30 May The Evolution of Continuity

BORN IN 1946, CHARLES ARNOLDI HAS BEEN MAKING ART FOR MORE THAN 40 YEARS. His life, it seems, has been an uninterrupted and utterly organic exploration of material, shape, pattern and color. Described — perhaps branded — as “a natural,” Arnoldi has transitioned spontaneously and constantly from one medium to the next.

In his new monograph, Charles Arnoldi:1972-2008, a provocative and visually stunning book published by Radius Books, the artist openly and insightfully dialogues with top art experts on the course of his life and prolific career, which includes collections at some of the world’s most renowned museums: the Museum of Modern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Guggenheim, Bilbao, Spain.

Sticks 1

… In 1969, I made the first stick piece. … The inspiration for these pieces came from a trip up to Malibu with my friend, Jim Ganzer, after a fire. We had gone to steal fruit from a secret orchard that had been exposed to the highway. We were standing in the middle of the orchard looking out at the Eucalyptus trees around the perimeter. There were no leaves; all that was left was the blackened tree branches. I thought they looked like beautiful hand-drawn charcoal lines, with the sky as the backdrop. So instead of taking oranges and avocados, I took a bunch of tree branches back to my studio.

Chainsaw

Well, yes these [block paintings] did transition into the larger Chainsaw paintings. Of course, the minute I do something on one scale I think, wouldn’t it be great to do some big ones? In my mind I had the idea that I should get a block about 12 inches thick and maybe 8 by 8 feet. So after many calls about how to find a piece of wood that big, we finally got through to somebody and they said they could do that, but it would mean they would have to go way deep in the forest, cut down a tree that was like a thousand years old, cut the slabs out of it, helicopter it out, and they would be happy to deliver them at about something like five or ten thousand dollars a slab. I thought, “I can’t do that!” I decided I could make them out of plywood. I bought 48 sheets of plywood, several gallons of glue and glued them together piece by piece. I ended up with a chunk of wood that was 8 feet by 8 feet and 18 inches thick that was glued to the studio floor and we couldn’t lift it! Eventually I realized I could make them thinner and that led to the Chainsaw paintings. … [Arnold] Schwarzenegger came by one day and said, “I’d love to have that painting.” I told him it wasn’t for sale, and he said “I want it; how much do you want for it?” I told him I wanted $15 million for it (his recent salary for a film). He said, “You can’t have that,” and laughed. He eventually bought the painting — but for less than $15 million, of course.

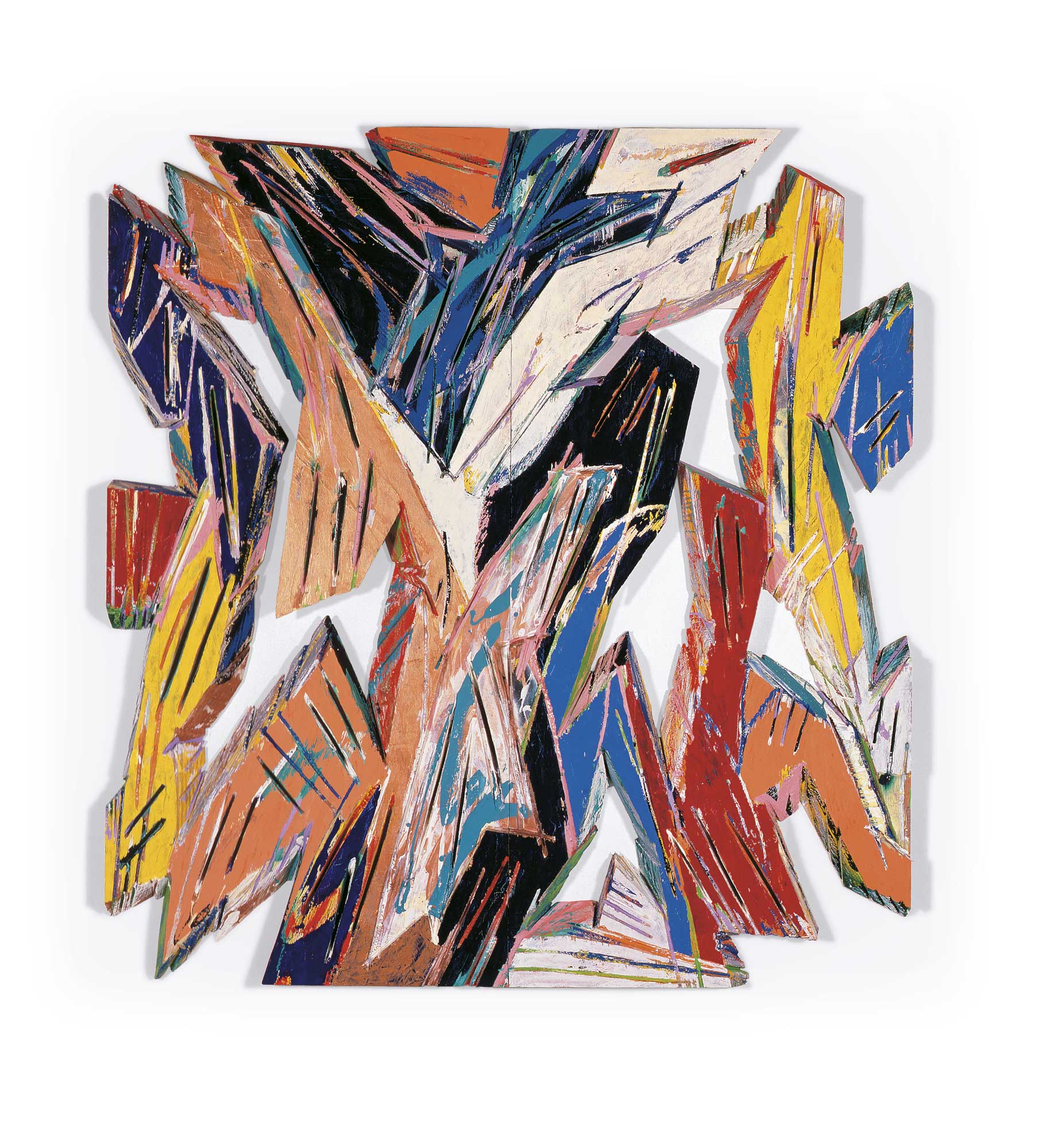

Gestural

In 1988, my first child was born. My mother and brother both died within six months of each other and it made me stop and reflect. My life had gotten rather complicated. I had bought the foundry where I was casting bronze; I had way too many telephone numbers, too many assistants and too much stuff. So I decided to quit making Chainsaw paintings, or anything that took assistants, and I just started making paintings on canvas. I felt like I had built a personal linear vocabulary, but I really sort of just jumped off a cliff without a parachute. These are just about brush strokes.

Hawaii

In 1990 we built a house on Kauai. At the time I was making black-and-white oil paintings, but when I got to the island, I didn’t want to paint with oils. It was just too toxic. So I was literally sitting in paradise and I’m looking at plants there that are chartreuse on one side and violet on the other side. Everything was so beautiful, so I thought, “Who gives a shit? Why don’t I make some pretty paintings?” That’s when I started using acrylic paint. With acrylic paint you can literally pour it, pee on it, walk on it — do whatever to it because it’s plastic. I think that 99% of acrylic paintings look like crap because the medium is not good. It looks great when you’re painting with it, but when it dries it loses the richness. As a personal challenge I wanted to see if I could make a really good acrylic painting, whatever that means. So I kept working on these and they became more and more layered. In my mind, Spitfire is a really good painting, but I realize they are pretty paintings, and to say it is beautiful is even worse.

Medals

The pieces on metal that we’re looking at came from the process of making monoprints. We start with an aluminum litho plate painted with oil paint. It goes through a hydraulic press that puts out 700 tons of pressure. After painting and printing on the plates over and over, like eight to ten times, the plates become more absorbent than the paper and therefore won’t transfer anymore. The used plates themselves were really beautiful objects, so I saved them and accumulated a hundred or so. They were so beautiful, I decided to make pieces out of them. I called them “medals” because they’re kind of a reward for going through the agony of printmaking.

Windows

Most of my recent work is on canvas. I haven’t given up the Medal pieces, … but I’m also doing some Window paintings. The first one I painted — or what I consider to be the first Window painting — was made right after Agnes Martin died and I titled it Agnes. I had these different sized canvases, and when I arranged them in a certain way, it left a little hole in the middle, a window. I liked this window, especially as a metaphor, and so I left it. … It is amazing. I do see all this stuff as interconnected. Just because these Window paintings are new in some ways it becomes clear after years that you always make similar decisions as an artist, and there is a continuity. You can’t avoid yourself. There is a similarity in the work whether it’s a Stick painting, … or one of these.

- “Frostbite”, 1987, Acrylic on Plywood, 90 x 84 x 3 inches

- “Spitfire”, 1995, Acrylic on canvas, 104 x 96 inches

- “Untitled”, 2005, oil on copper, 14.25 x 11 inches

- “Brain Freez”, 20076, Acrylic on Canvas, 88 x 82.5 inches

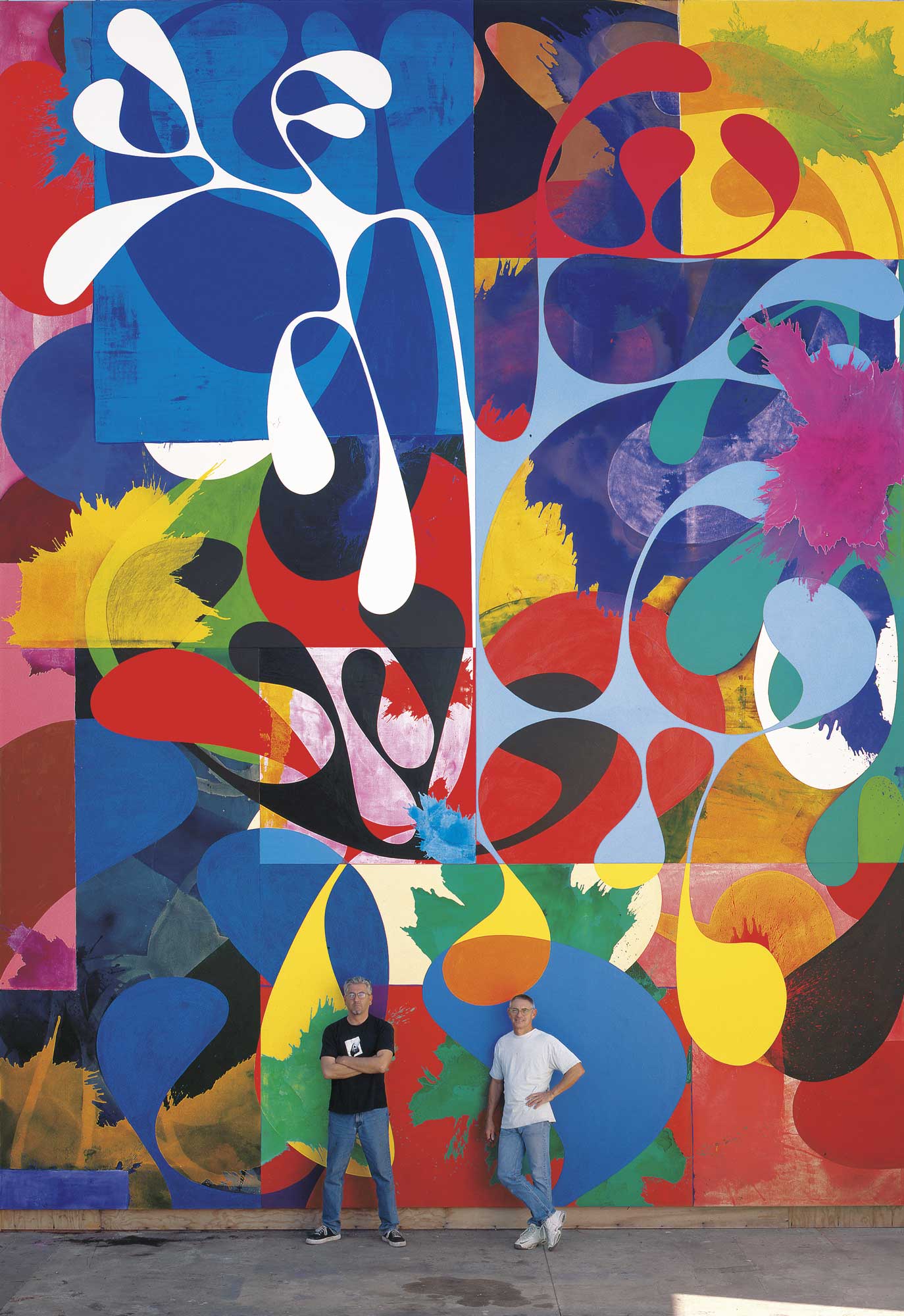

- Standing in front of CORE, David Lloyd, left, and Charles Arnoldi

- Charles Arnoldi in his Venice, California studio.

- “Untitled”, 1970, Latex, String, and Sticks, 26 x 36 x 2 inches

No Comments