04 Aug Perspective: Group f/64

When a handful of San Francisco area photographers got together one night in 1932 for a little bootleg grain alcohol and camaraderie, there was something bigger than socializing on their minds. Each of them — Edward Weston [1886–1958], Willard Van Dyke [1906–1986], Ansel Adams [1902–1984], Imogen Cunningham [1883–1976] and a few others — was ready to turn the page for photography on the West Coast. And each was committed to an aesthetic and an approach to the camera that was radically different from the prevailing photographic style in California at the time.

Banding together to promote their vision and seek professional recognition during the economically troubled years of the Great Depression, the photographers emerged from that gathering as an informal collective with the name Group f/64. The association itself was short-lived; by 1935 its original members were beginning to diverge professionally and geographically. Yet individually and collectively over the next few decades, f/64 would exert vast influence on the direction of 20th-century American photography, providing important momentum to establish the medium as an art form.

The photographic style that Group f/64 intended to unseat was one that many of its members had previously embraced. Known as pictorialism, it was popular in Europe and the United States during the latter part of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Pictorialism featured gauzy, romantic, soft-focus images, often hand-manipulated to resemble drawings or etchings. The movement was an attempt to draw attention to photography as expressive, rather than simply a means of documentation. By the late 1920s, its popularity was waning in Europe and New York, where Modernism was becoming the prevalent aesthetic. But California was a weeklong train journey from New York, and a lag time existed in artistic exchange between the two coasts.

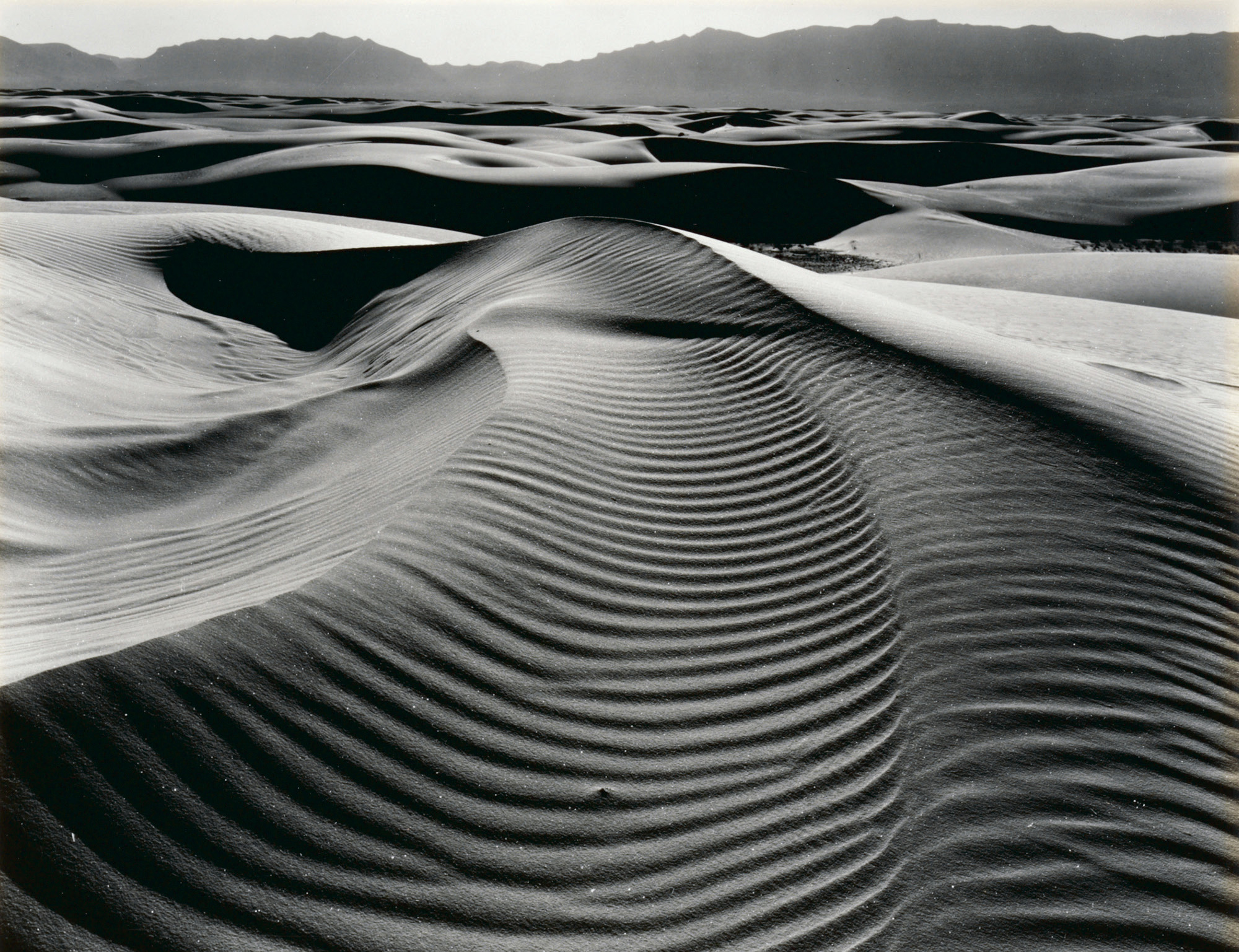

Group f/64 members were using the camera in an entirely different way. They wanted to allow the intrinsic qualities and parameters of the medium to dictate the artistic result. The group’s name came from the large-format camera’s smallest aperture, f/64, which provided the greatest depth of field and allowed the photograph to be in sharp focus. Pictures were printed on glossy paper using contact printing, and images were crisp, intentionally composed and contained a full range of tonal contrasts. Group f/64 members penned a manifesto outlining their vision, which they termed “straight photography.”

“It was about embracing the technical and mechanical properties innate to the camera, as opposed to disguising the medium,” notes Amy Scott, chief curator at the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles, California. “This was what they called ‘pure’ or ‘straight’ photography, in which the process mattered more than what was seen through the lens. They would crop and frame to maximum abstract potential. Group f/64 members were also all darkroom technicians, which is an art in itself.”

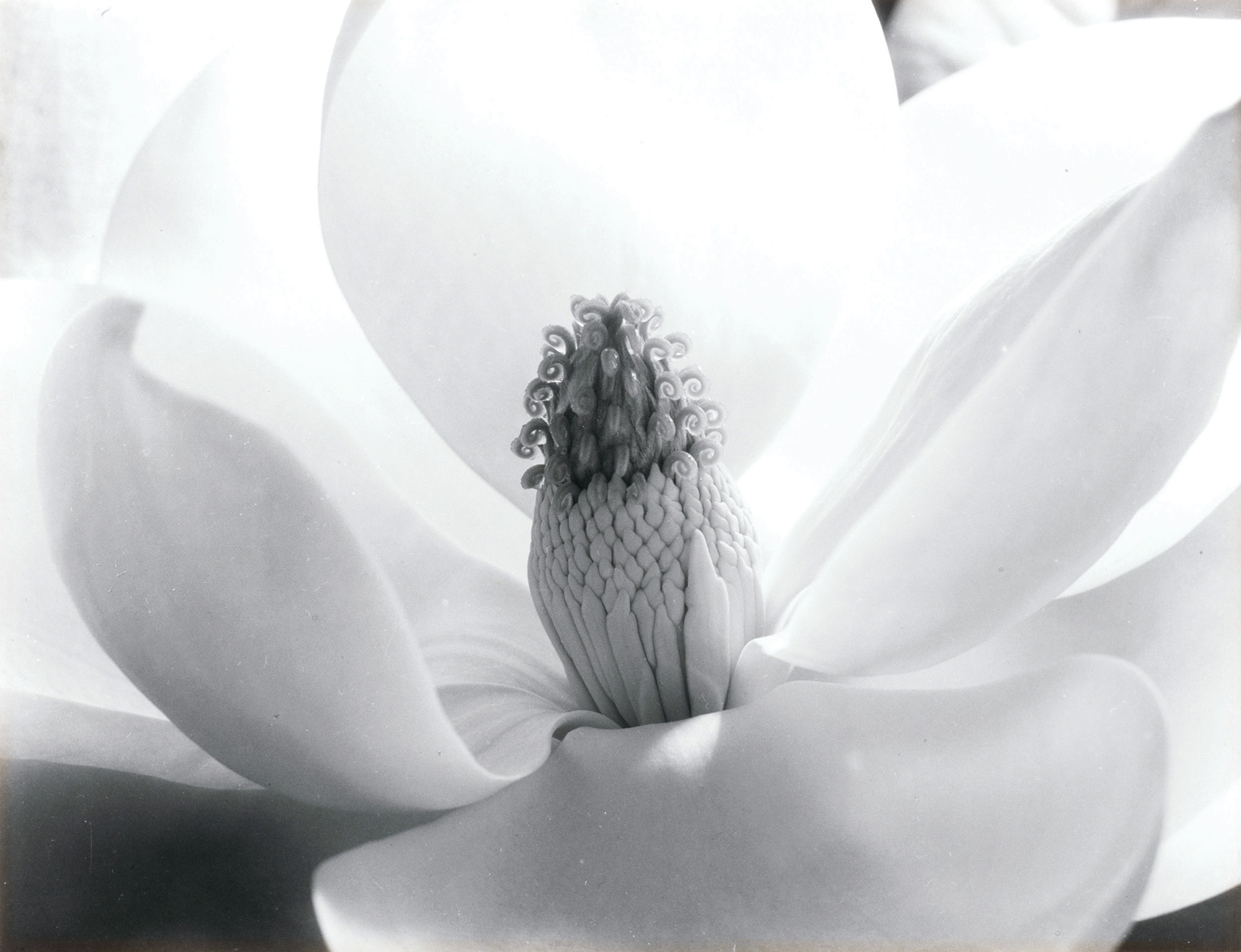

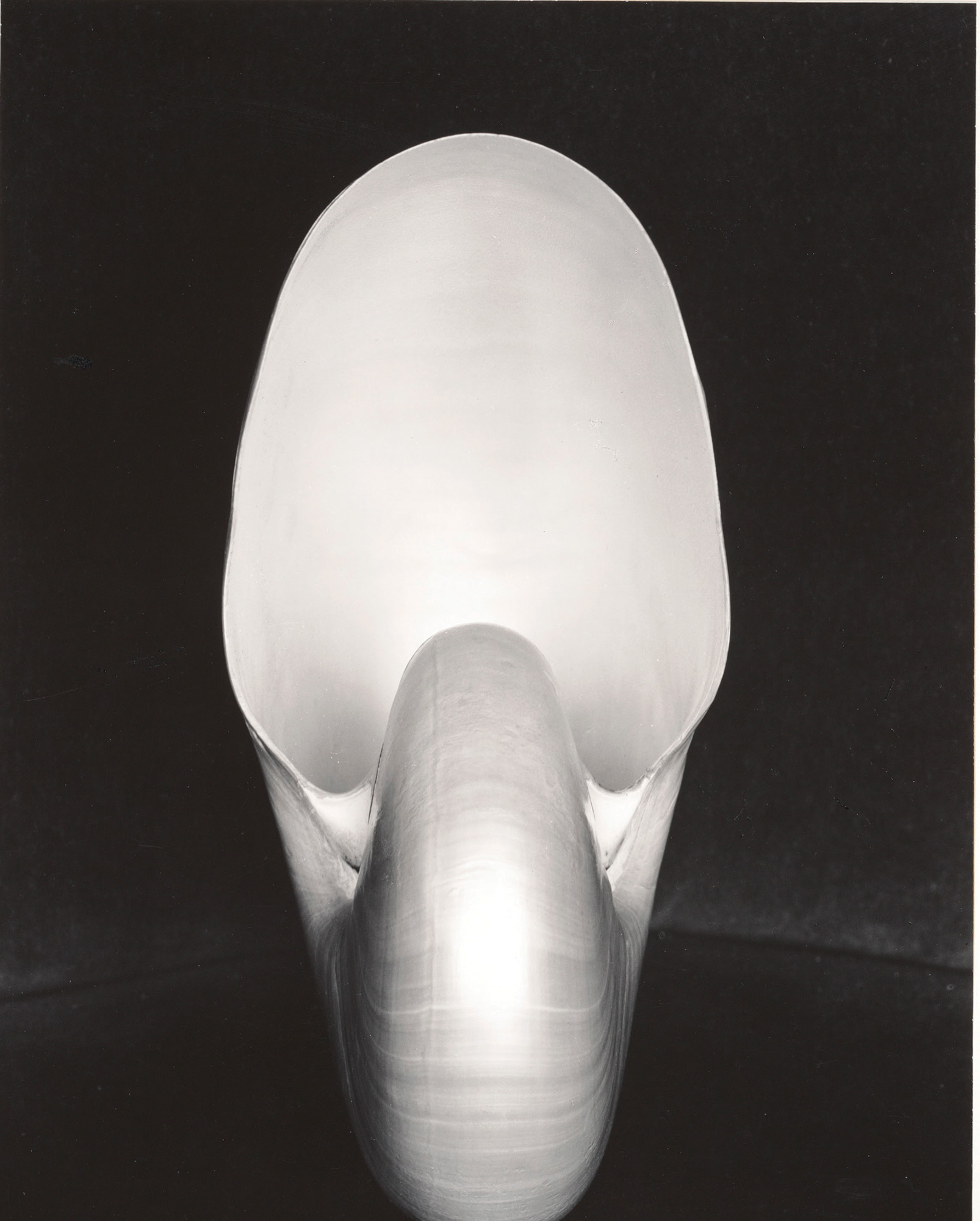

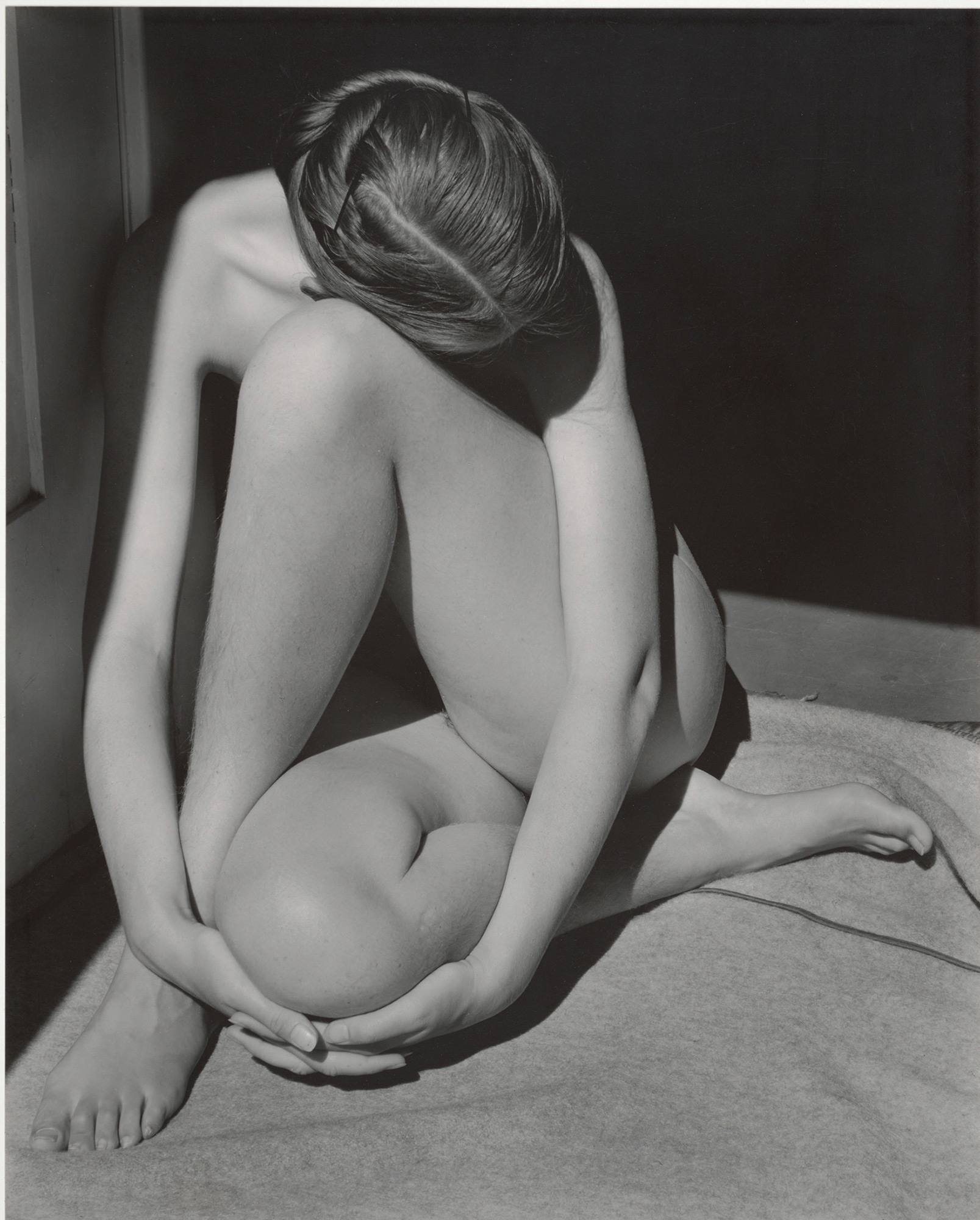

The group sought to present the camera’s “vision” as clearly as possible. As founding member Edward Weston expressed it, “The camera should be used for a recording of life, for rendering the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself, whether it be polished steel or palpitating flesh.” Their efforts resulted in striking photographs, including still lifes, which often took the form of close-ups of plants and other abstracted forms from nature, landscapes, portraits and nudes.

Works by five seminal Group f/64 members are part of a recent exhibition that runs through January 8, 2017, at the Autry Museum. Revolutionary Vision presents photographs by Weston and his son, Brett Weston, Adams, Cunningham and Van Dyke. Their work is presented in dialogue with large-scale color images by contemporary landscape photographer Richard Misrach [b. 1949]. The exhibit’s nearly 90 photographs demonstrate the contrast between the early-to-mid-20th-century voice of optimism and confidence, as exemplified by Adams’ idealized wilderness landscapes, against Misrach’s images that are gorgeous yet hint at environmental decay as a result of overuse and misuse.

Also on view this fall is an exhibition of photography by Edward Weston at the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California. The show highlights images related to Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, a 1941 deluxe edition of which was illustrated with Weston’s photography. It opens on October 22 and runs through March 20, 2017.

Weston grew up in Chicago and was given his first camera by his father at age 16. In 1908, he attended the Illinois College of Photography in Effingham. Most of his career was spent in California, where he initially worked as a portrait photographer and ran his own portrait studio for many years. In the early 1920s, he traveled to New York City and met photographer and gallery owner Alfred Stieglitz, who was ardently championing photography as art.

From 1923 to 1926, Weston ran a photographic studio in Mexico City, where he was exposed to Cubism and Mexican Social Realism and earned the admiration of the famed Mexican muralists. These experiences helped point him toward a new conception of photography as modern art. Back in California, he began producing what became his most well-known work: stunning abstracted close-ups of vegetables, seashells and other natural objects, as well as nudes and landscapes, in particular the Oceano Dunes on the California coast. His photographic philosophy at this point was completely aligned with that of his fellow artists with whom he would gather in 1932.

The somewhat younger Ansel Adams, meanwhile, came of age in San Francisco with a passion for the natural world, having spent countless boyhood hours wandering the wild beaches and creeks near the Golden Gate. Photography entered his life as a teen when his parents gave him a Kodak No. 1 Box Brownie camera. Soon after, the Yosemite Valley became his first, and lasting, photographic muse. In 1927, Adams met Weston, and the two became friends and colleagues. By 1930, Adams was abandoning pictorialism and becoming ripe to serve as an enthusiastic advocate of “straight” photography.

Perhaps influenced by the progressive nature of the labor and Marxists movements of the time, Group f/64 was surprisingly gender inclusive for its era. Along with Imogen Cunningham, its original seven members included German-born photographer Sonya Noskowiak [1900–1975]. Among the invited photographers in its inaugural exhibition were Consuelo Kanaga [1894–1978] and Alma Ruth Lavenson [1897–1989].

Cunningham was already an established photographer by the time Group f/64 was founded, having had her first one-artist exhibition in 1914 at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences. She was raised in Seattle and studied chemistry at the University of Washington as a foundation for darkroom skills. Following graduation she worked for a time in the studio of Edward S. Curtis [1868–1952], famed photographer of American Indians. Soon after, she set up her Seattle studio and exhibited frequently into the 1920s, often in the pictorialist style, before turning her camera to her first sharp-focus close-ups of plants.

Within months of Group f/64’s founding, Edward Weston persuaded the M.H. de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco to provide space for the group’s first exhibition on November 15, 1932. Core members — who also included John Paul Edwards [1884–1968] and Henry Swift [1891–1962] — invited Kanaga, Lavenson, Preston Holder and Weston’s son, Brett, to be part of that show. Group f/64’s approach continued to gain recognition over the years as members opened galleries in San Francisco and Oakland, led workshops, wrote articles and published photographs in magazines. Today, the most complete collections of prints by Group f/64 members are housed at the Center for Creative Photography on the University of Arizona campus in Tucson and at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

In 1940, thanks in part to efforts by Adams, the first museum photography department in the United States was established at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, with Beaumont Newhall as the department’s first director. This development underscored the success of photographers, including Group f/64 and Stieglitz, in getting the medium recognized as a true art form. In a 1933 article for Camera Craft magazine, Adams noted that the group’s approach to photography as art allowed for enormous variety in subject matter and styles. “Our individual tendencies are encouraged; the Group Exhibits suggest distinctive individual view-points, technical and emotional, achieved without departure from the simplest aspects of straight photographic procedure,” he wrote.

In many ways, images by Group f/64 members reflected a Modernist aesthetic and philosophy, which eschewed 19th-century values of representation and romanticism in art. Edward Weston’s photographs of vegetables, nudes or dunes, for example, often were abstracted to the point of visual disorientation of subject and sense of scale. Similarly, Cunningham’s close-up botanicals and Van Dyke’s industrial imagery draw the eye to composition, contrast, patterns and forms.

“Their work related to issues emerging in Modernist art at the time: technique over subject, and the idea that art should divest itself of anything that doesn’t refer to the essential elements of the medium,” says Jennifer A. Watts, curator of photography at the Huntington. “Photography, at the time, was supporting that through the unique and specialized abilities the camera brings to the table.”

Because the camera is a machine, Group f/64’s focus on its inherent capabilities also suited the optimistic American outlook at the time regarding progress and industry. Especially during the Depression, the country needed a hopeful vision of its future, Scott points out. “Adams believed that what they were doing had social value, by providing uplifting, positive views,” she says. Through their images, teaching and writing, Group f/64 members helped popularize American photography over the longer term, both as fine art and as a medium eventually available to all. “Their influence can’t be overstated,” adds Watts.

- Ansel Adams, “Half Dome, Blowing Snow, Yosemite National Park, California” | Gelatin Silver Print | circa 1955 © 2016 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

- Edward Weston, “Shell” | Gelatin Silver Print | 1927 | Collection Center for Creative Photography, © 1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

- Richard Misrach, “Battleground Point #41 | C-print | 1999 | © Richard Misrach, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

- Edward Weston, Nude | Gelatin Silver Print | 1936 | Collection Center for Creative Photography, © 1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

- Brett Weston, “Untitled” (Dunes, White Sands, New Mexico) Gelatin Silver Print | 1946 | © The Brett Weston Archive, brettwestonarchive.com

- Willard Van Dyke, “Ventilators” | Gelatin Silver Print | 1933 Bank of America Collection

No Comments