30 May Perspective: Maynard Dixon [1875-1946]

Lafayette Maynard Dixon always claimed that he had little interest in fabricating visual fiction. For him, his Native American West had been needlessly over-romanticized by Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Moran and George Inness. They had been mere interlopers with brushes and tourist visas in hand.

“Painting, as I see it, must be human rather than arty,” Dixon once said. “Painting is a means to an end. It is my way of saying what I want you to comprehend. It is my testimony in regard to life, and therefore I cannot lie in paint.”

The ‘truth,’ as known to Dixon, remains a larger-than-life dreamscape, girded by stark geometric landforms; surreal tracts of cumulous sky; diaphanous atmospherics; and common, ungaudified Indians, gauchos and migrants who haunt our collective imagination in ways that seem more relevant than ever.

During Dixon’s long association with the Southwest, he adopted the mystical thunderbird as an artistic fetish, though more than 60 years after his death and amid unprecedented public interest in his work, a more suitable avian talisman might be the phoenix.

Today, in a time of war, economic hardship, environmental degradation and loss of open space, the cult of Maynard Dixon is enjoying a resurrection.

Across the country, his realistic portrayals of nature and the human condition have sold for record prices at auction. A traveling exhibition of the artist’s work, launched by noted Dixon collector Abe Hays, is currently enjoying a second run as it barnstorms to large crowds in a half-dozen museums. And every summer, near the sagebrush meadow where Dixon’s ashes were scattered in Mt. Carmel, Utah, and where his third wife, Edith Hamlin, affixed a thunderbird plaque to their log-and-stone studio, artists converge in remembrance.

Ironically, the same stylistic peculiarities that once rendered Dixon an obscure presence in the eyes of the Western fine-art establishment are now propelling him forward into a new era of critical appreciation.

As you read these words, a debate as superheated as the Mojave sands in August swirls around the question of whether “Dixon mania” represents the coronation of Dixon’s posthumous arrival in the canon of American masters or is merely the reflection of a euphoric art market.

“There is this incredible, overwhelming interest in Dixon and it has tipped to a new level. I don’t see anything stopping it in the near future,” says Dr. Mark Sublette, owner of Medicine Man Galleries in Tucson and Santa Fe, and an expert on the artist. Medicine Man specializes in Dixon and, in addition to having sold more than 300 original paintings by the artist, it operates the Maynard Dixon Museum in Tucson that features Dixon’s paintings, poetry and writing.

Sublette notes that Dixon’s popularity has fueled the emergence of fakes on the market and being sold on the Internet. A way to guard against it is to check the work against the Dixon Catalog Raisonné being compiled by noted Dixon authority Donald J. Hagerty.

“Suddenly, everybody loves Maynard Dixon, but it wasn’t always that way. Personally, I have long regarded him as the number one painter of the inner West between 1900 and 1950,” says Vern G. Swanson, director of the Springville Museum of Art in Utah. “There have been other great painters, of course, including the Californians like Edgar Payne and the Taos painters like [Ernest] Blumenschein, but what Dixon brought was an original and exceedingly powerful aesthetic.”

A native of Fresno, California, Dixon was born in 1875 and died an iconoclast in 1946. A reluctant magazine and book illustrator in San Francisco, he achieved national name recognition early. But even in his twenties and thirties, having landed a stint with Harper’s in New York, he felt burned out on the human rat race. He also had to contend with an Eastern view of the West, as forged by Bierstadt, Moran and others, that did not comport with his own.

He never forgot the fate-altering counsel he received from famous journalist, poet and Indian-rights activist Charles Fletcher Lummis. As a man who himself had eccentrically walked 3,500 miles from Ohio to take a newspaper job in Los Angeles in 1884, Lummis told a young Dixon that he needed to travel eastward from California out into the desert in order to encounter the essence of the true West. In a fatherly letter, as relevant to young artists today as it was at the turn of the 19th century, he advised Dixon: “Do your damnedest. So live that you can look every damn man in the eye and tell him to go to hell. Sell drawings, but don’t sell yourself.”

On one of his first major forays into the desert, Dixon was joined by painter Edward Borein. Abe Hays, a Dixon authority and co-owner of Arizona West Galleries in Scottsdale, adds that while Dixon set out down his own solitary path, he was always eager to accept mentorship from people he respected. “[Frederic] Remington wrote him a page and passed along some valuable advice. He said that among the most important rituals a good painter must have is to draw, draw, draw; every day, and always from nature,” said Hays. “That’s what Dixon did. The strength of his draftsmanship, the thousands of drawings he made, provided the architecture for his painting.”

Dixon emerged from a firmament of avant-garde ideas bombarding visual artists at the dawn of the 20th century. The period was punctuated by the legendary Armory Show in New York City in 1913 that hosted the first international exhibition on modern art, and the arrival of the 1915 World’s Fair in San Francisco that deposited a whole new set of isms on the West, shoving the romantics aside.

Point of fact, Dixon eschewed the urban pretension emanating from New York and California, preferring to paint the way he wanted in geographical isolation. Some have described him as evolving into abstraction, cubism and modernism, but he never saw himself as a conscious adherent of any formal movement. He borrowed from all three in his paintings and murals, even acknowledging what his European contemporary, Picasso, was doing.

Swanson says it is correct to assert that Dixon’s paring down of visual detail represents a tip of his hat to modernism, but his affinity for the rural countryside, not the city, clearly demonstrates a reverence for the natural over the man-made universe.

“Modernism has three primary features: It is anti-beauty, anti-craft and anti-art,” Swanson says. “Nothing about Dixon’s philosophy accorded completely to the modernist paradigm. When I think about him, I see a 20th-century version of the Renaissance painters. He was very interested in clouded, atmospheric light and perspective. He told you everything you had to know about a scene. He gave you the scientific elements, his rationale for being there and the art-related explicatives that make his painting uniquely his own. Not lost in any of it was heart.”

“Dixon … like few I have known, appreciated the whole of the land, as well as its parts and their interrelationships. For him, the West was uncrowded, unlittered, unorganized and above all, vital and free,” observed his friend, the photographer Ansel Adams.

Where Dixon felt most grounded was in the Navajo sandstone labyrinths and cactus-covered mesas and ancient Dine passages, like those in Canyon de Chelly. At one point in 1917, when he was feeling disillusioned, Dixon fled to Montana and spent time afield with Charles M. Russell at Lake McDonald Lodge in Glacier National Park near the Blackfeet Indian Reservation. Soon, though, he drifted south again.

“The desert is a special place and to know it you must sleep in it, and awake in it, and dream in it,” Hays says. “The time that Dixon spent among Indians in New Mexico, Arizona and Utah charted the future of his life and career. He discovered that Indians don’t talk about the desert; they think about it and their visual response is part of an unspoken meditation. Similarly, good artists are contemplating all the time, seeing from an intellectual and serious perspective that the rest of us don’t have.”

Dixon’s style speaks as much to his own internal landscape as to his visceral conveyance of dry, shadowy light. “On the psychic level, you look at a Dixon painting and even if you’ve never been to the Southwest you feel it become part of you. Dixon is the West,” says Anne Morand, director of the C.M. Russell Museum in Great Falls, Montana. “He did not paint scenes literally in front of him. There was something much bigger going on.”

Dixon delighted in exploring the volume of chasms existing between Western foregrounds and backdrops, manipulating what he called “space division” to achieve mesmerizing effects with geometric lines and planes of color and form.

Landscape painter Scott Christensen, a winner of the prestigious Prix de West competition hosted each year by the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, has studied many of Dixon’s painting venues.

“Force of line, harmony of color and composition are always the first things that come to mind when I think of Dixon,” Christensen says. “He didn’t try to say something with extreme statements that cried out, ‘Look at how much of a virtuoso I am!’ It was never about trying to duplicate what the market calls ‘pretty’. His instincts were elemental.”

As Dixon’s vision matured, he indulged profusely in palette earth tones, but even at his most exuberant, his color is relatively subdued. He did not want to stand accused of being emotionally overwrought but he could not, as a person, suppress his empathy for the underdogs of humankind.

Together with his second wife, photographer Dorothea Lange, Dixon served as a witness to enormous human suffering, documenting migrant workers and Steinbeckian economic refugees. “If you examine his Depression-era figures, you see hobos and tramps presented with a certain sense of realistic social romanticism and an aesthetic that seems drawn out of modernism,” Swanson says.

The changing West, the ravages of the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906, the trauma inflicted upon people during the First World War, the miseries of the Great Depression and his own failed relationships all weighed heavily on Dixon. According to Desert Dreams: The Art and Life of Maynard Dixon, an excellent biography written by Donald Hagerty, Dixon confessed that “the Depression woke me up to the fact that I had a part in all this, as an artist.” His work needed to speak to his own time and not exist solely apart from humanity. He created two series of works devoted to hard luck Americans out of work and another of striking ship workers down at the San Francisco docks. They are a cross between Norman Rockwell and Edward Hopper.

Foremost, Dixon’s heart ached over the mistreatment of native people. To escape despair, Dixon still sought relief in nature. “I do not paint Indians or cowboys merely because they are picturesque subjects,” he said, adding that his aim was “to bring out the poetic, rather than the harsh, brutal part of their lives, or merely the wild and woolly. The supernatural in the life of the Indian interests me greatly.”

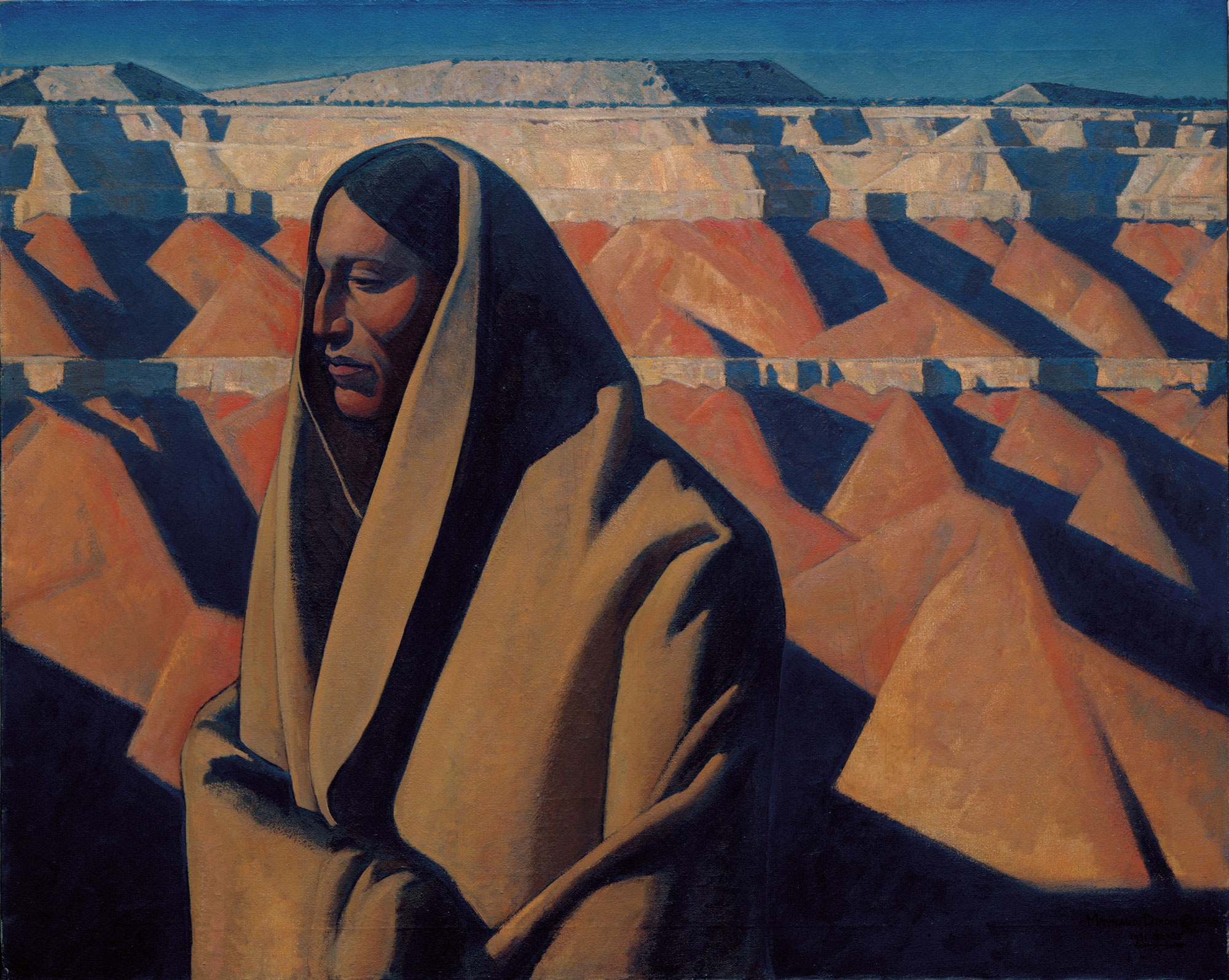

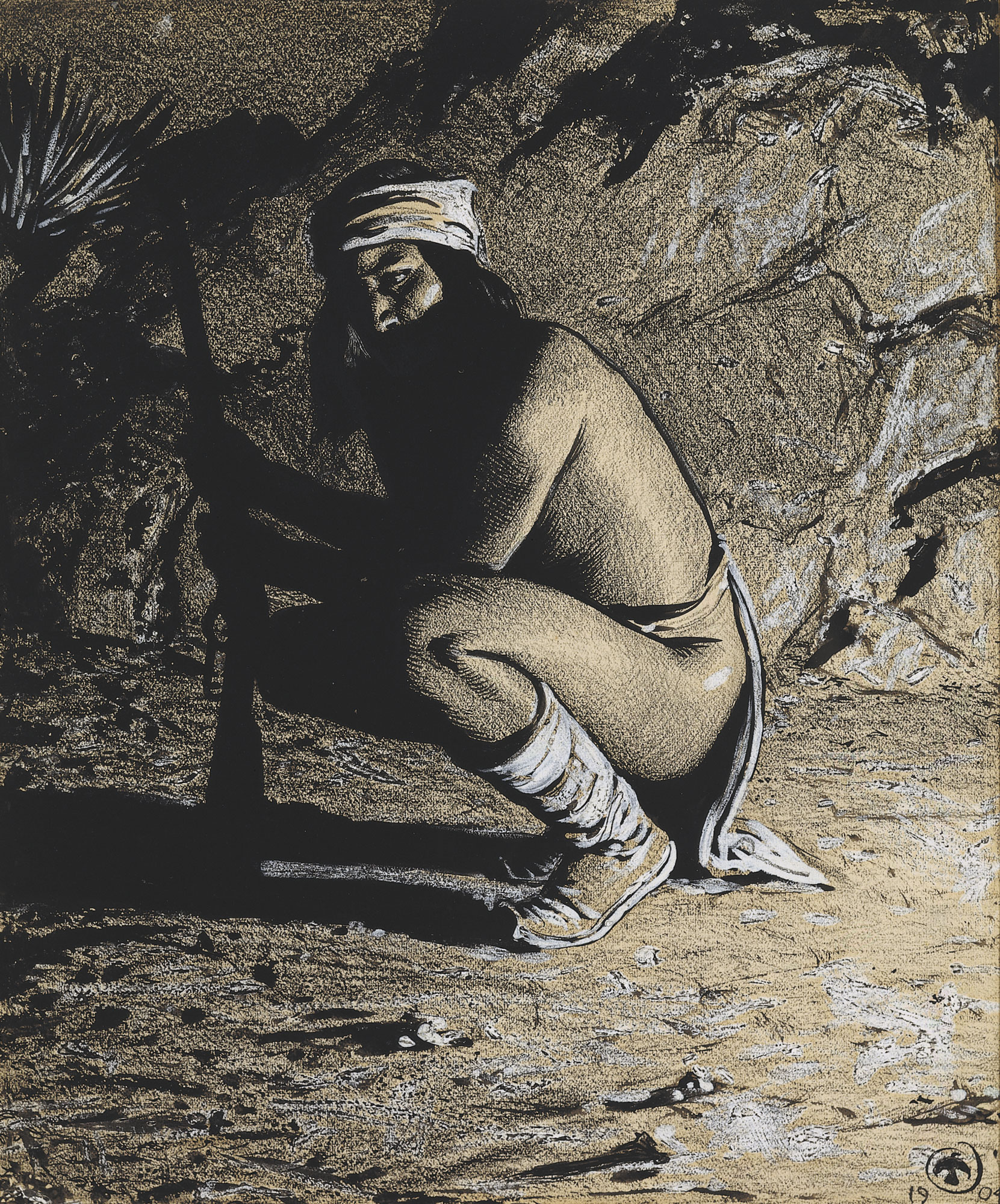

Among the Dixon masterpieces of that realm are Men of the Red Earth, Cloud World and The Earth Knower, which features a robed woman fronting a cubist red-rock canyon.

Dixon, too, was a poet in his own right. And the thunderbird, that being of lightning and rumbling sky, power and destruction, represented the clash between nature and technology.

Dixon has been dubbed “the peoples’ painter,” but the fact is for decades “the people” hated Maynard Dixon’s art, Swanson says. “They found it ugly. They said it looked as if it had been done by a kid. Clearly, it comes from the mind of a genius but the average person didn’t appreciate him and therefore he remained a bit of a secret to everyone but the connoisseurs. It’s worth noting that he had his greatest following among fellow artists.”

Adds Hays, “My feeling is that for years dealers in the West ignored him because they didn’t understand him.”

At Mt. Carmel, a backdoor gateway community to Zion National Park, he spent his summers in midlife dwelling amongst pious, straight-laced members of the Mormon faith, and then wintered in Tucson. Though as Swanson points out, “Dixon was anything but Mormon.” A chain-smoking curmudgeon, he was thrice married, could be rough in demeanor and was an intense intellectual who did not suffer fools. Nonetheless, his Mormon neighbors loved him. “He brought greatness to Utah and Utahans responded,” Swanson says. One of the largest public collections of his work, in fact, resides at the art museum at Brigham Young University.

As an art historian, Swanson has tracked “the flow of oeuvre” in more than 5,000 painters going back centuries. “Usually you see a malaise that starts in artists around age 60,” he says. “Some call it ‘old man’s pigment,’ but Dixon never had it. He kept his art at a vital level longer than we would have supposed possible, given the condition of his health.”

In the years leading up to his end, Dixon was saddled to an oxygen tank, battling emphysema and asthma caused by his smoking. In addition, he had arthritis. He continued to regularly sketch, however, and when he struck the canvas, he wielded his brush with assuredness, producing, remarkably, some of the best works of his career. One is the oil on canvas Open Range, painted in 1943. Another is Home of the Desert Rat, completed during 1944 and 1945.

When finally he succumbed in 1946 in Tucson, it is in Dixon’s own words that an epitaph can be found. His ashes, like the mythological phoenix, were brought back to his studio in Mt. Carmel, cast to the wind above the banks of the Virgin River, at a spot marked today with the image of a thunderbird that had become his enduring insignia on finished easel paintings.

“As often before, I went again to the desert to find an answer — and it was not far to seek,” Dixon had said. “I must find in the visible world the forms, the colors, the relationships that for me are the most true of it, and find a way to state them clearly so that the painting may pass on something of my vision.”

Exhibitions & Resources —Essential for Your Dixon Journey

Abe Hays, owner of Arizona West Galleries in Scottsdale, and his wife, own 68 original Dixons. This collection includes some two-dozen paintings, as well as 40 drawings, etchings and illustrated letters. In 2002, Hays sent his collection on a national tour that reached nine museums. Following a break, the works are traveling again on a tour that includes the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, the Rockwell in Corning, New York, the Booth in Cartersville, Georgia and soon, the C.M Russell in Great Falls.

The Tucson Art Museum also is hosting its own special Maynard Dixon exhibit from October, 2008, through February, 2009. The exhibit will house more than 100 Dixon works.

A fine full-length documentary, titled Maynard Dixon: Art and Spirit, and narrated by Diane Keaton, can be found at: www.maynarddixondoc.com. In addition, other websites worth visiting are the home of the Thunderbird Foundation, sponsor of the annual Maynard Dixon Country gathering in Utah, www.thunderbirdfoundation.com; and www.maynarddixon.org, operated in conjunction with the Sublette Galleries.

Finally, the most authoritative Dixon biographies are those written by Donald J. Hagerty, author (along with Dixon’s son, John Dixon) of Desert Dreams: The Art and Life of Maynard Dixon, and Mesas, Mountains and Man: The Western Vision of Maynard Dixon. Also well worth exploring are: Escape to Reality: The Western World of Maynard Dixon, by Linda Jones Gibbs, and The Thunderbird Remembered: Maynard Dixon, the Man and the Artist, by Dorothea Lange, John Dixon and John P. Langellier.

Todd Wilkinson, who lives in Bozeman, Montana, has written about art for three decades. When he isn’t interviewing artists, he is usually writing about the environment for national magazines and newspapers. Currently, he is at work on an authorized book about media mogul and bison rancher Ted Turner.

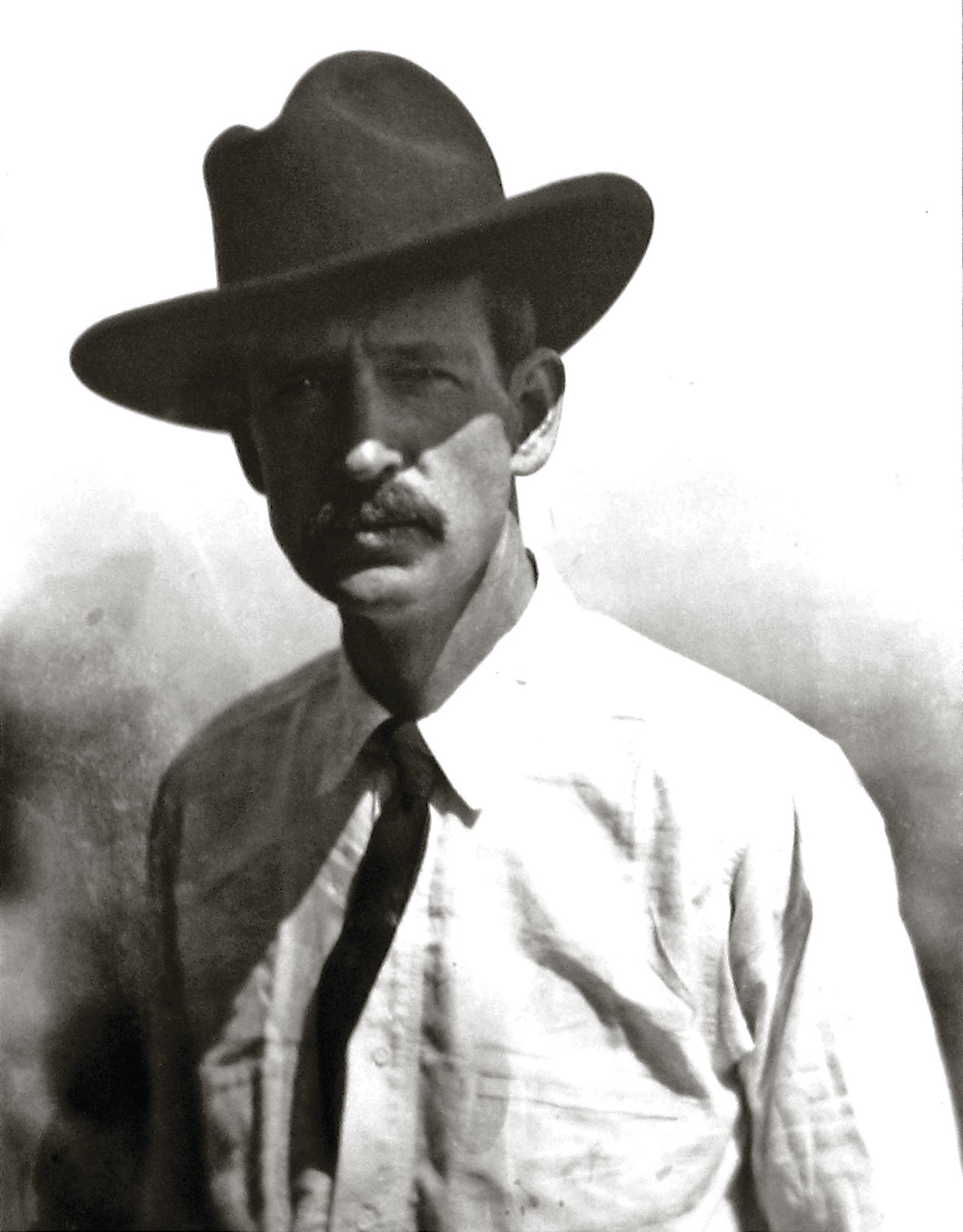

- Maynard Dixon, circa 1931, by Dorothea Lange.

- Maynard Dixon home, Mount Carmel, Utah. Images courtesy Thunderbird Foundation for the Arts.

- “Earth Knower” | Oil on Canvas, 1935 | 40 x 50 inches | Courtesy of the Oakland Museum of California

- “Home of the Desert Rat” | Oil on Canvas | 1944-1945 | Phoenix Art Museum, Arizona | Bequest of Leon H. Woolsey | The Bridgeman Art Library

- “Men of the Red Earth” | Oil on Canvas | 36 x 41 inches | Gift of Class of Summer, 1944, courtesy of the LAUSD Collection

- “Walls of Walpi” | 1923 | Oil on Canvas, 16 x 20 inches | A.P. Hays Collection

- “The Apache” | 1904 | Mixed Media, 12.5 x 10 inches | A.P. Hays Collection

No Comments