01 Feb Connectivity

MORE THAN 50,000 VISITORS WORLDWIDE are expected to view the work of 100 artists — 30 percent of whom create in traditional and non-traditional Western styles — at the annual Celebration of Fine Art (CFA), this year from January well into March.

Colorado’s James Ayers will bring his well-researched oil paintings of American Indian cultures to the 24th annual arts event. Mixed media and ceramic artist Vicki Grant of North Carolina will unveil sculptural and wall clays, and Arizona resident Curt Mattson’s lifetime passion for the horse and the cowboy will also be displayed in recent sculptures, drawings, watercolors and oils. Landscapes, including the Grand Canyon, mountain vistas and Western wildlife are among Kirk Randle’s recent subjects, and Michael Jones’ hand-forged ironworks will include tables, gates, fireplace screens and sculpture.

Part gallery, part working studio and part juried art show, the event showcases art beneath 40,000 square feet of signature white tents. Outside is a 1-acre landscaped sculpture garden. Open daily 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., the event is fully accessible for the physically challenged.

“Our mission is to provide an unmatched opportunity for artists and collectors to connect on a personal level which encourages creativity and interaction and, of course, the highest level of sales success for the artists,” says Susan Morrow Potje, who, with husband Jake, oversees the event. A dedicated city ordinance — the only one of its kind — accommodates the event’s 10-week run and underlines its importance for the Scottsdale community.

Susan’s father, Tom Morrow was an advertising executive who, along with wife, Ann, owned and operated galleries in the West. After being inspired by the Laguna Beach Festival of Art in California, they founded the CFA. Ann was also the executive director of Scottsdale Artists’ School in the late ’80s and early ’90s.

A major dynamic is its variety of styles and mediums, with bronzes and ceramics, furniture, figurative and representational paintings of artifacts, such as paintings of beaded moccasins and weavings. What’s more, offerings are continually changing as artists create in studios beside their galleries, Potje explains.

“When you walk through the tent, it’s like entering another world,” says regular visitor and art collector, Frank Racioppo of Incline Village, Nevada, and Fountain Hills, Arizona, a few miles east of Scottsdale. “It just lifts your spirits to see so much creativity and energy.”

Created in his High Plains studio at Elizabeth, Colorado, the six major new works Ayers is showing in Scottsdale include Rocky Mountain scenes of the Ute and Lakota, and desert vistas of the Apache. As with all of his work, these represent years of historical research combined with real-world experiences, camera at hand, of the depicted landscapes and peoples.

In fact, Ayers notes, much of his inspiration comes from his study of artists outside the Western art genre, research of artifacts and history, and travels to Native American communities. He is meticulous in recreating, for instance, the style of a man’s plaited hair, the weapons and the motifs that decorate tipis, clothing and shields.

Ayers has had several Native American mentors who have been willing to share perspectives on their respective cultures. “Because of these experiences, I have a mandate to respect the cultures I represent and to never trivialize real people or turn them into a cliché,” says Ayers, a Rhode Island School of Design graduate. Like Ayers, Mattson creates from his sinews, his heart and the seat of his pants, aspiring for accuracy and authenticity in celebrating the vaquero, buckaroo, ranchero and cowboy.

Combining the traditions of Edward Borein, Solon Borglum, Charles Russell and narrative Realism, the Glendale, Arizona, artist has three loves. “My life consists of the two most important things in my life — right behind my wife, Wendy, that is — horses and art. Few of us will ever know what it is like to be on horseback in country that swallows you up with its grandeur,” says Mattson, who grew up in the horse business in California, where his grandfather made saddles, bits and spurs.

Fluency in multiple mediums creates artistic eloquence.

“It expands the number of people you can communicate to,” he says. “The mediums inform and improve each other, so your work becomes more evocative.”

And, by working in diverse forms, he can help preserve the world he has been so intimately connected with from birth and has been artistically re-enacting for 30 years. “I’m all for anything that will bring people into the richness of the Western art world.”

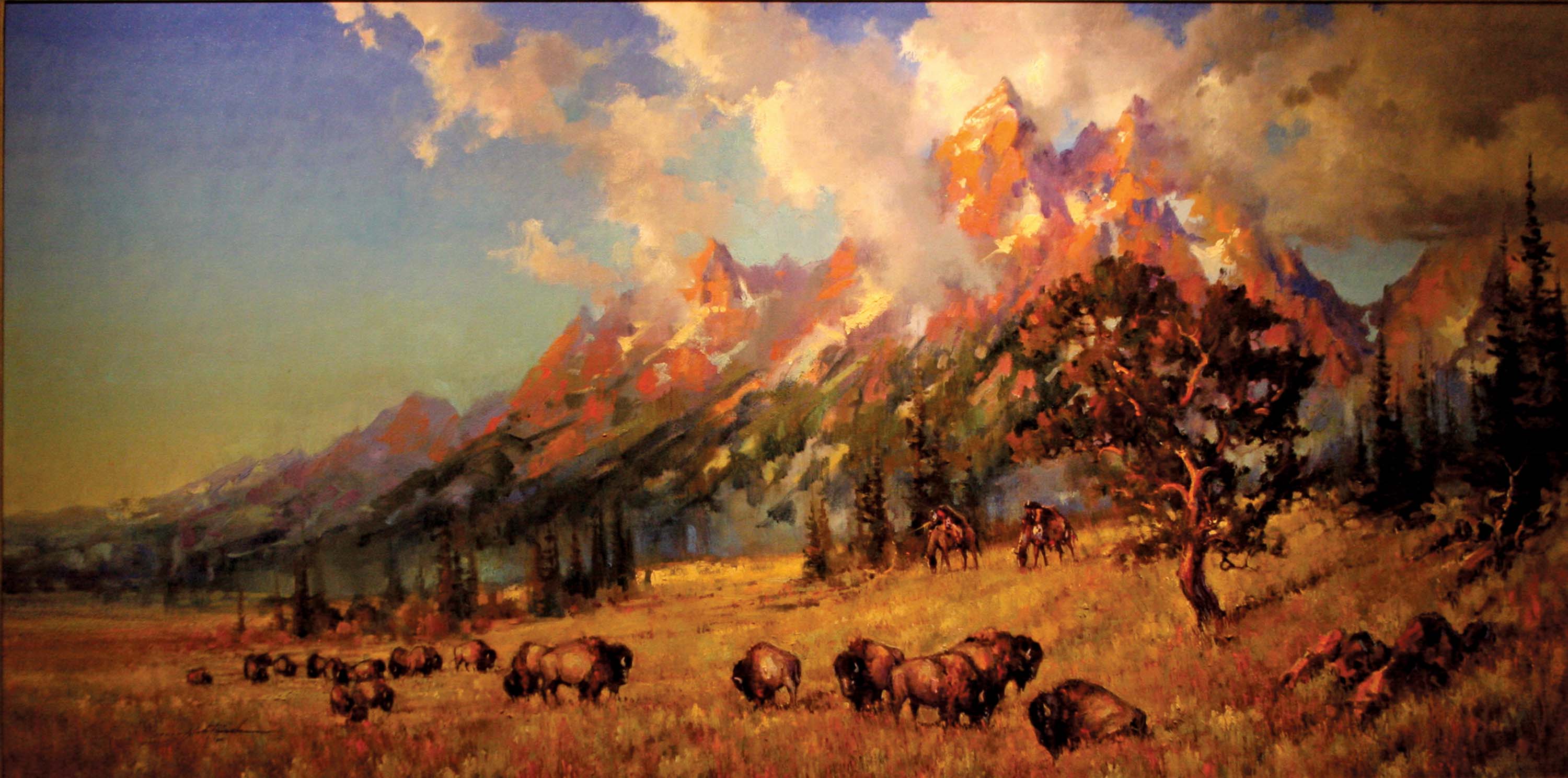

Working from his studio and home in Bountiful, Utah, Kirk Randle focuses on the Western landscape: vistas, wild-life in situ and Native American vignettes.

“Many of my renderings are a combination of reflection on the past played against images of present-day reality,” says Randle, who was influenced by his artistic mother and grandmother. “I may try to capture a sense of place or a moment in time in many of my paintings. I paint more from a sense of feeling than from an immediate response to an object or scene.”

In high school, Randle realized his passion for art and was offered a presidential scholarship to the University of Utah, enabling him to study and work at art full time. His teachers helped him, as have many professional artists.

He has attended all of the Scottsdale fine art shows. “It provides me with an environment in which I have a studio where I can paint, but also a gallery setting where I can interact with my clients. I have developed many enduring relationships which I cherish,” he says.

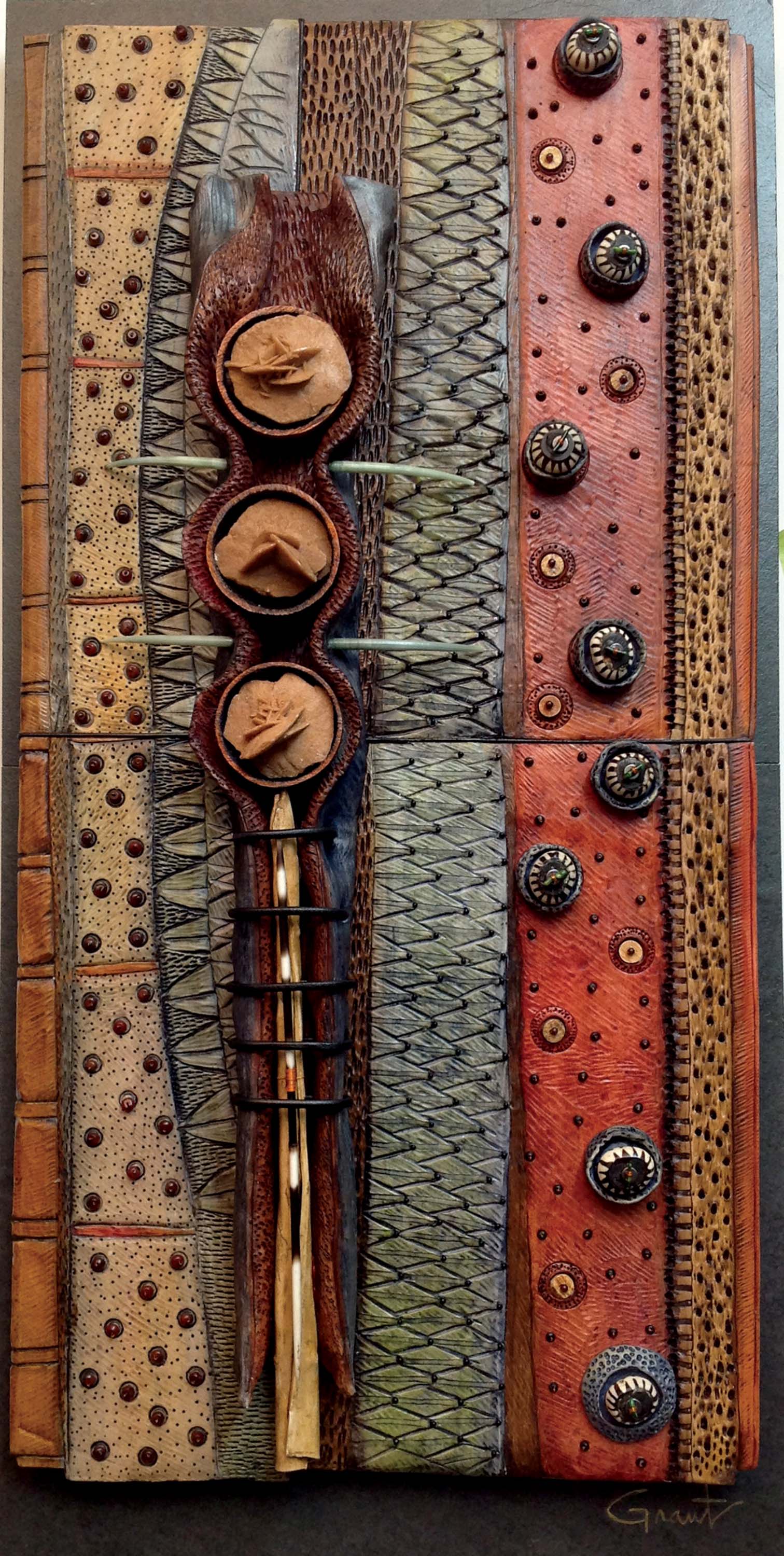

The evolving diversity of Western art has expanded the market in Scottsdale and elsewhere, creating a new kind of collector, Michael Jones says. “Though the styles differ, there are elements they have in common that define them as ‘Western.’ Those elements could be described as ‘connection’ — connection to place, connection to heart, a kind of grounded sensibility and passion for life.” He’s proud to work in the old blacksmith tradition, with dirty callused hands, smudged face and, on occasion, sliver-nicked arms. “All my work is done by hand, a craft that is hard to find these days. There are no machines, plasmas, lasers, water jets involved. Just an oxyacetylene torch and lots of grinding, hammering and polishing, bringing out the life and energy that is inherent in the steel. I believe it is this extra effort that defines my style.”

The works by prehistoric artists and their symbolism inspire his contemporary handcrafted art. A 25-year member of the Montana Archeological Society, he’s worked with many archeologists. “It’s so exciting to share our passion for the past and how it helps define our present,” says Jones, who since 1978 has lived with wife, Karen, and worked from a 120-year- old log homestead in northwest Montana’s Swan Valley.

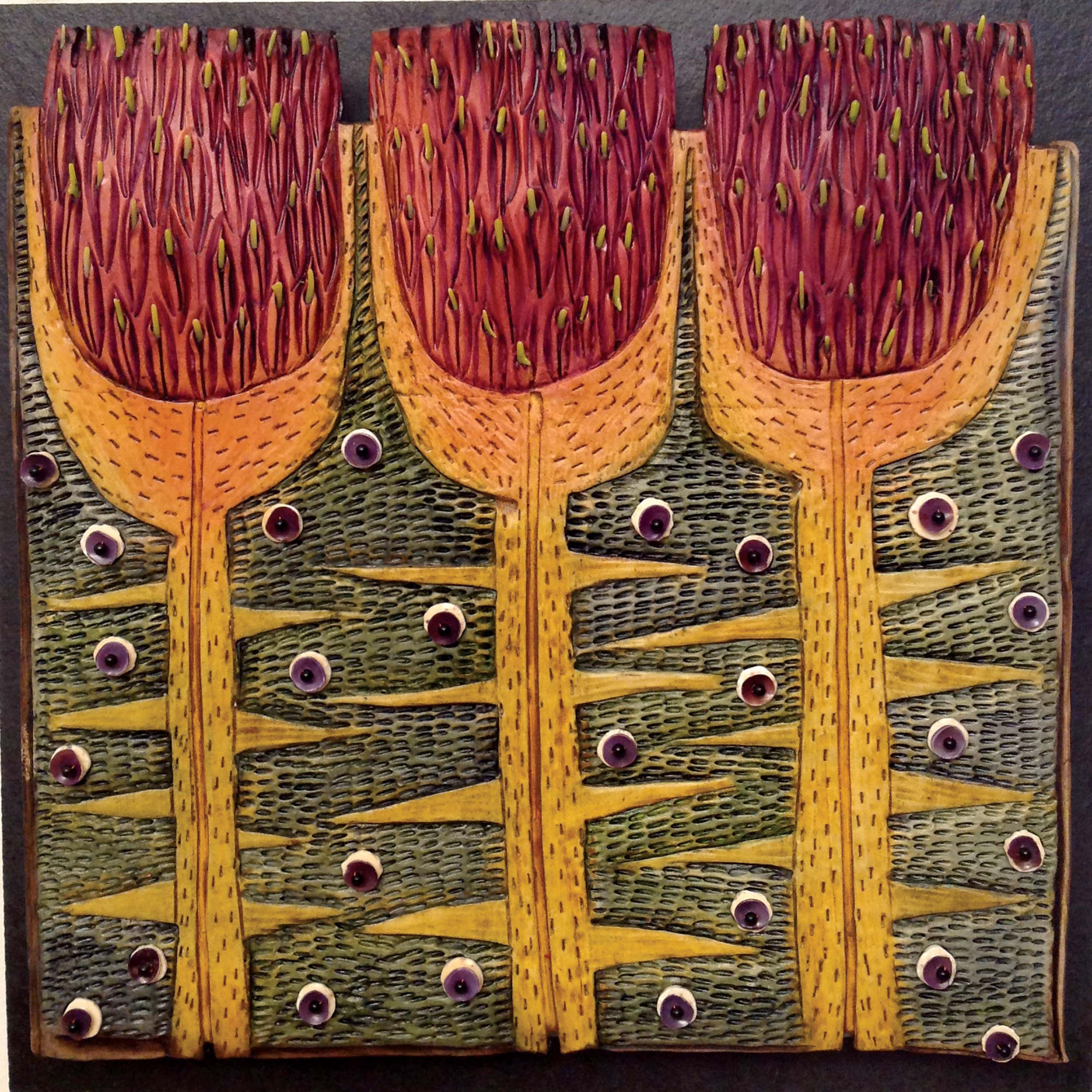

In her third year at the Scottsdale event, Vicki Grant creates with porcelain clay, integrating hardwoods, metals and other natural elements. She hand-tools the green clay, then burnishes and, after firing, embellishes with indigenous materials including cactus pods, gemstones, woods, silver, copper, bone, antler and feathers. She does not use glazes but prefers to hand rub oil pigments layer by layer to achieve the desired patina and hues.

“While some processes to create these forms have similarities to the Native American Indian pottery traditions, the outcome is unique and more contemporary in style,” says Grant, who practiced architecture for 30-plus years after graduating from the University of Maryland School of Architecture. She retired six years ago to pursue her artwork.

Her architectural background established design principles that transferred well into her sculptural artwork. But, she keeps her eye on the living world: “I have always felt that the most amazing forms, structure, color and textures are found within nature, and that exposure to these elements has been my inspiration and teacher.”

- Michael Jones, “Copper Crowned Desert Gate”, 16 feet

- James Ayers, “Guardians of the Black Hills — Lakota” Oil on Canvas | 36 x 60 inches | 2014

- Kirk Randle, “Scouting the Herd” Oil | 36 x 72 inches

- Curt Mattson, “Curt – Loop Full of Fight” Bronze | 25.75 x 27 x 8 inches

- James Ayers, “Apache Sentinels”, Oil

- Curt Mattson, “Letter From Home”, Bronze

- Kirk Randle, “First Snow at the Grand Canyon”, Oil, 48 x 60 inches

- Vicki Grant, “Whimsical Garden”, Mixed Media

No Comments