01 Dec In the Abstract

Tell you what,” Poteet Victory says in his laid-back Oklahoma drawl as we enter his second-floor studio at McLarry Modern on Santa Fe, New Mexico’s Canyon Road. “I’ll give you a name. You tell me what you see, but you gotta get your mind in a space, and say the first things that pop into your mind. Ready? … Georgia O’Keeffe.”

“Pastels. Flowers. Sensual. The Pedernal (the flat-topped mountain near Abiquiú that O’Keeffe often painted).”

The 64-year-old artist pulls out a small painting — pastel blue, like the New Mexico sky, flowers, antlers — that he hasn’t gotten around to abstracting. “When I think of O’Keeffe, I think of her flowers, really sensuous, female. The horns. The blue sky. And I had the Pedernal at the bottom, the flat top, and that may go back in there because I kinda see that, too. But I ask people all the time what they see, and they say flowers, antlers, and then I pull out this and ask, ‘Does it look like that?’”

Victory has become absorbed with a new series of 4-by 4-foot contemporary abstract paintings — Abbreviated Portraits — of pop-culture figures that his mentor, Harold Stevenson, says “completely blows away Modern art.” He was working on No. 12 in the series when we met on a cool September morning, but has been selling only prints (starting at $1,000) until after museum exhibits. Well, a 6-by 6-foot version of Marilyn Monroe did sell — for $150,000 after only two days.

“You can have technique and style, but very few artists can come up with an idea that can be a series,” says Chris McLarry, Victory’s longtime friend and business partner at McLarry Fine Art. “This idea, this concept is totally new. He’s a real innovator.” For Victory, the idea began on an airplane in Dallas. “I don’t carry a cell phone,” he says. “I’m old school.

But it fascinates me that people are so plugged into this thing, like they can’t do anything without these things. So the plane landed, I was sitting in the back and the captain comes on and says, ‘You’re free to use your phones,’ and it was almost like a command. Everyone picks one up, starts texting and I started thinking, ‘It seems to me that this is where the world is going. I can see people not knowing how to spell anymore because they’re trying to abbreviate everything. Maybe you could abbreviate an image …’”

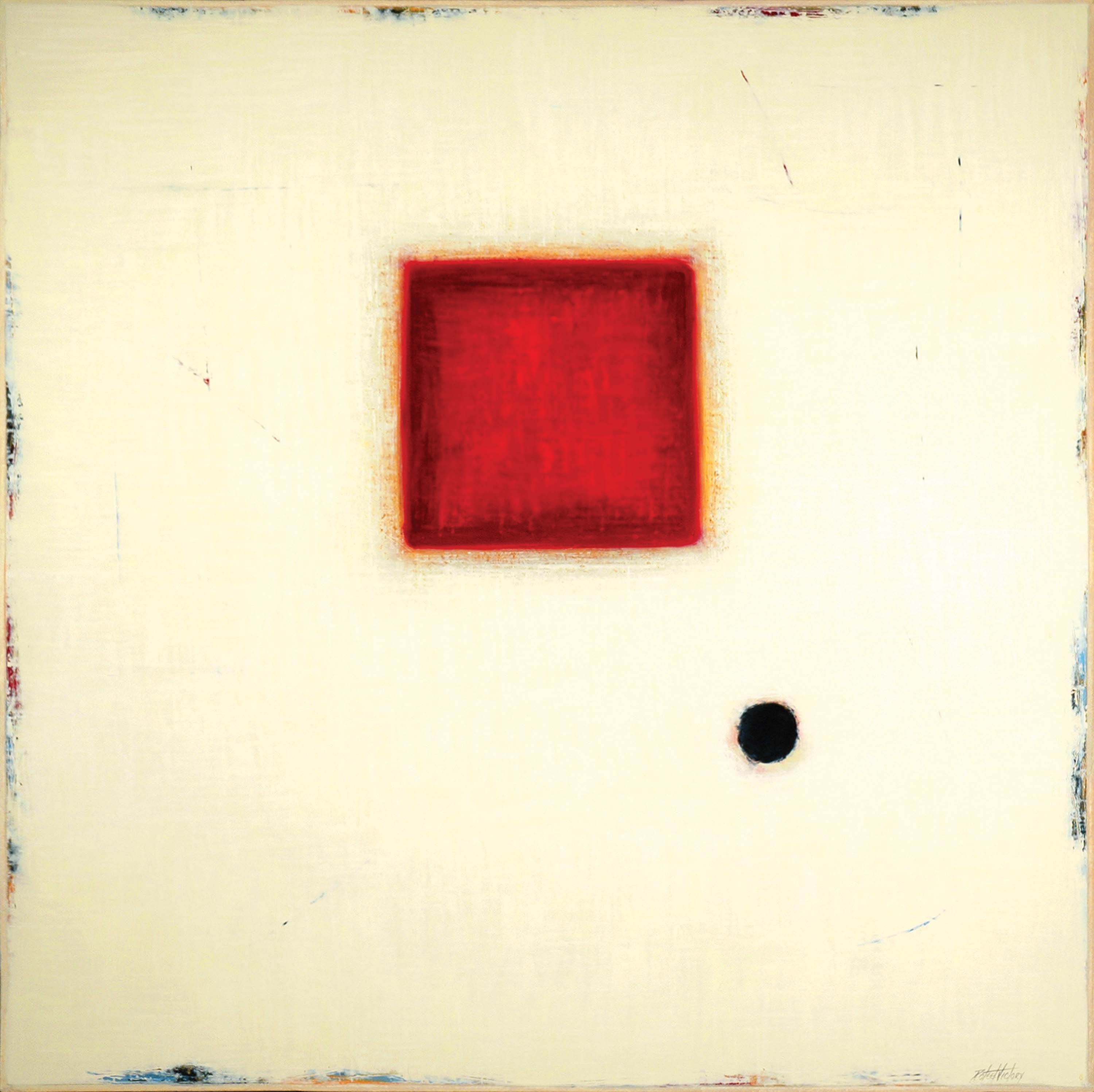

Sometime later, he started an abstract painting. White painting with a red square in the center. “All of a sudden,” he says, “I put a black dot on it, and that was Marilyn Monroe.”

White dress. Red lipstick. Beauty mark.

“In your own mind, you will paint this thing yourself,” he says.

Elvis Presley? Black. Pink diagonal to connote movement.

Howard Hughes? Yellow-khaki, and a symbol connoting the Spruce Goose’s wooden wing. “This one I didn’t put a shiny finish on because Hughes wasn’t that type of figure,” Victory says. “He was much more in the background.”

Lucille Ball? Red and white polka dots.

He doesn’t plan any of this. Just paints what pops into his head.

“Neuroscientists say we don’t store images of people in detail in our brain,” Victory says. “They’re floating around in the back of our brain in geometric shapes and forms and colors, and then when you get ready to recall it — boom — it all comes together and you see it.”

John Wayne? “Number one, he’s Captain America, so the painting’s red, white and blue, and the center part is larger because I saw him as bigger than life. But he was a cowboy, so I put a tooled leather thing there. But also the hat. Only instead of the hat, I just put the brim.”

The brim’s a wavy line. But carry that through. … Victory grabs a pencil and sheet of paper and quickly transforms that symbol into the sketch of a hat.

The Beatles? “John, Paul and George across the top, and Ringo down there (similar to the cover of the 1964 album Meet the Beatles!). The butt end of a guitar, the neck, music lines. And I remember when they first came onto the scene on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” wearing gray suits, string ties. That’s what I was seeing.”

He needs at least 15 portraits for a museum show, but “I know I won’t stop there.”

Victory seems to be not only reinventing modern portraiture, but himself. Which is no surprise.

He grew up poor in southeastern Oklahoma, drawing as a kid and rodeoing in high school. While in Idabel, he met and was mentored by Stevenson, a major player in New York’s 1950s art scene whose The New Adam is part of the Guggenheim’s permanent collection. Stevenson introduced Victory to Andy Warhol when the young artist headed to New York to study at the Art Students League. “Andy was the first person I met in New York City,” he says.

In 1988, Victory headed to Santa Fe, bartending “to feed my painting habit.” He met McLarry, and before long they were selling Victory’s paintings from the back of McLarry’s SUV all across the country.

“Most artists are emulating someone,” McLarry says, “but Poteet’s truly an artist that found his own voice that others have emulated since. In the art business, you’re always looking for someone who has come up with a new voice.”

Three-eighths Cherokee and Choctaw, Victory started doing Indian and Southwestern images. In 2001, he decided to change. “I informed my galleries, ‘I’m going completely abstract.’ And they said, ‘Don’t do that. You’ll confuse your clients.’ I said, ‘I just feel that I have to, and, by the way, I’m doubling my prices.’ And they said, ‘You can’t do that.’ But I did, and when I did, my sales went through the roof.”

Change is important, he says, and taps his temple. “People get locked in because they get locked in up here,” he says. “I don’t think it actually exists out here. People like to see you progress.”

- “LVS” | Oil on Canvas | 48 x 48 inches

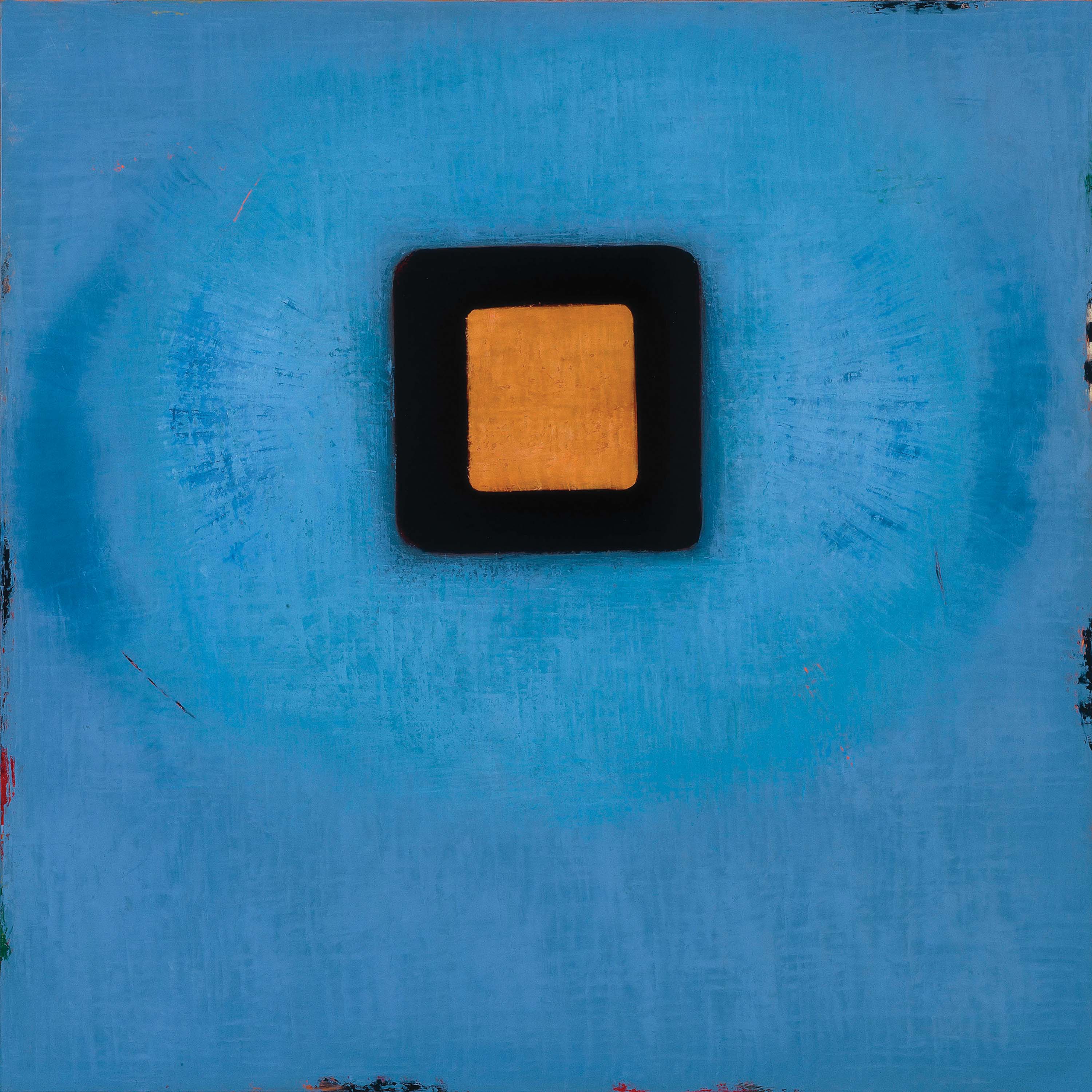

- “JCK NKLSON” | Oil on Canvas | 48 x 48 inches

- “PL NWMN” | Oil on canvas | 48 x 48 inches

- “Lu C” | Oil on Canvas | 48 x 48 inches

No Comments