30 May Perspective: Eanger Irving Couse [1866-1936]

“They were of the frontier, they witnessed its passing and they opened up the great future.”

— Dedicatory words for the New Mexico Art Museum, January, 1918.

One hundred years ago, Eanger Irving Couse bought an old adobe house on Kit Carson Road, in Taos, New Mexico. Who would imagine a house could reveal so much about an artist and his family, a society of artists and their friendship, indeed about the history and ambience of an era and a region? The art of that transformative period in the United States becomes more expansive when put in the context of lives lived and the expression of the human spirit in this home.

Couse had a burning desire to paint in an utterly original environment. In 1902, on the streets of New York, he discussed with friend and fellow artist Ernest Blumenschein a need to find fresh material and American Indian models who would pose. Upon the recommendation of Blumenschein, he indulged his wild imaginings and hopped the train to Denver, the spur south to Tres Piedras and then a buckboard wagon to Taos. Two weeks after his encounter in New York, he and his wife, Virginia, found in this New Mexico region an exotic native culture steeped in art, but barely touched by the brush. Taos was a small Spanish village near Taos Pueblo — the oldest continuously occupied community in America, established in the 13th century.

The summer of 1902 was the hottest ever recorded, which exacerbated the crude conditions: no running water or electricity, dusty streets, little law enforcement and limited supplies hauled by wagon over the mountainous terrain. But the Couses were hardy and had made other sacrifices in the name of art.

E. Irving Couse was born in Saginaw, Michigan, in 1866. As a young boy he sketched the local Chippewa tribe, showing an early affinity for art and an attraction to the American Indian. At 16, already clearly focused, he left home and enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago. After three months his summer wages were gone so he returned home to earn more money. The National Academy of Design in New York was his next destination. At 20 he joined the migration of American art students to Paris, the art capital of the western world at that time. Couse studied at the Académie Julian, where he developed his style and technique as a figure painter. His greatest influence, William Bouguereau, taught discipline and technique. This professor’s philosophy was reflected in his own journal entry:

… Think about the drawing, the color, the composition; don’t work without thinking equally about all these things, because nature, your only real master, has forgotten nothing.

Virginia Walker, a ranch girl from south central Washington, also traveled to Paris to study art. She and Couse fell in love and married two years later in 1889. Her letters home told of the primitive conditions of Paris where she was considered an oddity for bathing as frequently as once a week.

In 1893, they moved to Etaples, an art colony in Picardy where Couse painted fishing and pastoral scenes and peasant life. Three years later they returned to the United States and lived on the Walker Ranch in Washington.

Art critics complained that American art had lost its national identity under the French influence. Perhaps in response, Couse sought a truly American theme and painted the local Northwest Indian tribes. It was difficult to get models because the Indians were superstitious about having their likeness reproduced. So it was in 1902 on the streets of New York that he was introduced to Taos, a place that would become the focus of his art and life from that point forward. For professional purposes, he kept a winter studio apartment in New York until 1928.

Couse became a prominent artist early in the 20th century. Using the Tonalist style he developed in France, he received national acclaim for his dramatic moonlight and firelight depictions of the Pueblo Indians. Unlike some artists of the day who painted warlike images, he painted the proud, noble Indian in a peaceful pose. He won prestigious awards and was elected to membership in the National Academy of Design. Santa Fe Railway featured Couse paintings in its promotional calendar for more than 20 years, adding to his national exposure.

Couse was one of the founders of the Taos Society of Artists, along with Joseph Henry Sharp, Ernest Blumenschein, Bert Phillips, Oscar Berninghaus and Herbert (Buck) Dunton. As a group they were very organized, professional and boldly self-promotional. They organized an annual exhibition circuit that traveled to venues across the country and abroad. The shows left rave press reviews in their wake. As a result, the members gained legendary acclaim and national prominence, as did Taos and Southwest art. The Taos Society grew to 12 artists and stayed together 12 years. Association with the group gave each artist a permanent place in history.

Couse still had challenges with Pueblo models. They showed up unreliably and often came dressed in costume one day only to arrive the next in completely different attire. He tried to explain the importance of wearing the same clothes for the painting, but they had often sold their costume. Thus he bought and provided the outfits they would wear. Two of his favorite models were Jerry Mirabal (Elk Foot) and Ben Lujan. Mirabal, who was extremely handsome and also posed for J.H. Sharp, was feisty, but his attitude and arrogance gave him the proud dignified air the artists wished to paint. Ben Lujan began modeling for Couse at the age of 10 and continued into manhood. Lujan became like a member of the family, even referring to himself as Ben Couse Lujan.

Couse was widely considered a kind and gentle man, beloved by his family, friends and the Pueblo Indians. He was nicknamed “Green Mountain” by the Indians because he always wore a green cardigan over his rotund figure. Following his death on April 24, 1936, a description of his funeral by Lorraine Carr appeared in The Santa Fe New Mexican:

On April 24, 1936, E. Irving Couse passed on. We gathered in the beautiful garden to say good-bye. As the faithful Indians, dressed in bright colored shirts, beaded moccasins and yellow buckskin trousers, bore the body of the great artist from his studio, there seemed to hover over us a weird solemnity, an utter stillness, a closeness to God. Their devotion was further demonstrated by their walking beside the body, covering the entire distance from the studio to the cemetery on foot. Stoically they stood over the grave until the last of us had departed, then in their simple way they offered up prayers, not audibly, but in the devotional language of their hearts, imploring the Great Spirit to bear their beloved ‘Green Mountain’ on to the Happy Hunting Grounds.

On a quest for gaining access to J.H. Sharp’s studios in Taos, I found myself on the phone with Virginia Couse Leavitt, Couse’s granddaughter. Was it coincidence or a magical, fortuitous connection that historic friendships were reignited with our meeting? Mr. Sharp began to sell his property to Kibby, Couse’s son, in the 1930s, retaining a life estate. In a 1938 letter to Carolyn Reynolds Riebeth, my husband’s grandmother, Mr. Sharp wrote, “Have also sold our place in Taos to our neighbor, Couse (son of my artist friend).”

Pushing open the heavy wooden door to the adobe portal with the hand-carved letters, “Couse Studio,” there is a timeless feeling. Couse’s home is as it was all those years ago.

The Sharps and Couses were neighbors and good friends. Besides a passion for creating art, the two artists shared a common wall adjoining the Couse home and Sharp’s studio. They also ‘shared’ patrons. The tale goes that Sharp’s dog, Mr. Murphy, was trusted to give him a sign if a visitor was a potential customer. If the dog raised one ear, there was money; if he raised the other, they were not good prospects. John D. Rockefeller visited and the dog raised the wrong ear. Turned away, Rockefeller went next door and purchased several Couse paintings. Couse never let Sharp live it down.

Two J.H. Sharp studios remain part of the Couse property. After touring them, my husband, the great grandson of Sharp’s dear friends, the S.G. Reynolds and Couse’s granddaughter, Virginia, sat on the portal where the Taos artists had gathered to visit on balmy summer evenings; where they showed each other paintings, discussed the business of art and marketing and staged impromptu performances for entertainment. We had the good fortune to hear their story from Virginia Couse, the lovely lady and historian who, as a child, called J.H. Sharp ‘Uncle Henry’ and Ernest Blumenschein ‘Uncle Blumy.’

The Couse/Sharp Historic Site has become a shrine to art and friendship. The Couse family has been so aware of the historic significance of the property and so fastidious in the process to preserve it, that the home, grounds, furnishings and the artistic accoutrements are pretty much as they were. Couse’s studio looks as though he just stepped away for a bit from his easel, chair and brushes. In his house its furnishings, collections and archival documents are preserved, including 8,000 negatives and prints. Virginia’s husband, Ernest Leavitt, a museum curator, has provided valuable expertise into the preservation of the property.

In a house where there is a perceptible aura of art, and hospitality has reigned for 100 years, we ate an amazing dinner around the same table at which the Taos Society artists dined with the same creaking rawhide lampshade overhead. Mrs. Couse had been a wonderful hostess and her granddaughter, Virginia, carries on the tradition today. In the glowing candlelight around the cleared dining table, Virginia read a lively letter her grandmother had written to friends back East telling vivid accounts of adventures in the untamed region of Taos. The past blurred and Virginia Couse came to life through the written words of her quiet, refined, intelligent namesake. The sparkle in her eye came, quite possibly, from her grandfather, E. Irving Couse.

Editor’s Note: Celebrating the centennial of the purchase of the Couse/Sharp Historic Site, the exhibit Kindred Spirits and the Adobe Connections: E.I. Couse and J.H. Sharp will be on display from June 19 – October 18, 2009 at the Harwood Museum, www.HarwoodMuseum.org/events.

Montana-based writer Carleen Milburn is a frequent contributor of travel and art features. She writes for numerous publications, including, Art of the West, Big Sky Journal, Fine Art Connoisseur and Montana Living.

Amy Archer has a favorite story about her grandmother traveling to Taos as a child to visit family friend Henry Sharp. At his home, Mr. Sharp invited the young girl to choose a favorite painting to take home, her own “postcard from Taos.” As a photographer shooting art and travel stories across the West, Archer enjoyed retracing her grandmother’s long-ago journey.

- E.I. Couse’s palette and brushes

- E. I. Couse, corner of his studio at the Walker Ranch, Washington, c. 1896, oil on canvas.

- View of J.H. Sharp’s “Studio of the Copper Bell” and his house, c. 1920.

- Pueblo Indian pottery on the Couse fireplace,

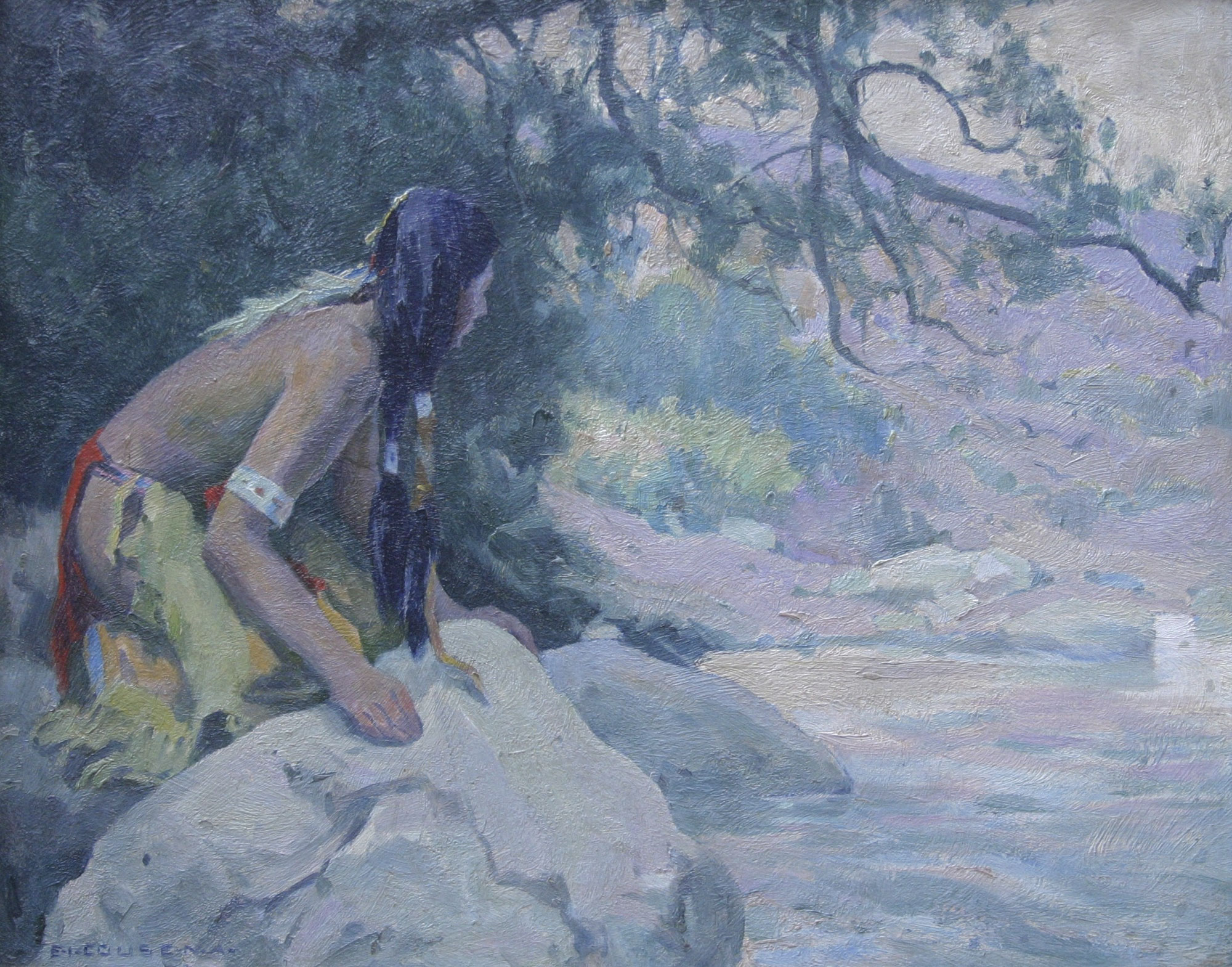

- E. I. Couse, “Afternoon on the Rio Grande”, 1923, oil on canvas.

- Society of Taos Artists. Top L-R, Walter Ufer, W. Herbert Dunton, Victor Higgins, Kenneth Adams; middle, E. Martin Hennings, Bert G. Phillips, E. Irving Couse, Oscar E. Berninghaus; lower, Joseph Henry Sharp, Ernest L. Blumenschein c. 1927.

- The easel in the corner of Couse’s studio and the unfinished canvas is just as it was a century earlier.

- “Moonlight” Eanger Irving Couse, (1866-1936) | Oil on Board | 9 x 12 inches

- Couse studio, 1909. (Painting on right, Elk Foot of the Taos Tribe, now in the collection of the American Art Museum, Washington, D. C.)

- E. I. Couse, “Portrait of Virginia Walker Couse”, Paris 1980, oil on canvas.

- Virginia Couse Leavitt, E.I. Couse’s granddaughter.

_-Moonlight_-oil-on-board_-9-x-12-inches_-High.jpg)

No Comments