12 Nov A Way of Seeing

LAURA WILSON IS BLACK AND WHITE ABOUT ARTISTIC IMPETUS. “I photographed what interested me,” she says. “I was drawn to people who live in an enclosed world. I was curious about these groups, and I wanted to know more.” Click.

Fueled by curiosity, Wilson has established her own visual definition of the West through a variety of images that recognize the diversity of distinct cultures across the region. Her work captures the beauty, but also the bleakness, that often exists in tandem in the West.

“I’m not interested in the landscape in the way that great landscape photographers are,” she says. “And I’m not interested in speaking so much about the environment the way other great photographers have been. All of that is important work, but it’s the people that interest me — the conditions under which they live, trying to cope and work. The West has a purchase on our collective national imagination, and so I think that’s interesting.”

Wilson’s work in the West is the subject of a retrospective exhibition at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas. The exhibition, Laura Wilson: That Day, includes 71 photographs — some of which ran in The New Yorker, Vanity Fair and The New York Times Magazine, among others — and runs from September 5 through February 14, 2016. The show’s title reflects the photojournalistic immediacy of Wilson’s work and nods to the way she frequently starts a story about something she saw with the phrase, “That day … ”

Dr. John Rohrbach, senior curator of photographs at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, says the exhibit will draw in visitors to a particular moment. “Photography tries to present the world to us in a way that stops us, challenges us and makes us want to come back and reconsider our own lives,” says Rohrbach. “Laura does that really beautifully.”

While Wilson’s work is rooted in a very recognizable Western tradition, Rohrbach explains, it twists expectation. “Some of the images are really beautiful, engaging and luscious — like the young girls just before their first communion,” he says. “But some images are harder, and it’s that variety in combination that tells a larger story about the West and makes her work important.”

Wilson, who lives in Dallas, looks at photography as a way of seeing and, more importantly, as a way of engaging in the world. “I think you can’t be interested in pictures in the West without being interested in the problems of the West: border issues and immigration; pit bull fighting; and the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation [in South Dakota], where there is generational poverty, dysfunction in tribal government and families, and terrible alcoholism. If we aren’t willing to look at these problems, how are we ever going to be able to solve them?” she asks. “There are so many issues to be concerned about, and photography can deal with them, in a way.”

Wilson’s drive shows up in her fifth book as both images and words. A companion book to the exhibition, That Day: Pictures in the American West, was published in September and designed by art director Gregory Wakabayashi. “Laura provides some information about the subjects of her photographs, but also intertwines that with her own personal experience of photographing them and documenting them, expressing her connection to it from a personal level,” says Wakabayashi, who has worked with the photographer for more than 15 years. “It’s the balance of the two that is very much a foundational part of the experience of her work in this book.”

Wilson’s interest in photography began as a child when she became enamored with photographs of her mother taken before Wilson was born. An uncle gave her her first camera when she was about 10 years old. But it wasn’t until she had children of her own (her sons are actors Andrew, Owen and Luke) that Wilson — who studied English literature, painting and studio art in college — got serious about photography. “When my children were born I realized I didn’t have time to paint, whereas a camera was more immediate. The snapshot is completely responsive to family life,” Wilson says. “I like the idea of trying to stop the passage of time with photography.”

Wilson never took a photography course. Instead, she learned her craft the old-fashioned way, studying as an apprentice for six years, starting in 1979, under Richard Avedon, one of the most prominent American photographers of the 20th century.

“To work with one of the great photographers in the history of the medium was completely transforming,” Wilson says of the working relationship with Avedon that spanned 25 years until his death in 2004. “Not so much in knowing about f-stops and shutter speeds, but in knowing what it means to take a strong picture, what it means to take a picture or look for the photograph that will ‘hold the wall,’ that will be memorable.”

With her new retrospective, more than 35 years of work under her belt, and the constant forward momentum created by curiosity and compassion, Laura Wilson is making pictures that will always hold the wall.

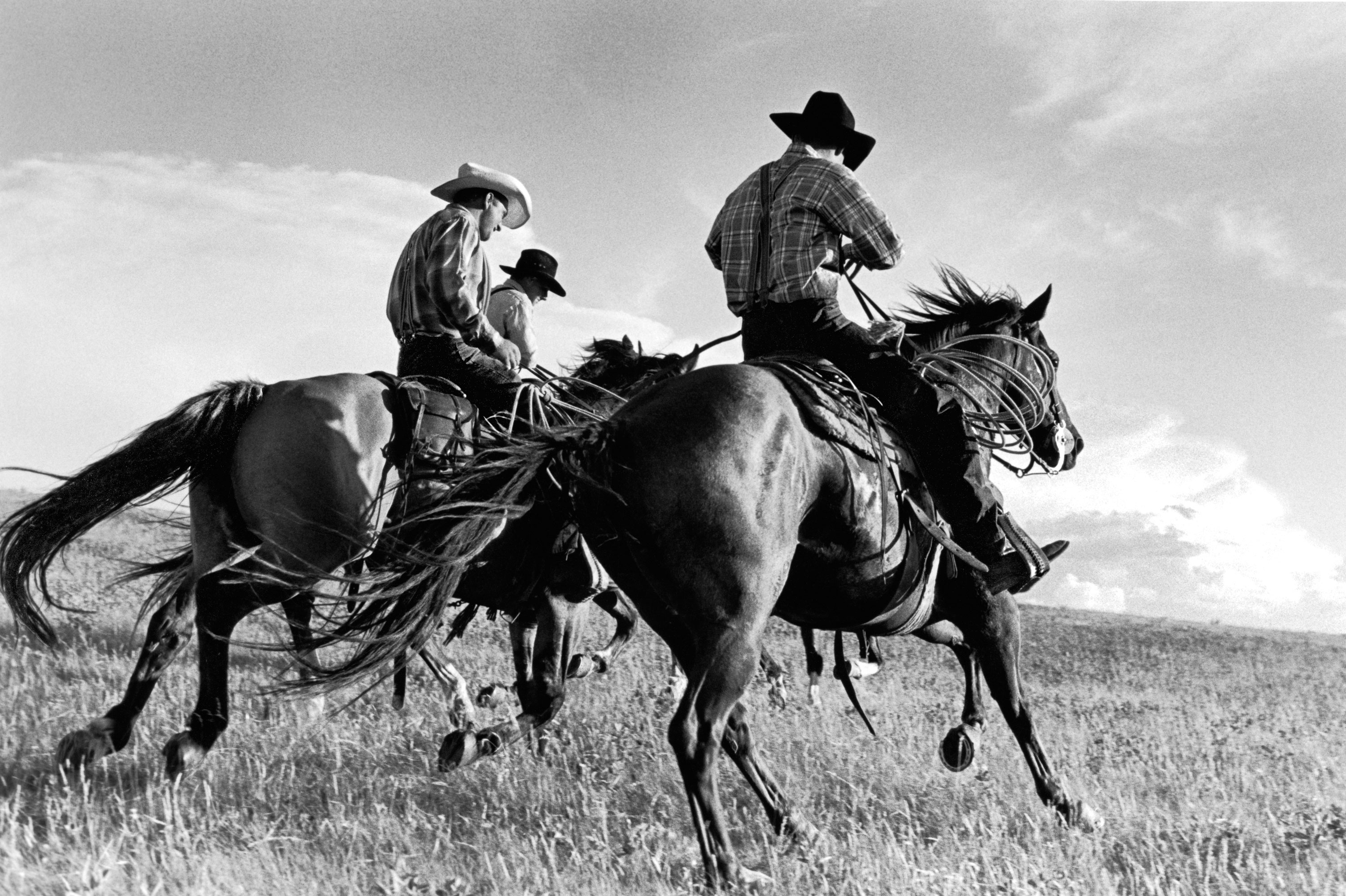

- “Hutterite Cowboys Galloping” | Surprise Creek Colony | Stanford, Montana | July 12, 1996 | “These Hutterites boys are two brothers and one cousin out for an afternoon gallop in their own backyard.”

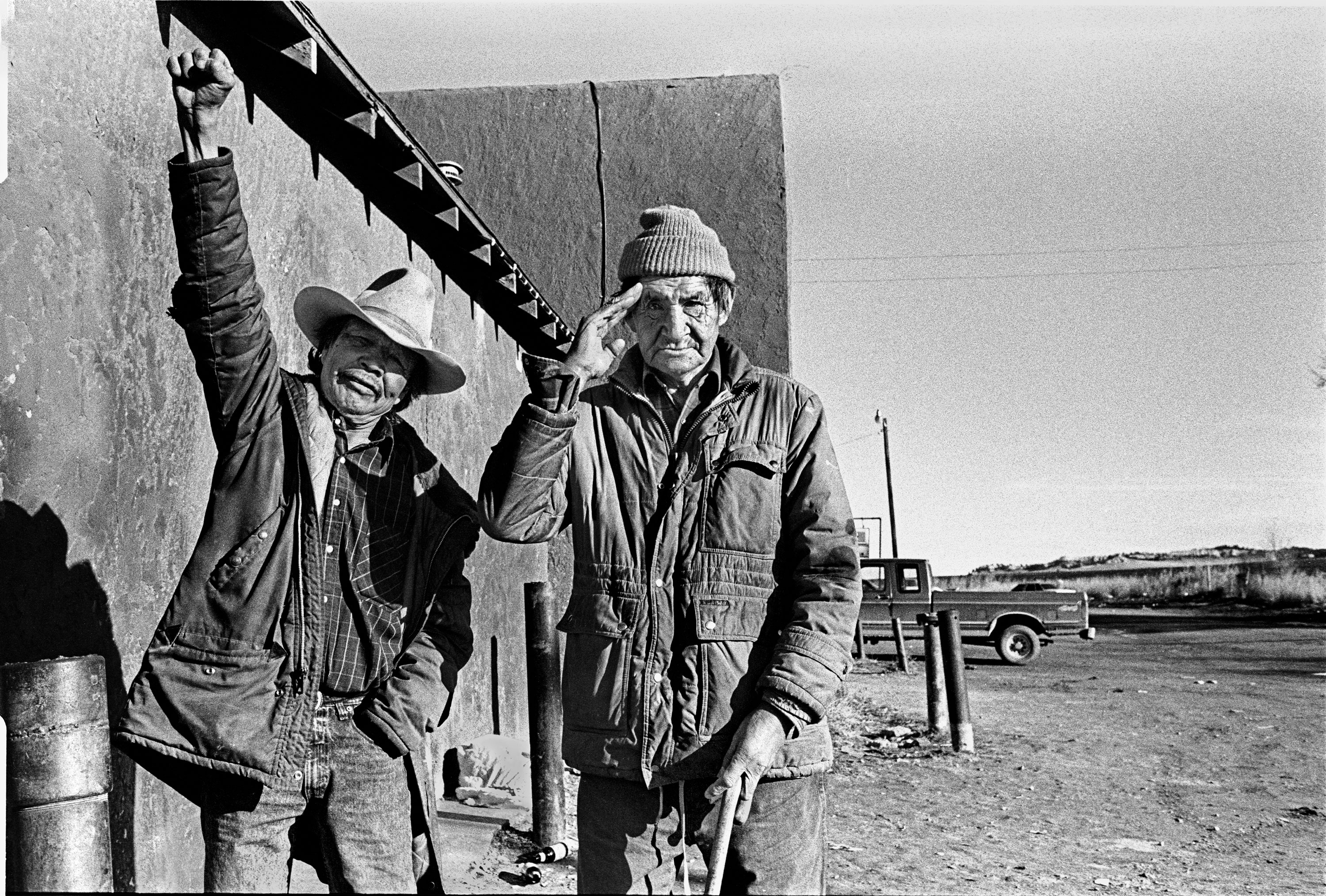

- “Two Oglala Sioux Men” | Whiteclay, Nebraska | December 13, 1996 | “Although the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota bans the sale of liquor, its population is plagued by alcohol problems. Seventeen miles to the south, the neighboring town of Whiteclay, Nebraska, has four liquor stores that sell a staggering amount of alcohol to residents of the reservation each day.”

- “Cock Fighting Spurs” | Webb County, Texas | May 12, 1994 | “Cockfighting is an illegal and vicious sport that is thriving among tight-knit groups of people in Texas and Oklahoma. Two roosters, bred for the ring, are fitted with razor sharp steel gaffs designed to slice, puncture and mutilate. It is now against the law to own birds with the intent to fight them.”

- “First Communion” | Dallas, Texas | May 16, 1993 | “First Communion is a solemn and important occasion for all Catholics. The event is of such importance that Mexican families have an expression, ‘Tu quieres tirar la casa por la ventana!’ (You want to throw the house out the window!), to justify break-the-bank spending.”

- “Hutterite Women Gardeners” | Riverview Colony | Chester, Montana | June 22, 1994 | “In an America that has largely abandoned its agrarian heritage, the Hutterites have held on to the land. They operate substantial farms and ranches and share all property and income equally.”

- “Hand and Spur” | Y-6 Ranch | Valentine, Texas | June 3, 1992 | “Ranching is a hard way to make a living. The margin of profit on cattle is so slim that ranchers can barely hold on to land that they’ve worked for generations to put together. Yet the land has a grip on them.”

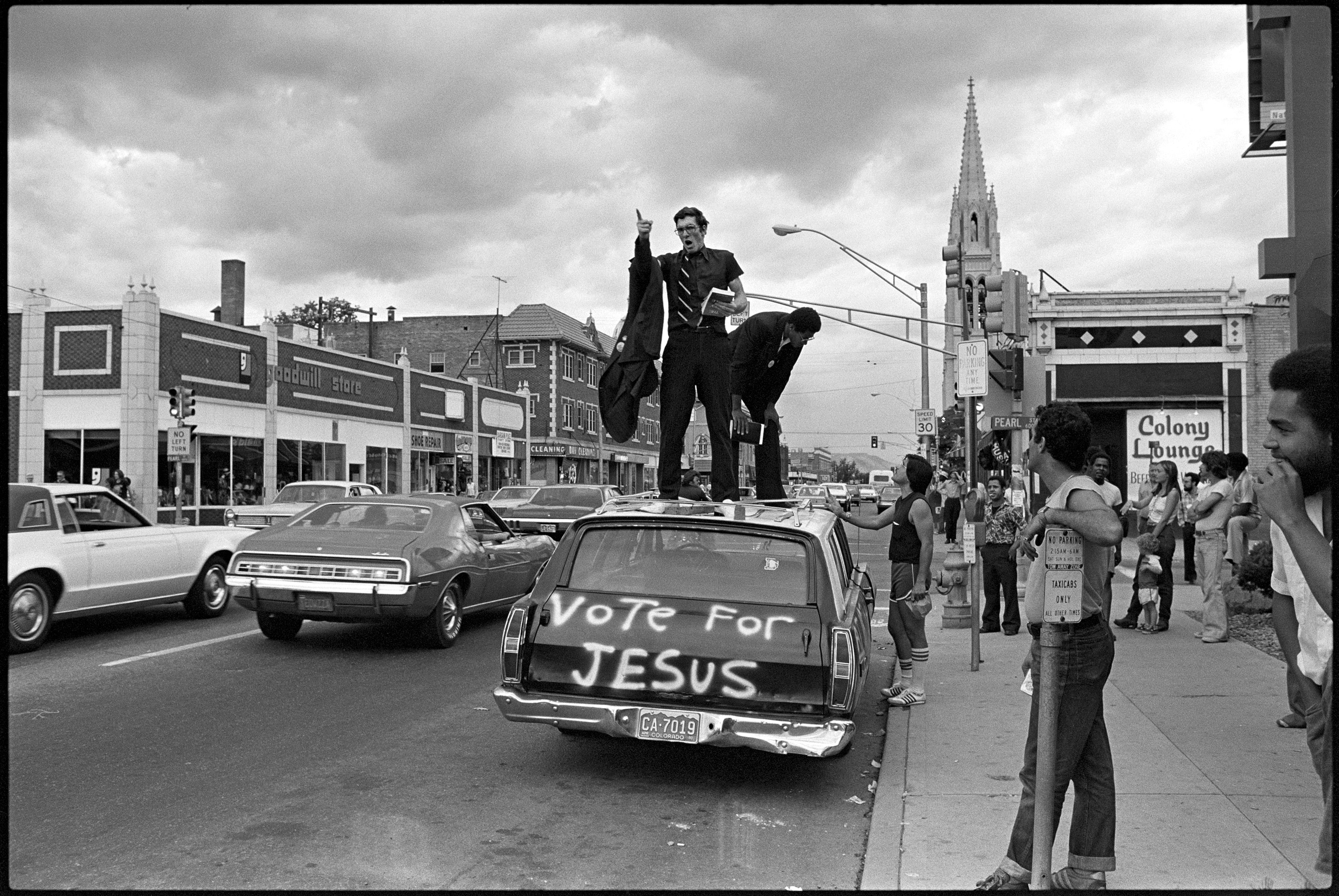

- “Evangelical Preacher” | Denver, Colorado | August 19, 1980 | “On my drives across the West over the past 15 years, I’ve noticed a significant growth of Evangelical and Pentecostal groups. The number of small places of worship has seemed to triple as the fundamentalist Christian frontier expands.”

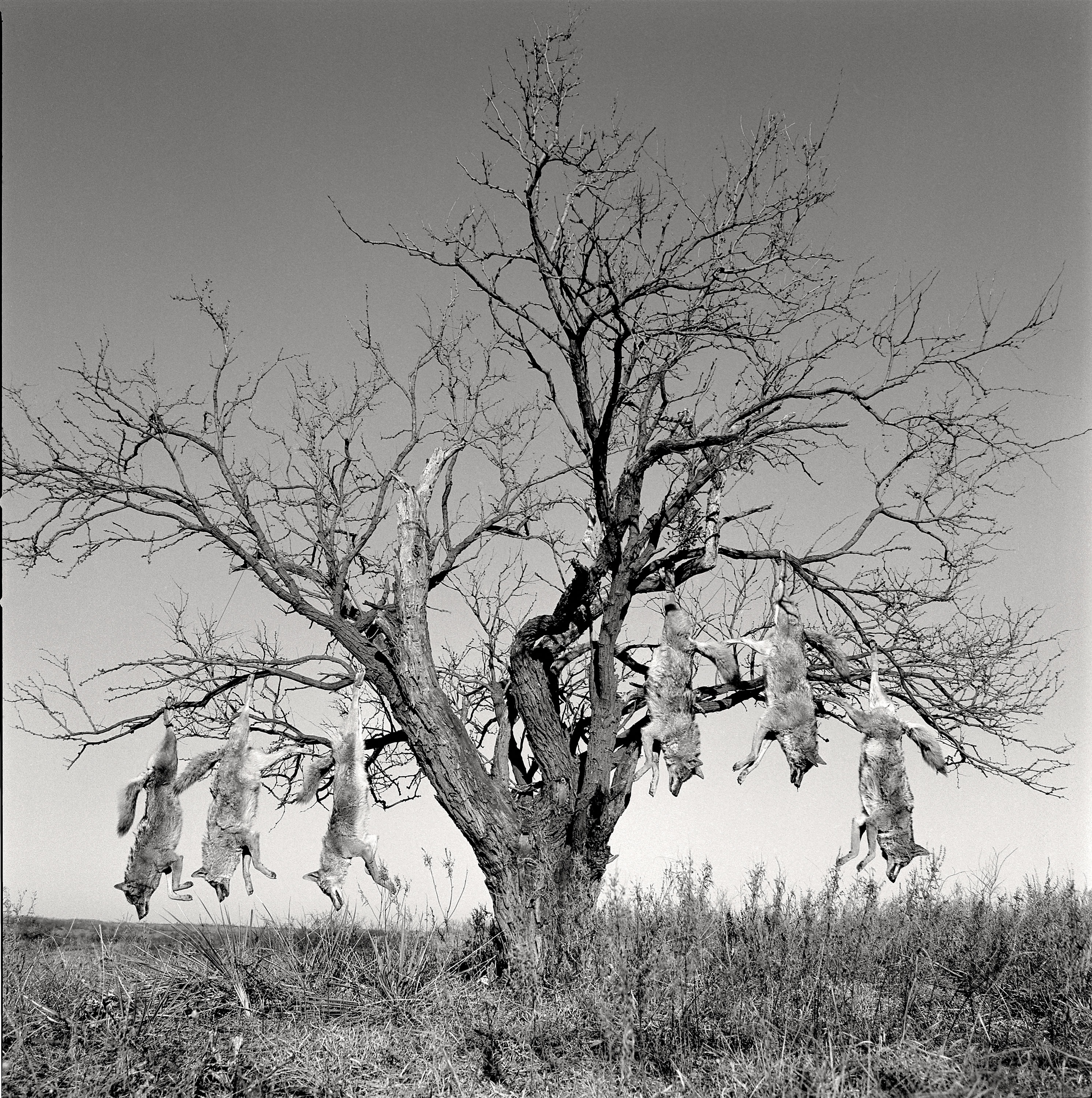

- “Mesquite Tree with Coyotes” | Lambshead Ranch | Albany, Texas | January 9, 1988 | “Coyotes have just one serious enemy: man. On rangeland all over the West, ranchers and farmers have coyotes forever in their gunsights. Once killed, they are hung up to bleed out before their hides are taken in for a bounty.”

No Comments