19 Oct The Woolaroc Rises Again

MANY A FINE ART MUSEUM WOULD CONSIDER IT A MARKETING COUP to be labeled “one of America’s best-kept secrets.” But from his vantage in the pastoral Osage Hills of Oklahoma, Bob Fraser has heard the sentiment expressed so many times that he no longer embraces it as a compliment; instead, he and a determined group of Sooners are now aiming for a remedy.

“We’re not aspiring to be anybody’s best-kept secret,” he says. “We want to reclaim our place on the art map of the West. For adventurous people who think they’ve seen it all, we want to be known as their next great discovery.”

Mr. Fraser’s institution, the sprawling Woolaroc Museum & Wildlife Preserve near Bartlesville, has plenty of ammunition to make a compelling case. In 2013, fresh off the completion of a major facelift in its distinctive gallery spaces, Woolaroc is hosting a retrospective based upon pieces pulled from its own jaw-dropping collection. In addition, it is unveiling an exhibition of contemporary paintings by Charles Fritz and sculpture by Richard Greeves focused on their interpretations of the Lewis and Clark expedition.

Indisputable — though it has indeed existed as a diamond in the rough — the Woolaroc has, for its size, one of the most striking collections of Western art and Native American artifacts in the country. Brimming with rustic charm, it’s also a site, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, that arguably boasts one of the most colorful backstories of any art destination in the U.S.

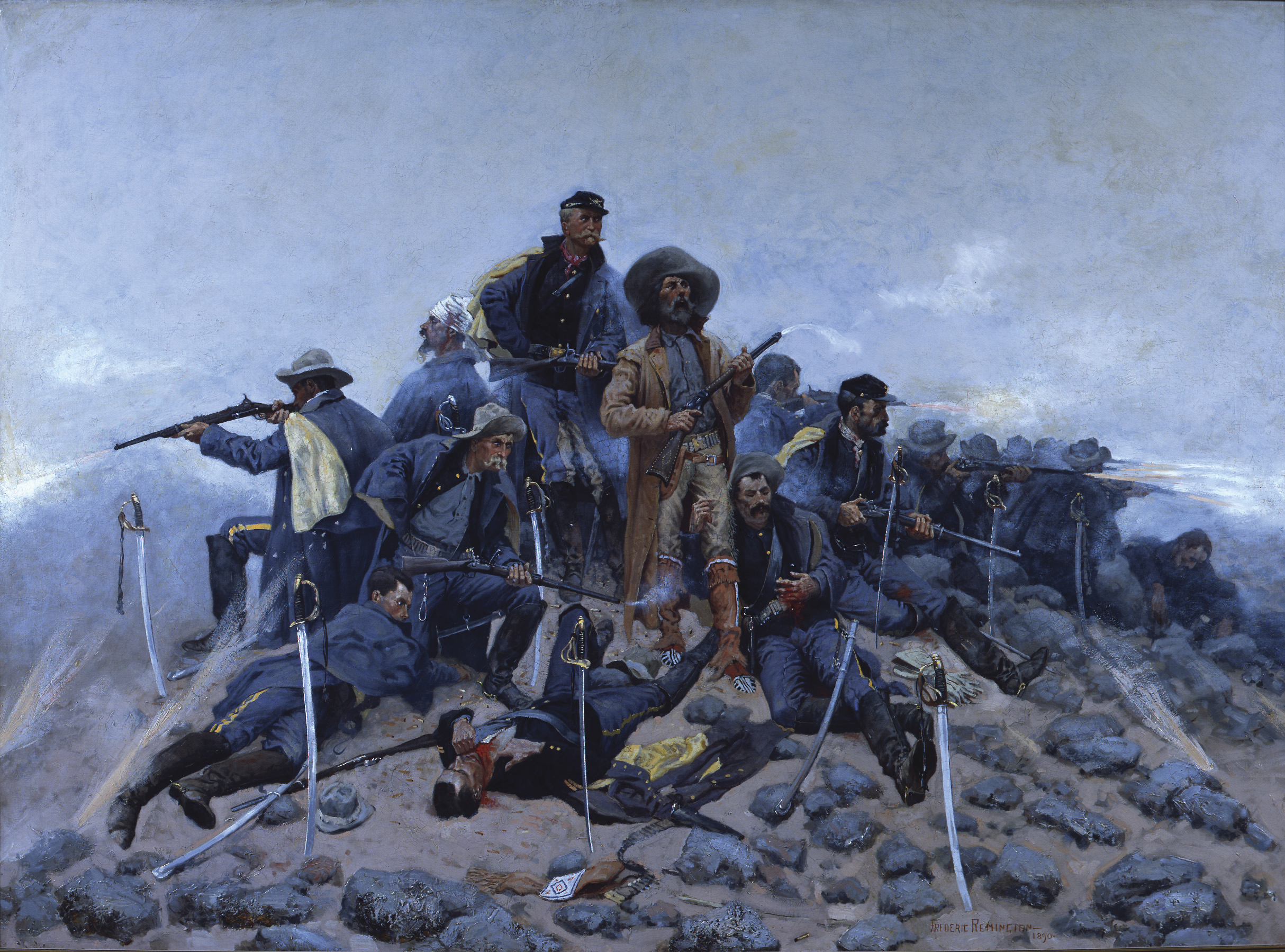

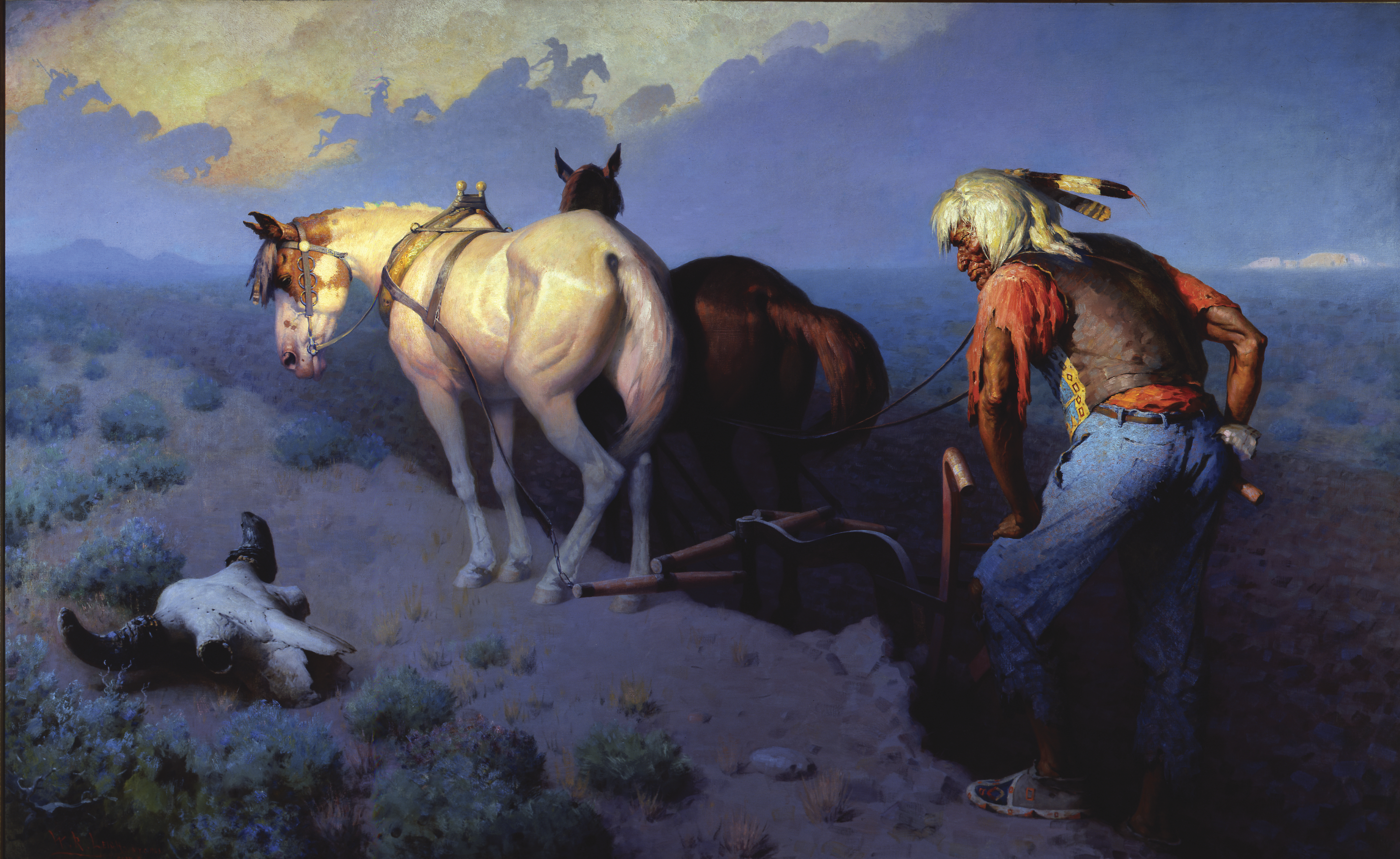

How many museums boast a treasure trove of W.R. Leighs, Frank Tenney Johnsons and Charles M. Russells? A portrayal of Custer’s Last Stand by Frederic Remington, landscapes by Thomas Moran and works by five of the original six Taos artists? Or a series of 27 miniature bronzes celebrating pioneer women that were part of an international competition? A bevy of Native American pottery and ornamental headdresses and attire from 40 different tribes? How about a rare First Phase Navajo chief blanket and a vintage firearms collection (including guns by Colt and Remington Arms)? And all of this surrounded by a panorama of living, breathing herds of plains bison and longhorns.

Not long ago, Marc Porter, president of Christie’s Americas took a tour and proclaimed it “one of the most magnificent Southwest art collections in the country.”

Established by oil tycoon Frank Phillips (founder of Phillips Petroleum Co.) and his wife, Jane, as a personal Shangri-la in 1925, Woolaroc is an important — though largely unsung — landmark in American art history. Some 20 years ago when I paid my first visit, I was inspired by the words of a friend, Oklahoma native son William Kerr, founder of the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

Kerr said simply: “If you love art and Western culture and history, young man, then part of your education involves a requisite stop at Woolaroc. I’m not gonna tell you much more than that, but I have a hunch you might find it unforgettable.”

Over the past two decades, I’ve been back to the museum four times.

As a name, “Woolaroc” is actually a portmanteau inspired by the terrain that engulfs the ranch — woods, lakes and rocks. During its heyday, Woolaroc was known for its annual party in which the guest list included famous politicians and celebrities as well as outlaws on the lam. The only condition was that everyone had to check their guns at the door. (Those trying to stay ahead of the posse were, with the consent of local deputies, given a head start after the last drinks were poured).

Scores of influential figures graced Woolaroc, from a man destined to become president of the United States (Harry S. Truman) to Blackstone The Magician to Okie cowboy and humorist Will Rogers. Of the Woolaroc, Rogers remarked (presaging Kerr’s assessment 50 years later): “It’s a place like no other in the world.”

Phillips’ rise is the stuff of legend. As man of humble beginnings, he transformed bets placed on a few wildcat wells into a fortune when they became gushers. He saw the last residue of a wilder West hanging in the air during his early adulthood and spent decades creating an escape intended to summon reflection on Indian and settler culture. Going by the nickname “Uncle Frank,” he believed the richest life was one spent with friends in the great outdoors and not stuck inside a Gilded Age mansion.

Both Phillips and his wife collected art and decorated Woolaroc with pieces that reflected a West before it was tamed. Their vision is still vivid in the house. What began as a simple cabin overlooking the fish-filled waters of Clyde Lake would steadily morph into one of the quintessential examples of Great Lodge design. (Modern architects routinely make visits to Woolaroc to glean ideas for client projects).

Today, the lodge’s Great Room rotunda, decorated with mounted heads and horns, functions as a staging area for visitors who can literally spend hours exploring the massive collection that is displayed in a half-dozen gallery spaces (formerly sleeping quarters for family and guests).

Nearby, a short stroll away, is the original stone pavilion that Phillips built to house his monoplane, also named Woolaroc. In 1927, just months after Charles Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic, Phillips’ craft won a race from Oakland, California, to Honolulu, Hawaii.

Beyond the pavilion and past a scattershot of other structures, much of the 3,700 acres serve as a wildlife preserve for native and exotic species where visitors can picnic or loll on the southern prairie.

Woolaroc trustee Dean Zervas was born in Pawhuska and raised in Bartlesville. “Woolaroc was part of my identity growing up, just as it is for a lot of people in northeastern Oklahoma,” he says. “And now, to actually be carrying on Frank Phillips’ legacy is an amazing thing for me. We want to bring Woolaroc into a new era.”

Zervas says that he and his fellow trustees were well aware of a challenge becoming ever more acute in recent decades — how to reconcile Woolaroc’s semi-primitive character with it being a repository for extraordinary art.

The Native American pieces are considered priceless. And along with the master artists mentioned above, there are significant Western works by O.E. Berninghaus, Herbert Dunton, E.I. Couse, Bert Phillips, J.H. Sharp and more contemporary talents such as Wilson Hurley, John Clymer, Bettina Steinke and Clark Hulings.

“Some people refer to it as an eclectic collection because in addition to art and artifacts there are things that were picked up in travels around the world — including the famous Peruvian shrunken heads that all school kids remember,” Fraser says. “We don’t judge. Uncle Frank collected what he liked.”

Were Woolaroc situated in a large city, there can be no doubt that its annual visitation would number in the millions. Only a fraction of that finds its way into the Osage Hills. Ironically, it was the Phillips’ quest to achieve tranquility in the Oklahoma countryside, far off the beaten path of the modern world, that has led to the Woolaroc struggling to overcome isolation and raise its rather obscure profile.

Another aspect is the heady company it keeps in Oklahoma. For decades the Woolaroc has dwelled in the shadows of three other Western art pillars: The National Cowboy & Western Heritage Center in Oklahoma City (host each summer to the Prix de West Invitational art competition), and the Thomas Gilcrease and Philbrook museums 45 minutes down the road in Tulsa.

For help in confronting the dilemma, the Woolaroc trustees turned to a Western art heavyweight living in Los Angeles. Zervas and the board knew of John Geraghty’s reputation for curating a number of prominent art shows, including the Autry Museum’s annual Masters of the American West exhibition. Many, in fact, credit Geraghty, as a trustee, with transforming the Autry from a regional art center into a national powerhouse.

“They were looking for some way to elevate the museum’s profile,” Geraghty says, noting that he hadn’t been to Woolaroc in 20 years. The last time was when Joe Beeler unveiled a monumental bronze on the grounds. “I knew they had some wonderful art, but it sort of got lost in the way it was presented.”

It was a point not lost on Fraser and his board. Much of the interior gallery lighting system at Woolaroc hadn’t been updated in more than a generation. Plus, the walls were showing their age.

The trustees asked Geraghty for suggestions on how to stage an event that would generate a buzz. At that point, he dispensed some tough love. His advice: Woolaroc should remind the public what it has by mounting a retrospective showcasing the world-class gems in its collection.

“However, I also told them that they could stage the best retrospective in the world, but it wouldn’t accomplish what they wanted if people came to see the show and remembered only the exhibition and not much about the museum. They needed to make some investments in art presentation. ”

Slowly, room by room, the Woolaroc started a few years ago on a restoration that is still ongoing, being completed as the budget allows. As news of its renovation spread via word of mouth, small checks from people who had grown up going to the ranch began arriving in the mail.

“It’s been heartening to know that Woolaroc has a group of loyal fans all across the country who have maintained that special connection,” Fraser says. “Their contributions have enabled us to move forward. Of course, we’d be eternally grateful if a couple of benefactors stepped forward and enabled us to get everything done sooner.”

Zervas says the improvements will serve as a springboard for Woolaroc unveiling an unprecedented “re-staging” of its collection in 2013. “I think it’s exciting. It’s almost like a new museum is rising,” Geraghty says. “When people walk through the front door into the rotunda and are confronted with those Leighs or Russells, they’re going to be knocked to their knees with awe.”

Zervas and Fraser say the museum has had to strike a delicate balance between preserving Woolaroc’s rough-hewn charm and doing the collection justice. Phillips, they note, would have been offended if the Woolaroc ever traded in its atmosphere for stuffier airs.

“By design, it isn’t pretentious and that’s how ‘Uncle Frank’ wanted it. He thought art and history should be accessible,” Zervas says. “He wanted Woolaroc to be welcoming to people no matter who you are or what your walk of life is.”

Today, the spirit of Frank and Jane Phillips endures. The couple is buried on the property in the family mausoleum. “They thought this was the most beautiful place in the world — it’s a physical setting to match the art,” Fraser says. “We hope the gift they gave to promote appreciation for American art and history doesn’t remain a secret any longer. If you can get here, I know you’ll be pleasantly surprised.”

- Material from approximately 40 tribes is displayed in the Woolaroc, including here, in the main gallery.

- The ranch and the Woolaroc Lodge were the place where every element of the local culture could gather and feel welcome.

- Frank and Jane Phillips founded the Woolaroc Museum on their ranch in 1929, modestly and almost unwittingly, as an open-air stone pavilion to house Frank’s beloved airplane.

- The Woolaroc collection includes a broad representation of paintings by many of the “Old Masters” of Western art. Shown here: Frederic Remington’s “The Last Stand”

- The Woolaroc collection includes a broad representation of paintings by many of the “Old Masters” of Western art. Shown here: William R. Leigh’s “Visions of Yesterday”

- Much of the fine art collection was personally acquired by Frank Phillips during his lifetime, including “When Meat Was Plenty” by C.M. Russell.

No Comments