04 Apr Physics and Poetry

FOR SOMEONE WHO FEELS THE WORLD was more aesthetically pleasing 100 years ago, painter Tim Solliday has uncanny luck with finding the perfect studio. For a number of years he painted in the Arts and Crafts studio in Alhambra, California, that had belonged to renowned Western painter Frank Tenney Johnson [1874 – 1939], celebrated for his moonlight technique. Now Solliday occupies another Arts and Crafts bungalow on a cul de sac in the foothills north of Pasadena, where, he points out proudly, Impressionist William Merritt Chase [1849 – 1916] worked for a year.

In the airy, wood-paneled studio warmed by a crackling Batchelder tile fireplace, it’s easy to feel transported to the days of the early California plein air movement. That’s how Solliday first gained recognition, painting in the style of landscape artists influenced by Impressionism and active from roughly 1890 to 1940. Now he’s gone figurative, producing romantic, narrative paintings of Indians, cowboys, settlers and their interactions. The plein air style and the color and bold brushwork for which he’s noted have simply been absorbed into the Western art.

Bespectacled and red-haired, with a trim beard and moustache, the 60-year-old, but still boyish, Solliday is a bit of a dervish, spinning around the maze of his studio to find examples to back up his points, from his own artwork to books on the artists he reveres — even to a clay pot to emphasize a point about the importance of light. He’s prone to leaping from idea to idea mid-sentence. Time with him is like a crash course in figurative and plein air art from 1880 to 1920, which is his obsession; art that he believes was, until recently, repressed by the Modern art establishment. It’s certainly unarguable that with the advent of Abstract art, narrative art fell out of favor. But this is an issue that Solliday constantly worries like a bone.

One thing is clear: He loves what he does. The man is passionate about his craft.

Solliday grew up in the idyllic Palos Verdes community on a bluff above the Pacific. The first artist he was aware of was Norman Rockwell. As a child, Solliday drew so obsessively he was often reprimanded in school. “Drawing was like eating to me,” he says.

Later, he studied with Theodore N. Lukits [1897 – 1992], who was so strict with his students that Solliday spent a year drawing from skeletons before he was allowed into a life class. For a while, he worked as a billboard painter, where another painter introduced him to the work of John Singer Sargent, and Solliday began to find his way. In school, he’d been a square peg in a round hole; in the ’60s and ’70s when most art schools were beehives of the avant garde, he was a die-hard lover of figurative art. Over the years he taught himself about the artists who worked during the golden age of illustration, like Frank Brangwyn, N.C. Wyeth and Alfred Munnings (the British painter, president of the Royal Academy of Art in the mid-1940s, who famously resigned in a BBC radio speech reviling modern art).

Today Solliday is collected by celebrities such as Oprah Winfrey. In both the plein air and Western worlds, he’s high- ly regarded, always invited to such prestigious competitions as the Masters of the American West Fine Art Exhibition and Sale at the Autry National Center in Los Angeles, and the Prix de West at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. He always places his paintings in hand-carved gold-leafed frames that add to their historical romance.

“Tim Solliday’s work is a unique combination of the historic and the contemporary,” says Amy Scott, the Calvin B. and Marilyn B. Gross Curator of Visual Arts at the Autry National Center. “He draws inspiration from turn-of-the- century California and Western artists such as Ernest Blumenschein, Frank Tenney Johnson and Dean Cornwell. Solliday’s work is based on a solid sense of design, pattern and bright, vibrant color.”

Solliday says: “The greatest painters always had the same principles in everything they did, a philosophical point of view in everything they painted, and that was this truth and beauty concept. I wanted to do something beautiful. I’ve narrowed my definition of art down to it should have physics and poetry. Physics means good drawing, good coloring, good understanding of technical things. And then the poetry, that’s harder to define, it’s left up to the viewer.”

But he constantly circles back to Modern art. “I could never get up on a ladder and drop paint on canvas like Jackson Pollock and call that serious art,” he says. “I would consider myself a fraud. Art is about life. There’s not any word I think is more important. When you see good color, it reminds you of life. That’s why the plein air guys are so successful. Their color is life affirming.”

Solliday works first from pencil drawings, then moves to often quite small color studies before he ever works on canvas. He outlines his figures, in the style of mural paintings or poster art. Each painting is a feast of past and present work; his obsessive sketching, plein air paintings he’s done, even photographs. An older painting of a forest becomes the backdrop for a painting of a brave riding meditatively through winter winds.

Figures, he says, are the most difficult to paint, yet he finds his Western work the most fulfilling of his life. “I wanted to tell stories. There’s emotion in the story. See that guy going through the woods? What’s he doing out there in the cold? He’s some kind of royalty, because they didn’t have those beaded bands around their blankets unless they were. You have to have romance.”

He slaps a ball cap on his head, perching before a painting called Spirit Song, destined for the Autry’s Masters of the American West Fine Art Exhibition and Sale. He explains that the strong Southern California light pouring in the picture window behind him is terrific, but too much without the hat brim. Then he goes into a rhapsody on balancing the colors and perspective in the picture, how much he loves the garb worn by American Indians, and how individual elements in the painting came from different sources, but the basic inspiration was a recent powwow held in a nondescript parking lot in Orange County.

“I guess it’s just a little tune you hear in your head,” he adds. “I saw these guys around the drum; that was the tune. And then came the whole finished piece of music when I worked it out here.”

He points at a tree that’s an important element of the perspective. “It can be a design while still being a tree,” he says. “Someone might say I make too much of a design and not enough about a tree. But I’m willing to risk it, to believe my audience is sophisticated enough to understand what I’m trying to say and do. Mostly in the heart. Great art should always be understood on an emotional level.”

At the end of several hours swept away in Solliday’s passions, I’m exhausted. But as I drive away, there’s Solliday standing in the doorway of his exquisite studio, grinning and as exuberant and full of energy as ever.

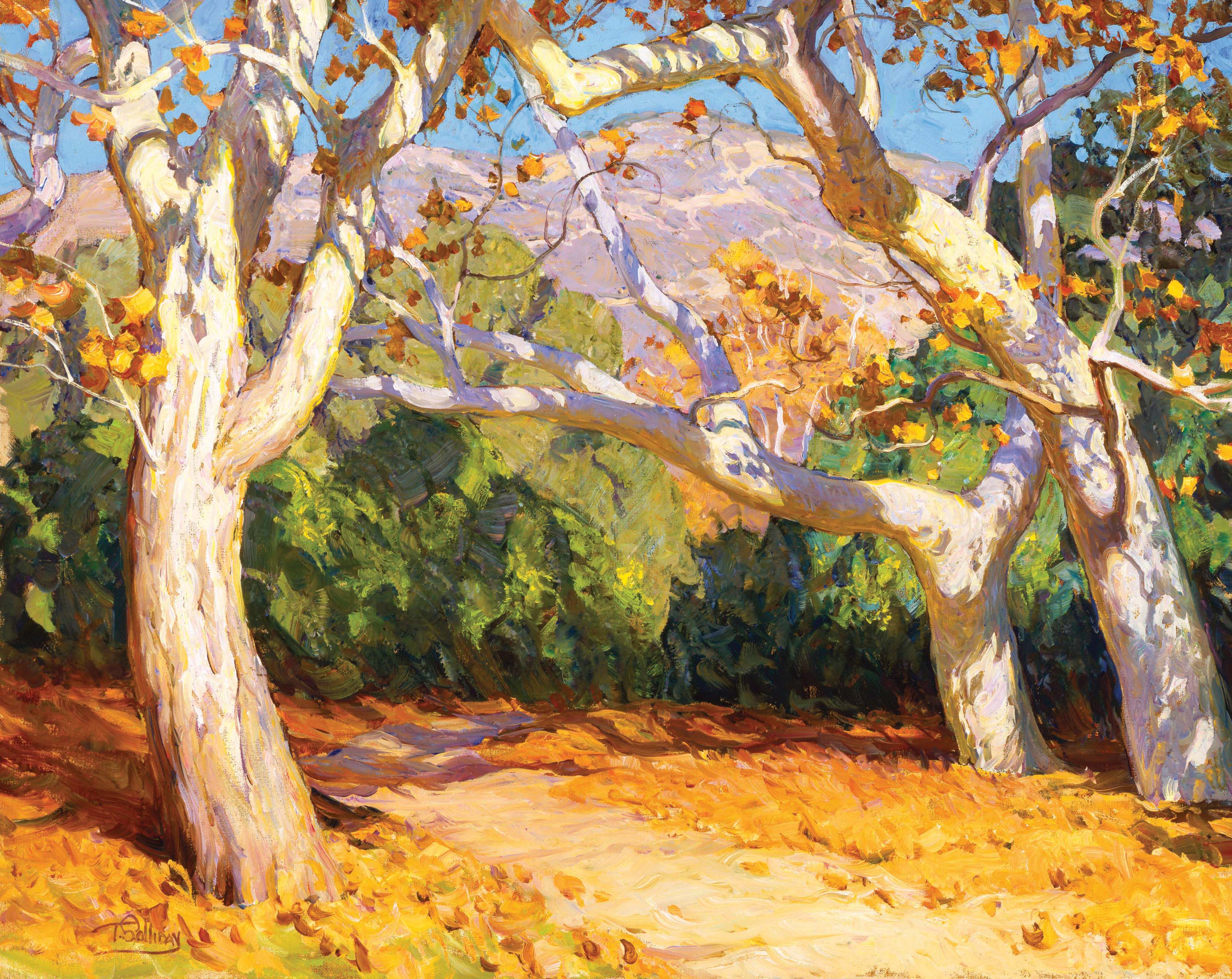

- “Fall Tree” | Oil on Canvas | 18 x 24 inches

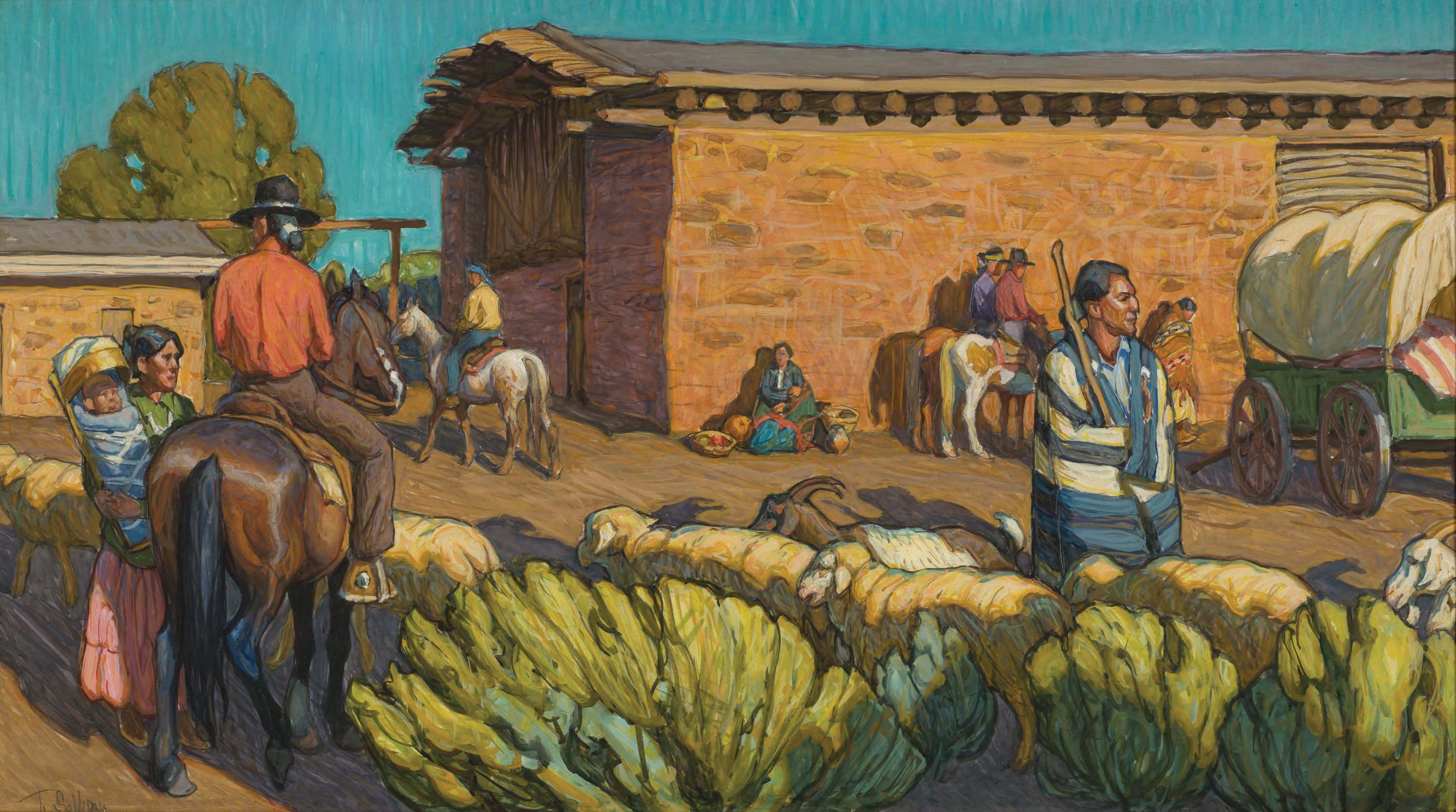

- “Sunset at the Trading Post” | Watercolor and Gouache | 15.5 x 27.5 inches

- “Dinner Guests” | Oil on Canvas | 31 x 57 inches

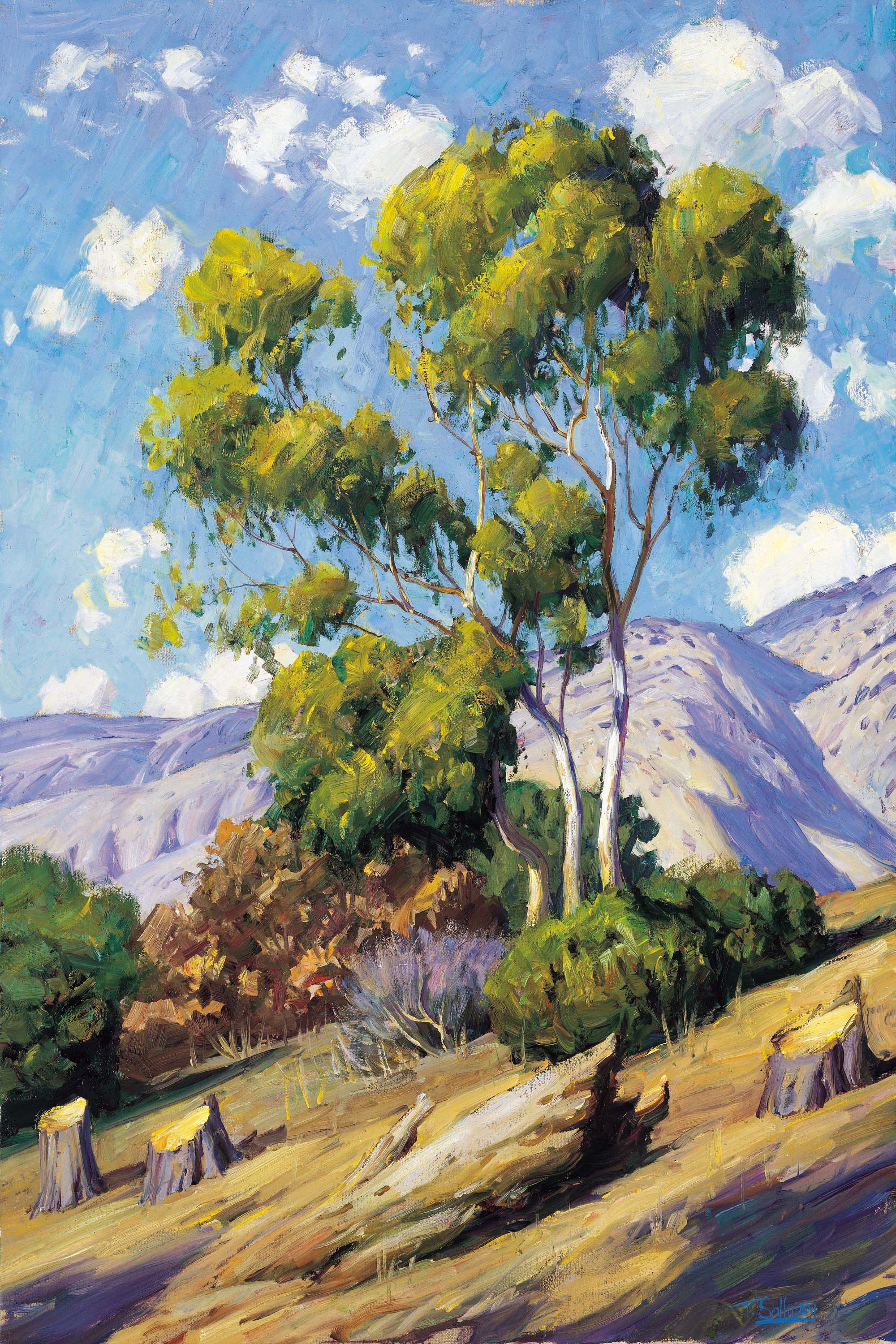

- “Eaton Canyon” | Oil on Canvas | 36 x 24 inches

- “Spirit Song” | A work in progress … painting with sketches | 42 x 60 inches

No Comments