04 Aug A Monumental Talent

IT MAY NOT BE A CAREER PATH appropriate for everyone, but bull riding provided Chris Navarro with many of the tools he needed to become a world-class sculptor.

Bull riders develop an acute understanding of anatomy — both their own and that of the nearly 1-ton beast tucked between their legs. Their sense of movement and motion is akin to a precision dancer, with less room for error. (At least Clara doesn’t have to worry about the Nutcracker Prince stomping her during an unexpected grand jeté.

Most importantly, a bull rider accustomed to counting time in 8-second increments cultivates a vivid awareness of moments, of epic events that happen in a heartbeat.

“Rodeo had taught me how a cowboy feels when his adrenaline is slamming through his veins,” says Navarro in his biography, Chasing the Wind. “It taught me how an animal felt beneath a rider’s chaps. And it taught me about losing and winning and everything in between. I think those lessons have helped me create sculptures that are more realistic and emotional.”

Chris Navarro — who splits his time between Casper, Wyoming and Sedona, Arizona — has been sculpting professionally since 1986. But his artistic journey began seven years earlier. During a visit to the home of sculptor Harry Jackson, Navarro spotted a bronze of a cowboy riding a bucking bronc.

“It was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen,” says Navarro. “It had a beauty and a power to it I just wanted to own. But it was $35,000. I thought if I can’t buy it, I might be able to make one.”

The next day Navarro walked into a Casper art store and announced he wanted to be a sculptor and didn’t know anything about it. Armed with the recommended supplies, he next visited the library where he checked out every sculpting book available.

For several months he spent his days working in the oil fields (he retired from bull riding following a string of injuries) and sculpting at night. His first bronze, a rider atop a spinning bull, won first place in a Cody, Wyoming, art show, netting a $15 prize

and blue ribbon.

Bob Brown has carried Navarro’s sculptures for 25 years at his Big Horn Galleries in Cody and Tubac, Arizona.

“There’s such accuracy to Chris’s work,” says Brown. “Chris knows how a horse moves, how it reacts. He knows the Western way of life, what a cowboy experiences and captures that beautifully. People really respond to that sense of realism combined with the creativity of his ideas. Whenever a new piece from Chris comes in there’s a lot of interest and excitement.”

Today, Navarro is best known for his large bronze sculptures; he has more than 25 monument pieces installed throughout the country.

“The thing about monuments I love is they’re going to be around long after you’re gone,” says Navarro. “It’s going to be kind of a cool thing for all my great-great grandkids to come by and see what old grandpa had to say.”

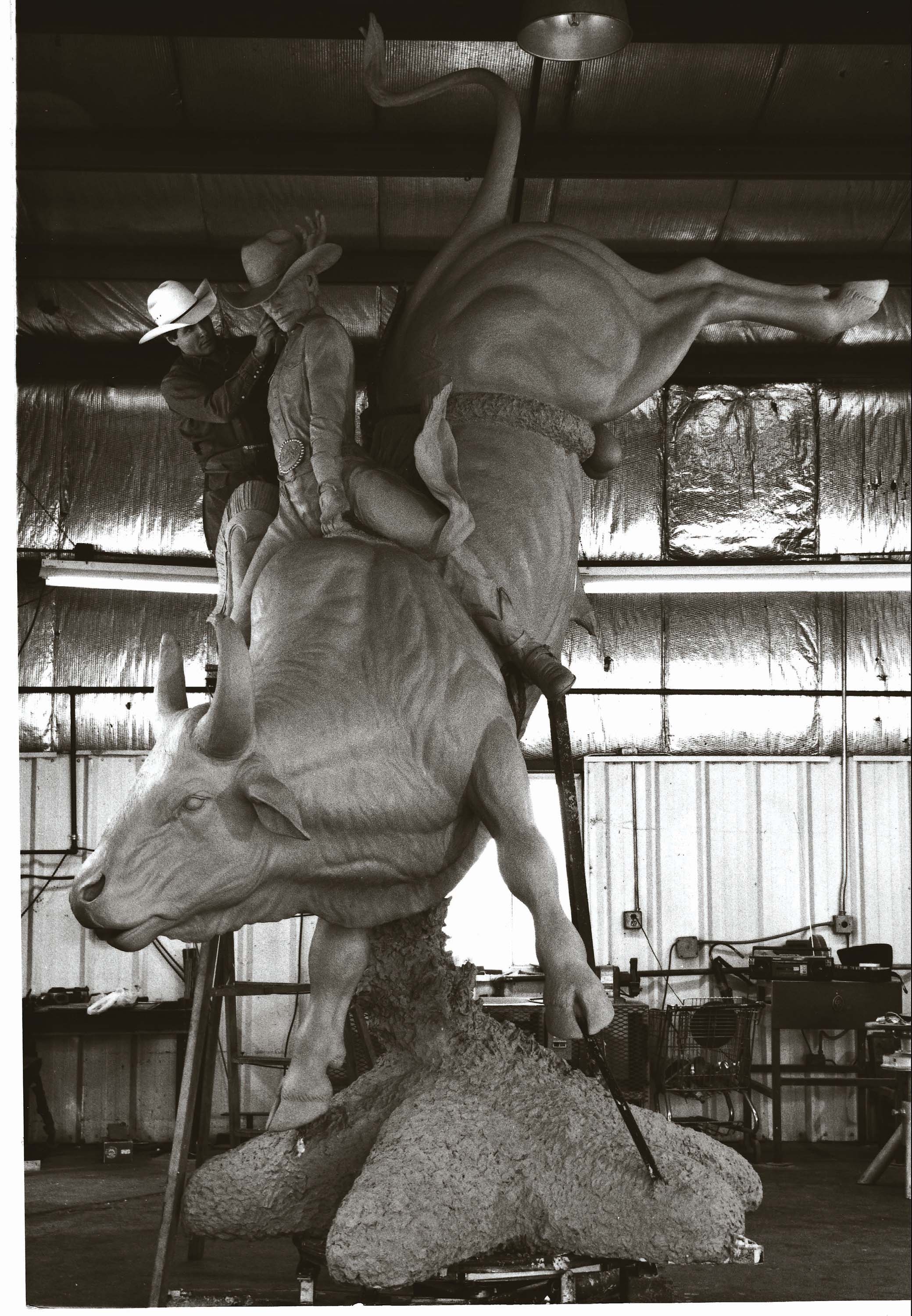

His memorial to bull rider Lane Frost was one of Navarro’s first major pieces and the fact that it was completed at all says a great deal about the artist. Frost, a rodeo legend, died at the age of 25 after being hooked by a bull he’d just dismounted. Navarro decided to honor the fallen champion with a larger-than-life sculpture to stand outside the Frontier Park in Cheyenne, Wyoming. When the organizing committee for the Cheyenne Frontier Days Rodeo was unable to help raise funds for the project, Navarro did it himself, selling bronze maquettes of the memorial. During the project, Navarro’s father suffered a stroke and died.

When the piece was just a week away from being cast, a fire broke out in the studio. Navarro escaped but most of his tools were destroyed, as was the clay surface of the sculpture. Yet later that morning Navarro ordered more clay and sculpting tools. Working long days, he finished the monument in time for the dedication ceremony.

“I think that was a defining moment in my career,” says Navarro. “I wouldn’t quit. All the nos I turned to yesses, it made me feel good about myself.”

Champion Lane Frost remains one of Navarro’s favorite sculptures. The 15-by-11-foot sculpture is an astonishing vertical that somehow conveys an explosive fury mingled with a sense of lingering serenity. Triumph, passion and courage are themes evident throughout Navarro’s diverse collection of works. An unquenchable human spirit roars to life through his deft touch.

“Many of Navarro’s monumental pieces are site specific and this is reflected through Chris’s attention to the way his pieces electrify their environment, not only through appropriate historic subject matter but the dynamic energy inherent to his sculptural technique,” says Aimee Reese, Executive Director of Cheyenne Frontier Days Old West Museum. “It’s a very powerful experience for visitors to arrive at Frontier Park to see the rodeo arena in relation to the Lane Frost sculpture. Many visitors take advantage of a bench located at the base of the sculpture to take time to contemplate. The vision of Lane on the bull with only blue sky as a backdrop is quite beautiful.”

One of Navarro’s more inspirational pieces is called Liberation and was created to raise money for Reach 4 A Star Riding Academy, a therapeutic riding center in Casper. It depicts a young girl mounted without saddle or bridle. She’s riding free and joyful, leaving her wheelchair behind.

“I think there’s something about the magic of horses, that God designed them so they just kind of fit into you and make you feel better about yourself,” says Navarro. “I can’t think of a better program than therapeutic riding, putting handicapped children with horses. It’s why I wanted to create the sculpture.”

No surprise from a man who used to ride rough stock on purpose, but Navarro likes being challenged.

“I never put limits on myself,” says Navarro. “I like doing different kinds of sculptures as long as it’s something that inspires me.”

One of his most famous monuments is the Matthew Shepard memorial. Shepard, a 21-year-old gay man who was beaten to death, hailed from Navarro’s hometown of Casper. Matthew’s mother, Judy Shepard, contacted Navarro who was traveling through Texas at the time.

“That sculpture came to me at four in the morning at an Econo Lodge in Dumas, Texas. I always keep pencil and paper by my bed and I woke up, drew this sculpture, wrote this poem out and went back to sleep. It was the first time a sculpture ever came to me like that.”

Ring of Peace consists of two staggered stainless steel columns supporting a bell that’s circled by nine life-size doves in a swirling crescendo. The poem Navarro wrote is etched on the base of the monument.

“I have the greatest respect and admiration for Chris,” says Judy Shepard. “He is a caring and compassionate human being and an extremely talented artist. I asked Chris if he could create an additional piece based on the memorial that the Matthew Shepard Foundation could present as an award to those who were instrumental in the movement for equal rights for all Americans. He graciously accommodated my request and it is known as the Bell of Peace. I will be forever grateful for Chris and his understanding, accepting heart.”

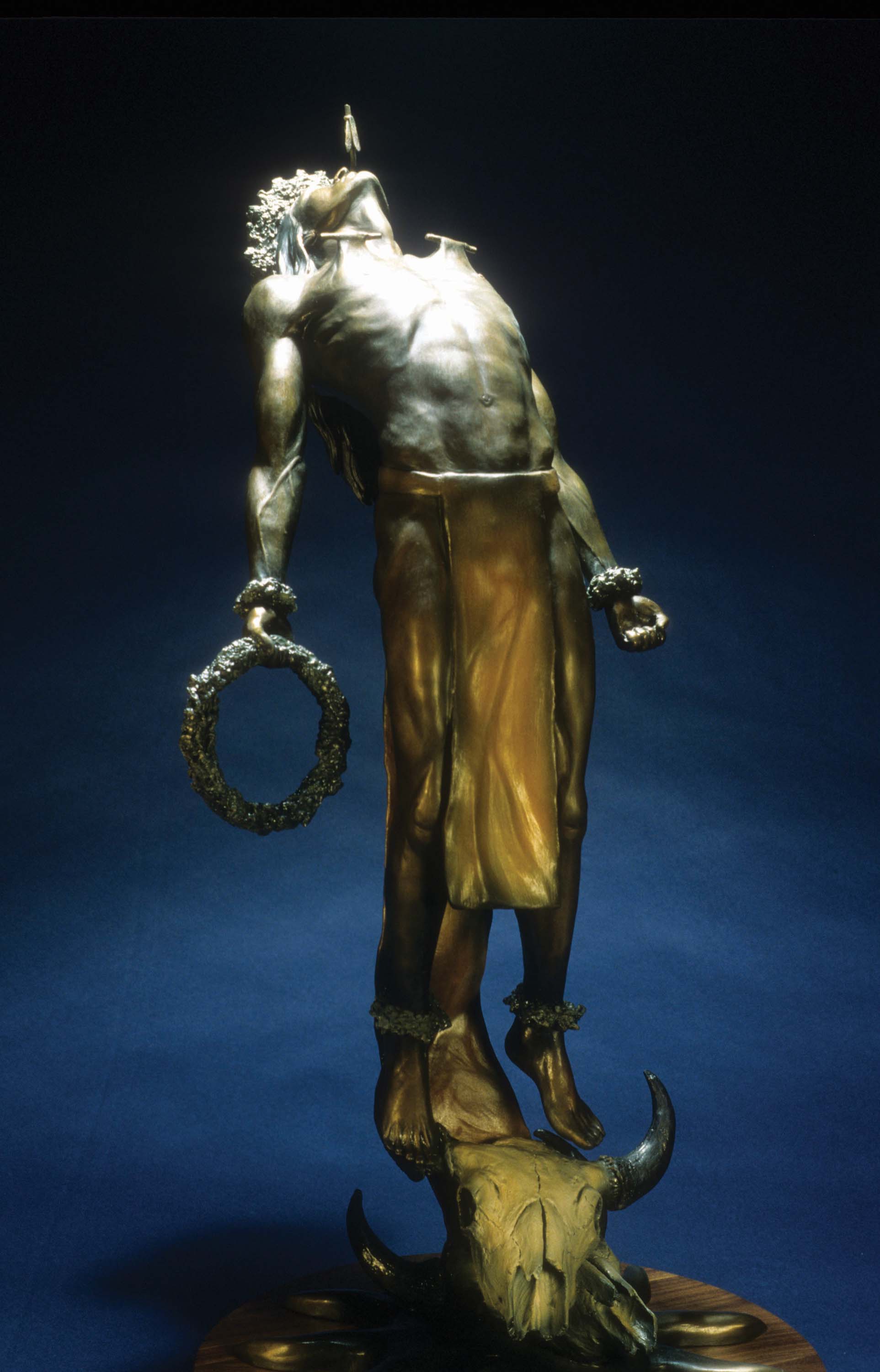

Navarro’s subject matter rises from windswept plains. Lumbering bears, bugling elk and eagles with wind in their feathers. His deep connection to the West reveals itself in numerous sculptures honoring Native Americans such as Spirit of the Thunderbird, an Indian medicine man engaged in ritual dance.

Of course, rodeo remains a subject that will always resonate. While Navarro no longer climbs atop moody bulls, he still competes in team roping events.

“I’m fortunate because I get paid to do something I love,” says Navarro. “The more I do my career, the more I like to loosen up. I like having the aspects of the details in the work, but a good sculpture is a good sculpture before you put any detail in it. It’s all about design and composition and telling a story. And that’s what I try to do with my work is tell a really good story.”

- Columbian Mammoth (20 x 25 x 16 feet), the largest bronze Navarro has ever done, was dedicated in September 2010 at the Washakie Museum in Worland, Wyoming. (Click to expand.)

- “Caballo del Sol” | Bronze | 20 x 16 x 7 inches | 2011

- “Ring of Peace” | Bronze and stainless steel with working bell | 19 x 4.5 x 3.5 feet | 1999

- “Spirit of the Thunderbird” | Bronze | 15 feet

- “Vision Quest of the Sundance” | Bronze | 32 x 14 inches

- Navarro working on “Champion Lane Frost”

No Comments