30 May Christopher Blossom's Ship Comes In

SAILS FILLED AT FULL BLOW, the good ship Benjamin F. Packard pitches and yaws, charging toward shelter in San Francisco Bay. From halyards and baggywrinkle to bowsprit and transom — the tack of the water steed — every nuance of her history is insinuated.

Yet it is the spirit of the 1883 clipper, unshackled from exacting detail, that the viewer feels as she moves dreambound to port.

Far from the dust of a rodeo ring, Indian pueblo or vaulting jawlines of the Rockies, this vision, too, is an important visual aspect of the American West. The nautical tradition encompasses galleons of Spanish conquistadors, exploratory British flagships, cutters carrying Asian laborers to build the transcontinental railroad and vessels ferrying gold miners north to the Klondike a la Jack London.

In Christopher Blossom’s capable hands, a scene rings truthful not only for its authenticity, but by execution his oils share company with some of the great narrative paintings in fine art. “Chris’ wonderfully unique marine paintings are as much a portal into the development of the American West as a Moran, Russell or Remington, but from the perspective of the sea,” says Blossom’s friend and artistic colleague, James Morgan, who calls Utah home. “Without shipping, the West would not have settled the same.”

Blossom, a soft-spoken Connecticut Yankee and lifelong mariner, has devoted innumerable moments to thinking about timelessness and tradition on the liquid horizon. Indeed, it flashes winsomely in Sunrise in the Golden Gate; Downeaster Benjamin F. Packard, 2010 winner of the prestigious Prix de West Invitational Purchase Award presented by the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. And it added another layer to how the West is being re-imagined in the 21st century.

What Blossom plans as an encore is being met with high expectations. While some say winning Prix de West marked his formal arrival in the pantheon of contemporary Western artists, friends like Morgan say it only confirms a talent that the painter has demonstrated for years in his forays across the inner continent of North America and Europe. Blossom is, by his own admission, a modern Romantic Realist.

After exhibiting at the Salmagundi Club in New York City, and returning to Prix de West, Blossom will join Clyde Aspevig, George Carlson, Len Chmiel, Tucker Smith and Daniel Warren Pinkham this summer in Wyoming. The August exhibition at the Jackson Hole Center for the Arts is being billed as one of the artistic highlights of the year, for it features six masters of plein air and studio, each operating at the height of their interpretive powers.

My first encounter with the well-traveled Blossom happened years ago as he stood over a soothing sheen of blue-green water, squeezing earth tones onto a portable palette. Topographically speaking, “the American maritime artist” whom many have dubbed the greatest of his generation, was 1,000 miles removed from the sea.

Camped with Smith and Morgan, they had horse-packed into the Wind River Mountains of Wyoming, retracing a path to Vista Lake taken by Carl Rungius nearly a century earlier. It has become an annual ritual for fellow Prix de West winner Smith, who lives on a ranch in nearby Daniel at the foot of the Winds, to share his savored backyard haunts with those who also savor similar ambient sensibilities.

On that day, Blossom sketched in graphite, ginned up thumbnails and then added to a growing stack of field studies. When the whitecapped summits rose on his French easel, his interpretations of natural architecture were as regal as the masts of tall ships — his portrayals of the latter having earned him comparisons to legendary Englishmen John Stobart and Montague Dawson.

“His art is the way he processes the world, and his paintings are like he is, loaded with creative intelligence, but very lean, with no fat,” says J. Russell Jinishian, owner of an eponymous gallery in Fairfield, Connecticut.

Jinishian has represented Blossom’s work for 30 years and the two are frequent sailing partners. He knows how Blossom has been wooed by the West. “If you talk with his contemporaries, who are skilled in the sophisticated technical decisions painters make, Chris is the one they look to,” Jinishian notes. “He’s always searching for a new way of seeing something fresh, whether it’s a slice of history or a point of geography.”

Born in 1956, Blossom is the son and grandson of two well-known painters and commercial illustrators. He grew up around artistic members of the “Connecticut Mafia,” many of whom eventually fanned out across the West and left their marks as easel painters.

After graduating from the Parsons School of Design, Blossom himself had a brief stint in illustration, then worked in the Industrial Design Studio of Robert Bourke producing high-end architectural blueprints.

For sure, his gravitation to nautical subjects is an extension of painting not only what one loves, but also what one knows. Instincts and artistic knowledge were absorbed as he sketched beside his father in the studio and their bond was made even tighter by their time sailing together. David Blossom (1927 – 1995) painted and worked as art director at a New York advertising firm not altogether different from the one featured on the TV series, “Mad Men.”

Chris Blossom was influenced early, he says, by studying some of the giants in the Golden Age of Illustration, namely the master of dramatic scenes, Howard Pyle, and his protégées, N.C. Wyeth and Dean Cornwell, and the lineage that followed. “I particularly liked the design of their pictures, and how they chose their narrative moments, not always the most obvious, but often filled with the potential of all sorts: impending storms, imminent violence, silent contemplation,” he says.

Of course, any story about a contemporary maritime painter would be incomplete without mentioning Stobart, who resettled in America and is regarded as the dean of the genre. Blossom’s father introduced his son to Stobart when the boy was not yet a teenager. They became friends. It was not uncommon for them to stop by Stobart’s studio and see what he was working on.

From that foundation, Blossom became affected by others — John Singer Sargent, Joaquin Sorolla and Anders Zorn, and Russian Isaak Levitan — after he left Parsons. Famously, Levitan once observed, “What can be more tragic than to feel the boundlessness of the surrounding beauty and to be able to see in it its underlying mystery … and yet to be aware of your own inability to express these large feelings.”

Blossom’s work does not stand accused of suffering from repressed passion, though his play on nostalgia is not sentimental. While he reveres the Europeans, he finds a greater kinship with American Impressionists who exerted their own distinct style of interpretation.

“Without a doubt illustration was good discipline, and because the deadlines forced quicker decisions, perhaps it forced a quicker learning curve by generating a lot of work in a shorter time,” Blossom reflects, in particular reference to his plein air work. “Nonetheless, I think the lessons are the same no matter what you do: Learn your craft, be willing to experiment, know your subject, have something to say and your own way to say it, and practice, practice, practice. I guess there is no substitute for just working.”

Western art is a genre of subject matter that originated with interpretations of Eastern emigrés. Descendants of the Hudson River School and Golden Age of Illustration became pioneers of the Taos School, the rise of California Impressionism and the more recent variations of Western regionalism. Nautical art has connoisseurs every bit as zealous and discriminating as those scrutinizing depictions of cowboys and Indians.

Blossom may be only an itinerant Westerner but he has tens of thousands of miles and hours under his belt in the red rock deserts, inner mountain ranges and Pacific coastline. He has also spent countless hours prowling the Atlantic, but he does not compartmentalize one from the other.

“In fact, I view my maritime work as landscape with water and vessels,” he says. “In terms of light, near the water there is more moisture in the air, which can produce a luminous effect at times, but can also have a tendency to restrict visibility in the form of haze or fog, which grays color. I enjoy looking for interesting lighting effects and will try everything from close-value, high-key lighting to backlit, high-contrast pieces.”

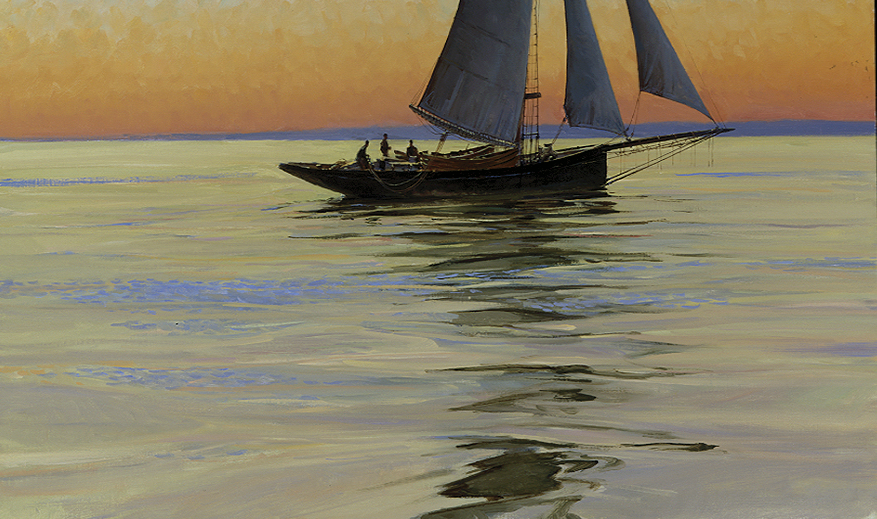

In Smuggling off San Diego, Brig BETSY, Sept., 1800, Blossom’s nocturne conveys the mystery of West Coast pirates. With the soothing and tonal Hauling Traps at Dawn, it could be lobstermen from any fishing village. And in Gloucester Sloop Bound for Home at Sunrise is a picture that would make Pyle or Winslow Homer proud.

It’s not only Blossom’s originals that are collected. Some 30 years ago, Greenwich Workshop published one of his nautical pieces as a print. Scott Usher, the company president and CEO, says that coastal dwellers up and down the Eastern Seaboard purchased the modestly priced reproduction, starting a relationship with Greenwich that has endured. The company also sells decorative reproductions of paintings by acclaimed narrative artists Howard Terpning and Mian Situ.

“I can say, without offending those other guys, that just about everybody recognizes that Chris Blossom creates scenes that grab your attention,” Usher says. “In terms of quality, he has a lot in common with the peerless draftsmanship of Terpning and Situ.”

For Blossom, he adds, it involves a coming together of tenacity and hard work, education background, luck “and then there’s this 15 percent factor of pure magic.”

The late wildlife artist Bob Kuhn, who similarly started as a Connecticut illustrator before relocating to Tucson, looked at Blossom’s work and said, as praise, that it reminded him of lumbering elephants or, in Blossom’s portrayals of sleeker watercraft, wild cats on the prowl.

Blossom knows how to convey the kinetic energy of a boat stalking the sea, being animate within a larger realm of motion, and yet translating fluidity onto a flat, stationary surface. He achieves the same atmospheric effects with clouds floating over landforms, casting shadows and the abstract shapes of reflected light.

“Ships, like animals, are not static, though of course ships are inanimate objects,” Blossom explains. “Sailors tend to be a superstitious lot and project that spirit onto their vessels so that they become animate, at least to them. I try to infuse the paintings with that potential for motion.”

How does he choose his nautical narratives? Perhaps surprisingly, he says, “They are usually the last part of my painting planning. My painting ideas most often come from something I’ve seen on the water, usually a small thing like some particular kind of light, or the way a wave breaks.”

He adds, “I’m interested in historical accuracy, but I’m more interested in portraying the simple moment rather than the grand historical event. Whether it’s light, or an interesting abstract design, or a mood that I want to convey, once I have developed the picture idea and have a composition that does what I want it to, then I can fit almost any vessel to fit the idea, but it all starts with that small idea.”

Dwelling in the moment, seeking adventure, often serve as catalysts. In 1998, Blossom and his wife checked their young kids out of school and spent several months sailing around the Bahamas and then skirting northward toward Maine. It was important for familial bonding, but the sojourn, also intended to refresh Blossom’s visual memory, did something else: It affected his palette.

“When I look back on the trip, I can see that it changed my color sense. I became more comfortable with color; it’s hard not to when confronted by the brilliance of the light and color down south. Different for me in that I was so used to the subtle grays and muted colors of the Northeast,” he says.

“That time on the water has served me well over the last 10 years in terms of picture ideas as well, though I am beginning to feel the need to get out there again.”

What’s clear-eyed is his vision of the West. “Unlike most artists painting outdoors, he has the ability to finish a work on the spot,” says Bill Rey, owner of Claggett/ Rey Gallery in Vail, Colorado, that represents Blossom’s work. “Many plein air painters love to throw paint and color around, but they can’t bring closure to the painting.”

Rey says that he applauds Blossom’s eye and composition. “He has a masculine approach to his landscapes, whether they involve the natural geological wonders of Zion National Park, a horse pack scene or fly fishing in the mountains,” he explains. “But subject is really secondary. He could paint an old Volkswagen bug and make you want to have it on your wall.”

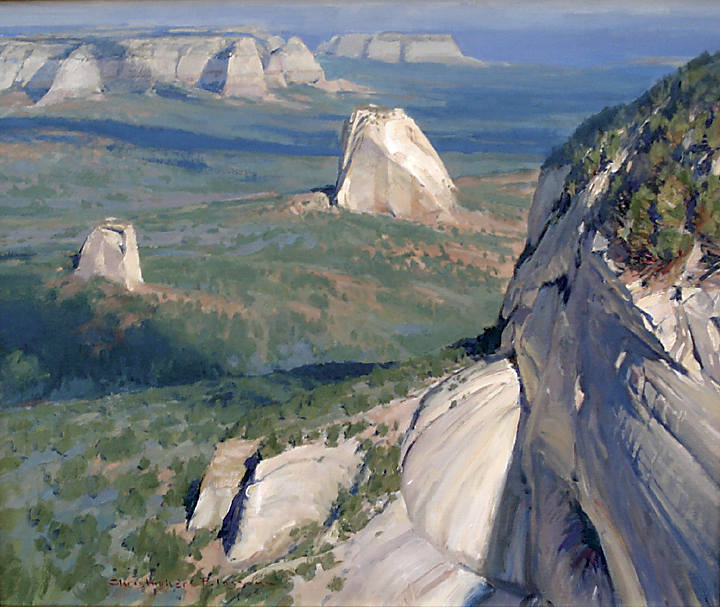

View From The Mesa, now at Claggett/Rey, is a wonderfully designed portrayal of a massive Southwestern valley filled with jutting, monolithic towers of stone. His alpine lake scenes are as fine as those of any artists who have been in the West all their lives.

“I have always been drawn to the water. I like being around it, and I feel certain that if I wasn’t painting I would probably be doing something related to being on the water,” he says. “The age of sail has obviously caught my attention. I think, perhaps, because it was a time when our technological development was tied more to the idea of working in conjunction with nature as opposed to overcoming it. I explore my curiosity through my paintings.”

Blossom likes to give his viewers a haven where they can eddy out of the rat race and dwell in solace. “I want to paint a specific kind of moment that the viewer can identify with, either because they can recognize a particular kind of light, or the mood, that reminds them of something they have seen in nature before. If I can make that connection, then the painting becomes more real.”

“There are a lot of craftsmen out there, really good dedicated people who paint well, but not so many who are inspired and can take what they know and turn it into something that transcends a nice picture,” Chmiel says. “Chris is one of those guys.”

A Coloradan today, Chmiel was raised in southern California, where he worked on fishing boats, and says the maritime history of the West is a motif that has gone profoundly underexplored.

“Most marine artists I’ve seen paint the cosmetic surface,” he says. “They don’t get the feeling of the planet rotating under this enormous deep layer of fluid. Chris presents the mass of the whole ocean. He could paint the cliché, but he doesn’t do it. He gets to the guts of the thing. What translates in all his work is a knowing. You only get it when you understand the power of being alive.”

Todd Wilkinson has been a journalist for 25 years, writing about the environment, arts and culture on assignments that have taken him around the world. He lives in Bozeman, Montana, and is author of a forthcoming biography about media mogul turned bison rancher and eco-humanitarian Ted Turner.

- “Hauling Traps at Dawn ” | Oil on Linen | 12 x 30 inches

- “Early Morning, Gloucester ” | Oil on Linen | 10 x 12 inches

- “View from the Mesa” | Oil on Linen | 20 x 24 inches

- “Becalmed” | Oil on Linen | 18 x 30 inches

_0274.png)

No Comments