11 Jan Perspective: Helen Henderson Chain [1849–1892]

Anyone who has hiked Colorado’s high country or ascended any of its 14,000-foot peaks may have trouble imagining this: a petite woman scrambling over rocky outcroppings and following trailless ridges high above tree line while dressed in a long, heavy skirt, petticoat and a corset, hefting a plein air easel and paints.

In an era when female artists were generally fussing over “ladylike” subjects, such as floral still lifes, Helen Henderson Chain [1849–1892] intrepidly immersed herself in her subject of choice. The artist experienced first-hand the West’s extraordinary expanses and painted romantic, panoramic depictions of what she saw. At the same time, before their untimely deaths, she and her husband helped nurture a budding artist community in the cultural wasteland of the late 19th-century boomtown, Denver, Colorado. They also quietly, and mostly anonymously, spread philanthropic good.

As Colorado’s first female long-term resident artist, Helen settled in Denver in 1871 with her husband, James Albert Chain [1847–1892]. The newlyweds had met in Jacksonville, Illinois, where Helen studied painting and earned a liberal arts degree from Illinois Female College (now MacMurray College) and subsequently taught there for two years. James had returned to his home state after a stint of cowboying in Colorado in a partially successful attempt to improve his fragile health. Soon after their wedding, the couple and James’s widowed mother headed to Denver.

It wasn’t Helen’s first experience in the West. Born on July 31, 1849 in Indianapolis, Indiana, she spent her early years in the Northern California town of Antioch, where her father was a doctor. There she was exposed to people of many races, languages and nationalities, seeing them with a child’s open-mindedness that later would guide a compassionate desire to help those in need. The experience also kindled a lifelong fascination with travel, to the point that, as an adult, her family affectionately nicknamed her “Trot.”

When she was 13, her mother died and her father sent Helen and her younger brother back to Indiana to live with an aunt. Meanwhile, her future husband grew up in Illinois, clerking in general stores as a young man and attending Illinois College. He and Helen were married in March 1871.

Soon after the couple settled in Denver, James (joined by friend, S.B. Hardy) opened Chain & Hardy’s Parlor Bookstore. The enterprise was much more than a bookstore. It bound and published books of local interest, sold stationary and, most significantly, carried art supplies. Over time, Chain & Hardy’s became a magnet and gathering place for virtually all artists living in or traveling through Colorado.

“Helen was very interested in the arts. She was a promoter of art, she talked art, she lived art,” remarks Stanley Cuba, associate curator at Denver’s Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art. Cuba has studied the artist for almost 30 years and has written and lectured on her life and work.

In Denver, Helen began painting more seriously, soon carrying her paints into the nearby forests and foothills and up towering mountains. In the process, she became the first woman of European ancestry to summit several of Colorado’s 14,000-foot peaks. Her quickly developing painting skills were noticed and encouraged by artist friends she and James met through the bookstore, including Thomas Moran and Hamilton Hamilton, a painter from back East.

In 1877, two years after Moran painted his famed Mountain of the Holy Cross, Colorado, Helen produced her vision of the mountain, more commonly known as Mount of the Holy Cross. She became the first woman to paint the iconic landmark and the first European American woman to reach its 14,009-foot peak.

“There’s a freshness in Helen’s work that comes from her personal involvement in the landscape. Mount of the Holy Cross was a quintessentially important subject for her,” notes Denver-area resident Deborah Wadsworth. Wadsworth and her husband, Warren, have collected and studied historic Colorado art for more than 40 years, and Wadsworth has guest-curated a number of shows on early Colorado artists. In 2014, she guest-curated an exhibition on Helen Henderson Chain at the Denver Public Library. It was the library’s first single-artist show to honor the little-known painter.

Along with exploring many parts of Colorado, traveling with James by horseback and on foot, Helen often journeyed to California to visit her father and siblings. Each time, she followed a different route, sketching and painting such magnificent landscapes as Yellowstone and Yosemite. She is thought to be the first female artist to set up her traveling easel at the Grand Canyon. The Chains also spent time in Mexico and New Mexico. On several occasions they traveled in Pullman train cars in the company of mutual friend and acclaimed photographer, William Henry Jackson.

In 1882, two of Helen’s paintings of Native American Pueblos from her New Mexico trips were juried into the prestigious National Academy of Design exhibition in New York City. “To be selected for a leading New York exhibit speaks to the quality of her work, especially as a resident of Denver, which at the time had no established art schools with stature outside of Colorado,” Cuba says.

In the 1870s and 1880s, Helen’s work also was chosen for inclusion in the Centennial Exhibit in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and the National Mining and Industrial Exposition in Denver, where it hung alongside paintings by Albert Bierstadt, Moran, Hamilton and other eminent contemporaries. In addition, six of her Colorado landscapes were purchased for reproduction as chromolithograph prints by East Coast publisher Louis Prang, who also reproduced works by Bierstadt and Moran.

While sketching, painting outdoors and working in her studio, Helen also refined her skills through formal and informal instruction. During one of the Chains’ visits to the East Coast, she studied with Hudson River School painter George Inness in New York. On travels in Europe, she copied masterpieces in museums and sketched and painted endlessly. Back in Denver in the late 1870s, she became a student of art instructor W.F. Porter. When Porter died suddenly, Helen took over teaching his classes, using a room in the bookstore and frequently leading her students on sketching and painting excursions in the Colorado wilds. Among her students was a young man named Charles Partridge Adams, who worked as a clerk in the bookstore before taking up painting classes with Helen and becoming a good friend. The two often painted outdoors together, and Adams went on to become one of Colorado’s most well-known landscape painters.

With no children, the Chains funneled their human compassion and finances into charitable causes, both independently and through Denver’s Central Presbyterian Church. They sponsored children to attend school and sent Chain & Hardy’s employees and others to the couple’s pristine mountain property in Buena Vista, Colorado, for health respites — all anonymously. “They believed in doing good but they believed very strongly that doing good was not for aggrandizing themselves,” Wadsworth says. “So it wasn’t until their funerals that the public found out what they had done.”

Having been exposed to diverse populations as a child, Helen felt a particular compassion for Denver’s impoverished underclass of Chinese immigrants. She established a school in a back room of the bookstore to teach them reading, writing and conversational English. Known as the Chinese School, the project grew substantially over time, expanding to include Japanese and other Asians, and continuing for more than 50 years. Describing Helen’s reputation in the community, Cuba says, “People thought of her as a lovely, caring person, a wonderful individual.”

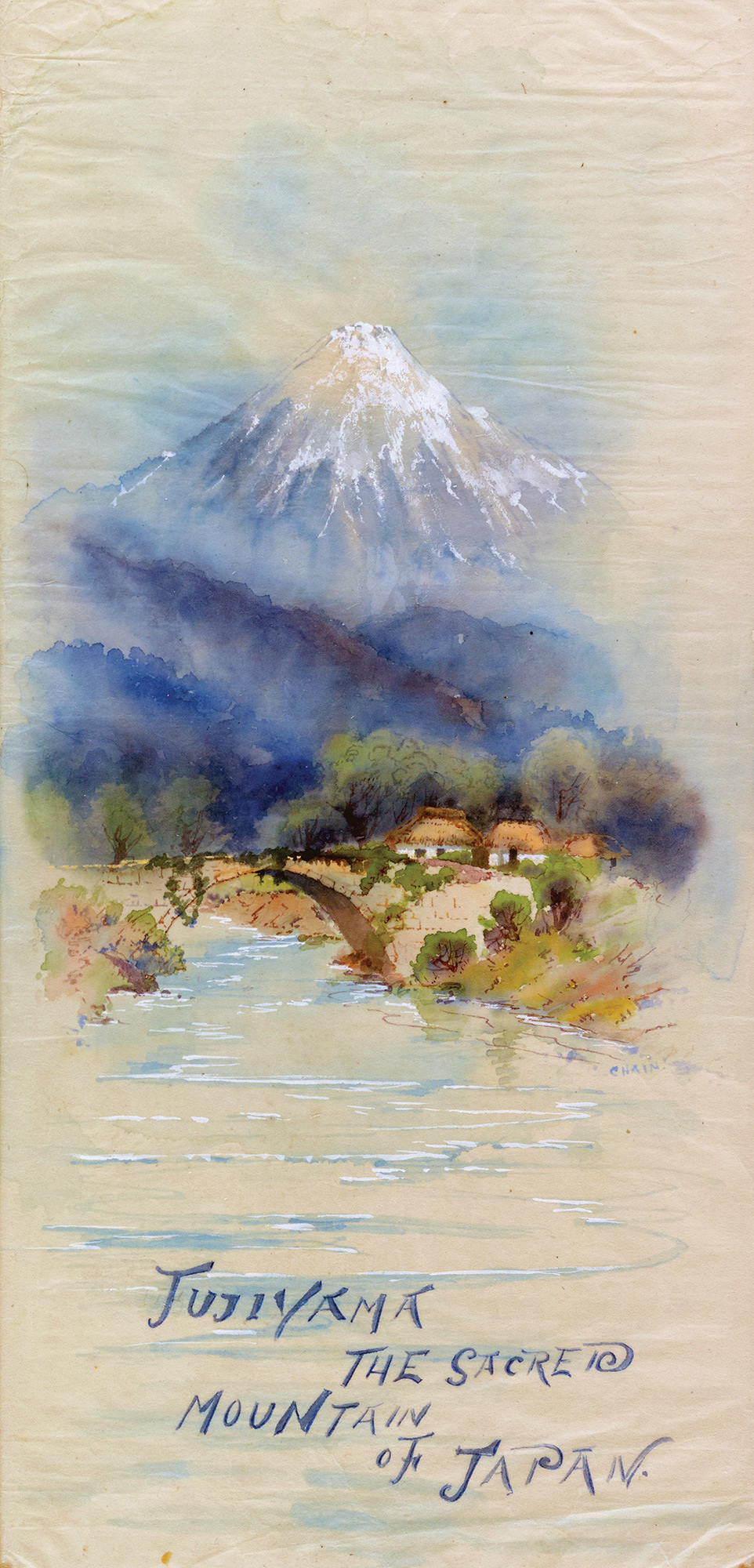

The artist’s lifelong fascination with Asia was probably one reason she and James first headed there when they set off on a two-year, around-the-world journey in March 1892. They spent several weeks in Japan, where Helen immersed herself in Japanese art and culture. While there, she produced a large Japanese-style scroll on which she discussed Japanese art history, illustrating it with watercolor paintings. A few months later, she mailed the scroll to the Denver Fortnightly Club, a scholarly group of cultured women of which she was a member. She intended for fellow members to read it aloud in her absence, sharing her admiring perspective on Japanese art.

After Japan, the Chains spent a number of weeks in China, planning next to travel to India. On October 8, 1892, they boarded the steamship Bokhara in Shanghai, headed for Hong Kong. Two days later, on October 10, the ship encountered a typhoon in the South China Sea. It sank and the Chains were drowned, along with almost 200 other passengers and crew. When news of the tragedy made it back to Denver, Fortnightly Club members and bookstore employees cut Helen’s scroll into pages and bound it as a massive volume, covered in Japanese silk.

Despite their early deaths, the Chains left a significant mark on the cultural life of early Denver. Helen’s advocacy for art was an important factor in the 1891 establishment of the all-woman Le Brun Art Club, which was succeeded (after her death) by the Denver Artists Club, which morphed into the organization that years later founded the Denver Art Museum.

“She was groundbreaking in terms of women artists and important because of her influence through teaching,” Wadsworth says. “And James must have been incredibly encouraging to her, which was also unusual at the time. Helen was not doing the proper lady Sunday painting thing — she was out there bushwhacking and painting on site. She had a personal vision of the time and place, and it enriches our vision.”

- Helen Henderson Chain, “Mount of the Holy Cross, Colorado” | Oil on Canvas | 46 x 29 inches | Collection of Dusty and Kathy Loo

- Helen Henderson Chain, “Royal Gorge on the Arkansas River, Colorado” | Oil on Canvas | 43 x 22 inches | 1890 400000065, H.293.1, History Colorado

- Helen Henderson Chain, “Mount Eolus” | Oil on Canvas | 19.5 x 29.5 inches | Collection of W. Bart Berger

- Helen Henderson Chain, “Mount Fuji, Japan” | Watercolor | 10 x 4 inches | 1892 | Denver Public Library

No Comments