09 Jun The Ferus years

The rumors about New York not taking the Los Angeles art scene seriously have always been true, with one exception — the Ferus Gallery. Until a recent slew of books appeared on the subject, the gallery’s accomplishments had been tucked away as ancient folklore.

Stories about the Ferus years were swapped among local artists as if they had happened centuries ago. In reality, the tale of the Ferus Gallery can be traced back to 1957 when the eccentric curator, Walter Hopps, teamed up with the even more eccentric artist, Edward Kienholz, to open a gallery on La Cienega Boulevard. What began as a ploy to exhibit their friends’ work wound up rewriting art history.

Part of the reason Los Angeles had gotten a bad rap by the New York art world can be written off to envy. Blessed with gorgeous year-round weather, an enticing Hollywood mystique and a reputation for promoting a hedonistic lifestyle, Los Angeles has always been a magnet for young people looking to seek their fortune. During the 1950s and early 1960s, that group included a number of people determined to become visual artists. They set up studios, often in Venice, and began experimenting with non-traditional materials to make art.

The town’s thriving car culture influenced Billy Al Bengston to create paintings sprayed with candy-color auto lacquer onto dented sheets of aluminum. Peter Alexander’s breakthrough was directly tied to his interest in surfing and working on his Fiberglas and resin surfboards; he wound up using pigment-infused liquid resin to cast sculpture. Ed Ruscha utilized gunpowder and various food substances (though no one but Ruscha knows why). Because Southern California artists largely shied away from working with oil on canvas, their East Coast counterparts viewed their efforts as lightweight. Ferus changed that equation.

What happened was Kienholz and Hopps put together a gallery on an anemic budget, more concerned with gaining exposure for the artists than sales. Ferus took plenty of risks, giving the first solo shows to Larry Bell, Ed Ruscha, Ken Price, Robert Irwin, Ed Moses and Billy Al Bengston. But by 1958, after one year of operation, Kienholz wanted out. He preferred to concentrate on his own art, eventually securing a considerable reputation for his edgy tableaus composed of found objects.

Kienholz sold his share of the gallery to Hopps for $1,500. Though he possessed a deadly eye, Hopps was undisciplined and had a hard time showing up for work — sometimes vanishing for weeks — and could never have run the gallery on his own.

Blum was a charismatic character, blessed with a rich baritone voice and looks often compared to Cary Grant. He was the perfect gallery front man. Even more important, Blum had intuitions about artists that proved spot-on, and instinctively knew how to promote their work. In addition, he brought a sense of professionalism to Ferus. He ran the gallery with a strong hand, which was much needed given the macho personalities of the artists.

Before Blum arrived, for example, the gallery refused to give a 10 percent discount to their few loyal clients — a standard practice in the New York art world. One day, Joseph Hirshhorn (of the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C.) arrived at the Ferus, selected a group of works and promptly walked out empty-handed when he was told there would be no discount. Blum quickly made sure that would never happen again.

Another challenge to the business was that Ferus operated like a cooperative, with the artists voting on who could join the gallery. Blum rectified that policy when he found out the great Richard Diebenkorn was denied membership because he was from Northern California and made figurative paintings.

Ever ambitious, Blum formed alliances with some of the more important galleries in New York, including Pace. Early on, Pace owner Arne Glimcher watched Larry Bell become Ferus’s biggest star and proposed a show of his glass cube boxes. In Hunter Drohojowska-Philp’s valuable book on the early Los Angeles art scene, Rebels in Paradise, she recounts Blum asking Bell how much it would cost to fabricate 20 boxes — 10 for Pace and 10 for Ferus.

When Blum explained to Glimcher that Bell’s costs were $1,000 per sculpture, Pace immediately put up $20,000. Bell received his check, marveling at his good fortune. Unfortunately, the artist shared news of his windfall with fellow Ferus artist Billy Al Bengston, who reacted by marching into Ferus to read Blum the riot act, demanding $20,000 for himself. When Blum explained it “didn’t work that way,” Bengston promptly quit the gallery.

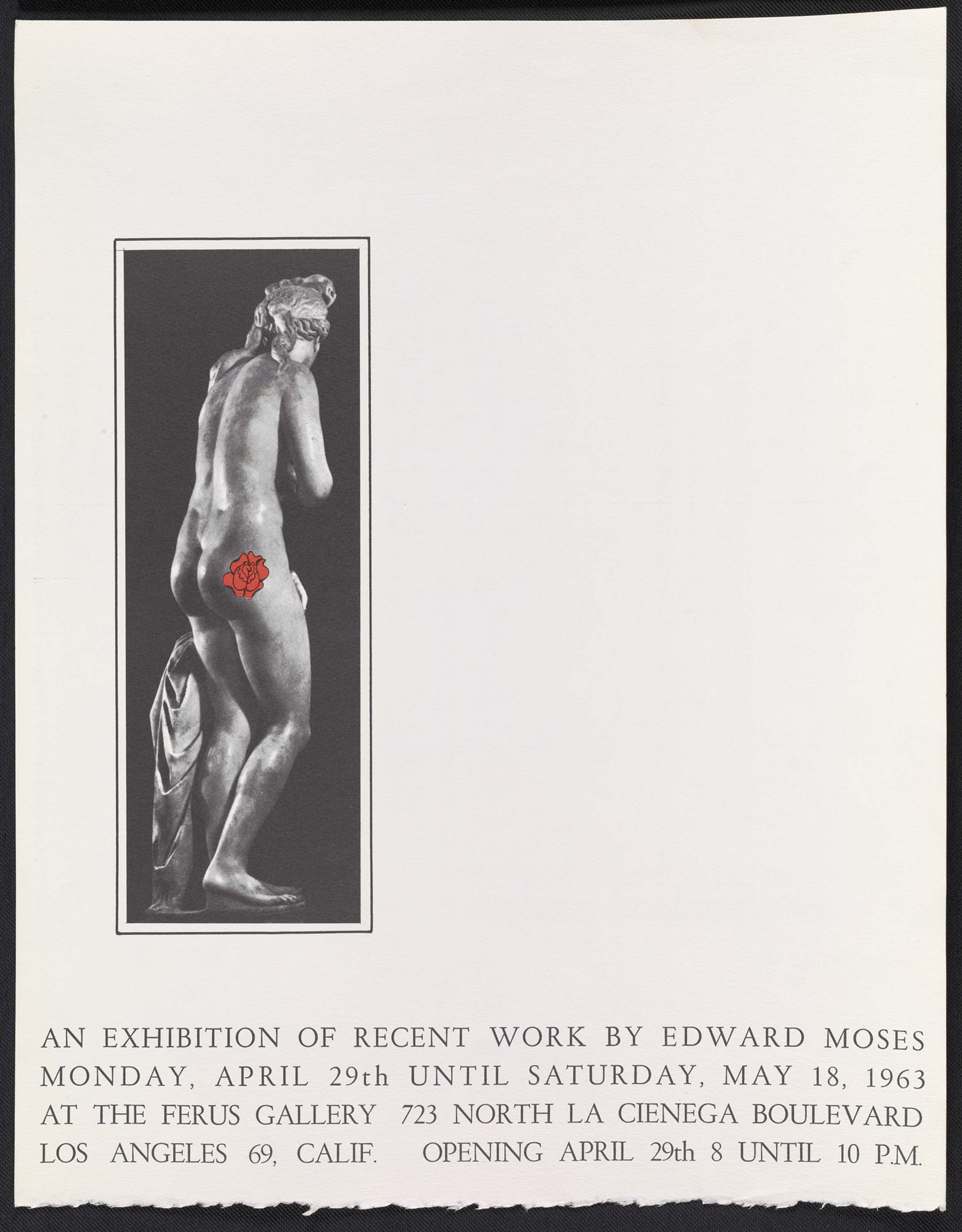

Bengston wasn’t the only difficult Ferus personality. Ed Moses ranked among that illustrious list. During my own stint as a gallery owner (Acme Art, San Francisco, 1984 to 1988), I once pitched Moses on joining my stable. One night, we sat in a sushi bar in Venice, along with his friend, Eric Orr, whom I represented at the time. The conversation went something like this: “So Ed, I’d very much like to show your work,” I said.

“Well, how do I know you’ll pay me when you sell a painting?”

Gesturing to Eric Orr, I said, “Why don’t you ask your soul brother over there if we paid him.”

“No worries, Polsky pays his bills,” nodded Orr.

Ed Moses then looked me in the eye, and in all seriousness said, “Well, how do I know Eric is telling the truth?”

Needless to say, despite Moses’ illustrious background as an original Ferus artist, we never showed him.

But back in the day, Moses remained loyal to Blum, who managed to move on from the Bengston defection and other acts of rebellion by gallery artists. In 1962, Walter Hopps sold his half of Ferus to Blum and accepted a job as the director of the Pasadena Museum of Art. Hopps did extraordinary things in Pasadena, including organizing Joseph Cornell’s and Marcel Duchamp’s first American retrospectives. Meanwhile, Blum began spending more time at Leo Castelli’s gallery in New York, where he secured shows with Roy Lichtenstein, Frank Stella and Andy Warhol.

As every student of art history knows, Andy Warhol had his first exposure in Los Angeles — not in New York — at Ferus in 1962. This was the famous show of 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans that changed art history and popular culture. After selling six canvases for $100 each, Blum had an epiphany. He called each of the buyers and convinced them to cancel their purchases so he could keep the paintings together as a set.

According to Blum, he then explained his idea to Andy, who was elated, and offered to sell the group for $1,600 on time payments of $100 a month. This story has since become classic art-world gospel. Only it may not have been true.

According to Joseph Helman, who went on to become Blum’s business partner, Blum was able to secure the show only because he guaranteed Warhol he would buy everything. At the conclusion of the exhibition, he called Warhol and told him only six paintings had sold. Warhol allegedly said to Blum, “That’s too bad, but you still owe me $1,600.” Blum told the artist he didn’t have any money. Warhol, who was apparently quite upset, responded, “Yeah, but some day you will.” Warhol then reluctantly agreed to accept $1,000, which Blum paid off over the next 24 months.

By then, the Soup Can paintings were worth $1,000 each. To Blum’s credit, he managed to keep them together until 1996, when he sold them to the Museum of Modern Art for $15 million. Today, the paintings would be worth approximately $10 to $12 million apiece.

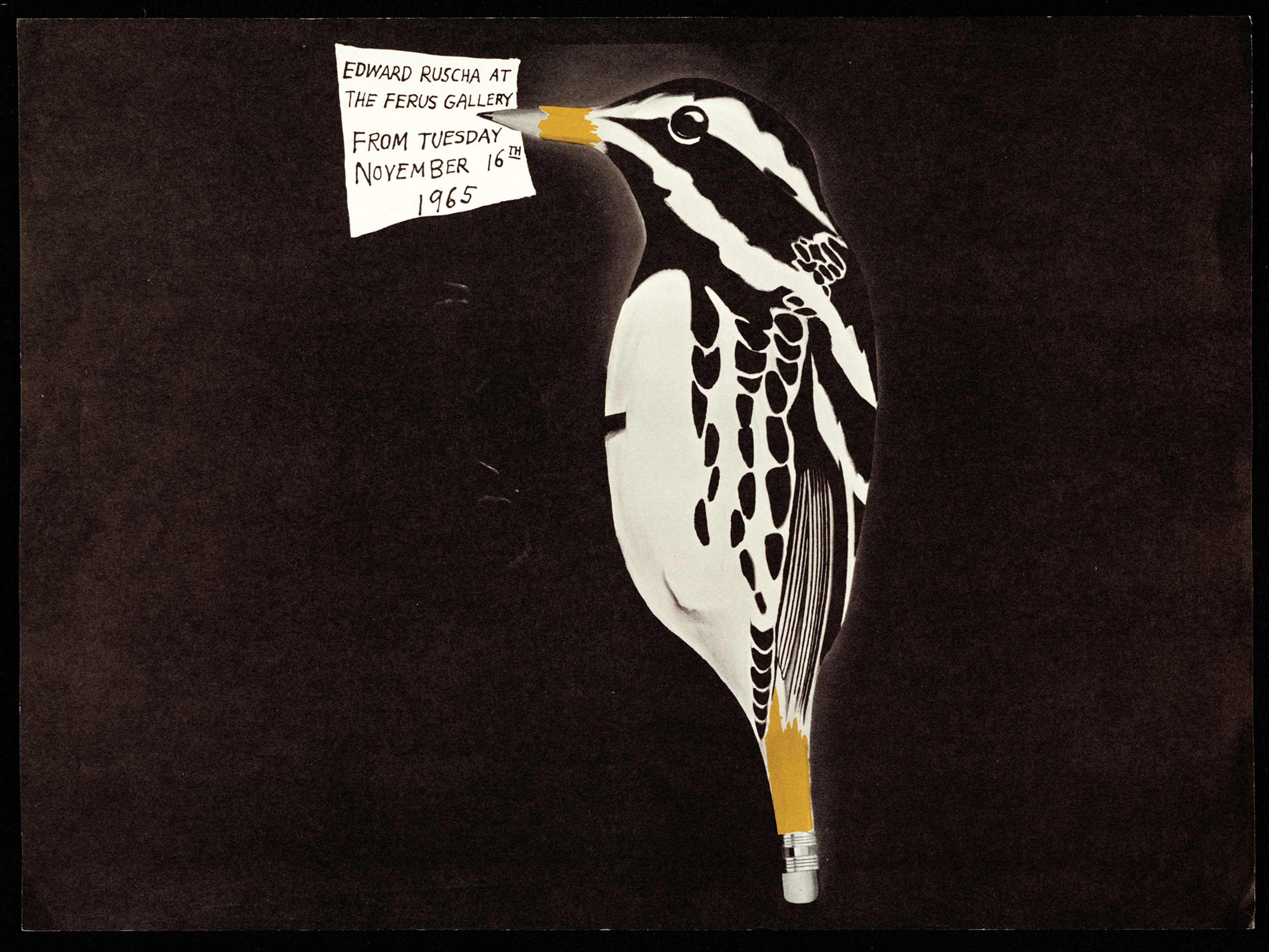

Another illustrious Ferus alumnus was Edward Ruscha, one of the first artists to introduce language as subject matter. He was also known for his obsession with Los Angeles iconography: the Hollywood sign, Norm’s restaurant and the local Standard gasoline stations. Like Ed Moses, Ruscha was another painter I wanted to exhibit. Though, when I approached him he already had strong Bay Area representation. With that in mind, I called the James Corcoran Gallery, the artist’s Los Angeles dealer, to try and buy a show outright from them.

My proposal was simple. I wanted to commission Ruscha to do a series of paintings depicting ancient Los Angeles imagery: Ice Age animals found at the world famous La Brea Tar Pits. At the time (1980s), Ruscha was airbrushing shadowy black-and-white imagery, such as howling coyotes and Joshua trees, and could have easily segued into woolly mammoths and saber-tooth tigers. Unfortunately, something got lost in the translation when my offer was conveyed by Corcoran to Ruscha.

Jim Corcoran called me up and said, “Sorry, Ed turned you down.”

“What exactly did he say?” I asked.

“Polsky wants me to paint dinosaurs?!” Corcoran chuckled. “They’re not dinosaurs … they’re Ice Age creatures, as indigenous to Los Angeles as the Hollywood sign!” I yelled, in exasperation.

Fortunately, I had more luck with the group of artists who followed the Ferus painters.

Irving Blum’s operation paved the way for a number of significant players, who emerged in the 1970s, including Vija Celmins, Daniel Douke and Charles Arnoldi.

I asked Arnoldi, who secured his reputation by constructing paintings out of eucalyptus tree branches, “During the 1970s, when you were first starting out, what was the word on the streets about the Ferus Gallery?”

With a twinge of awe in his voice, Arnoldi said, “That was the place where you wanted to be, especially as a young artist. They were like a club — like a motorcycle gang — their artists were so tight-knit that it created this incredible buzz that attracted everyone who walked down La Cienega Boulevard.”

I also asked the realist painter Dan Douke, whose current work depicting Apple computer boxes speaks about the gap between reality and illusion, the same question. He responded, “The Ferus Gallery kicked the door open for Los Angeles to become a hip art community. As a result, I was able to thrive in L.A. as an artist. Without Ferus, the city would probably not have developed into the significant arts community it is today.”

But all good things must come to an end and the Ferus Gallery was no exception. In 1967, after a decade of operation, Ferus closed. Not long after, Blum teamed up with Arne Glimcher to form Ferus/Pace in Los Angeles, which ran for two years. Blum made his mark again when, in New York City, he partnered with Joseph Helman, forming the 57th Street powerhouse operation BlumHelman Gallery. Ultimately, he moved back to his beloved California, briefly opening a space in Santa Monica, before semi-retiring.

Now 83 years old, Irving Blum has become the equivalent of a professor emeritus and is always given a warm reception whenever he shows up at art world events. He is the closest thing we have to art world royalty. Ditto for the Ferus Gallery. Their uncanny pinnacle remains.

- “Ed Ruscha, Actual Size” Oil on Canvas | 67 x 72 inches | 1962

- This 1963 Ferus Gallery ad announced an exhibition of work by Edward Moses. Irving Blum Gallery and Ferus Gallery announcements, 1961-1973. Archives of American Art

.jpg)

.jpg)

No Comments