30 May Artistic Evolution: A Daughter's Perspective

ART IS A REFLECTION OF THE ENVIRONMENT in which it is produced,” my father has said. Whether an observation or more of a credo, it is a belief by which he has lived. My father, artist Theodore Waddell, is, and always has been, inspired by the varied landscape in which he lives. These days his environment shifts as he splits his time between Sun Valley, Idaho, and Sheridan, Montana. His passion for and keen sense of both places is inextricable from the work that he produces.

“Idaho has different, close vistas because of the mountains, also a haze at times that can’t be explained and is difficult to paint. Montana has the broad open high plains and crisp air that changes the light due to less humidity, making it hard to paint at times. There is great benefit from experiencing both environments. I love both places.” His connection to place goes back as far as I can remember. Reflecting upon the geographic changes of Dad’s studio, and our life together, I have a new perspective on my father’s work and how his style has developed.

Dad’s studio has always been at the center of his life but with each physical and geographic change there is a shift in his artwork. The first studio I remember well was on our isolated farm in south central Montana. A converted car garage with a large adjoining auto shop, the space was necessitated by large farm equipment and inevitable repairs. I remember the small studio being very cold and I know my father painted in his Carhartt jacket, winter overalls and wool hat. The only heat came from the wood-burning pot-bellied stove.

The small horizontal windows of the garage door faced east across the plains toward Adam Thompson’s buildings two miles away. Each day Dad welcomed the rising sun. The early morning sunrise paintings of those years illustrated the stark, flat horizon line of the dry-land farm. Sky was the artist’s subject and the composition contrasted the dark rich earth beneath the pink sunrise above. Learning from the French Impressionists, Dad emphasized light and its changing qualities. The way my father painted the morning twilight in those years was spiritual for artist and viewer alike, I believe. As the prayerful wake to mouth the words of hope, so too my father arose in the pre-dawn darkness, fervent to capture the dawn. The farmer’s day that followed the painter’s reverie was filled with hard physical labor. It was rare that Dad was able to devote an entire day to painting. The joy of my father’s life today is that his days are filled with the pleasure of painting.

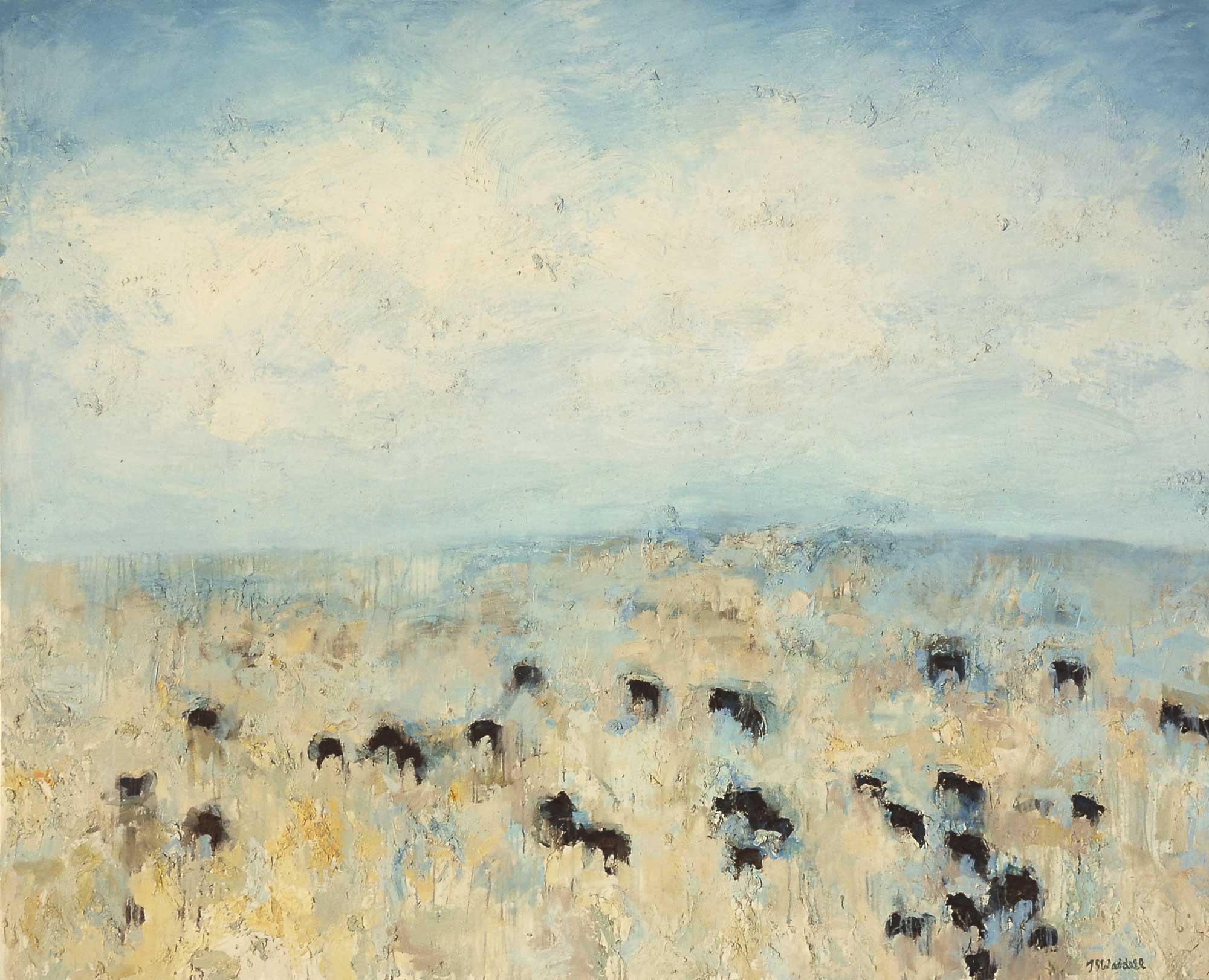

In the 1980s, our family was responsible for more than 200 head of cattle on the remote Montana farm and those animals were the predominant subjects of my father’s work. Dad portrayed the black Angus cows as singular subjects with individual characteristics or abstracted as large amorphous groups. As the agricultural demands waned in the winter Dad painted more frequently, as the many snow white compositions from this period can attest. Inspired by the anti-figurative aesthetic of the Abstract Expressionists, the white canvas is dotted with splashes of black paint. The subject is a winter whiteout with black cattle scattered throughout, something that can only be ascertained on a subconscious level and at a distance.

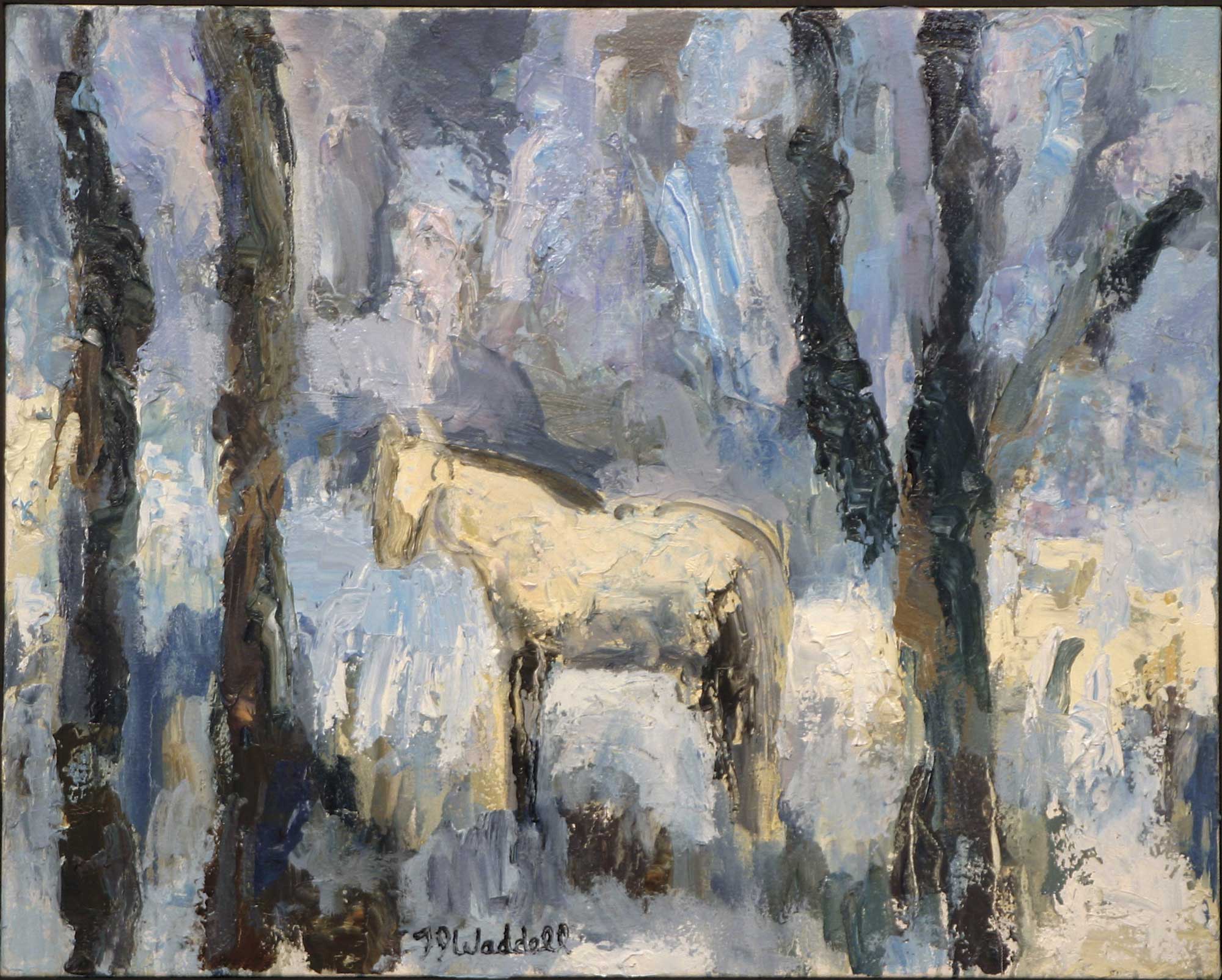

Throughout my father’s life, consideration of the studio was the most important aspect of any real estate transactions. The early 1990s studio in Ryegate, Montana, was twice the size of its predecessor and thankfully much warmer. The palette, which was actually a table, also grew in size and became mobile when casters were attached. A running length of wall provided a way for Dad to contemplate larger scale works in progress. With the location, and scale, the subjects of my father’s work also changed. Located along the Musselshell River, the windows of the studio faced the gentle, meandering water which made its way through the property. The river, the trees and our only horse were some of his favorite subjects. These years were prolific for my father because the ranch was smaller and we owned fewer cattle. Less time working the land meant more time painting it.

Like the symbolic nature of the river water, my father transitioned as he moved his studio to Manhattan, Montana, in the late 1990s. This studio was unique in that it was the only one physically attached to the house. Dad looked east across the pastures full of cows, to Ross Peak in the Bridger Mountains and south to a portion of the Spanish Peaks range. What most people fantasize about the imagery of Montana is what my father painted — “the last best place.” Dad transitioned from Ryegate through Manhattan and on to Idaho, without ever putting down his brush.

A visit to Dad’s studio in Sun Valley, Idaho, today is to experience the chief subject of his paintings — horses. No longer does my father have to divide his studio to accommodate farm equipment. Now, he willingly shares his space with the physical presence of the large, graceful animals. Dad paints portraits of his horses much the way he did cows in the 1980s.

Dad’s newest studio in Sheridan, Montana, is a 100-year-old house and horse barn converted into a two-room studio, completely stocked with paint, paper and canvas. To the south, the studio looks out toward the Ruby River drainage and Ruby Mountains. North are the Tobacco Root Mountains. Dad can see both from the studio. “I hear cows mooing when I get up, deer in the yard sometimes and sandhill cranes talking in the summer,” he says. Lately, my father has been painting buffalo because Ted Turner has two ranches nearby, stocked with buffalo.

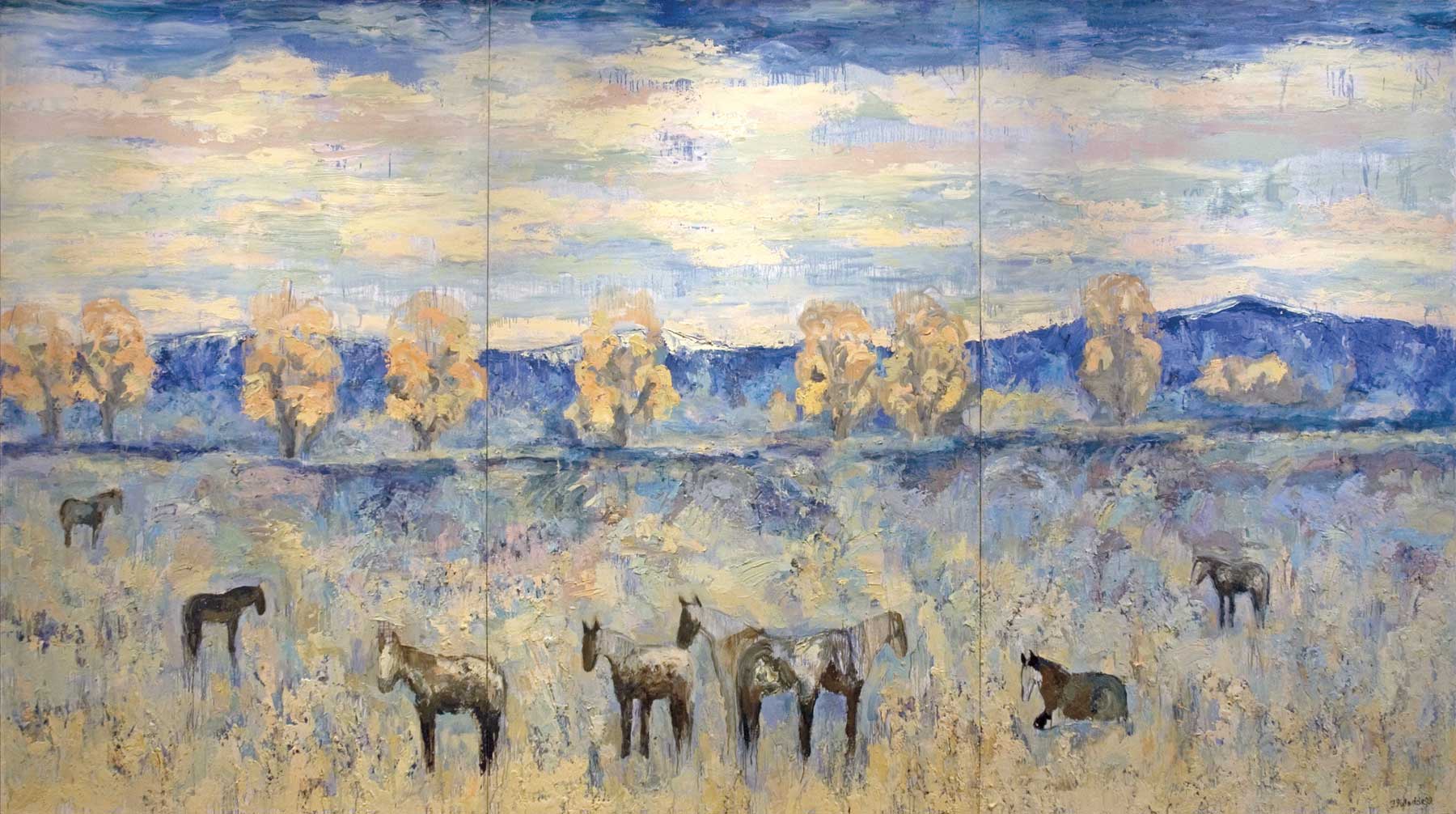

Dad’s portable palette is a garden cart on wheels and with the mobility it allows, he can paint outside, or en plein air. As an artist, he has always been moved by the landscape in which he stands. And, while I know Dad doesn’t consider himself a landscape artist, he most certainly produces some of the more awe-inspiring works of the genre. With the freedom to paint on any scale, my father has recently painted the largest canvases of his career and the studio easily accommodates them. The most recent triptychs are as large as 10 feet by 18 feet and the subjects are primarily landscapes where distance and scale are determined by the cattle or horses which populate the scene.

Symbolically, the walls of the studio have fallen away and there is very little to separate Dad from his subjects, whether they are horses, cows, buffalo, sheep or the landscape itself. Immersed and inspired by his environment, my father’s take on Western art is impressionistic, modern, abstract, emotional and subconscious. In many respects unable to be categorized, my father’s portrait of his environment encompasses beauty and serenity. His depiction is of a West I have always loved.

Shanna Shelby is the curator for a large private fine art collection in Denver, Colorado. She recently curated three exhibitions: Designing Women of Post-War Britain: Their Art and the Modern Interior; Hungarian Masterworks: from Impressionism to Modernism; and Styling the Modern: Fine Art Meets Fashion, all of which are traveling across the country.

- “Sunshine #2” | Oil | 24 x 30 inches | 2010

- “Lost River Angus” | Oil | 78 x 96 inches | 2002

- Waddell with a few of the family’s equine members

- “Monida Angus #9” | Oil | 60 x 60 inches | 2010

- “Monida Angus #10” | Oil | 66 x 72 inches | 2010

No Comments