01 Sep Perspective: Thomas Moran [1837-1926]

If ever an American artist has been linked with a particular place, Thomas Moran and his work in the Yellowstone region is the shining example. His field sketches, made while in the company of Ferdinand V. Hayden’s 1871 United States Geological Survey expedition, were shown to Congress and helped support the formation of the nation’s first national park. Wood engravings of Moran’s images were published in both scientific reports and popular periodicals of the day, educating a public hungry for information about the wild and wonderful place. His heroic 1872 panorama, Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, was purchased by the U.S. government, and became the first landscape painting to hang in the Capitol. Moran’s connection with the American West continued for many years, resulting in a spectacular body of work. Thus it might seem as if Western travel was the genesis of Moran’s career as an artist, as well providing his only subject matter. But this was definitively not the case. Moran had begun to enjoy success as an artist a decade before the admittedly pivotal trip to Yellowstone.

Born in England in 1837, Moran was brought to the United States in 1844, where the family settled in Philadelphia. His career began with an apprenticeship in 1853 to a wood engraving firm, but soon the self-taught artist was supporting himself by selling his first paintings. By the 1860s Moran was earning a good living with paintings, original lithographs and illustrations focusing on the landscapes he encountered in such varied places as rural Pennsylvania, the Roman campagna and the forest of Fontainebleau outside of Paris. Not only was Moran experiencing diverse landscapes — with variations of latitude and light, humidity and plant life, geographical and manmade features — he was also visiting galleries and museums in Philadelphia, Boston, London, Rome, Florence and Paris to study how the masters such as J.M.W. Turner and Claude Lorrain painted their worlds.

The opportunity to travel to Yellowstone in 1871 was an unexpected but enthusiastically accepted diversion from the direction Moran’s career was taking. The trip offered him the chance to experience a landscape few had seen and none had painted, subject matter that would occupy him throughout the rest of his life. It also provided a meteoric boost to his career. The 1870s brought intensive Western travel and work for Moran, with subsequent journeys to such places as Yosemite, the Grand Canyon of the Colorado and the Mountain of the Holy Cross.

As important as Western travel was to Moran’s career, it was not his only focus; during the later part of the decade and into the 1880s he engaged in significant other endeavors. In 1877 he visited Florida, which was just beginning to be explored by speculators and developers, to gather images that could be used to promote tourism as well as investment. After painting the arid West, Moran seemed to revel in depicting the lush tropical landscape of Florida. A trip through Mexico in 1883 for the Mexican National Railroad yielded a wealth of sketches and later paintings.

Moran’s great strength as an artist was to impart what is often referred to as a sense of place. Although his work clearly demonstrates a signature style — firmly grounded in topographical study and draftsmanship, and enhanced by exquisite brushwork and color — Moran was not content to impose a singular “look” to his work. He was masterful in his ability to capture in paint not just the geographical disparities that exist between the Rocky Mountains and coastal Florida, but more importantly and subtly, the distinctions in the quality of light and air.

While Moran could have spent his career doing nothing more than supplying the public’s neverending desire for paintings of Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon — certainly he painted and quickly sold many paintings of the American West throughout his career — his intellectual and artistic curiosity inspired Moran to exuberantly seek out new challenges. In the late 1870s the artist turned his attention back to creating fine art prints, a practice from which he had been sidetracked by his first trip to Yellowstone. After making his first etching in 1856, Moran tried his hand at various original print media throughout the 1860s. Particularly treasured today are his masterful stone lithographs of Lake Superior, the forests of Pennsylvania and the Bay of Naples.

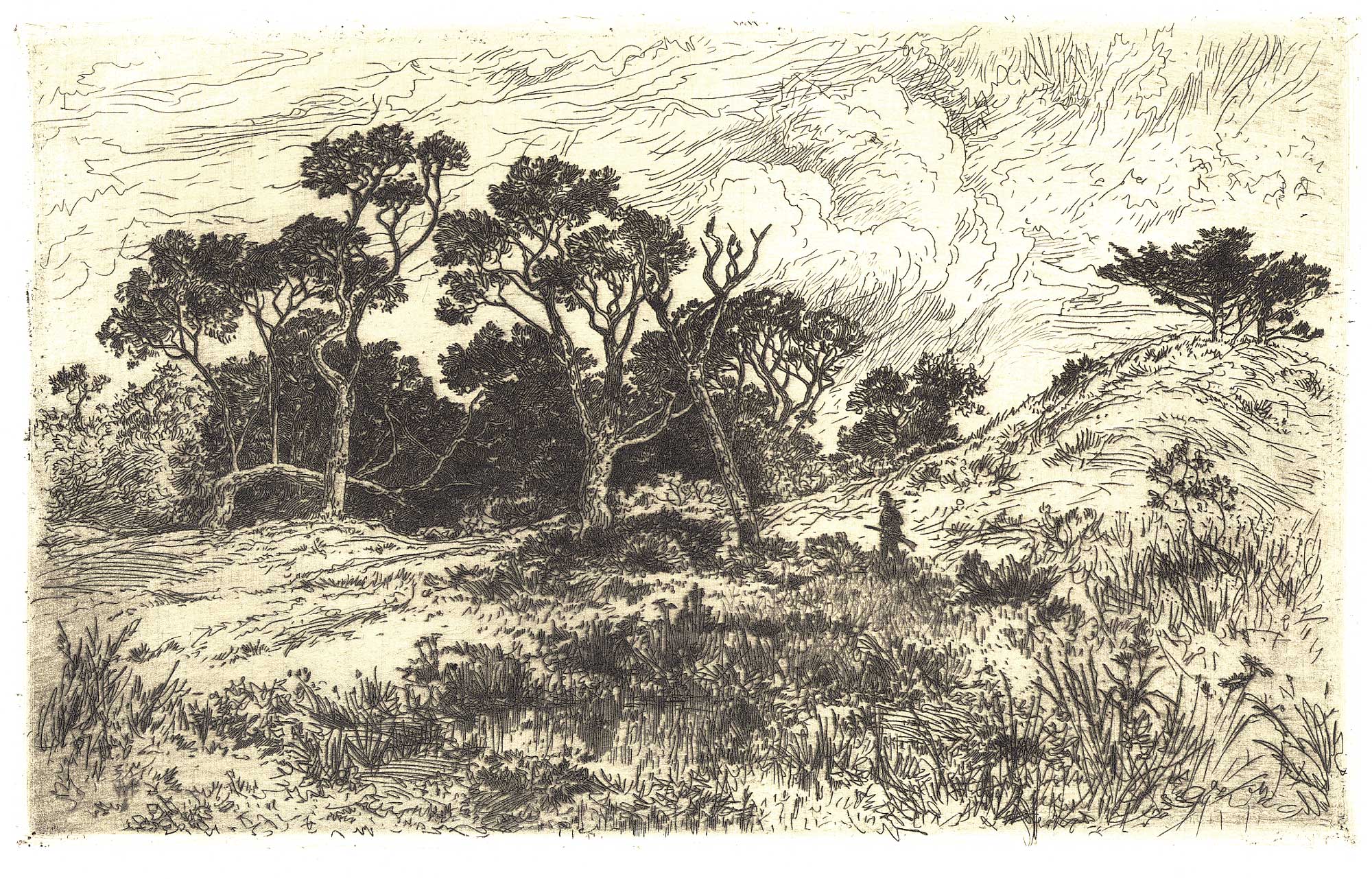

Returning to etching in 1878, Moran was a major proponent of the Painter-Etcher movement, which encouraged artists in American and Europe to create original prints. Though short-lived, the Painter-Etcher movement was a critical part of Moran’s artistic life, and one that he shared with his wife, Mary Nimmo Moran. They were founding members of the New York Etching Club. He made more than 70 etchings over the next 12 years, and she even more. Even though Moran came back to etching on the heels of his Western experience, fewer than 10 featured the West. Several, such as Tower Falls, capitalized on America’s continued interest in Yellowstone. More than half of his etched subjects were landscapes inspired by Eastern places such as the environs of East Hampton, New York. Moran and his wife had first visited the Long Island community in 1878, building a home and studio a few years later. The beautiful etchings, many of which are small and intimate, reflect the proximity to and affinity for the scenery Moran enjoyed daily. He also devoted much of his painting energy to the Long Island landscape, creating beautiful, richly green and complex studies that are sometimes overshadowed by other more dramatic subjects.

Over the next 40 years, until his death in 1926, Moran continued his quest for new subject matter, revisiting favorite places and experiencing new ones. One place that was particularly influential was Venice, Italy. To see Venice for himself had been a long-held dream, sustained through the paintings of artists he admired. His visit in 1886 did not disappoint him, and from that time forward, Venetian subjects were central to his work. During his lifetime, they sometimes rivaled his paintings of the American West in popularity.

Today, Thomas Moran’s Western paintings are the most sought after of his work, evidenced by last year’s stunning sale of Green River of Wyoming (1878) at Christie’s May 21, 2008 auction for $17.7 million. To date, this is the most paid at auction for any 19th-century American painting. While most of his Western works have sold in recent years for substantially less, they still continue to exceed the auction prices of his non-Western subjects.

For example, in the same Christie’s sale, Moran’s A Passing Shower in the Yellowstone Canyon (1903), a 16-by-20-inch oil, sold for $2,505,000. Also in the sale was another oil of the same size, Santa Barbara Mission (1916), selling for $205,000, less than 10 percent of the price of the Yellowstone painting. Although California is certainly in the West, the lovely pastoral scene is not one of the natural wonders. A few months later in Christie’s December 4th sale, another similarly sized Moran, East Hampton, New York (1919), did not sell, failing to attain its low estimate of $100,000 (less than 4 percent of the final sales price of the Yellowstone painting).

All three of these paintings are gorgeous examples of Moran’s mature work, and although these extreme examples do not take into consideration the adverse change in the economic situation in the United States between May and December of 2008, nevertheless in most cases non-Western subjects are not priced as highly. So, it seems that there is an opportunity for both the new and experienced collector to purchase work that is still affordable, by one of America’s most admired artists. Moran’s paintings of Long Island, Florida, Mexico, Venice and other non-Western scenes are, in many cases, strikingly beautiful portraits of places for which Moran showed a great personal appreciation.

On a much more modest level, owning an original Moran is well within the reach of most of us. Many of Moran’s etchings are available in the range of $250 to $3,500. Truly original works, all of these prints were hand-etched by Moran, and most were printed by him as well. His hand is obvious (and fingerprints in some cases!), as he manipulated the ink on the plate before printing. Side-by-side comparisons of two prints of the same plate reveal the unique character of each print. Although Moran did not produce limited editions (“editioning” of fine art prints did not come into vogue until the 20th century), due to the nature of the copper etching plates, usually fewer than 100 prints would be made from each plate before the etched lines began to degrade. A recent Google search disclosed a number of beautiful prints offered for sale, such as several Passaic Meadows (In the Newark Meadows), from 1879. Other etchings range from Moran’s hauntingly beautiful The Pass at Glencoe, Scotland to the heroic The Much Resounding Sea, both from 1886.

Thomas Moran was a remarkable and prolific artist whose talent is often only partially acknowledged for his work in the American West, when in fact, the importance of his career spans deeply into the tradition of American art.

Further Reading …

Thurman Wilkins’ definitive and engaging biography, Thomas Moran: Artist of the Mountains, first published in 1966, was revised and enlarged in 1998, by the University of Oklahoma Press. The exhibition catalogue, Thomas Moran, by Nancy Anderson, Yale University Press, 1997, includes essays by Anderson, Thomas Bruhn and Joni Kinsey on Moran’s career as well as a lengthy chronology of his life and work. Thomas Bruhn has written several books and essays on Moran and the importance of the Painter-Etcher movement, including the exhibition catalogue American Etching: The 1880s, Benton Museum, 1985. Moran paintings are routinely included in various annual auctions and are presented by fine art dealers around the country. His prints can be located through reputable print dealers, many of which are members of the International Fine Print Dealers Association (www.printdealers.com).

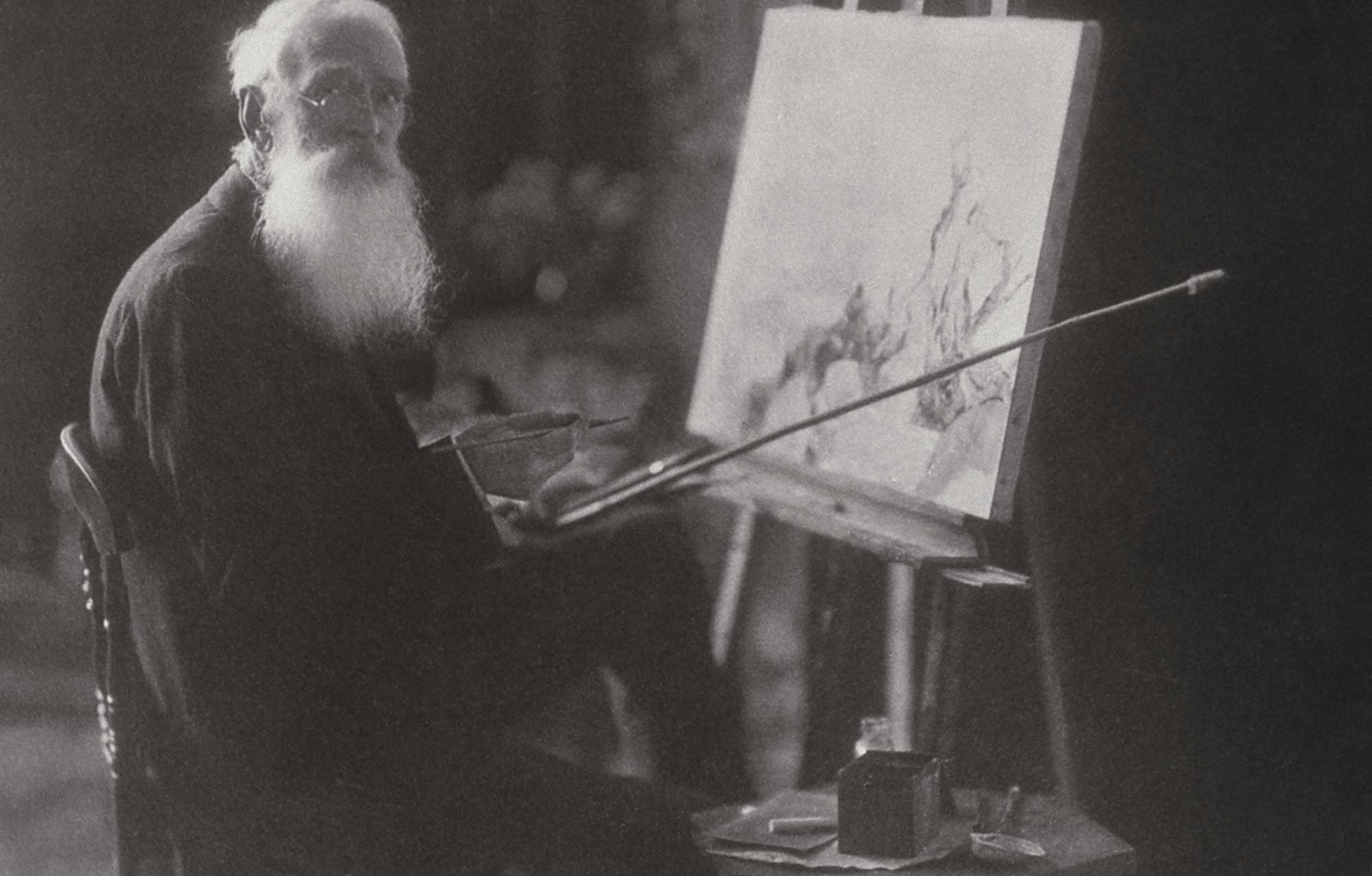

- Thomas Moran at easel, age 78 | circa 1915 | photographer unknown | NPS photo

- “A Passing Shower in the Yellowstone Canyon” | Oil on Canvas | 1903 | Courtesy Christie’s Images LTD 2009

- “Green River of Wyoming” | Oil on Canvas | 1878 | Courtesy Christie’s Images LTD 2009

- “Vera Cruz” | Oil on Canvas | Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

- “A Southerly Wind” | Thomas Moran |1880 | Etching | Courtesy Carter Saeteren

No Comments