01 Feb Len Chmiel

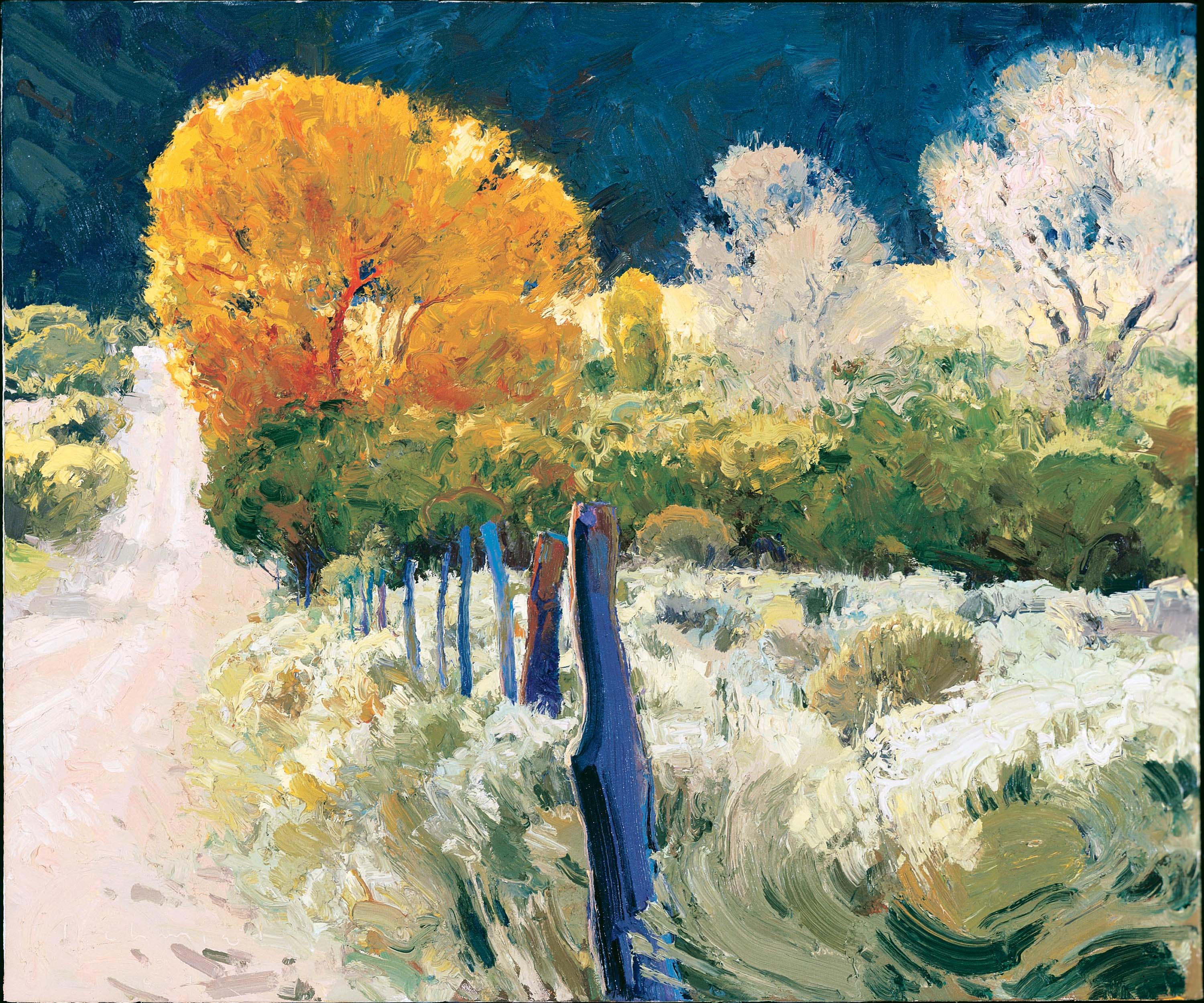

TRANSLUCENT NEAON WANDS IS A PAINTING of an Aspen forest in Colorado, made in the early evening. Or is it? Dimly lit by the fading rays of the setting sun, Translucent Neon Wands defies most conventional landscape formula. Tree trunks are pushed up against the surface of the canvas from one side to the other, obliterating both the horizon and spatial depth. Color, or more accurately color differentials, delineates space as much as recognizable forms. Even the painting’s title refuses to acknowledge nature as a source, suggesting that for Len Chmiel, the viscous, material quality of paint as it rests on the canvas surface constitutes a landscape as much as the assemblage of space, perspective and topography that we traditionally recognize as such. While the idea that representation and abstraction are mutually exclusive or inherently different has occupied many historians of Western art, Chmiel refuses to acknowledge the divide. His work suggests instead that it can be had both ways, that three-dimensional landscapes can be credible as such without denying the physical reality of the two-dimensional canvas or the substantive nature of paint itself.

This sense of a direct and material connection — between the surface of the painting and the surface of the earth — is inherent in the approach of this artist who sees humanity in the physical qualities of land: “I really believe that I came from the dirt … it’s the old dust-to-dust thing. I garden, I look at the way plants grow and that tells me how to structure the landscapes I paint. I don’t feel that apart from the earth. I grow almost everything I eat and I hunt. I feel this real physical and emotional and spiritual connection to the thing. I actually get into a dialogue with what I’m painting — I impose myself on it and if I have a reaction to something I gradually drift into another state of mentality.”

This dialogue between artist and nature, between paint and the land it comes to represent, situates Chmiel’s art within the continuum of historical change that began in late 19th-century France, when a loose-knit group of landscape painters began to investigate the optical qualities of light and its relationship to modern vision. Mediated by the rise of technology as a governing force in their everyday lives, the Impressionists (as they came to be called) pictured a changing relationship between individuals and their visual environment, between the artist and his subject as he moved throughout the city and into the countryside. In the process, they shifted the focus of art away from the allegorical myths and historical dramas that dominated exhibition culture of their day. Instead, they sought to integrate the changes imposed by the industrial revolution upon individual vision and social culture within the highly structured process of painting itself. This idea — that painting reflects the artist’s individual subjectivity within a rapidly changing world — launched an artistic revolution that challenged fundamental concepts of both perspective and purpose in art. As they broke down light and form into basic elements of color and line, Impressionists called attention to the synthetic nature of painting.

Although his art is in many ways reliant on the series of breakthroughs that began in 19th-century France, Chmiel’s work is not simply a summary of Impressionist values. The specifics of the landscape matter less than the fact that the artist was present; by emphasizing his encounter with nature as a highly personal, intimate experience Chmiel’s work relies equally on his own familiarity with the landscapes he paints as it does the fundamental conceit of modern art.

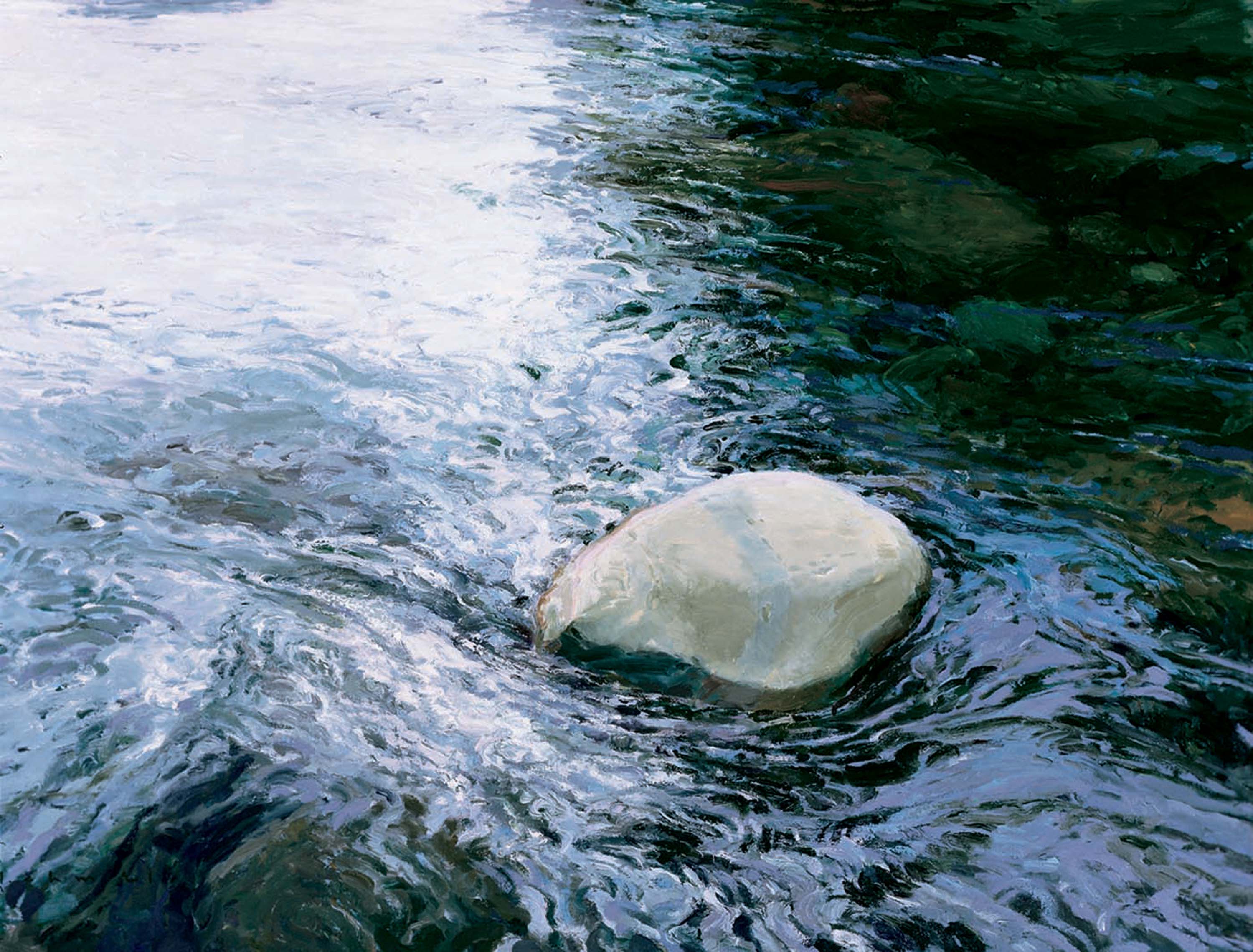

What we see in works such as Rock Solid is not the landscape itself but his connection to it, a relationship with the natural world that balances abstraction and representation. In this painting, Chmiel focuses our attention on a decidedly non-spectacular rock resting in mid-stream in the Merced River in California’s Yosemite National Park. Unexceptional on its surface, this rock would undoubtedly go unnoticed by most people, especially in a landscape such as Yosemite’s. Without a horizon, shorelines, trees or other more standard elements of a river scene, the image contains nothing other than nature on an everyday, accessible scale. Drawing our attention to its smooth surface, its solid form and the ripples of light created in the water as it flows by, this landscape is as much a mental image as a physical setting; we experience it as the artist did, at that time, on that day.

Early Life, Illustration and Influence

The visible connections between Chmiel’s mental and physical universe can be traced also to his understanding that the contemplation of nature is itself a luxury. Like many Western artists before him, Chmiel initially earned a living in illustration, fulfilling the graphic demands of commercial clients in the aerospace industry and later as a freelancer. His gravitation toward a career in the arts was initially something of a rebellion from a stern and rather unstable upbringing. Chmiel was born in Chicago in 1942, where his father worked in construction, installing large scale, industrial mechanics such as printing presses and hydroelectric generators. During the economic recession of the late 1940s, his father sold the family home and purchased a house trailer, which he towed to Southern California, along with his wife and four young children in 1950. At age twenty Chmiel entered the commercial art world as an assistant art director at Cannon and Sullivan Technical Publications, a Buena Park graphic arts firm specializing in aerospace and corporate clients. There he met and married Donna Byerrum in 1963, and within a year went to work for Hughes Aviation.

He also began three years of night classes at the Art Center College of Design (then in downtown Los Angeles), a grueling schedule that cost him his marriage by 1967. Chmiel found at Art Center however a fresh source of inspiration in the figure of Donald “Putt” Putman, an instructor and former circus clown who later painted scenery and backdrops for MGM films. Putman emphasized the importance of painting for individual fulfillment over art-world expectations: “I paint to please myself and the pleasure is contagious,” Putman declared. Recognized for his interest in Western subjects long before there was a substantial collector base for such themes, Putman found in the West a “freedom to relate an exciting idea.” Although Chmiel would eventually leave behind the narrative drive of commercial art to focus on light and landscape, Putman’s emphasis on personal joy would remain a guiding influence: “I got from Don those necessary tools to produce a painting, but more importantly his philosophy was just wonderful.”

Place, Water and Risk

In October of 1971, Chmiel moved from Los Angeles to Denver in order begin his artistic career anew. Determined to “make it as a painter,” Chmiel quickly connected through drawing classes and studio visits with Buffalo Kaplinski, George Carlson and sculptor Ken Bunn, who were part of a larger group of local artists interested in Realism. Since termed “The Denver School,” Chmiel describes them as a loosely associated “free-thinking community of guys that were so good at what they did … they were producing in a traditional manner, a representational manner, but with such personal insight that they were all after something different. Every one of them had a separate interpretation.”

Linked together mainly by their shared interest in the essential academic foundations of representational art, they exhibited together in group shows within an emerging gallery and museum scene devoted to the American West as a region with a distinct cultural history and visual identity. Meanwhile, the thriving tourist economies of Western destinations such as Santa Fe and Taos fueled a collector’s market for paintings of the historical “Old West” at the same time that it increased interest in those artists who appeared heirs to its traditions of landscape and narrative genre. During the late 1970s and ’80s, Chmiel exhibited at Sandra Wilson Galleries in Santa Fe and Denver and Stremmel Galleries in Reno, but never fully identified with the more sentimental, nostalgia-based aspects that dominated much of the commercial gallery scene, preferring Putman’s emphasis on painting for oneself over catering to the expectations of collectors or dealers.

In 2001, Chmiel moved from the Denver area to Hotchkiss, Colorado, where he built a studio and eventually a house. A town of approximately 1,000 people and an elevation of more than 5,000 feet, Hotchkiss provides Chmiel with relative solitude but also proximity to a creative community of artists, musicians and writers. Most importantly, his mesa home is conducive to the self-sufficient and sustainable relationship with the environment on which his art is based. Chmiel maintains a vegetable garden, fruit trees and a small vineyard; much of his meat he hunts and he is a skilled fly fisherman. Hotchkiss provides direct access to a variety of visual landscapes, from rugged mountains to high, arid desert, an intricate river system and seasonal changes that range from winter snowfalls to spring storms and hot, dusty summer days. The dynamic nature of his surroundings is critical to an artist whose work in many ways is based on change and flux, and Chmiel calls it as “close to perfect as I have found … I could spend the rest of my life exploring/painting the possibilities of the land. It is intimate yet expansive depending on how I am feeling at the moment.”

Of the various landscape elements that surround Chmiel in Colorado, it is water on which he most often fixates. Chmiel’s interest in water as a painterly subject emerged in the 1970s while, on a painting trip to Yellowstone National Park with Kaplinski, he became entranced by the transparent qualities of the park’s signature geothermal pools. Ever since, water has provided Chmiel with a landscape subject in constant and visible flux in which volume, color and form change from one moment to the next. In the years since, Chmiel has painted a series of works devoted to exploring the visual nature of water. Unlike his 19th century predecessors, however, Chmiel refuses to attribute a didactic purpose to his self-described Water Series, insisting instead that the chal- lenges of form and design in conveying its fluid nature are their main focus: “I have spent God knows how many hours trying to figure out what is going on with water … it’s just mesmerizing. Cross currents and eddies; how the depth of color intensifies, becomes richer below the surface; how water can be flowing in one direction but moving back upstream around a rock at the same time.”

While this intense interest in the visual properties of water recalls the “art for art’s sake” motto of James McNeil Whistler, it also belies his larger interest in risk and risk-taking as a dividing line between art of importance and that which is not. Since leaving the illustration industry in 1971, Chmiel has pursued landscapes and compositions that defy traditional art’s historical notions of the picturesque or the sublime. Of Gin Clear, Frying Pan River, Colorado, Chmiel claimed that when he first contemplated painting the scene, he thought, “Naw, no one is going to understand this,” finally convincing himself that it’s “weird, but why not?” This act of discovering new landscapes within known lands is highly dependent also on the notion that the fragments or seemingly minor details of nature — such as melting snow and running water — are potentially as significant as the more monumental features of moun- tains and waterfalls. Chmiel is like- wise uninterested in the allegories that occupied his historical predecessors such as timelessness and geologic history. Instead, he prefers to work with finite and discreet spans of time and their impact on perceptible changes within the landscape, as in the momentary shadows cast by a rising sun or the glitter of light on moving water.

It is [Chmiel’s] more intellectual perspective on reality as an experience that is mediated by the eye and the mind that places him in a unique position with the nexus of contemporary art being made in and about the American West. In a genre that speaks often of authenticity and the artistic commitment to the traditional or academic values of painting, Chmiel’s ability to fuse abstraction and Realism on the surface of a single canvas represents an artistic feat. It also places him in a somewhat awkward position relative to the world of contemporary artists devoted to the values of traditional Western art, such as storytelling, setting and memory. Chmiel began showing in exhibitions devoted to the documentary ideals of historical authenticity beginning in 1986, when he first exhibited at the Artists of America Show at the Denver Historical Society Museum. In 1990, Chmiel began showing with the National Academy of Western Art in Oklahoma City’s National Cowboy Hall of Fame, which would become the Prix de West. Two years later, he was included in The Denver Seven, also at the Cowboy Hall. Together, these exhibitions effectively grounded the return to Realism in art of the West as a narrative-based, regional phenomenon that reflects the influence of history and of place in contemporary art. In 2004, he was invited to exhibit at the Autry National Center’s Masters of the American West, a smaller but equally robust exhibition that includes fellow Colorado artists Ken Bunn and George Carlson.

Although Chmiel’s work is now a fixture of the circuit of galleries and museums that explore contemporary Western art as a continuation of traditional values, it remains at odds with certain aspects of these exhibitions and their audience. Despite his early illustration work, he professes a distinct lack of interest in narrative, or the idea that art must tell a story in order to engage. His willingness to flaunt the conventional notion that art acts a window into the visible world is evident in Life Imitates Art, the first painting he exhibited in the Autry’s Masters; the shadow cast by the living deer is not its own but its historical impression, a larger than life pictograph whose looming visage is the painting’s ostensible focus. Yet Chmiel’s facility with paint transforms this obvious illusion into an image so believable that it forces the visitor to question the very fundamentals of representational art and Realism in general.

Nearly 150 years after the Impressionists made their break from the three-dimensional landscape painting, consensus on what constitutes Realism in art remains surprisingly elusive. Chmiel’s will never extricate itself fully from the places — Colorado, New Mexico, California and Wyoming — on which it is based. His foregrounding of the academic value system, especially spatial depth and color, situates his work firmly within a relatively traditional field of artists, collectors and institutions who are interested in history and identify with its ideals. Yet his art and his life also evince a level of environmental consciousness and an emphasis on a dynamic and sustainable interaction between the artist and the world that is part of a decidedly post-modern phenomenon, one that is, as the geographer Ronald Cooke puts it, “re-discovering and re-defining human environmental relations … we are developing a more imaginative response to nature, a renewed interest in natural forms, and a clearer understanding of the ecological interdependence between people and their habitats. [This] fluidity of meaning itself gives freedoms that allow us to sense a new unity between human life and the earth, a reunion of the spirit and nature.”

In calling equal attention to the process as to the picture, Chmiel reminds us that landscape painting is a cultural, rather than a natural, process; it is a tangible product of the interaction between people and nature. For those who investigate landscape with a trained eye, it is an enduring source of inspiration and information. Artists, scientists, academics and museums all interrogate landscapes as evidence of our relationship with nature, whether one of mastery or subservience; of stewardship or symbiosis. This equation is an individual one and as such is dependent on other factors such as background, politics and experience. Chmiel’s art brings to the surface more than the material quality of paint itself — it brings awareness that landscapes and land are separate things, joined by the artist’s intervention and the cultural imagination that we all share.

- “Rock Solid” | Oil on Canvas | 42 x 56 inches

- “Gin Clear, Frying Pan River” | Oil on Canvas | 12 x 16 inches | 1991 | collection of the artist

- “Limelight, North Piney Creek” | Oil on Canvas | 48 x 61 inches | 2010 collection of the artist

- Len Chmiel

- “Fall Parade” | Oil on Canvas | 25 x 30 inches

No Comments