01 Dec Perspective: Gene Kloss [1903–1996]

In an open-top touring car with a water jug strapped to the door, Gene and Phillips Kloss motored over dirt, sand and rough gravel roads from San Francisco to New Mexico during the summer of 1925. It was the young couple’s honeymoon, and their destination was a wooded canyon in the mountains next to Taos. As they unloaded a large tent and camping equipment for a two-week stay, they also hefted a special piece of machinery from the car: a 60-pound printing press, along with a sack of cement. They mixed the cement and used it to secure the press on a large rock. It was the start of a rewarding 69-year marriage, as well as a fruitful seven-decade relationship between an artist and the ancient land and cultures with which she immediately fell in love.

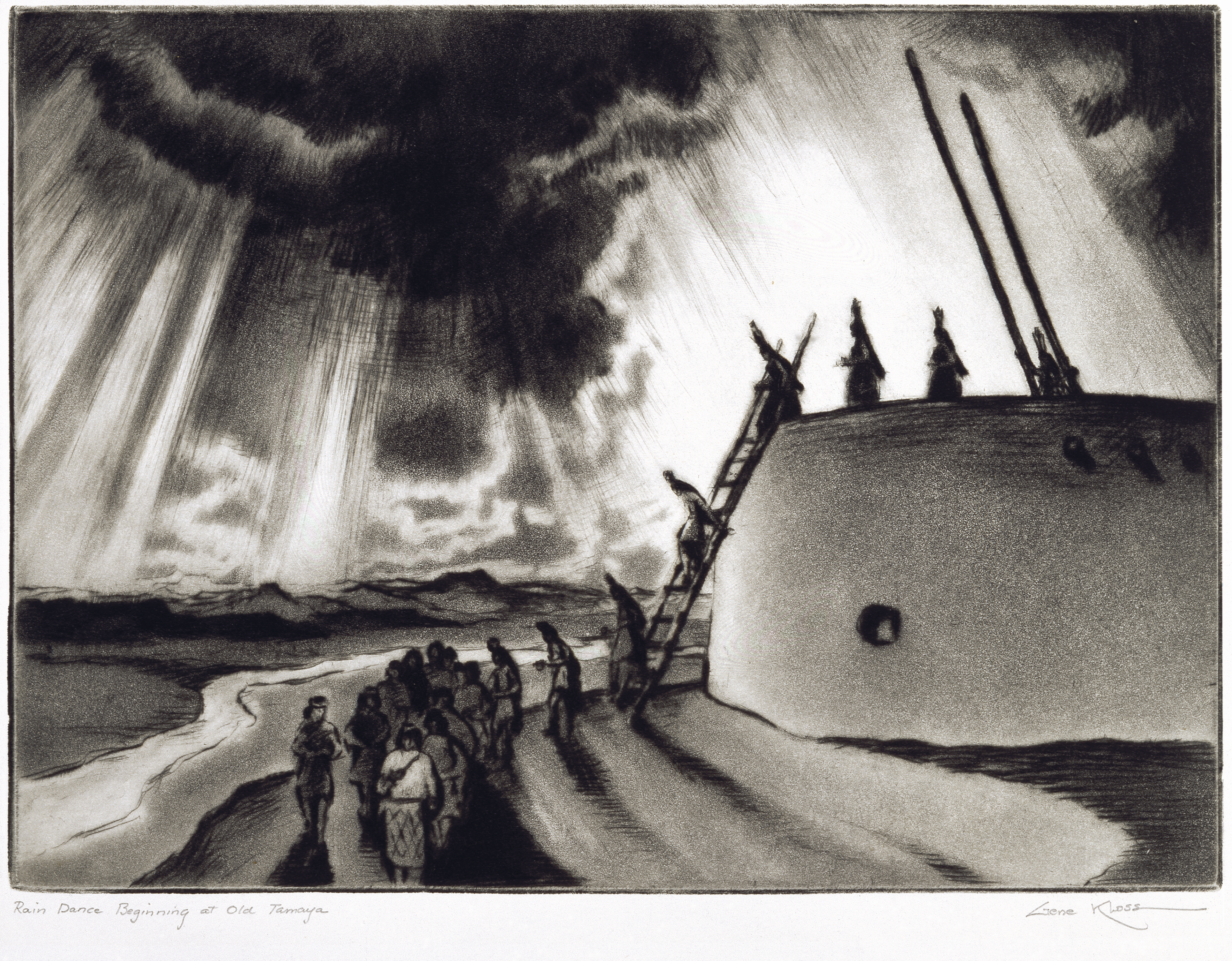

Gene Kloss created more than 625 copperplate images of New Mexico, San Francisco and Colorado during her long, prolific career. Fearless in exploring her chosen medium, she mastered and frequently combined intaglio methods, including etching, drypoint and aquatint, and also painted in watercolor and oils. Kloss’s imagery reflects the strong, respectful and immersed connection she felt in particular with northern New Mexico’s landscape and people at a time when the old ways of Pueblo Indians and Spanish villages remained little touched by the modern world. Almost as soon as she set foot in the state, she declared herself a New Mexican, even though she and Phillips wouldn’t make Taos their permanent home until 1945. With a masterful sense of composition and mood, exquisite tonal gradations and finely etched lines, Kloss was able to convey the drama and mystery of Pueblo dances, the vast scale of mountain landscapes and the quiet beauty of a thick-walled adobe building in the snow.

And she did so without the aid of an assistant, a rare trait among printmakers. Well into her 80s, Kloss still printed every copperplate image in each edition herself. For many years she manually cranked the heavy wheel of a mammoth Sturges etching press, and in her 70s acquired a motorized press — although she kept the old Sturges in case the electricity went out. With editions ranging from five to 250, she single-handedly produced an estimated 18,000 prints over the course of her career. In 1950 she was elected to associate membership in the prestigious National Academy of Design, and in 1972 she was honored by her peers as the first American female printmaker to receive full membership in the academy. Kloss’s art is in the permanent collections of such institutions as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Smithsonian, the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh and the San Francisco Art Museum.

Alice Geneva Glasier, who later adopted the name Gene, was born in Oakland, California, one of three children of a dairy owner. As a child she gained a deep sensitivity toward people and an appreciation for nature’s beauty through the example of her mother, who loved the outdoors and frequently invited less fortunate neighborhood children to join the family on picnic excursions. The future artist also absorbed the independent spirit of an aunt who, in the late 1800s, was among the first women to graduate from the University of California.

With a lifelong love of music and poetry, young Alice studied music and played the piano for silent movies. Her husband, Phillips, was a poet, writer and composer. Together they attended literary salons and chamber music performances in San Francisco and later in Taos. At one such gathering in the Bay Area after she had begun printmaking, Kloss met a young concert pianist and part-time photographer who remarked that in his opinion, her prints exemplified the full tonal range that black-and-white photography should express, from pure white to deep black. Perhaps in part as a result of Kloss’s inspiration, the pianist eventually shifted his focus from music to photography. His name was Ansel Adams.

Kloss’s initial encounter with printmaking took place during her senior year at the University of California at Berkeley, where she graduated with honors in fine art in 1924. After learning a little about the etching process, she experimented and “messed up my mother’s kitchen from one end to the other,” as she related to Sylvia Loomis in a 1964 oral history interview, archived in the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art. Determined, she purchased a $2 book on etching and tried again, taking the etched copperplate to her professor. She later told Loomis: “He inked it and I turned the wheel of the press. He looked at me and said, ‘If this is your first etching, you are going to be an etcher.’”

Kloss never stopped experimenting. She turned to whichever intaglio method, or combination of methods, best suited her subject: from windswept cypress trees on the Northern California coast to processions of the secretive Penitente Brotherhood religious sect in northern New Mexico. “Gene continually pushed herself to try different things, to attempt different effects and through the process to make light and dark, shades and brightness, speak on their own terms,” notes Jerry Smith, Ph.D., curator of American and Western American art at the Phoenix Art Museum, which celebrates Kloss’s life and art with an exhibition opening January 11. In Light and Shadow: Southwest Prints by Gene Kloss runs through April 6.

Taos native Eugene (Gene) Sanchez, with the assistance of his wife, Jules, spent 13 years compiling a remarkable two-volume catalogue raisonné of Kloss’s art. Gene Kloss, An American Printmaker: A Raisonné was published in 2009 by the University of New Mexico Press. Sanchez’s mother was the late Mary L. Sanchez, founder and owner of Gallery A in Taos. The gallery, now closed, carried Kloss’s work exclusively for more than 25 years, during which time Mary Sanchez and Gene Kloss became close friends. A talk by Gene Sanchez is set for February 19 at the museum in conjunction with the show.

Following the Klosses’ honeymoon camping visit, the couple lived most of each year in Taos, returning periodically to San Francisco to be with their widowed mothers. At first they rented an old adobe house for $10 a month, carried water from a spring, cooked on a woodstove, and “worked incessantly,” as Phillips explained it in the preface to a book of his wife’s etchings. Gradually they acquired 40 acres near Taos, settling there permanently except for a five-year sojourn in Colorado in the late 1960s. Phillips died in 1994.

Longtime collector John Armstrong, who began purchasing Kloss’s prints in 1979, remembers the artist as the personification of pioneer spirit. “She was strong, determined, and worked hard at her art,” Armstrong wrote in an essay in the raisonné. (Over the years Armstrong has donated more than 450 Kloss prints to the Sangre de Cristo Arts Center in Pueblo, Colorado, which now holds the single largest collection of her art, along with her etching tools and her final press.) The Sanchezes knew Kloss as a plain-dressed woman with a dry wit who was much more interested in hiking in the mountains with Phillips — often carrying a copperplate and etching directly into it with a drypoint tool — than being part of the Taos social scene. She was acquainted with members of the Taos Society of Artists, including Ernest Blumenschein, Joseph Henry Sharp, Bert Phillips and E. I. Couse, but was not closely involved with their group. This was at least in part, she believed, because she was younger and a woman.

Yet Gene and Phillips established close, trusting friendships with many Taos Pueblo Indians, whose ancient adobe homes, dances and faces were the subject of some of her most powerful work. The Klosses attended dances so regularly that once when they missed one, their Pueblo friends sent someone to their home to make sure they were okay. Kloss never owned a camera, but constantly sketched and relied on an impeccable visual memory. “Gene makes memory sketches of Indian activities from her own point of view, with respect for the unknowable Indian point of view,” Phillips wrote.

What the Klosses knew without question was their unmatched good fortune at being in northern New Mexico at that point in time, when Taos was in its “primeval glory,” as Phillips called it. Sanchez notes that it was “extremely important to Gene that what she did became historical record, to make sure someone preserved a memory of the dances and land, because she had a sense that the world would spiral out of control.” Throughout her career she maintained a regional, representational focus, even as much of the art world turned to Modernism and abstraction. Yet Kloss’s style, while changing little over the decades, contains elements that can be seen as Modern. A sophisticated sense of composition and design were as central to her approach as the subjects she depicted, asserts Smith, of the Phoenix Art Museum. “Certainly her knowledge of Modern art, by osmosis, allowed her to loosen up ideas of design that would not have been accepted in the 19th century but were accepted in the 20th,” he observes. “I truly believe that had she pursued painting with the same rigor, hard work and dedication as she did with printmaking, she could be as well known today as Georgia O’Keeffe.”

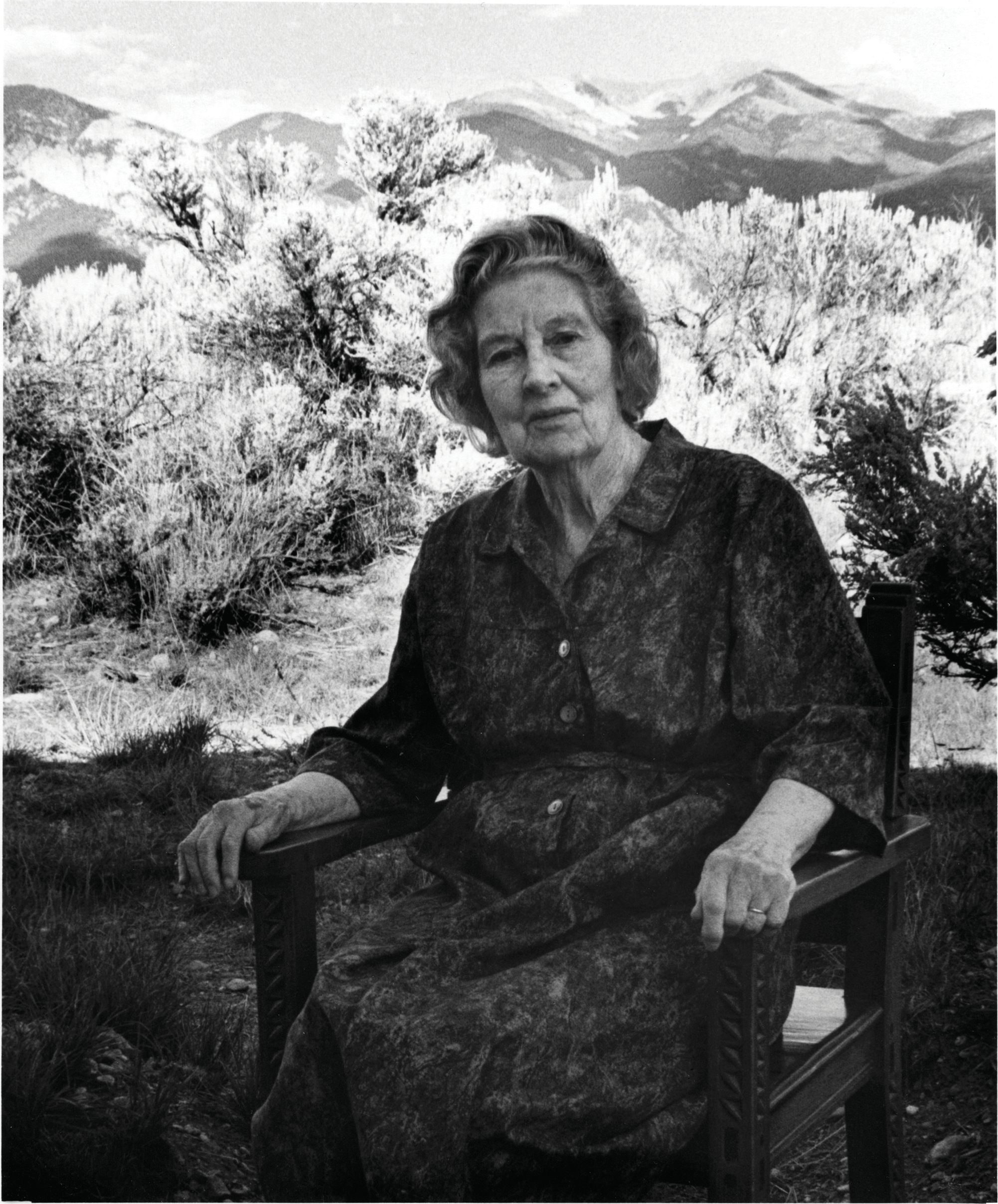

- Gene Kloss. Photo: Carolyn Swain Palmer | Courtesy of Wiz Allred, Desert Moon, Taos, NM

- “Rain Dance Beginning at Old Tamaya” | Drypoint and Aquatint | 7.875 x 11.375 inches | 1956 | Courtesy of Wiz Allred, Desert Moon, Taos, NM

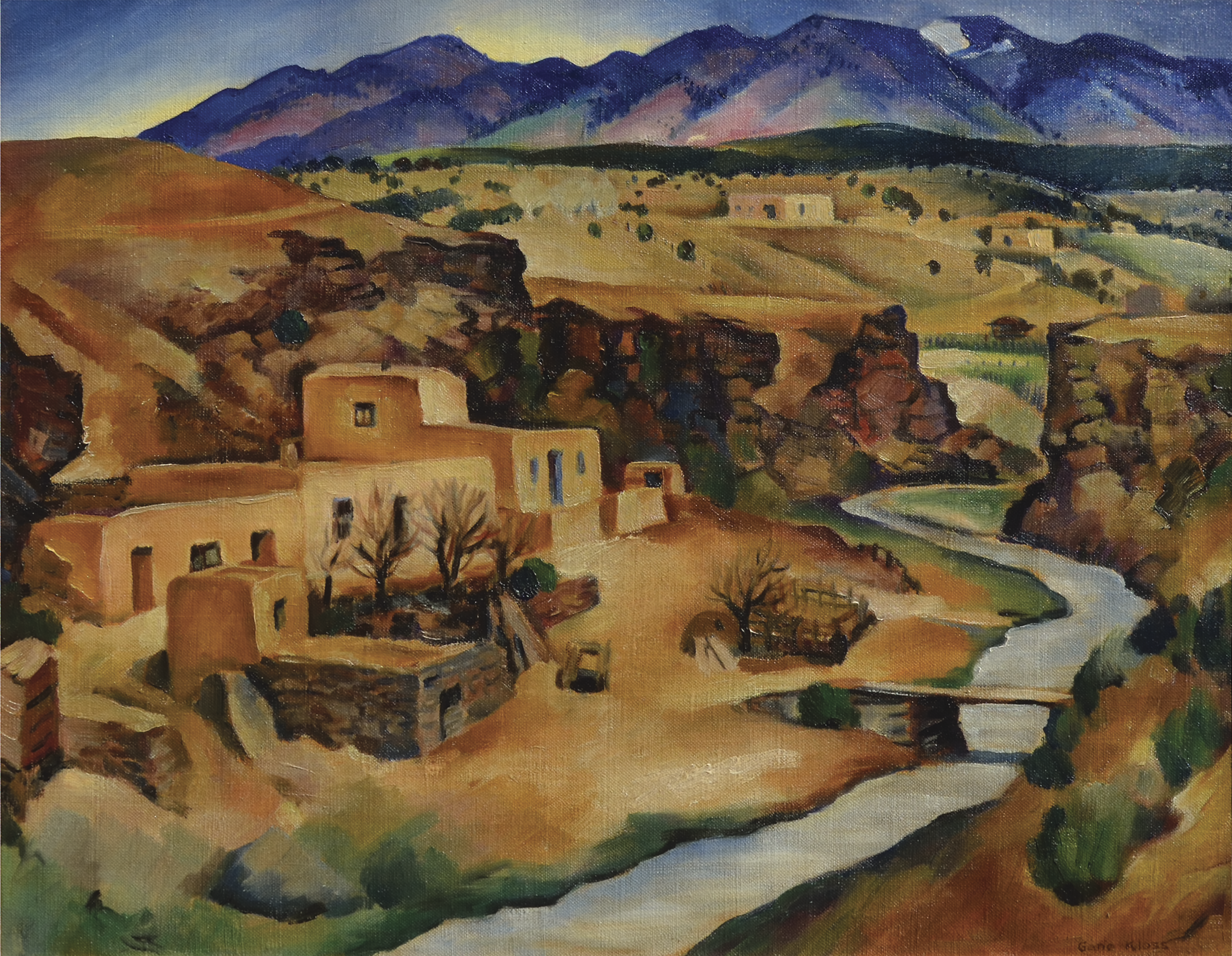

- “Winter in Telluride” | Etching and Drypoint | 11.75 x 14.75 inches | 1968 | Courtesy of Wiz Allred, Desert Moon, Taos, NM

No Comments