of America show, in October 2013, his final painting won the Buyer’s Choice Award, selected through secret ballot by all attending the show.

Born in 1942 in Gila Bend, Arizona, Bill Owen came to the cowboy life the way many do, as the son and nephew of men who worked with cattle. He grew up helping out on his uncle’s ranch, absorbing the Old West code of honesty, hard work, camaraderie and trust in a man’s word. His mother was a painter, and Owen’s artistic side began to emerge as a boy. Although he had no formal art education, his perfectionism, keen observation skills and ability to learn from other artists became the tools he honed throughout his life. Fellow cowboy artists Joe Beeler and Tom Ryan were especially influential in his development, notes his widow, Valerie Owen.

In the late 1960s Owen received his first gallery representation and began balancing cowboy life, the gathering of reference material, and studio time. He was invited by CA co-founder Beeler to apply for membership in 1973. Owen was 31. From then on, the organization and its members were an integral part of his life. Among his many contributions, Grelle points to Owen’s involvement in returning the annual exhibition to its original location at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in 2011, after 37 years at the Phoenix Art Museum. “He felt like the show was going home,” Grelle says.

For many who knew Owen, an event that took place in 1989 exemplifies both his artistic commitment and his character. While practicing team roping for a rodeo, a serious mishap led to the loss of sight in his right eye. Rather than allow the loss to end his painting career, he redoubled his efforts and soon learned to compensate. In the view of collectors and fellow artists, his paintings became even more exceptional than before. Even Owen’s ability to sculpt eventually returned. While painting in oil remained his primary means of artistic expression, he created cowboy-related watercolors, drawings in graphite and sculpture in bronze, winning awards in all mediums.

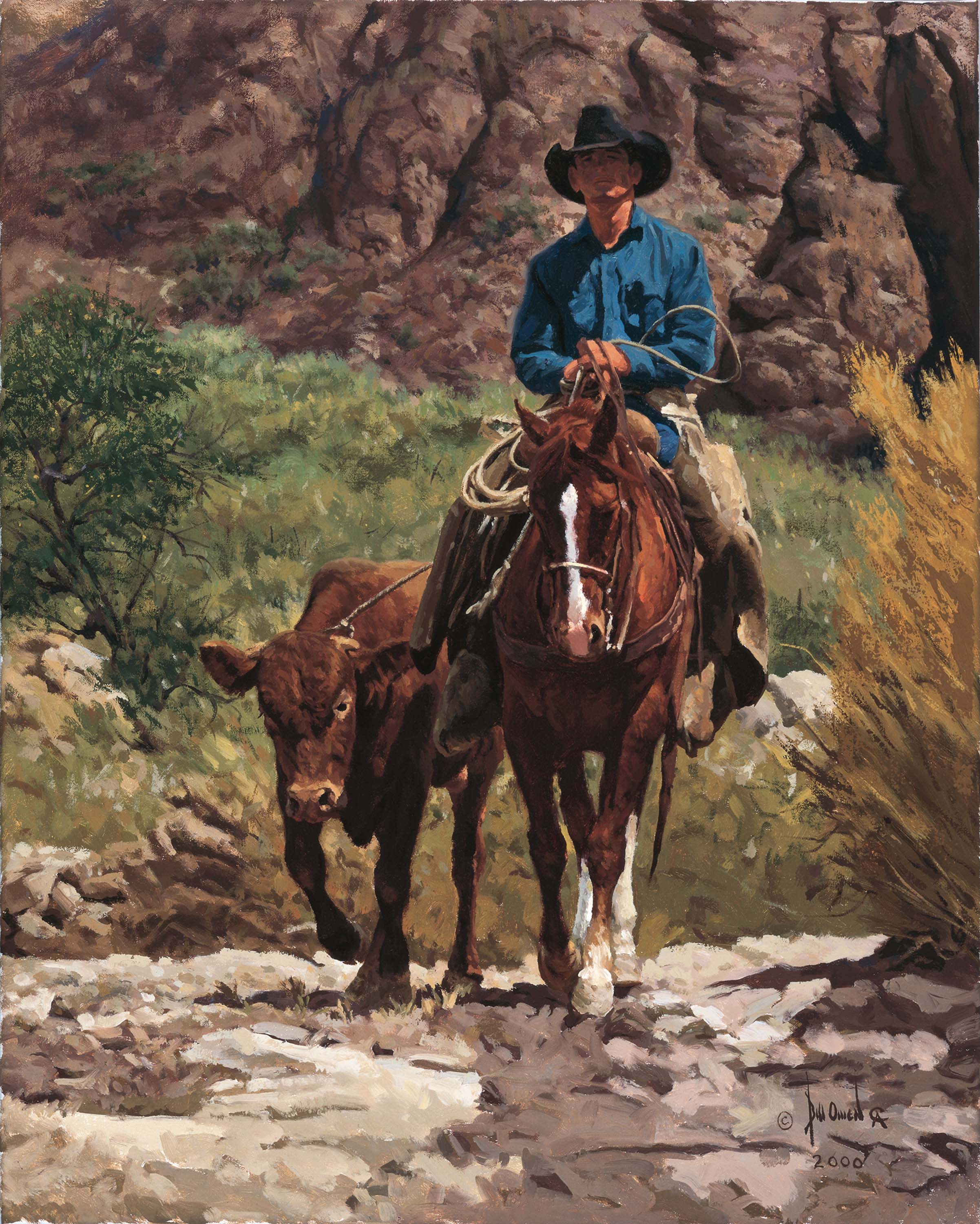

For a few years in the 1990s Bill and Valerie owned, lived on and ran a remote working cattle ranch outside Globe, Arizona. Much of the ranch consisted of extremely rugged country, inaccessible except on horseback or foot. With beautiful rock outcroppings, saguaro, ocotillo and other desert vegetation, it became the setting for such paintings as Leadin’ in a Maverick. The image depicts the real-life experience of finding and bringing in cattle that had been missed by roundups in rough terrain and had turned wild after living on their own. It’s a job that only the most experienced and fearless cowboys will undertake, and these highly respected ranch hands, who were also Owen’s friends, are featured in much of his art.

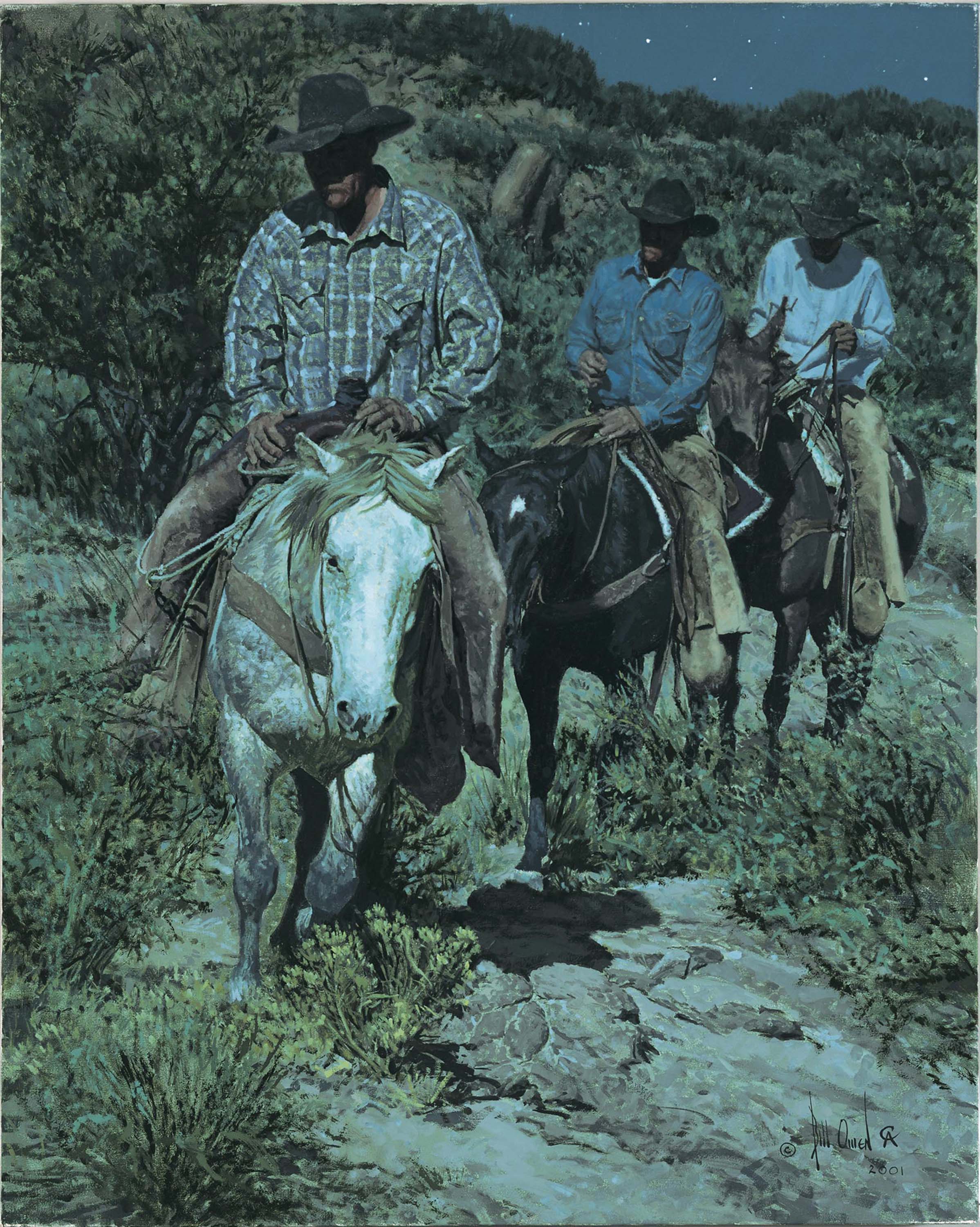

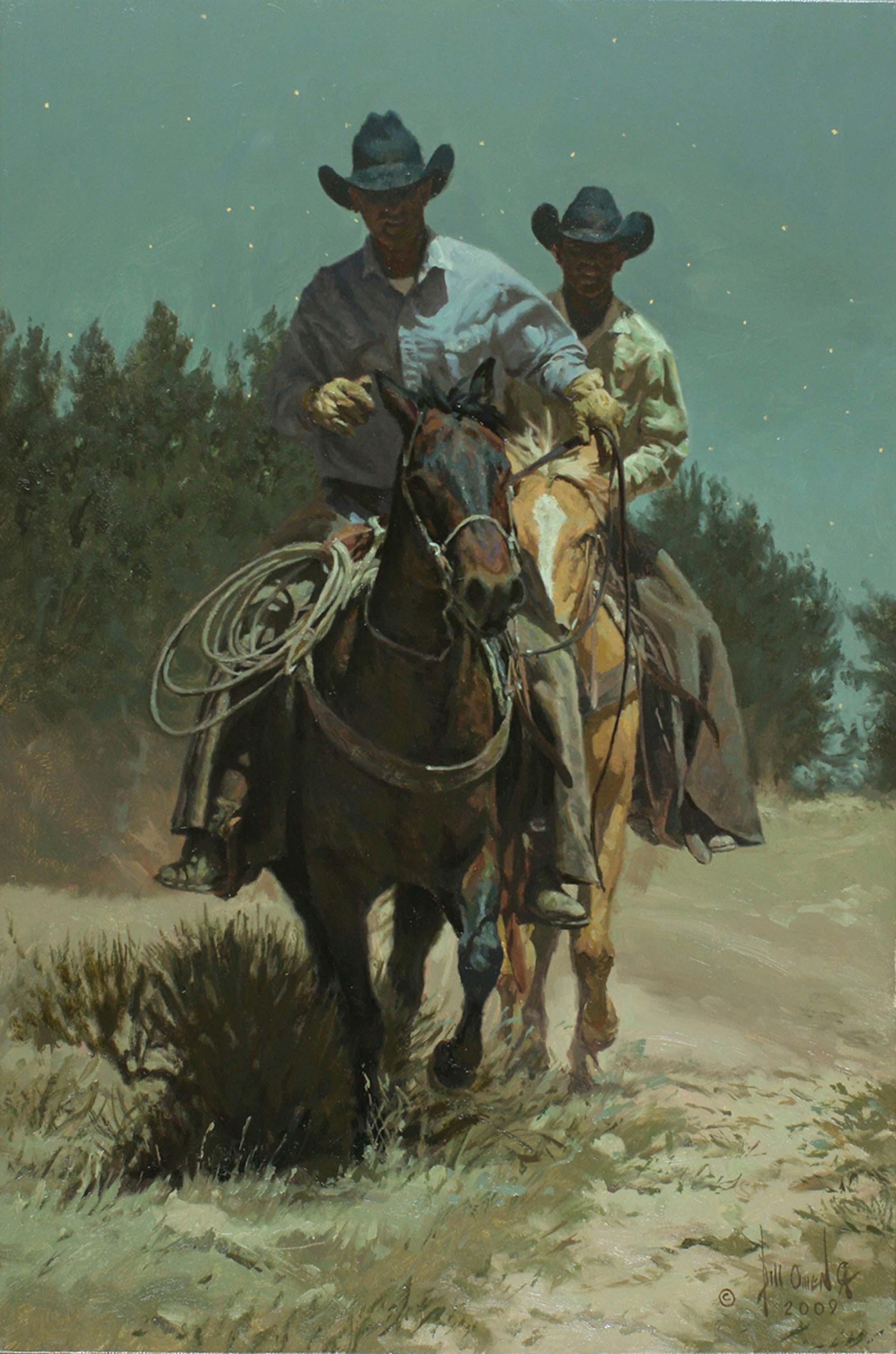

Tim Cox, a longtime close friend and fellow CA member, relates that Owen spent years developing a system of color theory adapted from color use by Tom Ryan and early 20th-century American painter Frank J. Reilly. Owen’s system allowed him to masterfully capture the atmosphere and feeling of any time of day — early morning, midday, sunset and even night. “Since Remington, we’ve acknowledged that nocturnes are extremely difficult to paint,” observes Schroeder, who considers two of Owen’s nocturnes, Moonlighters and Long Day, as prime examples in this respect.

Owen is also highly admired for his depiction of an ever-pervasive part of cowboy life: dust. “The light coming through that dust, many of us thought Tom Ryan was going to be the only guy able to do that, but Bill Owen did it,” Schroeder says of the sunset glow through a diffuse haze of dust in Looking for Short Age Calves.

Yet what stands out most in any discussion of Owen’s art is his unassailable accuracy in the details of cowboy life. Phil Berkebile owns the Great American West Gallery in Grapevine, Texas, which represented Owen exclusively from 2012 until his passing. He remembers the painter talking about Leadin’ Out a Wild One and how some people would not believe a cowboy would cinch a wild bull so close to his horse. “But he said you have to or it won’t work. You run with it and the bull will run, too,” Berkebile recalls. That level of faithfulness to reality reflects the fact that Owen never painted a fabricated scene; every image was inspired by something he witnessed or experienced as a cowboy himself.

Aside from his painting skills, those who knew Bill Owen invariably mention his sense of humor and loyalty as a friend. An annual CA event is its members’ trail ride, a time for being together in the saddle and around the campfire. Grelle remembers the last trail ride Owen took part in, on a Texas ranch in the spring of 2013. As the spread-out string of mounted artists ambled along, Owen guided his horse up and down the line so he could talk and visit with each one. At one point as the riders were winding up a hill, Grelle turned around and spotted Owen on his horse hiding behind a cedar tree, ready to pop out and startle a friend. “That’s a really great memory,” he says, smiling. “Bill was a good guy.”

Cox, who was 17 when he first encountered Owen’s art on the cover of Western Horseman magazine in 1975, has equally treasured memories of quieter moments with his friend. He recalls many evenings on the Owens’ back porch in Kirkland, Arizona, as the two artists talked about life and watched while deer, coyotes or quail came to a rock-lined water feature to drink. “He was thoughtful and had a deep spiritual side,” Cox says. “Bill will be remembered, like Charlie Russell, as one who told the true story of the West and the time that he lived it.”

- “Leadin’ Out a Wild One” | Oil on Canvas | 24 x 36 inches | 2013

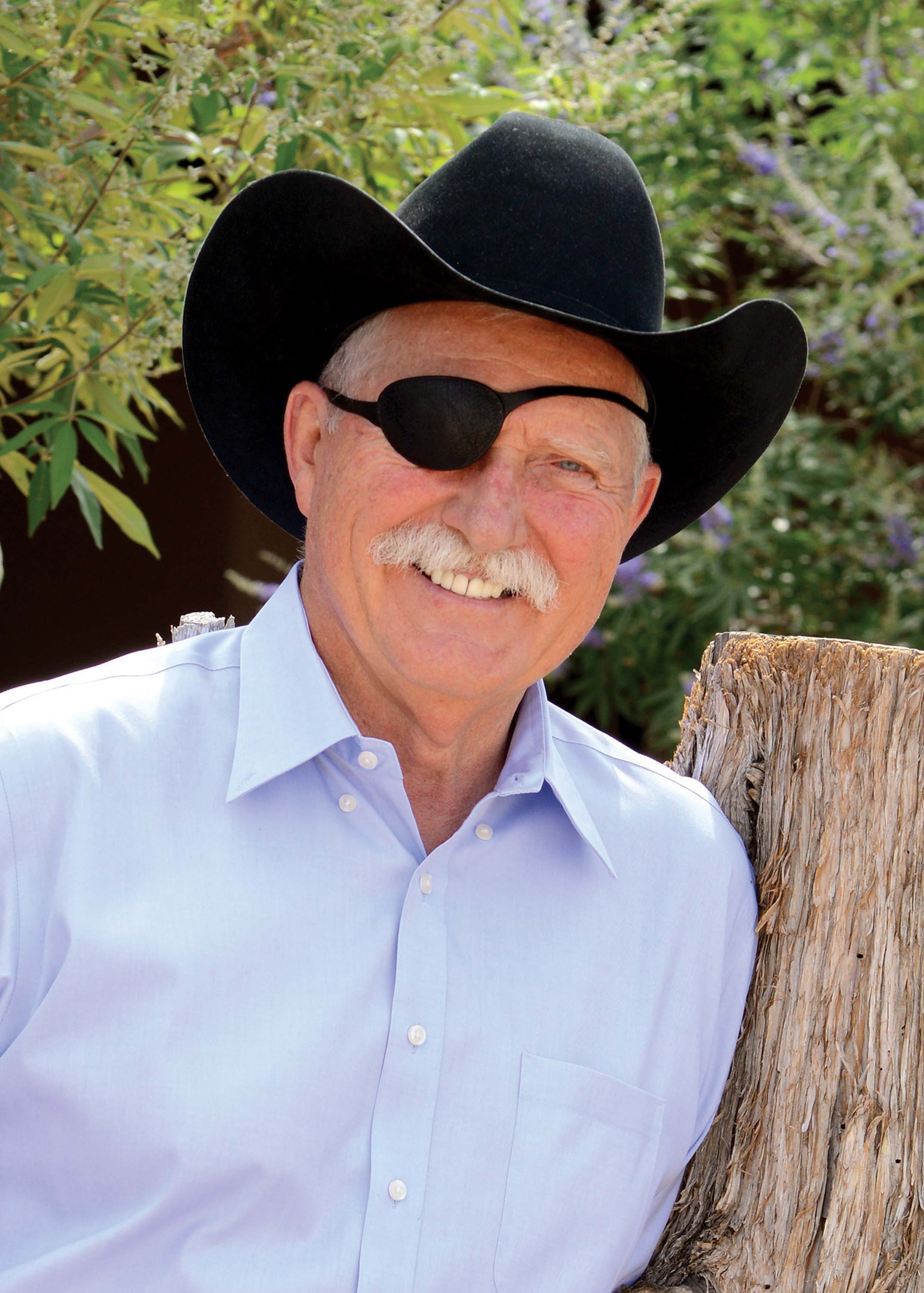

- Bill Owen

- “Caught a Little Deep” | Oil on Canvas | 34 x 34 inches | 2013

- “Leadin’ in a Maverick” | Oi lon Linen | 20 x 16 inches | 2000

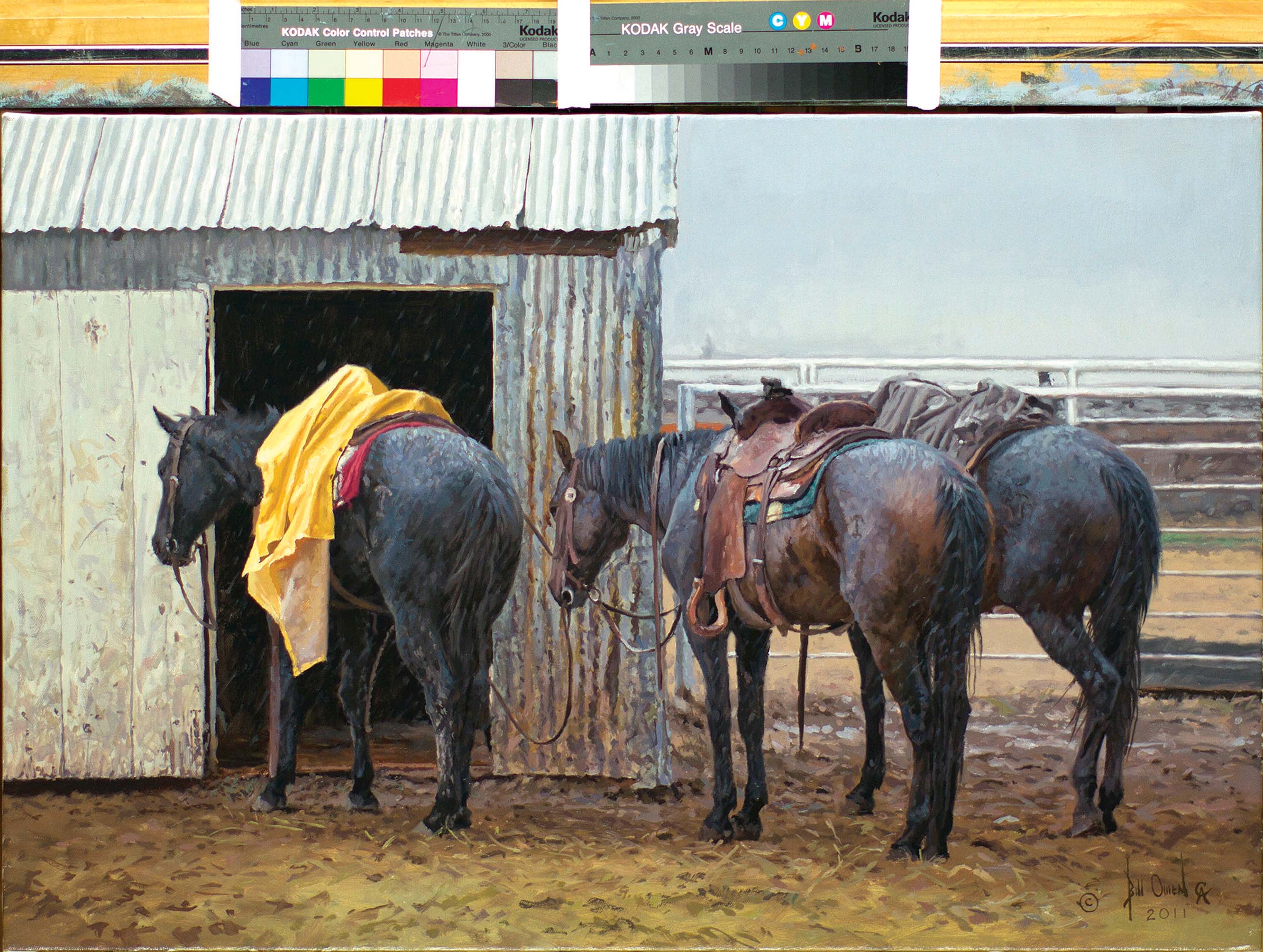

- “Waiting Out the Storm” | Oil on Canvas | 20 x 30 inches | 2011

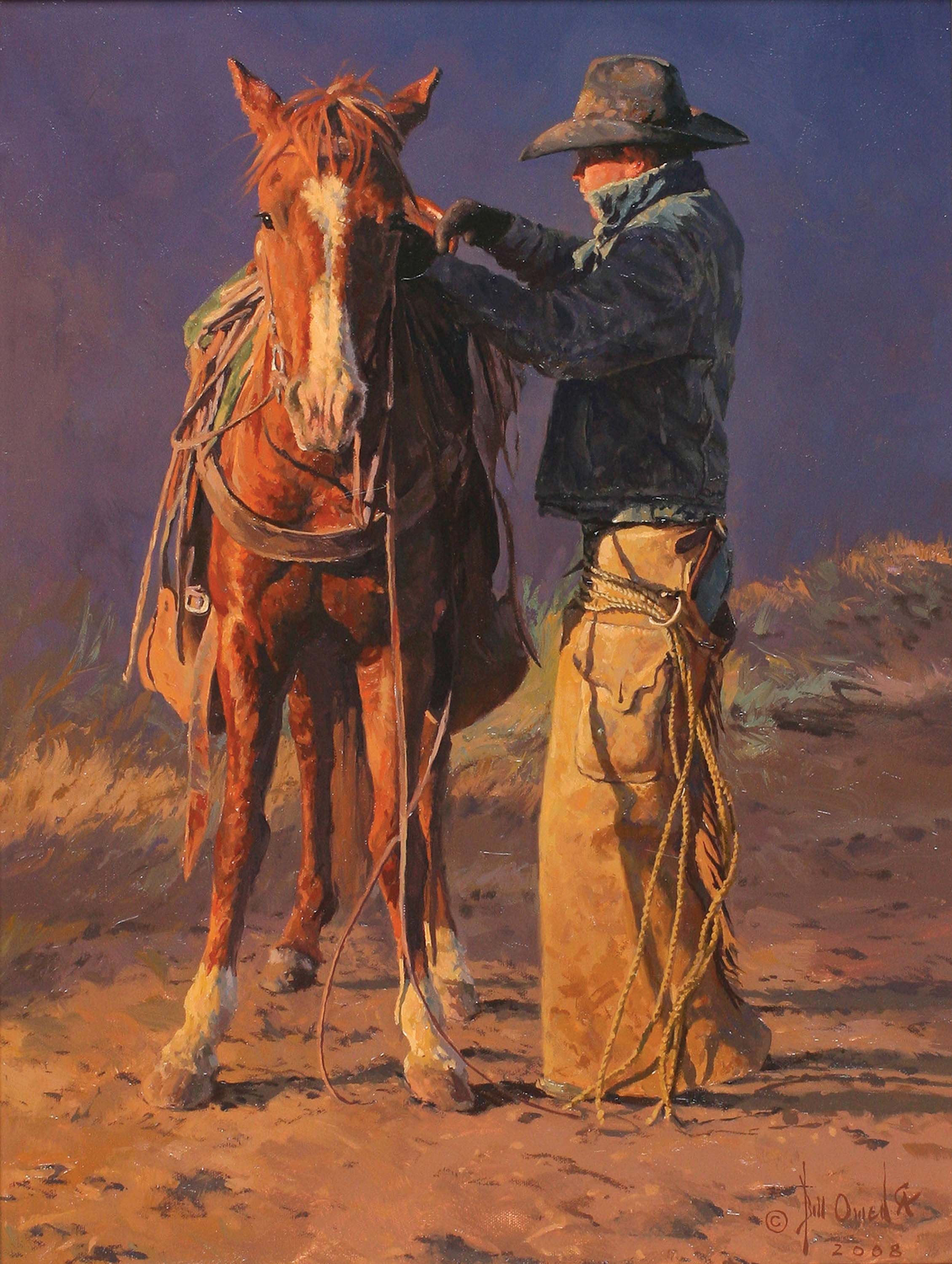

- “Jughead” | Oil on Canvas | 18 x 24 inches | 2008

- “Moonlighters” | Oil on Linen | 24 x 30 inches | 2001

- “Long Day” | Oil on Canvas | 20 x 30 inches | 2009

No Comments