29 Dec Authenticity in Detail

A PAINTING HAUNTS MORGAN WEISTLING. IT'S NOT ON CANVAS. It’s pacing back and forth across his mind and has been there for 10 years. “I am frightened to bring it to the front because I know how incredibly painful it will be to pull it into reality, but I know that one day I must,” says Weistling in his Canyon Country studio, just north of Los Angeles.

The scene is typical Weistling (pronounced Whystling) — an extremely powerful and moving portrayal of early Americana, in this case, the Civil War. It’s not an epic scene. “I don’t do epics. I do everyday people and their lives,” says Weistling.

In his mind, there is a young girl, about 16 years old, a seamstress who is patching a soldier’s uniform. Behind him, other soldiers are waiting to get rips and tears in their uniforms fixed. It’s a very rural background and there may be some other girls around. The whole setting is a wartime battlefield scene and there is a stark contrast between the girl, who has remained pristine, and the soldiers, who are covered in the grime of war.

“I hang out with Civil War re-enactors and I go to their events looking for the elements of this painting. I see it clearly in my mind,” says Weistling. “To me, it is epic, but I like to keep it simple.”

“I know some of my collectors would like me to do museum-style paintings of great historical moments — Kit Carson riding at the head of the wagon train,” says Weistling. “But my eye is always drawn to the little girl in the fourth wagon who is busy making soap to help everyday life get along.”

Some artists set out with a general idea of what they are going to paint and adjust it along the way. Not so with Weistling. A stickler for authenticity in every detail, he must know exactly what elements will be included in the finished work, down to the small embroidered fringe on the cuff of each little girl’s dress.

“The research can be excruciating, extremely time consuming and frustrating as I search to be faithful to our forebears,” says Weistling. But to focus on the detail and precision is to miss what Weistling is seeing. Life is made up of small snapshots, and through a masterful use of light, Weistling is able to capture the very essence of each moment. Youthful vitality pours from First Dance, 1884, winner of the Artist’s Choice Award and the Patron’s Choice Award at the 2008 Masters of the American West at the Autry National Center of the American West Museum in Glendale, California.

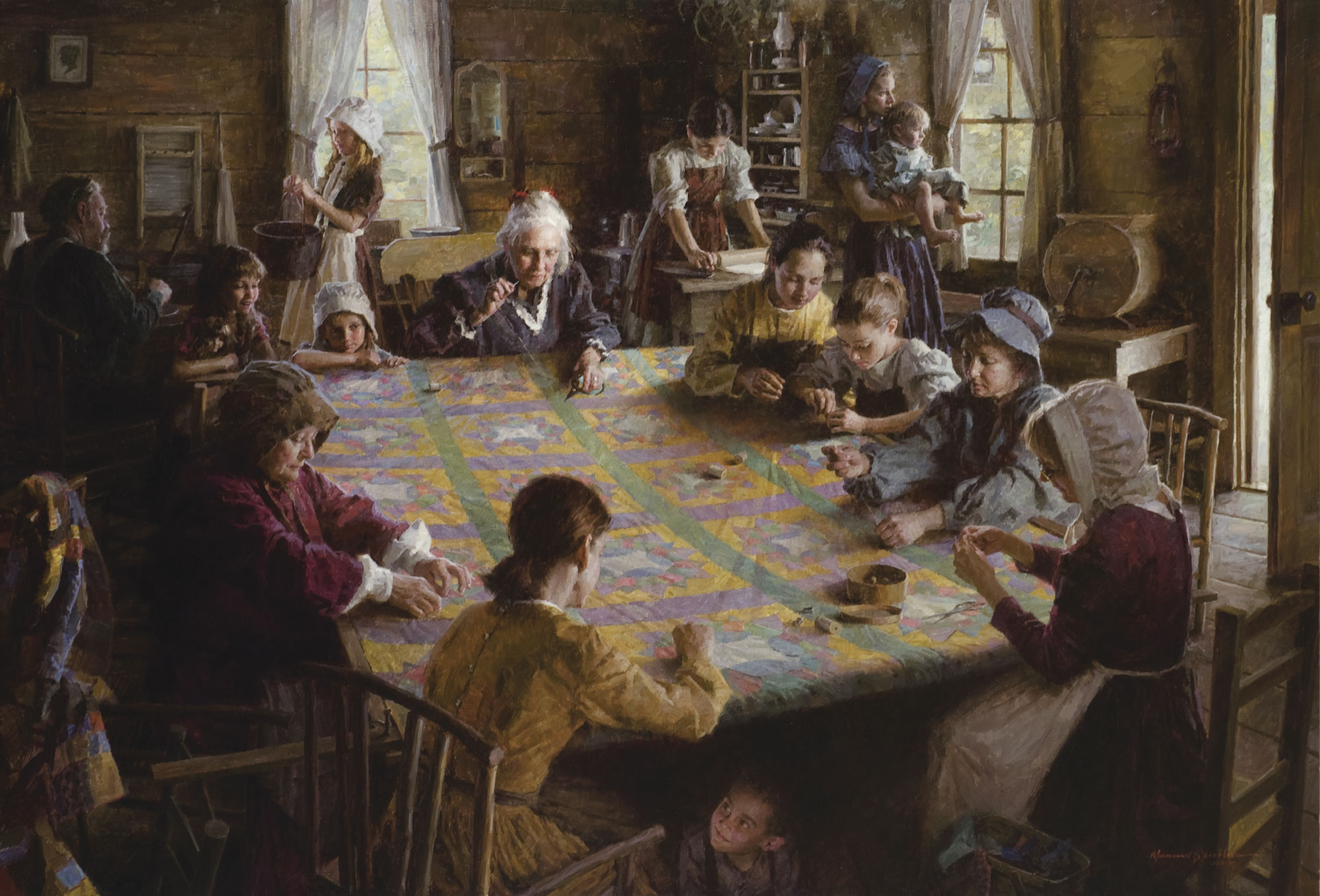

Similarly, The Quilting Bee, winner of the same two awards at the Autry show in 2007 (a rare achievement), hauntingly encapsulates the industriousness of 19th-century women; and Indian Stories, winner of the 2008 Purchase Award at the Prix de West in Oklahoma City, reminds Weistling of the stories told to him by his grandmother, who came West in a covered wagon and listened each night to the kind of storyteller immortalized in the painting. And there is the seemingly endless array of portraits from old men to young children, each capturing a moment of intimacy between the subject and the viewer. It is a remarkable body of work for a man, only 46 years old, who spent 14 years as a commercial artist before venturing into fine art.

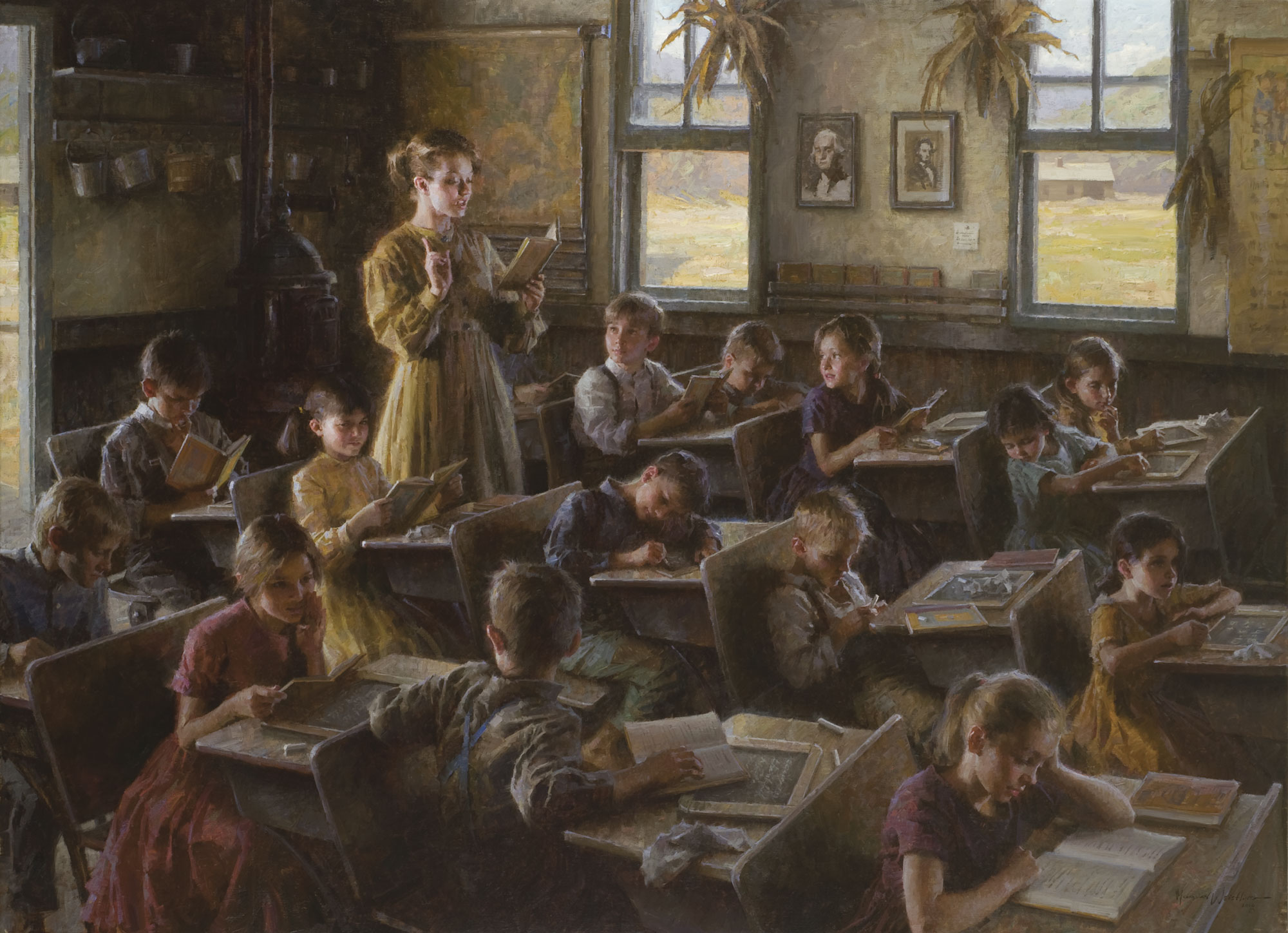

Weistling has just completed what will be a featured work for the 2010 Masters show at the Autry next month: an 1890s schoolroom. “It took me weeks to get up the nerve to dive into this thing. I said, ‘OK, I have to find a schoolhouse from about 1890 and put 14 children in there, a teacher, desks, wall decorations and all be in period!’ ” says Weistling. “lt’s not like I take a camera shot and say, ‘Oh, I will do a painting of that.’ All this must first be created inside my own head and then researched for accuracy — that’s what’s scary. I sometimes want to use old, beaten-up stuff as props, but then remember that I have to show them before they sat around 100 years getting old. I am seeking to paint a truth that no longer exists, but make it truthful — it’s challenging.”

Destiny decreed that Weistling would be an artist. His parents met at art school in the Burbank area of Los Angeles, “but they eloped and started a family so my father was never able to pursue his art dream. Instead, he started a gardening and landscaping business to support his family, but after 40 years broke his back and became a locksmith until he died five years ago.”

Both parents (his mother still paints “beautifully decorated dinner plates”) poured their love of art into a young son who arrived late in their lives. “They told me that they would sit me on a couch with a piece of art and I would be content to look at it for hours. At 19 months, my father had me sitting next to him, drawing. He loved comic strips at the time when comic strip artists were king and I would copy whatever he drew.

“He kept a diary every day from age 14 until the day he died at 83. I have them all. They are brief and to the point. I checked the day I was born to see if the earth moved: It says ‘Pat had a boy today.’ That’s it! Pearl Harbor day records ‘Japs attacked Pearl Harbor, went to movie.’ The next day — ‘I enlisted.’ ” (Weistling Sr. became a navigator in the Army Air Corps, was shot down on his first mission in a B-17 bomber and spent a year in the Stalag 1 prison camp in Germany before being released in 1945.)

“I also have every one of those drawings we did together — every single one, and we did them each night after his work, along with every sketch I have ever done on all my paintings,” says Weistling. “I have been bred to cherish history,” he says, adding quietly, “including my own.”

However, Morgan does not get the only family spotlight at this year’s Autry show. His wife, Jo Ann (they also met in art school), who paints under the name of J. Peralta in honor of her grandmother, will have a piece in the same prestigious show. She has drawn casually all her life but with no thought of art as a career. Jo Ann was a travel agent in the early 1980s when another agent needed a drawing of two football players for a flyer.

“He was a graphic artist and when he saw my flyer, he suggested I check the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. They said I needed a portfolio of 12 pieces and I had nothing to show them. I presented the portfolio two weeks later and they gave me a full four-year scholarship,” says Jo Ann, whose paintings focus on working people of Spanish heritage, like her grandmother. Incidentally, she hates to travel.

And right behind the talented mother and father is 14-year-old Brittany, already showing great promise in art, sculpture and music. She recently sold five pieces of her work to buy a laptop computer and Morgan, who still has all his earlier pieces, says, “I compare my work at age 14 with hers — she’s better.” Brittany, who has been drawing since she was two years old, says that when she sees the enormous effort and work her father puts into each piece, “I might check out one of my other talents. It’s pretty intimidating to have two such incredibly gifted parents.”

Weistling’s own career has been a series of quantum leaps. He was selling painting materials in an art store at age 19, and showed his work to a top Hollywood illustrator who was buying supplies. The next day he was employed by a leading film company and worked for every big film producer in Los Angeles for more than a decade.

Encouraged by a friend, fellow artist Julio Pro, Weistling went to Scottsdale with a few unframed pieces he did while still doing movie posters, “to see what happens,” as Pro put it then. “We started at the top — Trailside Galleries,” says Weistling, “and co-owner Maryvonne Leshe asked if I would sign for them to represent me right then. And, of course, I did.”

“I remember,” Weistling recalls, “Maryvonne commented on the hands and feet in my paintings. She said most people hid them because they are hard to do, but I did them very well.”

“That is very true, hands and feet are a defining feature of top artists,” says John Geraghty, noted art collector and a founding member of the Autry show. “You will see the same thing in Howard Terpning’s work — his hands and feet are exquisite, as are those of Mian Situ. In fact, in my mind,” Geraghty adds, “what Howard Terpning is to the Plains Indians, and Mian Situ is to the Chinese-American experience in this country, that is what Morgan Weistling is to the Americana of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.”

Praise does not come much higher than that.

- Indian Stories | Oil | 40 x 46 inches

- First Dance, 1884 America | Oil | 30 x 50 inches

- The Quilting Bee, 19th Century Americana | Oil | 44 x 64 inches

- Morgan Weistling

- Vineyard Girl | Jo Ann Peralta | Oil | 45x 26 inches

- Grizzly | Brittany Weistling | Oil on Canvas Board | 9 x 12 inches

- Brittany Weistling

- String Beans | Morgan Weistling | Oil | 30 x 26 inches

- Jo Ann Peralta

No Comments